LONG READ

Recent discoveries of gas fields under the sea in the Eastern Mediterranean fuelled the long existing troubles between Turkey and its neighbours, especially Greece and the Republic of Cyprus. Turkey’s assertive policy on this issue prompted Greece, Cyprus, Egypt, and Israel to intensify their mutual cooperation on exploitation and commercialization of natural gas, thus intensifying Ankara’s concerns over being denied its share of energy resources (Merz, 2020, p. 1). The background of relations between the regional actors warns that the dispute goes beyond “mere” exploitation of natural gas and warns that the energy problem could be just the beginning of a more serious crisis. The main question thus is whether the dispute can be solved through cooperation and interdependence, or whether it will develop into a more serious conflict. The solution to this question largely depends on the stance of the European Union, which has the responsibility to broker a peaceful end of the crisis involving two of its members and one accession country.

As mentioned, gas exploitation is a reason, not the cause, of the crisis, and, as summarized by G. Dalay, the maritime dispute between Greece and Turkey, as the core of the current situation, centred over three main issues: 1) disagreement over Greece’s sea borders and ownership of some Aegean islands; 2) exclusive economic zones in the Eastern Mediterranean, and 3) the long-lasting dispute over the Cyprus issue (Dalay, 2021, p. 1).

Current energy concern, thus, adds to the already existing tensions in the region, especially between Turkey on one side and Greece and Cyprus, on the other. Since the latter two are also member states of the EU, the problem is not just regional, but involves the whole Europe, questioning Turkey’s aspirations to EU membership and estranging it from its NATO allies.

Concrete Turkish actions, which include deploying expeditions into Greece’s and Cyprus’ waters, blocking Cyprus’ vessels, and signing a treaty with the Government of National Accord in Libya (Merz, 2020, pp. 1-2), provoked EU to back Greece and Cyprus against Turkey, with some states, like France, demanding more comprehensive sanctions against Turkey. France has also sent navy and participated in military exercises in the region together with Greece and Cyprus, thus warning Turkey (Ibid.).

On the other hand, Turkey clearly sees itself as a major player in the region, and its activities go beyond gas exploration and exploitation. In 2019 Kudret Ozersay, foreign minister of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, confirmed as much by saying that ‘the Eastern Mediterranean region has vital importance for Turkey geopolitically, geostrategically, and in other aspects’. In a way that resounds with strong sympathies for Turkish regional politics, Ismail Telci summarized this vital importance in a piece written for Politics Today by expounding four main reasons for Turkey’s strong interest in the Eastern Mediterranean.

First, Turkey is a large energy importer, dependent on countries like Russia and Iran for fulfilling its energy needs, and thus finding its own energy resources is crucial for Turkey. Second, Turkey aspires to become a major energy transfer hub, connecting Europe with Middle Eastern and Asian markets, which contributes to Turkey’s geostrategic and economic standing. Third, Turkey’s policies in the Middle East are facing confrontation from Egypt and Israel, which, together with Greece and Cyprus, are attempting to isolate Turkey from regional politics by forming alliances, and so Turkey must respond by taking a more active role for this power struggle. Finally, Turkey sees the Eastern Mediterranean region as a question of national security, and thus its actions should be seen as a line of defense against other actors’ possible threats.

Telci concludes his opinion by stating that ‘regional and international actors must remember the fact that the Eastern Mediterranean has been a Turkish inland sea for centuries and historical fact will be the center of Ankara’s future strategies towards the region’. Such direct statements clearly show that Turkey’s behavior in the region is only partly motivated by questions of energy and/or economy, but actually have a more profound geostrategic significance, which has obviously come to dominate Turkish policy towards the Eastern Mediterranean.

These most recent assessments of Turkey’s actions and the ever-growing feeling of an imminent conflict seem to contradict the more optimistic opinions voiced over the years, such as the one expressed by Ross Wilson, former US ambassador to Turkey, who wrote in 2014 that the ‘discovery of offshore natural gas in the eastern Mediterranean gives the decades-old stalemate between Turkey and Cyprus an opportunity cost price tag – it provides dollars-and-cents reasons for easing the estrangement or bringing it to an end’. (Wilson, 2014, p. 105) Similar views were expressed by the then US Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs, Victoria Nuland, who hoped that gas resources would bring to the settlement of Cypriot issue and would have positive consequences across the Eastern Mediterranean and for the NATO-EU relations.

