Peter Kalmus: ‘As a species, we’re on autopilot, not making the right decisions’

The Nasa data scientist explains why inaction on the climate crisis pushed him to chain himself to an LA bank – and why trusting in the ‘people in charge’ is so dangerous

Peter Kalmus: ‘I desperately want to feel before I die that

the future is going to be better.

Last month a Nasa data scientist, Peter Kalmus, chained himself to the entrance doors of the JP Morgan Chase building in Los Angeles. A video of a short speech he gave about global heating before he was arrested was shared multiple times on social media. In the clip, voice faltering, he told the public: “I’m here because scientists are not being listened to … we are going to lose everything and we are not joking.” He spoke to the Observer in a personal capacity.

What drove you to nonviolent protest?

It’s this mounting feeling that I need to do more. I have a sense of desperation, because of the wide gulf between what the science says society needs to do and how it feels like everything is heading in the opposite direction. World leaders and people not understanding that we’re in an emergency.

Then the question comes to me, if I’m sitting with the science every day, and I want to protect my kids and young people and non-humans, what do I do? I’ve been on this 16-year journey trying to answer that question, and civil disobedience seemed like something good to try. I’m ashamed to say that it took me this long.

Do you think more scientists should be talking directly to the public about how they feel?

Oh, absolutely. Because we’re not just brains in a vat, we’re humans. The reason oceanologists, ecologists and climate scientists are studying these living systems is because they deeply love them and care about them. Uniformly, across the board, they’re all seeing these massive declines and they’re seeing these systems dying in front of their eyes. I know they’re feeling strong emotions.

Civil disobedience has been far more effective at communicating urgency than anything else I’ve tried.

Last week the UK Met Office said there was a 50% chance that in one of the next five years, 1.5C of warming will be breached. The aviation industry was found to have met only one of 50 climate targets. And a Guardian investigative report revealed that fossil fuel companies are planning huge “carbon bomb” projects that will drive climate catastrophe. That’s a pretty standard week in the global heating news cycle…

This has been just ramping up and ramping up over the years. It’s only going to get more intense as we go forward. That’s why I feel this desperation to end the fossil fuel industry as quickly as possible. Ending the fossil fuel industry is the main thing we need to do to take the pressure off the Earth system and to at least start to stabilise at where we’re at. Then, these news stories will likely start to stabilise as well. But yeah, it’s getting more intense, isn’t it? That’s where we’re at now. That’s a normal week for 2022. What is 2024 going to be like? What’s 2025 going to be like?

The fossil fuel CEOs are rubbing their hands in glee. They can’t believe their good fortune that Putin invaded Ukraine

The mean temperature on the planet keeps going up with every tonne of fossil fuel we burn. At some point you’re going to surpass all of these different milestones. It’s no secret that the fossil fuel industry has been planning to make as much profit as they can from extracting and selling fossil fuel, no matter what happens to the planet, to us, and to future generations. I don’t think we should just talk about future generations any more, because people are dying right now, all around the world. That’s going to happen more as we approach deadly human heat thresholds in certain regions that the human body can’t actually live through. It’s diabolical that these industrialists wish to take short-term profits at the expense of literally everything.

Are the agreements and pledges made at Cop meetings sufficient or effective? Last week the Guardian ran a story revealing how few of the pledges have been acted on…

The esteemed climate scientist Michael Mann, right after Cop26, wrote an op-ed where he proclaimed victory. He said Cop26 was not a failure. I wrote an op-ed the next day saying that it was absolutely a failure, and that it’s very dangerous not to recognise it as a failure, because that, again, decreases the urgency of dealing with the problem. If we consider that as not a failure, what happened at Cop26, then the public can sort of have this feeling that the “people in charge” are doing what they need to do, which is absolutely not the case. They’re not doing what they need to do.

The fossil fuel industry has deeply penetrated politics and even the Cop process itself. It will do everything it can to throw a monkey wrench in the works and to delay action. It’s up to the leaders of the world to stand up to that and to say: “A livable planet is more important than your profits. We are not going to allow this process of delay to continue.” What worries me is that, in this critical year between Cop26 and Cop27, every signal that we’re getting from world leaders is that fossil fuels will continue to expand.

