The Middle East's situation might be slowly improving, but old certainties are being shattered in the ongoing fight to preserve the world's most precious sites

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/NLAHU6GGOYWPOKL2TMOIJ6JHUU.jpg)

A statue wrapped up for protection in the Ukrainian city of Lviv. AFP

The end of the Second World War was perhaps the strangest, most tragic phase of the conflict, as jubilation mixed with understanding of the true extent of the epoch-defining horror that had taken place during just six years.

It was also very complicated, involving many agonised decisions. After a conflict that broke so many norms, Allied powers had the difficult task of striking a balance between mercy and force to make clear that the Axis had well and truly lost. For the US, dropping nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan was the answer. In Europe, Britain led campaigns to firebomb the German city of Dresden, sometimes known as the “terror bombing”, which almost totally destroyed the city in just three days.

Both strategies remain controversial to this day, largely because of the number of civilians killed and injured. More than 100,000 people are thought to have died in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Upper estimates put the total number of dead in Dresden at 250,000.

As well as the human cost, the campaigns are also controversial for what they did to world heritage. Dresden was a medieval-era city of significant architectural and cultural importance. Constructed largely from wood, almost none of it survived. Hiroshima and Nagasaki were similar. Former US secretary of war Henry Stimson is credited with stopping the same happening to Kyoto, a city that today has 17 World Heritage Sites. He cited its cultural significance as a key reason for sparing it.

These individuals and organisations deserve this recognition. They protect not just buildings, but the memories associated with them and the identities they underpin.

In recent years, their work has been desperately needed in the Middle East. Conflict, particularly in Iraq and Syria, has destroyed many of the remnants of some of the world’s most ancient societies. Examples include the Temple of Bel at Palymra in Syria, which was blown up by ISIS in 2016, and, in Iraq, the 12th-century Al Nouri Mosque in Mosul. On a more mundane level, lax legal protection, air pollution, poor urban planning and theft affect them even more.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/EVLNXDGCDXLZMG52OS5PGZPUQY.jpg)

But progress is being made, and the outlook in 2022, while not perfect, is certainly better than it has been in recent years. Reconstruction is well under way in Al Nouri Mosque, and the destruction of the Temple of Bel has led to innovative projects to reconstitute and preserve the building and its artefacts digitally, techniques that can now be used around the globe.

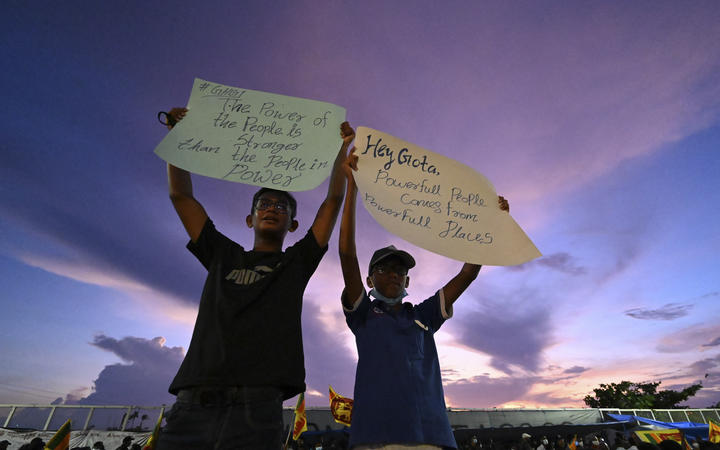

That is not true for other regions, including ones whose worst days of destruction were thought to be behind them. Ukraine, the site of the biggest European conflict since the Second World War, has seven World Heritage Sites, and fighting is taking place in many of its historic cities, including Kyiv, Kharkiv and Chernihiv. Russia, a signatory of the Unesco 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict and which experienced its own devastating destruction during the Second World War, has a legal and moral duty to protect it.

As conflicts rage, instability spreads and environmental crises intensify across the globe, it is important as ever to protect the many millions, if not billions of people who live under increasing threat. Today, it is also important to remember the preciousness of sites that have been comforting and inspiring the world both in war and peace, sometimes for thousands of years, and which today are equally threatened by the same dangers.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/PSHR7PGH256KRQ7GTS74JSV2M4.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/GRADT3DD7BWQ3GI7WGMSGIQQIY.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/TUN3KPS4YSYVZ25VBLZ2QTKEKE.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/JR6XDS6EKJD7JWOSS7OD25NHWE.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/4V7ZZ44NFL3WM647TILAQAL7VI.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/3MUUC3KX77NYNUZDU4HR6W5LWE.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/R7P37HMPQGYI4UV3QJD5FDSGJU.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/4P6XVM75K37LCPPUDSEQB2V5EU.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/LF2D6ECQ4LOTDJL7PU7XW7KBQI.jpg)

:quality(70):focal(-5x-5:5x5)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/ODOT4CDS23OPJ4Y53LDCVJQJ74.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/GMD6DAMOBBDRXBEMH3JOVVH5HE.jpg)