Top tips for super sandcastles: explore the weird world of sand

Building sandcastles is one of the little pleasures of a holiday on the beach, but what do you really know about the science of these structures? Ian Randall grabs his bucket and spade to explore the weird world of sand science

A peerless edifice rises into a brilliant blue sky. Around a central, vaguely pyramidal tower, dozens of spires and turrets of assorted shapes and designs jut out between battlements and buttresses. Around the base runs a fortified wall, behind which a watchful dragon emerges from a body of water, while a lighthouse beams down from one side of the imposing structure.

This isn’t the design of a new Physics World head office [alas! – ed.], but that of a colossal sculpture that recently broke the Guinness World Record for the tallest sandcastle ever built. Crafted from 4860 tonnes of sand, spanning 32 m wide and rising to a height of 21.16 m, the castle (see photo above) was constructed by Dutch artist Wilfred Stijer and his 30-strong team of sculptors. It was built, with the aid of an elaborate wooden scaffold, in July 2021 in the Danish seaside village of Blokhus, in North Jutland. Thanks to a layer of glue applied to its surface after completion, the super sandcastle is expected to remain on display for visitors to enjoy until February or March next year, when the next heavy frost will set in.

But working with sand isn’t as easy as it looks. Before Stijer and his team’s success, the world’s tallest sandcastle was a 17.65 m tall structure built in the German seaside resort of Binz by another Dutch sand-sculptor, Thomas van den Dungen. No stranger to pushing sand to its limits, he had previously helped to create the world’s longest sand sculpture (27.3 km) and the largest number of sandcastles built in one hour (2230).

However, Van den Dungen’s previous two attempts to break the tallest-sandcastle record failed after one edifice collapsed days before completion, and the other was foiled by a flight of protected shore swallows that had nested on the construction site. None of us are likely to build anything as ambitious when we’re holidaying on the beach, but is there anything that science can tell us about how to make the perfect sandcastle?

Slippery when wet

A good place to start is with Matthew Bennett, an environmental scientist at the University of Bournemouth in the UK, who in 2004 was commissioned by Teletext Holidays to identify the UK’s best beaches for making sandcastles. Different beaches have different types of sand, so his job was to find out which has the best material to work with.

Arming his students with buckets and spades, Bennett sent them to the 10 most popular beaches in the UK at the time, with instructions to collect samples of sand from each. Once they had brought the material back to the lab, his team dried the sand, poured it into beakers, added water and turned each full container upside down. “We then piled weights on each ‘lab-castle’ top and noted the total weight [it could sustain] before collapse,” Bennett explains.

The key to a strong sandcastle, the team found, was to mix one bucket of water to every eight buckets of sand. That 8:1 volume ratio, which was the same for all 10 locations tested, is in fact roughly the same composition found on real beaches around the point where the water comes nearest to the shore at high tide.

According to Bennett, this perfect ratio ensures that the water helps only to bind the sand, rather than act as a lubricant. Too much water and your structure will flow and collapse, which is what happens when sandcastles meet their natural predator, the tide. Too little, on the other hand, and the sand crumbles.

In fact, the strength of a pile of sand depends on two factors. The first is the structure of individual grains. Those that are more angular and irregular will lock together better than grains that have become rounded by virtue of having been transported a long way – a process that abrades them through the action of wind and waves. It’s why sand containing lots of microscopic, angular fragments of broken seashells is good for building strong sandcastles, Bennett explains. The other, more important, factor is the amount of water held between them, with smaller grains holding more water.

Bennett’s study led him to name Torquay in the south-west of England as Britain’s best place for sandcastles, thanks to what he calls “its delightful red sand”. Close in second is Bridlington in East Yorkshire, with Bournemouth, Great Yarmouth and Tenby all tying for third. “It was a simple but effective experiment,” Bennett recalls, explaining that he still uses the investigation as a fun way to engage people in geological concepts.

