BY STEPHEN F. EISENMAN

COUNTERPUNCH

MARCH 11, 2022

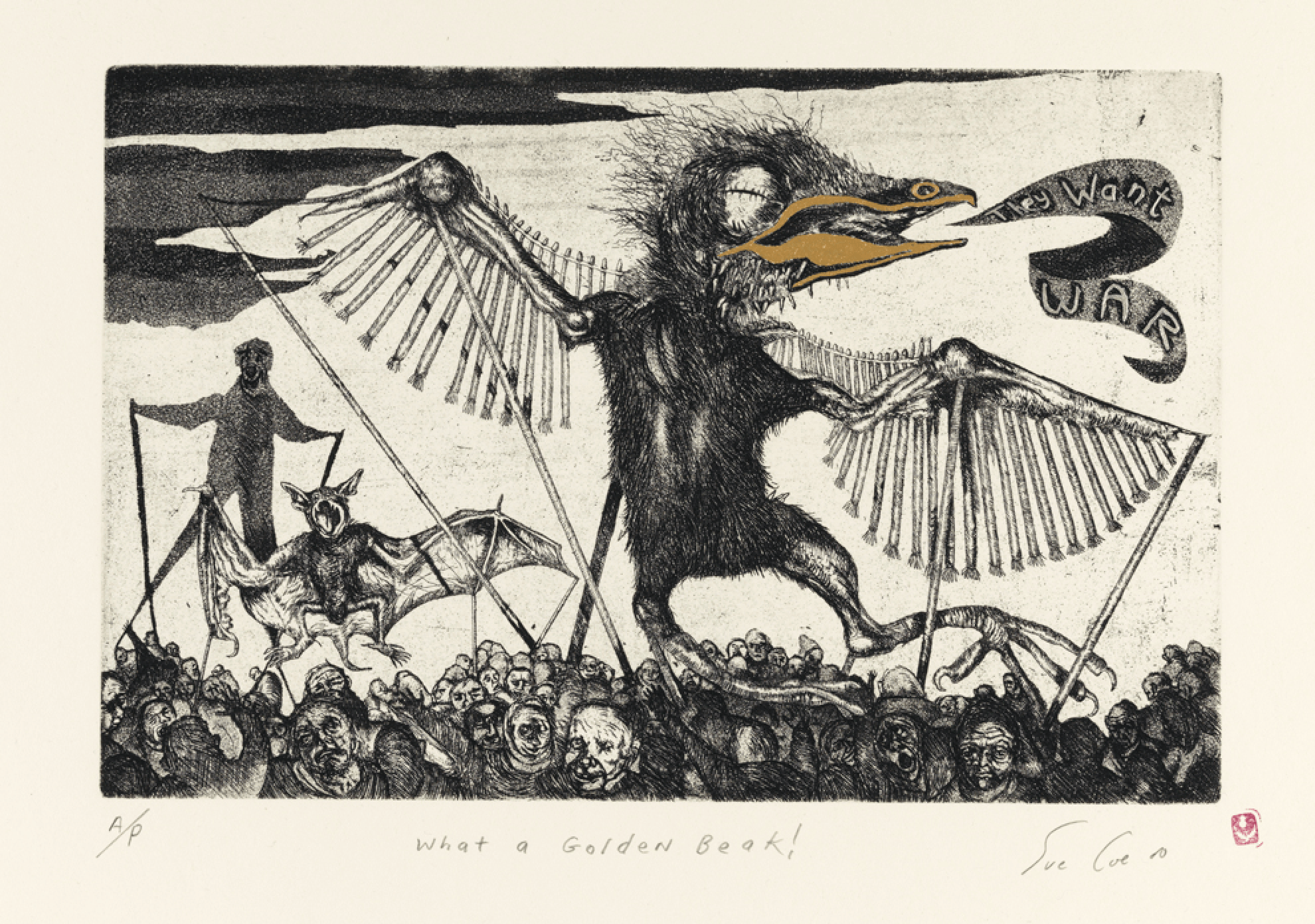

Sue Coe, “What a Golden Beak (They Want War)”, Tragedy of War, 1999-2000. Photo: The artist.

Dear Comrades,

Before I say anything else, let me to extend to Ukrainians my fervent hope for your safety. If you are sheltering with family, friends, or neighbors, please find comfort in companionship, and solace in dreams of better times. If you are a refugee, I hope you have been welcomed with generosity – no one should have to experience what you have. If you are fighting, I wish you success! But please remember that retreat in the face of overwhelming odds is not timidity; it’s tactics.