These unfulfilled prophecies clearly show it is not energy that is at stake in the region, and that no “dollars-and-cents” reasons can play decisive role in the solution of the issue. Already in 2012 scholars have identified the complementarity of Turkey’s assertive rhetoric in the Eastern Mediterranean with the majority of domestic population, which wants to see the country as powerful and determined, but also warned about the need to determine the possible directions in which Turkey wishes to go:

One question that arises is what sort of regional power Turkey wants to become. At this stage, there are a number of options for Turkey. It might emerge as an over-assertive power aiming to become the region’s hegemon, defending what it perceives as its national interests while tightening ties with all regional actors. It might side with the West, thus selecting regional actors to partner with and others to keep at arms’ length. Or, finally, it might try to strike a balance between these two options, cultivating relations with a vast array of states and non-state actors in the region, while remaining anchored to the Euro-Atlantic alliance. In this context, what Turkey needs to avoid is taking steps that might have unexpected consequences eventually resulting in greater regional instability (Ogurlu, 2012, p. 13).

In understanding the way in which Turkey has decided to behave in the end, one needs to go back to the beginning and take into account the issues that go beyond gas exploitation. I posit that there are three main reasons for Turkey’s behaviour. The first is the understanding, going in line with a realist prospective, that states value security more than prosperity, and that economic incentives are insufficient reason for cooperation. Second, Turkey has undergone a shift in its foreign policy, which moved from “zero problems with neighbors” in the first years of Erdogan party’s (AKP) rule to a desire to revive or emulate the Ottoman Empire’s power (Merz, 2020, p. 3). Third, a rather ambivalent European stance towards Turkey and EU’s apparent inactivity in the crisis contribute to intensifying the negative aspects of the first two points.

Over the past two decades, countries of the Eastern Mediterranean signed several agreements on exclusive economic zones (EEZs) – in 2003 Cyprus signed an EEZ agreement with Egypt, and four years later with Lebanon, while in 2010 Cyprus and Israel sign a deal to define their respective EEZs. All of these deals were fiercely protested by Turkey, which, on its part, signed a continental shelf delimitation agreement with the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus in 2011 (Demiryol, 2019, p. 453).

As already stated, gas exploitation per se is not the main issue for Turkey, but it is part of a complex problem, which includes Turkish-Greek dispute over areas in the Aegean, and more importantly the dispute over Cyprus. The reasoning behind Turkish actions seems to indicate that if Turkey accepted the already signed EEZs or even attempted to build its relationship with other regional actors on principles of cooperation instead of confrontation, it would implicitly recognize Greek claims in the Aegean and accept the status of Cyprus, which would in turn compromise its national security and its desire to win the regional power struggle.

The dispute over EEZs ensued a series of confrontations, and also undermined the peace process in Cyprus, with unification talks in 2014, 2015, and 2017 ending without any positive outcome. In addition, in 2019 Turkey singed two agreements with the Government of National Accord of Libya, namely the Delimitation of Maritime Jurisdiction Areas in the Mediterranean Sea and the Security and Military Cooperation Agreement – the former stated bilaterally the EEZs of Libya and Turkey, completely disregarding Greek major islands. Having this in mind, it is clear that ‘the interlocking set of maritime disputes between Turkey and Greece is strongly tied to their conflicting projections of national sovereignty’ (Dalay, 2021, pp. 2-3) and security. These considerations and Turkey’s behavior would seem to corroborate the realist stance that, at least in the East Mediterranean case, states are prone to value more security and accumulation of power over economic gains achieved by cooperation (Demiryol, 2019, p. 437).

This brings to the second point – the Turkish foreign policy, which, in the region of the Eastern Mediterranean, has been divided into two strands in the past four decades. For the first twenty years, since the 1980s, Turkey’s policy in the region was trade- and diplomacy-driven, while it received a new “face” in the 2000s with the rise of AKP.

The AKP governments were rather oriented towards making Turkey an important factor in the region, and the moves in that direction ‘gradually redefined the country’s regional interests, policies, and alliances’ (Ogurlu, 2012, p. 8). In shifting its foreign policy, Turkey used its Western alliances, mainly NATO of which it is a member, and by acting as a bridge between Asia and Middle East it attempted to increase its regional role. Ogurlu describes this shift as follows:

Turkey has created the conditions to achieve its ultimate goal in the Eastern Mediterranean region: become not only a key player, but also a leading – if not the leading – actor in the Eastern Mediterranean. In other words, Turkey has moved from being a compliant member of the Western community to being an assertive power with the potential of shifting the strategic balance of the whole region. Against this backdrop, Turkey is extremely sensitive to developments that can undermine its current status in the Eastern Mediterranean. Ideally, Ankara would want to consolidate its position by way of increasing its soft power, most notably its ever more important role as an Eastern Mediterranean economic hub. Where this turns out not to be possible, Ankara is willing to confront those regional actors that, deliberately or not, curb its regional ambitions. In this extreme derogation from, if not outright reversal of, its “zero problems with the neighbours” policy, Turkey has started to formulate its strategies and policy in competition with other regional actors that have apparently been shaping their regional approach according to an “enemy of my enemy is my friend” mentality – e.g. Israel and Cyprus (Ogurlu, 2012, p. 9).