He admits, though, that any sand can, in principle, be used to make sandcastles – and that the selection of Torquay’s red sand as the “winner” of his 2004 study was in no small part down to its attractive aesthetic properties. It did help, however, that the sand in question originated more than 200 million years ago when Britain, which was then located in the interior of the supercontinent Pangaea, was part of a desert that outsized the Sahara. Torquay’s sand therefore has lots of fine grains, which Bennett says boosts its cohesive properties.

Bridges, not too far

For a physicist, a sandcastle is simply a structure made of a compacted granular material (sand) mixed with a liquid (water or seawater). But how does this water help sand grains to stick together? The answer lies in the surface tension of the films of water that form between the grains. Just as the surface of water in a test tube curves up at its edges due to adhesive forces between the glass and the liquid, so water forms tiny “capillary bridges” between sand grains. These bridges pull the grains towards each other, minimising the surface area between the water and air while increasing the surface area between water and the sand to which it is attracted.

Now, while an 8:1 ratio of sand to water might be the best for sculpting, it turns out that wet sand is still stable – i.e. acting as if it were a solid – over a wide range of water contents. There’s obviously something odd about the force that holds sand together, which is what inspired Stephan Herminghaus, a physicist at the Max Planck Institute for Dynamics and Self Organization in Göttingen, Germany, to take a close look at the phenomenon.

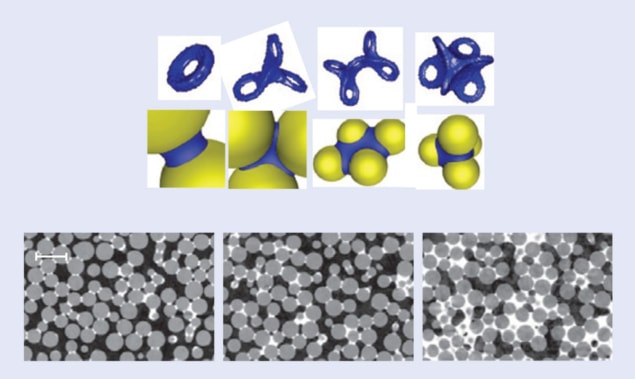

Rather than studying sand itself, he and his team turned to a model system made of wet, glass beads that were of similar size and shape to sand. Using X-ray microtomography – a technique that creates digital cross-sectional images of an object without damaging it – they were able to create 3D images of the beads and examine what happens as more water is added to the fake sand. The tiny capillary bridges, which initially link two separate grains, begin to get bigger and merge, forming increasingly complex structures that often look like a series of ring pulls from drinks cans stuck together (figure 1).

As the bridges grow, they come into greater surface contact with the grains, which increases the binding effect of the water thanks to its attraction to the sand grains. At the same time, however, the concave arch of the capillary bridge becomes less pronounced, reducing the negative pressure in the water As the negative pressure of the water is what draws the grains together, reducing it causes the grains to be drawn together less.

The two effects balance out, meaning that the simulated sand retains the same stickiness as more water is added to it. However, the rule was found to break down once the water occupied around 15% of the sand pile, or 35% of the total available pore space between the grains. Beyond that limit, the integrity of the pile began to weaken.

You don’t need much water to create big, tall sandcastles: small capillary bridges act like a glue between grains of sand

“The remarkable insensitivity of the mechanical properties [of the pile of sand] to the liquid content is due to the particular organization of the liquid in the pile into open structures,” the researchers note in their 2008 paper (Nature Materials 7 189). In other words, we now know why you don’t need much water to create big, tall sandcastles: it’s all down to the small capillary bridges, which act like a glue between grains.

A thumping good time

But is there a theoretical limit on how high you could build a sandcastle? That was a question that Daniel Bonn, a physicist at the University of Amsterdam in the Netherlands, set out to explore with his colleagues in 2012. They did this by pouring various amounts of wet sand into plastic cylinders of various diameters, before cutting away the mould and seeing how high the columns could be made before they collapsed.