To Russian artists and writers: I salute your courage in protesting this war. If police repression has made that impossible, please know that others around the world are speaking out on your behalf in opposition to invasion and violence. We understand that many ordinary Russians, perhaps a majority, oppose the war, and want to remove Putin from power. We know just how they feel. How often have we said out loud, under successive U.S. presidents, “Not my war!” or “Not in my name!”

To progressive artists and critics in the U.S., I admire your engagement in issues of war and peace at a time when most creative people and institutions prefer to cultivate their gardens and harvest what rewards they can. I especially applaud you for pondering how best to support Ukraine under siege, while at the same time denying comfort to the cold warriors and arms manufacturers at home that created the conditions for the current conflict and expect to profit from them.

During wartime, aesthetics is often set aside in favor of sheer survival. That’s understandable. But wars are waged with ideas and images almost as much as bombs and bullets, which is why Putin has shut down all independent media, banned public protest, and propagated the naked lie that Russia is not fighting a war at all! And it’s why the Ukrainian president has used every possible image and anecdote – and American public relations firms — to paint a picture of heroic resistance against a much larger and more powerful invading force.

Since the invasion on Feb. 24, many of you – my friends and colleagues in Ukraine, Russia, the U.S. and elsewhere — have been meeting to talk about how to use art to help stop the Russian onslaught and secure peace. Discussions have been spirited. Because I live in rural Florida, safely distant from the combat zone, (not withstanding Governor DeSantis), I have mostly abstained from these conversations. But the truth is, I’m deeply implicated in this war; so is every American. Putin would not have invaded Ukraine but for the specter of U.S. and NATO expansionism. We are the enemy; Ukraine is the proxy. The U.S. is far away and armed to the teeth; Ukraine is close and comparatively weak. That’s why Russia attacked. This fact is obvious but rarely said. We are responsible for Ukraine’s suffering, almost as much as Russia.

So, my friends, here are the two questions I most want us to address in our next meeting:

1) How can we best deploy art to challenge Russian violence and irredentism, while at the same time attacking U.S. and NATO imperialism?

2) How can artists and critics challenge the madness of exterminism: the grotesque illogic of nuclear war and the equally mad rush toward climate catastrophe?

We can begin to consider these questions by examining some specific works of art from the past.

Art Against War

I have long admired the work of the British-born, American artist, Sue Coe, so let’s look at her anti-war etching “What a Golden Beak (They Want War), part of a series of 23 prints titled The Tragedy of War (1999-2000). As you well know, serious artists don’t invent ex-nihlio; they build upon what has come before. Coe fits that model to a t. She is very conversant in the long history of art against war. Her suite recalls Jacques Callot’s similarly titled set of 18 etchings called The Great Miseries of War (1633), and Francisco Goya’s collection of 80 etchings and aquatints titled The Disasters of War (c. 1810-15).

In these prints, Coe represents violence abroad and at home. She alluded in the series to the U.S. and NATO bombing of Yugoslavia in Spring 1999, the scourge of American gun crime, the targeting of innocent children, and many other tragedies of war. She also indicted American and European war mongers in a pair of prints titled “War Street” which shows a Wall Street bear and bull watching Death on a pale, carousel horse; and “What a Golden Beak (They Want War), which depicts a dead bird-fetus hoisted like a puppet above a teeming mass of leering faces. Behind the carcass are two more marionettes: a bat with mouth wide open, and the effigy of a man. The bird’s beak is gilt, as if to suggest that for a war profiteer, death is pure gold.

Coe’s “What a Golden Beak” recalls Callot’s etching from the Miseries titled “L’Estrapade” (“Strappado”), which shows in the middle ground a man hoisted in the air by his wrists, and in the right foreground, another man trussed up, preparing to suffer the same fate. Three centuries later, strappado was deployed by the Nazis for purposes of torture and interrogation, and still later, by the CIA at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. In that instance, the prisoner, Iraqi national Manadel al-Jamadi, was killed.

Jacques Callot, “L’Estrapade,” Les Misères et les Malheurs de la Guerre, 1633. Photo: The author.

