LONDON METALS EXCHANGELME rips up its free-market rule-book to tame wild metals

Reuters | March 17, 2022 |

The LME said the committee was likely to include representatives of nine companies.

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

You can tell the London Metal Exchange (LME) is new to price limits.

The venerable 145-year-old institution’s first attempt to restart its broken nickel market was over in chaotic minutes on Wednesday as the price immediately fell to – and briefly through – the lower 5% daily limit at $45,590 per tonne.

Thursday’s restart with a widened 8% price band also misfired.

The LMESelect electronic trading platform evidently hasn’t read the memos and keeps allowing small numbers of trades to be executed outside of the new limits.

These trades have been cancelled as were those booked on the March 8 melt-up prior to the market being suspended.

The system’s inability to react to the new trading reality is symptomatic of the tectonic upheaval playing out in the forum for global metals pricing.

The LME has for years epitomised the United Kingdom’s light-touch regulation of its financial services sector but a history of last-minute intervention in disorderly markets looks to be over. The last few days have brought time-spread caps, daily price limits and cancelled contracts.

This is in part due to the LME’s own dysfunction. The nickel crisis has exposed fundamental flaws in the exchange’s regulatory scope.

But it is also because industrial metal markets have turned ever wilder since the start of 2021. The LME may be a damaged lens right now but it is showing up an equally dysfunctional metals market.

Blind-sided

The nature of the short squeeze in nickel – a margin meltdown as China’s Tsingshan Group tried to collateralise its huge short positions – has exposed two regulatory blind spots.

The LME has come in for understandable criticism that it waited too long to suspend the nickel market. The exchange’s compliance department, which has unique insight into trading flows, should surely have seen that something ugly was brewing.

But the LME can only track what it sees. Exchange flows are but the tip of a much bigger metals pricing pyramid, most of it trading over-the-counter (OTC) between producers, merchants, banks and users.

The price risk embedded in often bespoke contracts is channeled to the LME via banks and brokers, who net off differing positions as much as they can before trading any residual risk in the LME system.

What the LME compliance department gets to see is a risk landscape that has been distilled multiple times. Perfect vision on a very narrow screen.

The LME has pointedly noted that “the widely reported large short positions (originated) primarily from the OTC market”. If Tsingshan was sitting in the OTC shadows, the sheer size of its short position may not have been obvious at all.

Nor would any parallel OTC trading strategy. Lost in the media frenzy around Tsingshan and its ebullient owner Xiang Guangda was a March 7 announcement by Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt, Tsingshan’s industrial partner, that it too is facing losses on its nickel positions.

Short sighted

The LME’s difficulties in discerning the true state of positional play have been confounded by a rule-book that interprets market abuse exclusively through the prism of dominant long positions and their ability to squeeze cash metal availability.

Alan Whiting, the executive director of the UK Treasury’s regulation and compliance department, wrote the LME rule-book and even he conceded in 1998 that “while the exchange does not seek to favour shorts, backwardation limits do penalise longs, whereas there is currently no equivalent financial penalty on the misuse of dominant short positions.” (“Market Aberrations: The Way Forward”, October 1998)

The LME explored the possibility of imposing penal margins on dominant shorts but that would require a determination of when a short position is “abusive”, a semantic and regulatory dead-end.

The nickel market’s independent decision to impose its own penal margins on Tsingshan, the trigger for this whole sorry saga, underlines the regulatory dilemma of how to handle a big commodity short position held by a big industry player.