The team found that columns give way when they buckle elastically under their own weight. Given this, the researchers determined that the maximum possible height of a sand column increases in proportion to the base radius of the column to the power 2/3. Do the maths and you’ll see that to build a column of sand twice as high as your friend, you need to make its radius √8 ≈ 2.8 times as big. From measurements of the elastic modulus of the wet sand, meanwhile, they concluded that the optimum strength is achieved at a liquid volume fraction of around 1%.

That figure differs from the ratio Bennett found in his bucket-and-spade study, which is perhaps not surprising given that real sandcastles tend not to be cylindrical, as in Bonn’s study, but often more conical. After all, a cone shape maximizes the stability of a sandcastle structure, as a modelling study published by Wenqiang Zhang from Zhengzhou University in China revealed last year (IOP Conf. Series: Earth and Environmental Science 514 022071).

Asked about practical tips for budding castle sculptors, Bonn says that compaction is key to stability. That’s why professional sandcastle builders usually use machines called “thumpers” that mechanically compact sand before it’s used by repeatedly stomping down on the ground. Compacting sand helps to shorten its capillary bridges, making the sand stronger.

What’s also useful is polydisperse sand containing a wide range of grain sizes. While we tend to think of sand as being made just of quartz, for geologists the term refers to any particles of worn rock ranging in size from 62.5 μm up to 2 mm. Expert castle builders in fact often favour sculpting with “river sand”, which has even finer clay particles ranging in size from 0.98 to 3.9μm. According to Bonn, river sand effectively puts small grains in the pockets between the large ones, thereby creating more capillary bridges and a stronger structure.

Clays, in other words, act as a “glue” between particles, even when there is little or no water. But if you haven’t got river sand, you can get a similar effect using seawater. As your sandcastle dries, salt crystals get deposited on the grains of sand, acting as a substitute glue. It’s one added advantage of building sandcastles at the seaside.

The sands of time

But even if there isn’t a nearby ocean to keep things wet, capillary bridges can form between sand grains as a result of vapour spontaneously condensing inside porous materials and between adjacent surfaces. Known as “capillary condensation”, this phenomenon can affect not only adhesion but also properties such as corrosion and friction in a wide variety of settings. In fact, the ancient Egyptians might even have benefited from making capillary bridges by pouring water onto sand in order to make it easier to pull heavy stonework across (see box).

Capillary condensation is usually described by an equation drawn up by the British physicist and mathematician William Thomson (later Lord Kelvin) in 1871. It links macroscopic properties such as pressure, curvature and surface tension, but the equation also holds at the microscopic scale. Indeed, it has proven to be surprisingly accurate even down to a scale of around 10 nm.

To investigate why this might be, a team led by the Nobel-prize-winning physicist Andre Geim at the University of Manchester recently fabricated the smallest capillaries possible. Some only one atom high, they were created from layers of atom-thin mica and graphite, separated by narrow strips of graphene that served as spacers. Geim and his team found that these tiny capillaries can accommodate only a single layer of water molecules within them (Nature 588 250).

Studying condensation in these capillaries, the team realized that the Kelvin equation remains an excellent description even at the molecular scale – even though at these dimensions, water changes its properties as its structure becomes more discrete and layered. “This came as a big surprise. I expected a complete breakdown of conventional physics,” says lead author Qian Yang. “But the old equation turned out to work well.”

According to the team, however, the qualitative agreement between the equation and reality is also fortuitous. Capillary condensation under ambient humidities creates pressures of around 1000 bars – more than found at the bottom of Earth’s deepest oceans. This pressure may hold the grains in a sandcastle together, but it also fractionally deforms the tiny capillaries in the researchers’ experiments, counteracting the altered properties of water at the molecular scale.

“Good theory often works beyond its applicability limits,” admits Geim. “Lord Kelvin was a remarkable scientist, making many discoveries but even he would surely be surprised to find that his theory – originally observed in millimetre-sized tubes – holds even at the one-atom scale. In fact, in his seminal paper Kelvin commented on exactly this impossibility. So our work has proved him both right and wrong, at the same time.”