A more obvious source for Coe was three prints by Goya: “¡Que pico de oro!” (What a Golden Beak!”) from Los Caprichos (1799), “El sueño de la razón produce monstruos,” (“The sleep of reason produces monsters”) also from Los Caprichos, and “Que se rompe la cuerda!” (“The rope

is breaking”) from The Disasters of War (c. 1810-15). From each print, Sue selected a single motif – a parrot, a bat, and a tightrope walker – to convey a complex, new idea: that a

multitude of war profiteers have constructed a political zombie that can ventriloquize their greed.

Francisco Goya, “Que se rompe la cuerda!” (“The rope is breaking”), The Disasters of War, c. 1810-15. Photo: The author

Of course, the meaning of Coe’s work is not so literal. It’s also about the divide between performance and spectatorship; the relationship between individuals and mobs; and

the conflict of innocence and experience. No artwork of value can be reduced to a single, articulable “message;” if it could, its very existence would be unnecessary. You know this well. But Coe’s print series is concerned to warn us about the risks posed by weapons manufacturers, the aerospace industry, fossil fuel companies, security consultants, investment bankers, pipeline developers and the rest of the vampires who “want war” and live off death. And her cautionary remains salient today. The war in Ukraine is a tragedy for the many, but a bonanza for a few.

War Profiteers

The war against Ukraine and the economic sanctions against Russia have disrupted the global market for oil and natural gas, raising the price for both to record levels. The war has also greatly increased demand for advanced weapons and aircraft. Fossil fuel companies and arms manufacturers are practically chortling. Any losses BP and Shell may incur from their withdrawal of stakes in Russian oil and gas giants Rosneft and Gazprom, will be more than made up for by increased profits from rising fuel and share prices. Even before the war, the oil and gas companies were doing very, very well. Shell earned $6.4 billion in profits in the last quarter of 2021. Shell’s CEO, Ben van Beurden had a total compensation last year of about $10 million. In February 2022, he collected a cool $5 million from the sale of Shell stock. ExxonMobil made almost $9 billion in the fourth quarter, and its CEO, Darren Woods made about $15 million, $8 million or so from stock options.

Not content with record profits and executive profiteering, the oil industry trade group, the American Petroleum Institute, which represents Exxon, Shell and Chevron, wants more. In the wake of the war and possible shortages, they are asking the Biden administration to relax extraction regulations and open up drilling on federal lands and off-shore to “ensure energy security at home and abroad.” They have not proposed rapidly expanding the use of renewable energy, though this would accomplish the same thing cheaper and faster and at much less cost to the environment and climate.

Here’s another example of an energy company profiting from war: Cheniere Energy, the largest U.S. exporter of Liquified Natural Gas, which reported record profits in 2021, saw its share price last week rise almost 8%. Eager to allay any anxiety about gas supplies, Cheniere’s vice president, Anatol Feygin, said his company’s tankers would be “a key part of the solution going forward.” He added: “The human toll and tragedy [of war], obviously has our thoughts and prayers.” Coincidentally, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reported last week that global temperatures are rising faster than expected and that record droughts and rising seas will cause catastrophe – hunger and malnutrition, displacement and early death – for millions in the next few decades unless immediate action is taken to reduce the emission of global greenhouse gasses. Feygin and Cheniere did not publicly address the IPCC report. War, fossil fuels and climate catastrophe are evil triplets.

As the world’s leading producer or fossil fuels, the U.S. is the chief culprit in the climate crisis. It is also the world leading producer (37% share) of armaments, followed by Russia (20%), France (8%), Germany (5%) and China (5%). It’s home to the planet’s five biggest arms manufacturers, led by Lockheed-Martin, which logged $67 billion in sales in 2021. Lockheed makes Stinger and Javelin missiles, currently in great demand by Ukraine and all other nations in the region. The looping trajectory of Javelins allows them to hit tanks from above, making them very effective at penetrating the commander’s hatch and incinerating the crew. U.S. defense contractors donated almost $50 million to both Democratic and Republican campaigns in 2020, led by Lockheed-Martin with about $6 million, followed closely by Raytheon and Northrop Grumman with more than $5 million each.

Coe’s etching, “They Want War,” we have seen, is a highly mediated work of art that is part of a long tradition of anti-war images stretching back at least 400 years. But it effectively evokes the current drive for profit of some of the nation’s largest and most powerful corporations. Radical art today isn’t primarily about reporting the facts – that’s the essential work of journalists. It’s about making militarism and capitalism emotionally and intellectually vivid, the better to be resisted. “The weapon of criticism,” Marx wrote in 1843, “cannot, of course, replace criticism of the weapon; material force must be overthrown by material force; but theory also becomes a material force as soon as it has gripped the masses.” Replace the word “theory” in Marx’s famous quote, with “art” and you have a pretty good idea of the potential power of art in the context of a mass movement against war and empire.