Wild metals

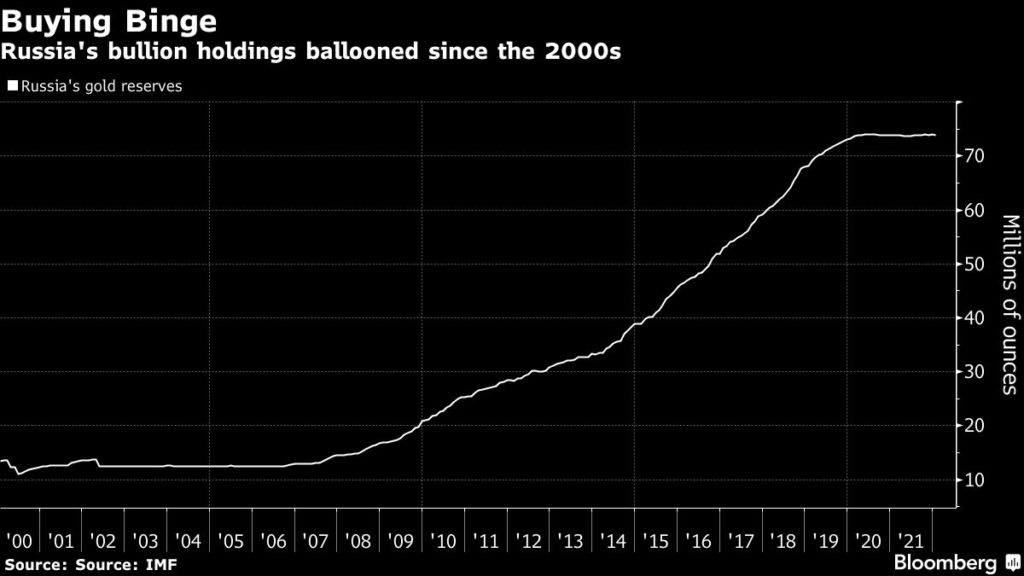

Nickel’s breakdown is intricately tied up with the current crisis in Ukraine, specifically concern around the continued supply of Russian metal to the European physical and LME storage markets.

The exchange cited “geo-political news flow” as one reason for its decision to suspend the contract and what Russia calls its “special operation” in Ukraine is undoubtedly one reason all six core LME contracts are now in special measures.

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/7AY3QI3RKVPZ7BNC5IOEMIXW4U.png)

But Doctor Copper turned wild in October last year, forcing the LME to intervene in its flagship metals contract as available stocks fell to just 14,150 tonnes.

Tin spreads had already gone stratospheric at the start of 2021, the cash premium flexing out to an extraordinary $6,500 per tonne.

Indeed, measured by time-spread turbulence, every LME metal has become much more unstable since the pandemic as global supply-chains have buckled.

Metals such as tin are now pricing in genuine supply scarcity. LME tin took some collateral damage from the nickel suspension, tumbling 21% on March 9. But at a current $41,680 it would still be off any historical chart.