Water like an Egyptian

If building sandcastles doesn’t satisfy your construction itch, it turns out that sand and water can be used to help make far more elaborate structures. Writing in a paper published in 2014 (Phys. Rev. Lett. 112 175502), a team led by Daniel Bonn – a granular physicist from the University of Amsterdam – argued that the ancient Egyptians used water to harden desert sand. This tougher stuff allowed the Egyptians to move sledges bearing heavy stones more easily about when constructing pyramids and other colossal monuments.

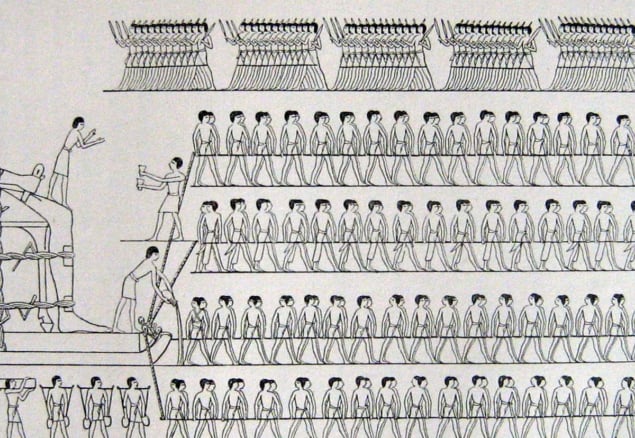

The inspiration for this notion came from a roughly 3900-year-old mural that once adorned a wall in the tomb of Djehutihotep, one of the most influential nomarchs (or provincial governors) in Egypt’s Middle Kingdom, which ran from about 2050 to 1780 BCE. The decoration depicted a giant colossus of Djehutihotep – the height of four men – being pulled on a sledge across the desert by 172 workers (pictured above).

What’s interesting is that the figure standing at the front of the sledge in the mural is pouring water on the sand over which the giant statue is soon to be hauled, while two other slaves replenish his supply. Egyptologists had long dismissed this curious action as a ritual, but Bonn and colleagues experimentally demonstrated that adding a certain amount of water to sand stiffens it by forming microscopic “capillary bridges” (see main text).

These bridges lower the friction coefficient of the sand, while also stopping sand from piling up in front of the sledge or letting it sink into the sand. Specifically, the team found that the coefficient of dynamic friction halves when the water content of the sand reaches around 5%. Anything more, however, and the friction rises, even surpassing the value for dry sand at a 10% water content.

It gets everywhere

Examining the physics of sand and the capillary forces that hold it together is useful for more than just building the best sandcastle. For example, the imaging techniques developed by Herminghaus and his team to study glass beads can be applied to grain–liquid–air interfaces more broadly. That work could therefore yield practical applications away from the seaside – from stopping powders clumping up to improving our ability to anticipate and prevent landslides.

Nailing down the mechanical properties of wet sand can also inform construction efforts. After all, most roads, railways, houses and buildings are built on sandy soils, but these need to be stable if such structures are to survive. Water can reinforce sand piles, which helps them become more stable, but it can also be a danger in reducing compaction.

As any civil engineer knows, building on un-compacted sand risks “quicksand”, a builder’s nightmare. Consisting of loose sand saturated with water, quicksand can initially appear solid. But being a non-Newtonian fluid, the quicksand liquefies when agitated, for example through a ground tremor. It forms a suspension and loses its viscosity, allowing objects to sink into the sand.

That’s a particular problem in the Netherlands, where Bonn is based, which has lots of quicksand on land reclaimed from the sea using dikes. Known as “polder”, this land cannot be built on immediately, forcing builders to have to wait several years for the sand to compact before starting construction. “If it is not compacted,” says Bonn, “you can sink away and get stuck in it.”

The perfect mix

So before you hit the beach, let’s recap. For a truly breath-taking sandcastle, select a location with a decent amount of finer-sized sand. Take wet sand from around the high-tide mark, which will give you the ideal 8:1 ratio of sand to water. Compact your material to increase stability. If you want a tall tower, aim for a wide base and a conical shape. Then simply unleash your creativity. You’ll have a masterpiece on your hands…until your structure is, inevitably, washed away by the incoming tide.