This shift into policy towards a “neo-ottoman” kind has seen Turkey confronting its Western allies as well as regional actors. By doing so, Turkey inevitable decreased the quality of its relations with NATO and the EU, but it also provoked complications with Egypt and Israel. Beyond the issues of gas exploration, Egypt has not appreciated Turkey’s constant support for Muslim brotherhood, while Israel does not welcome Turkey’s new support for the Palestinian cause (Merz, 2020, p. 3).

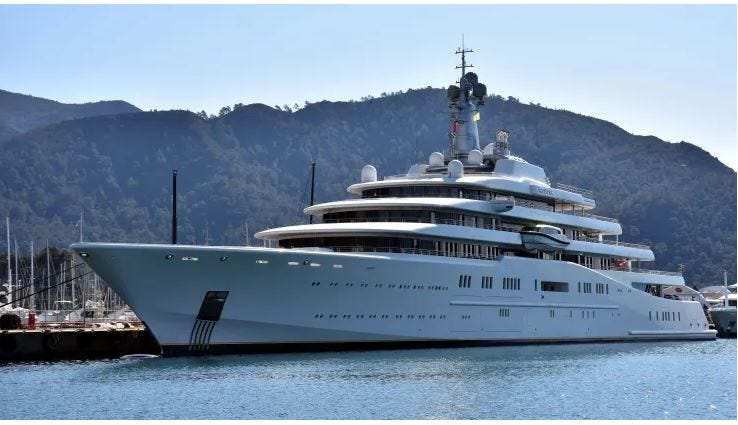

An additional dimension of Turkish foreign policy is represented by the so-called “Blue Homeland” doctrine, which never gained official recognition, but serves well to address certain aspects of Ankara’s behavior. The doctrine basically expounds the fear that Turkey might be ‘caged to Anadolia’ and thus needs to expand its influence over Black Sea, Aegean, and the Mediterranean. The doctrine clearly advocates for an expansion of Turkey’s maritime boundaries and repositions it as a serious maritime power. (Dalay, 2021, p. 6) Interestingly enough, the drilling and seismic research vessels deployed by Turkey in the Eastern Mediterranean gas exploitation are named after Ottoman rulers, such as Fatih and Yavuz, or Ottoman admirals, such as Barbaros, Kemal Reis, and others (Tas, 2020, p. 17).

The change in Turkish foreign policy together with its complicated relations with regional powers, NATO, and the EU, bring the latter into the picture. Turkey applied to become member of the EEC in 1987, while it was granted candidate status in 1999, with accession negotiations starting in 2005. The attitude of the EU towards Turkey has been marked by significant ambivalence. Turkey was often perceived as a buffer zone, or an insulator, which would protect the European security complex from various conflicts in the Middle East, and many in Europe wanted Turkey to remain as such, in order not to bring external EU borders too close the conflicting zones, and proposals were made that EU and Turkey should find alternatives to Ankara’s full membership (Buzan & Diez, 1999).

Some have also wondered ‘whether a semi-developed Islamic country could in fact be regarded as European – the boundaries to the New Europe had to be set somewhere, after all – and also whether post-Cold War Turkey’s strategic significance was now so compelling’ (Park, 2000, p. 34). Such views clearly reflected the European attitude that there was no rush in accepting an Islamic country, which served well the Western interests during the Cold War and could still serve as an insulator towards the Middle East, into the company of other European Union member states.

However, with the official candidacy granted to Turkey some have changed their views. An interesting example is T. Diez, one of the authors of the “alternatives to membership” proposal mentioned earlier, who in 2005 changed his opinion and argued for the Turkey’s faster integration into the EU. The reasons for this change of view are now, fifteen years later and in the middle of Turkish confrontation with its neighbours, especially amusing:

Turkish domestic and foreign politics has undergone what can only be called a revolution: sweeping constitutional and legal changes have been approved by Parliament, a party with religious roots has been elected to form a single-party government, relationships with Greece have become as between friendly neighbours (although not free from conflicts), and the Turkish government has pressed for a solution in Cyprus and has openly backed the United Nations (UN) Secretary-General’s plan for the new constitution of a federal Cyprus Republic, which was eventually rejected not by the Turkish but by the Greek Cypriots (Diez, 2005, p. 168).