Art of the Meme

By now you are probably asking yourselves who are the Sue Coes (apart from Coe herself) of the current anti-war, anti-imperialist struggle? The answer for the moment is unclear. Serious art takes time, and it is only in the next few weeks and months that we’ll begin to see what the world’s best artists have to say about the current crisis, and how they will forge links with emerging protest movements. So far however, the most arresting art consists of memes supporting Ukraine and condemning Russia. For example, the unsigned, unattributed, widely distributed internet montage of Putin using a dart to burst a Ukraine-flag balloon but exploding himself. The image is a clever inversion of the scene from Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1940) in which Adenoid Hynkel (the Hitler character played by Charlie) toys with a balloon-earth, only to have it blow up in his face.

Charlie Chaplin in The Great Dictator, written, directed, and produced by Charlie Chaplin, 1940.

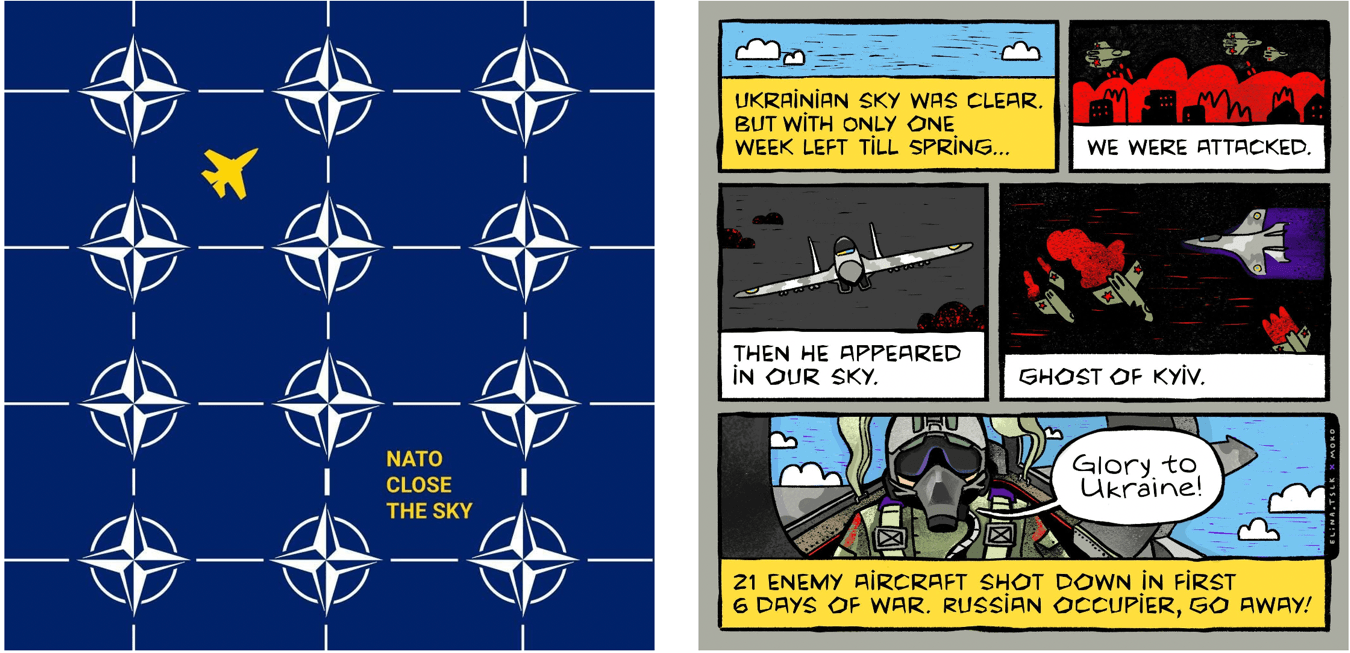

Other memes, especially by Ukrainian artists, are still more tendentious. The ones posted online by Katerina Korolevtseva and the Projector Creative & Tech Online Institute were made to be freely downloaded and distributed. Their most frequent demand is for NATO to

Artem Gusev, Close the Skies, 2022 Elina Tslk, The Ghost of Kyiv, 2022

“close the sky,” meaning establish a no-fly zone over Ukraine. That request was rejected last week by U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken and NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg for the very sensible reason that do so could trigger a U.S. war against Russia and possible nuclear holocaust.