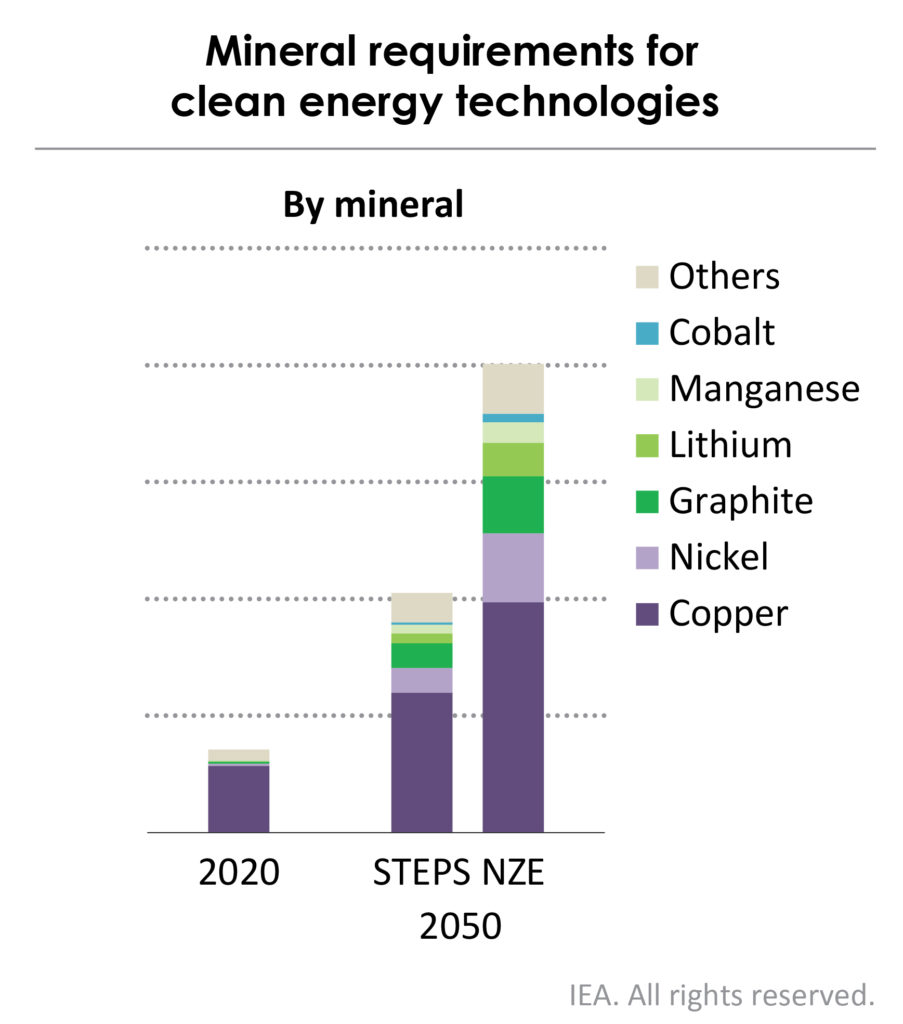

If you believe Goldman Sachs, copper is also heading for scarcity as government spending on green infrastructure accelerates pandemic recovery.

Look beyond the LME and both lithium and cobalt prices have also been on a tear as a rapidly expanding battery supply chain stocks up. Indeed, it was the battery pull on LME nickel stocks that laid the foundations for the short squeeze.

There has been a lot of talk about a metals supercycle and it was starting to take tangible form even before markets had to factor in the possible loss, or at least diversion, of Russian supply.

Higher demand means higher prices and they come with higher volatility.

The LME’s history of laissez-faire regulation rested on an assumption that markets could efficiently be left to price themselves barring the occasional “aberration” requiring intervention.

The synchronised price turbulence across all six base metal contracts challenges that assumption to the core.

That’s why the LME has ripped up the old rule-book. Changed metal markets need a change in rules.

There are some who think it might be time to rip up the LME after last week’s rolling fiasco but the underlying pricing risk won’t go away. Indeed, if the last year is a taster of the metals cycle to come, it’s only going to increase.

(Editing by Kirsten Donovan)

Nickel, the devil’s metal with a history of bad behaviour

Reuters | March 10, 2022 |

The sky in the smoke from the chimneys of Norilsk Nickel plant. (Stock Image)

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

The global nickel market is in a pricing black-out.

The London Metal Exchange (LME) three-month nickel price sits in suspended animation at $48,048 per tonne, Monday’s closing price and the last trade with even a semblance of legitimacy.

Tuesday’s mayhem and the resulting decision by the LME to suspend all trading has frozen what is the core reference price for the global supply chain stretching from miners to stainless steel mills and electric vehicle battery makers.

China is also in black-out. The Shanghai Futures Exchange has suspended trading until Friday.

Today there is no global nickel trading and no price formation.

Related Article: Nickel price spike “purely financial” but Tsingshan effect could linger

It’s a truly shocking outcome but not without precedent.

When German miners first discovered nickel in the fifteenth century, they called it Kupfernickel, or “Old Nick’s Copper”, and it has had a history of devilish behaviour ever since the LME launched the contract in 1979.

The underlying cause of the repeated market disorder has never changed.

Ghosts of crisis past

“The LME contract has been criticised as illiquid, unrepresentative, open to manipulation and volatile”.

Hard to disagree given this week’s extraordinary events but those words were written in 1992 by a former colleague, Simon Clow.

The criticism came hot on the heels of what at the time was known as the nickel crisis of 1988.

On Friday Feb. 25 of that year the LME official ring descended into chaos as one house bid up the cash price from $10,000 per tonne to $15,000 per tonne with not a single offer. The cut and thrust of open outcry came perilously close to physical fisticuffs.