These positive “revolutionary” moves were, in fact, in Diez’s view, due to the rise of AKP, Erdogan’s party, still in power sixteen years later:

In Turkey, at least three interconnected developments have had a profound impact on Turkey-EU relations: the improved relationship between Turkey and Greece; the series of reform packages approved by the National Assembly to bring Turkey’s constitutional and legal system in line with EU requirements; and the rise of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) as a secular party with religious roots (Diez, 2005, p. 170).

Now, having in mind that it is the same party (AKP) that seemed to be a factor of stability, modernity and good neighbourly relations in 2005, and that five years later turned Turkish policy in an expansionist and aggressive direction, which continues to this day, one might wonder whether this shift was inherent in the AKP, or was in a sense triggered by EU enlargement fatigue after 2004? In other words, did the AKP, at the beginning of its rise, just to pretend to be a European-oriented, secularist and pacifist party, and then showed its real face after accumulating more power, or was this change caused also by EU’s inactive role in the region and its perhaps pejorative view of Turkey?

This question will most probably remain without a definitive answer, but it seems quite plausible that decades of EU’s ambivalent attitude towards Turkey and the exhaustively prolonged accession negotiations, which now repeats itself in the Western Balkans, might have contributed to radical changes in Turkey – both in its populations, and in the AKP which has often been called populist in formulation of Ankara’s domestic as well as foreign policy, including the one in the Eastern Mediterranean (Tas, 2020, pp. 14ff).

While the EU has been busy with the painful Brexit issue and self-reflection on the future structure of the Union, Turkey might have responded to Brussels’ enlargement fatigue with its own “waiting room fatigue” and decided to reshape its foreign policy in a more assertive and aggressive way, which can now be seen also in the Eastern Mediterranean. Thus, a more active role of the EU in the region, especially since the involved parties are two EU member states and one candidate state, is necessary in order to reach a peaceful solution of the crisis. This can hardly be achieved by threats and sanctions or heavier military presence in the region, which could enrage Ankara even more. Apart from negotiations with the aim of de-escalating the situation, one of the possible options is a more cooperation-prone stance of the EU, especially since the formation of the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum in January 2020, comprising Cyprus, Egypt, France, Greece, Israel, Italy, Jordan, and Palestine.

It is still not too late to facilitate Turkey’s joining the Forum, thus bringing it at the table and trying to prevent a larger-scale conflict. Peaceful cooperation, envisioned in Schuman’s plan for France and West Germany that originated the idea of EU, can be achieved only by genuine cooperation based on mutual respect, not by decades-long and ever-prolonged promises. Thus, the Eastern Mediterranean situation represents an opportunity also for the EU to rethink its enlargement and cooperation policies. However, with the Ukraine crisis and yet another shift of EU foreign policy’s attention, it is still to be seen whether this opportunity will be seized.

References

Buzan B. & Diez, T. (1999), “The European Union and Turkey”, Survival, 41:1, pp. 41-57.

Dalay, G. (2021), “Turkey, Europe, and the Eastern Mediterranean: Charting a Way out of Current Deadlock”, Brookings Doha Center Policy Briefing, pp. 1-15.

Demiryol, T. (2019), “Between Security and Prosperity: Turkey and the Prospect of Energy Cooperation in the Eastern Mediterranean”, Turkish Studies, 20:3, pp. 442-464.

Diez, T. (2005), “Turkey, the European Union and Security Complexes Revisited”, Mediterranean Politics, 10:2, pp. 167-180.

Merz, F. (2020), “Trouble with Turkey in the Eastern Mediterranean”, CSS Analysis in Security Policy, 275, pp. 1-4.

Ogurlu, E. (2012), “Rising Tensions in the Eastern Mediterranean: Implications for Turkish Foreign Policy”, Istituto Affari Internazionali Working Papers, 12:4, pp. 1-14.

Park, W. (2000), “Turkey’s European Union Candidacy: From Luxembourg to Helsinki – to Ankara?”, Mediterranean Politic, 5:3, pp. 31-53.

Tas, H. (2020), “The Formulation and Implementation of Populist Foreign Policy: Turkey in the Eastern Mediterranean”, Mediterranean Politics, latest articles (online), pp. 1-25.

Wilson, R. (2014), “Turks, Cypriots, and the Cyprus Problem: Hopes and Complications”, Mediterranean Quarterly, 25:1, pp. 105-110.

Further Reading on E-International Relations