Other designs show Putin as Hitler, Russia as Nazi Germany, and the “Ghost of Kyiv” who single-handedly shot down between six and 21 Russian fighters – the numbers vary according to the teller. Like the widely reported deaths of the 13 border guards on Snake Island who rather than surrender to the Russian navy shouted “Go fuck yourself”, the Ghost figure is fictional. (The guards were not killed; they were captured alive.) Truth, as the expression goes, is the first casualty of war.

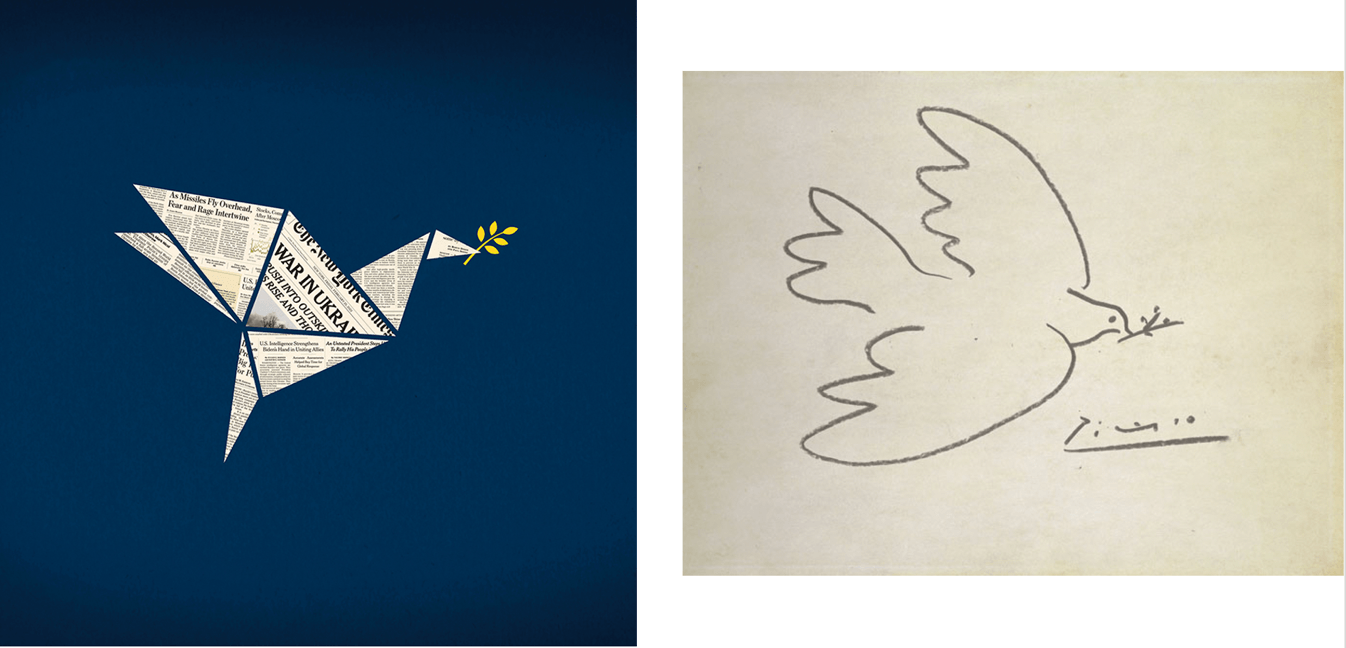

Another effective, but less partisan meme is one by Brett Stiles simply titled Peace, which recalls Picasso’s iconic lithograph from 1949. Stiles updated the image by turning the curves of Picasso’s bird into an angular origami made from a New York Times front page reporting the Russian invasion. Picasso’s bird is notable because it was intended to be an anti-nationalist symbol, condemning all war and violence, but particularly that perpetrated by the U.S.

Bret Stiles, Peace, 2022, courtesy brettstilesdesign.com. Pablo Picasso, Peace, 1949.

Stiles’s meme too rejects nationalism in favor of global peace. (Another dove by Picasso was used on the poster for the second World Congress of Partisans for Peace in Paris in 1949.)