By the standards of the time, the liquidity vacuum and price acceleration were just as shocking as Tuesday’s explosion to $101,365 per tonne.

Ring-trading was suspended for the first afternoon session, which at the time amounted to halting the market, while the LME board held an emergency meeting.

A daily backwardation limit of $150 per tonne was imposed as a condition for trading resuming on the second afternoon ring session. The official ring price was scrubbed on the convenient basis that it had not actually traded.

Fast forward to 2007 and the LME had another nickel crisis on its hands. The year stands out as the previous all-time nickel price high – $51,800 per tonne – but that peak coincided with a ferocious squeeze on cash positions.

The pain for short position-holders became so acute the LME had to change its lending rules, categorising several small dominant long positions as a single entity.

A generous view was that the exchange was forcing affordable liquidity across its raging time-spreads. A less generous interpretation was that it had detected collusion among key players.

Here we are again. Time-spread pain. Extreme volatility. Shorts who can’t cover. And another broken nickel market.

Stand and deliver?

The common theme running through all three crises is one of low exchange stocks and the difficulties facing even some of the largest nickel players in delivering physical metal against LME short positions.

Physically-deliverable contracts such as the LME’s are where paper price meets real-world price and wild outcomes around settlement dates are far from rare – think back to April 2020 when front-month WTI oil settled at a negative $37.63 per barrel.

Settlement stress, however, is compounded on the LME by a rolling daily prompt date structure, which can translate into daily premium pain for a short unable to deliver physical metal as an exit route.

And nickel has delivery issues which are all its own.

“Part of the problem, critics say, is linked to the structure of the contract,” Clow wrote in 1992, explaining, “only a minority of the nickel produced every year is deliverable against the LME contract (…) LME stocks represent only a small percentage of worldwide production.”

That is as true today as it was back then.

Only Class I nickel, defined as nickel with greater than 99.8% purity, is deliverable against the LME contract.

Nickel comes in multiple forms and guises – nickel pig iron, nickel matte, ferronickel, nickel sulphate – all of which need to be price-hedged on the LME but none of which can be delivered.

The Shanghai market is no different. If anything it’s more restrictive due to the limited number of registered non-Chinese brands.

Nickel is a small market by comparison with other base metals with global consumption of around 2.77 million tonnes last year, according to the International Nickel Study Group.

Less than half of that is exchange-deliverable and the ratio is shrinking all the time.

Broken pricing

Indonesia, the world’s driver of primary production growth, doesn’t produce nickel in Class I form.

Tsingshan, the Chinese company at the epicentre of the current storm, has massive nickel capacity in Indonesia but its metal is either flowing directly into its stainless steel meltshops or being converted into intermediate products for shipment to Chinese battery makers. None of it is Class 1.

Whatever the mix of price hedging and speculative overlay in the company’s positioning, the short play ultimately had no physical delivery escape path.

Others may have fallen through the same price-delivery gap. The LME’s latest positioning report shows four significant short-position holders on the main March prompt date. If those are hedges against anything other than Class I, the owners are in the same pickle.

Nickel’s deliverability issue has dogged the LME contract since launch. There was intense industry discussion in the 1990s about the disconnect between exchange and supply-chain pricing.

But finding good-delivery criteria for a highly variable product such as ferronickel, which can grade between 20% and 40% with a wide spectrum of iron content, proved impossible.

The stainless steel sector, historically the largest user of nickel, evolved a surcharge system to try and mitigate and pass through nickel’s price volatility, but at the occasional cost of generating an echo-effect in the stainless stocking cycle.

Nickel sulphate, a fast-growing process stream which is destined for battery makers but is also not exchange deliverable, opens up another potential rift in the pricing landscape.

The London Metal Exchange is facing a lot of pressure to think harder about how it manages markets such as nickel after this week’s chaos.

But the nickel market also needs to think a lot harder about how it wants to handle its pricing risk.

(Editing by Elaine Hardcastle)

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/7AY3QI3RKVPZ7BNC5IOEMIXW4U.png)