Precisely such images, however, have been criticized by Ukrainian designer Korolevsteva. She writes:

“I think the most useful messages from the international community and from our designers in English are not with doves and calls for peace, but calls to make donations, for example. Or calls to cut Russia off from the international payment network Swift, or to close the sky. When these messages are shared, they lead to action and designers can make a difference in the name of truth and our freedom.”

Whether such memes can in fact “lead to action”, or as Marx wrote, become a “material force,” depends upon conditions of their reception. But the massages of some of them – especially “close the sky” — are historically and politically irresponsible. They invite war between the U.S. and Russia.

The shape of things to come

The memes illustrated here, and many others, fail to effectively characterize the individuals, institutions, and practices responsible for the current conflagration. The fires of war were not lit in a flash by a single, evil genius; they have been long smoldering. NATO expansionism and U.S. impunity infuriated and emboldened Putin and his military. As horrific and inexcusable as is the Russian attack upon Ukraine, the U.S. invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, bombings of Serbia and Libya, and support for the Saudis in their war against the Houthi in Yemen led to vastly more casualties than are likely be suffered in Ukraine. And yet there were no sanctions against the U.S., no war crimes tribunals in The Hague, and no confiscation of the wealth of American oligarchs. To say that is not to excuse Putin’s malignity; only to say that it was a disease that spread from west to east.

What’s needed now, my dear friends, is a global, mass mobilization against this war, U.S. imperialism, NATO expansionism and the fossil fuel and arms industries. Protesters on every continent must condemn the current drive toward self-destruction whether in the form of nuclear war or global warming. Their mantra must be, as it was for the historian E.P. Thompson in 1980, “protest and survive.” A leader of the global Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, Thompson understood the nuclear standoff of his day not simply as the head-to-head battle of a few, international leaders, but as the product, as C. Wright Mills first argued, of the “oligarchic and military ruling classes.” That remains true today, as does the illogic of exterminism:

“Exterminism designates those characteristics of a society — expressed, in differing degrees, within its economy, its polity and its ideology — which thrust it in a direction whose outcome must be the extermination of multitudes. The outcome will be extermination, but this will not happen accidentally (even if the final trigger is “accidental”) but as the direct consequence of prior acts of policy, of the accumulation and perfection of the means of extermination, and of the structuring of whole societies so that these are directed towards that end.”

That “accumulation and perfection of the means of extermination” is the reason why anti-war art that today must be similarly broad, international, and inclusive in its messaging and scope. Patriotic memes simply won’t do, no matter how much they may bolster the morale of heroic partisans in Ukraine. It’s necessary to recall, once again, that the citizens of that country aren’t the prime targets of the current war, even if they are so far, its only victims. The U.S. and NATO are Russia’s main targets, which also makes them – along with Putin and his oligarchs — the war’s instigators.

The new, anti-war art I’m calling for must demand peace negotiations now, based upon concessions from all sides. The terms of a resolution are obvious: a phased Russian withdrawal in exchange for the slow lifting of sanctions; political neutrality for Ukraine, including an agreement not to join NATO for the foreseeable future; a deal between the U.S. and Russia to pull back missiles from each side of the Russia/NATO borderland; nuclear arms reduction talks; and immediate, joint action to reduce the emission of greenhouse gasses. (There is no use stopping one catastrophe while continuing to accelerate another.) Ukrainians may not like some of these terms. But to forestall further suffering and death, a negotiated settlement is required — what Noam Chomsky calls “an escape hatch with a grimace.”

As we begin to come together in protests, we also need to gather our creative energies in support of a few basic ideas that will inform a veritable flood of memes, signs, posters, banners, screen prints, etchings, woodcuts, paintings, sculptures, performances, aesthetic practices, essays and works of criticism.

No to the Russian invasion of Ukraine!

No to Russia’s attack on dissidents!

No to war!

No to U.S. militarism!

No to U.S. imperialism!

No to global fascism!

No to NATO!

No to exterminism!

Yes, to peace, yes to negotiation, yes to compromise!

Protest and survive!

Many great artists have preceded us in protesting war, imperialism and fascism in the 20th Century, including Otto Dix, George Grosz, John Heartfield, Norman Lewis, Leon Golub, Nancy Spero, Martha Rosler, Rudolf Baranik, Pablo Picasso, David Alfaro Siqueros, and Kathe Kollwitz. Now is our time to make art that will help stop the gathering momentum of violence, catastrophic climate change, and exterminism.