President Biden is begging Opec to expand production. He’s opening new lands for drilling in the Gulf of Mexico and public lands of the US. Right now, what I’m seeing from world leaders, including Biden, is that they’re using the bully pulpit of their position to urge the expansion of fossil fuels. They’ve completely stopped talking about taking climate action.

Shut down fossil fuel production sites early to avoid climate chaos, says study

The effects of the Ukraine war on energy prices offer a golden opportunity for massive investment in renewable energy and phasing out fossil fuels. But the political class doesn’t see it that way…

The leaders of the world are squandering a historic opportunity to make that transition to renewables. Instead, they’re using it as an opportunity to expand the fossil fuel industry, and the fossil fuel CEOs are rubbing their hands in glee at what’s happening right now. They can’t believe their good fortune that Putin invaded Ukraine.

Can you explain the stranglehold that the fossil fuel industry has over the American political system? Sometimes, as an outsider, you see the wildfires on the west coast, you see that Florida is sinking, and it doesn’t make sense…

There’s this kind of equilibrium of corruption that has developed. They know which politicians’ campaigns to support for maximum return on their investment. For them, it’s a tiny investment. Then, somehow they’ve also managed to capture the media. They certainly have the Fox News network on their side, but somehow, even the non-conservative side hasn’t been reporting the story as it should, that this is an emergency for the planet. The public don’t sense any urgency from the media. Therefore, the politicians that are taking these campaign donations from the fossil fuel industry are not being held to account.

It runs deeper doesn’t it? The right to drive wherever and whenever is part of the American dream, any politician who challenges that gets massive pushback. The price of gas or petrol is an emotive issue.

Three-quarters of global heating is caused by burning fossil fuels. Everything else we talk about – planting trees, carbon captures, carbon offsets – is just rearranging deckchairs.

The thing we’ve got to do to avoid hitting the iceberg is to end the fossil fuel industry as quickly as we can. The problem with not protecting the interest of the working class as we make this transition is that they would effectively rise up against any climate policies that made their lives unlivable because of high energy costs. We saw that happen a few years ago with the gilets jaunes [yellow vests] in France.

The only way we can get the working class on board is if the transition away from fossil fuels is effectively subsidised by the ultra rich, which means there does need to be a redistribution of wealth.

You are talking about systematic change leading to a new economic system. When people hear that, they hear “degrowth”. They feel it’s going to impact their standard of living.

People need to understand that all degrowth really is, is a switch in the goal of the economic system. We need to change the goal of the system from the accumulation of capital to the flourishing of all people, not just people in the global north, also people in the global south, and the flourishing of all life on this planet, because our economic system is embedded in the biosphere. If we take down the biosphere, we lose everything, and we don’t have an economic system any more. That’s why we desperately need to change the goal of the system to the flourishing of everyone and all life on the planet.

But many individuals like driving, flying and eating beef. They feel the climate movement wants to take away things they enjoy…

They do. There’s different kinds of pleasure in life, right? Like getting deeply involved in your community, or feeling like you’re involved in something deeply meaningful, like humanity getting on a better course and the future being better for your children.

I would argue that, through my experience, those kinds of pleasures are actually more sustaining. They’re deeply satisfying. They’re less superficial. But yeah, I know that it’s a hard sell. It almost takes a spiritual practice to be able to kind of come out of the addictions of modern life, which are very enticing.

That was the reason that I wrote my book [about reducing his carbon footprint by 90%], because I wanted to get the message out that there’s actually a lot of pleasure in making these kinds of changes. I didn’t know whether it would resonate with people or not. It turned out to resonate with a much smaller fraction of people than I expected.

Is there anyone in American politics that you look to, or a generation of younger representatives who might be able to articulate and sell this kind of vision?

Not really, no, it’s pretty bleak. Bernie Sanders, he’s not young, but he was the closest one that I ever saw to articulating this vision. Just understanding that we’re at risk of losing everything. He would say things like: “I know my climate plan is expensive, but what’s the alternative?”

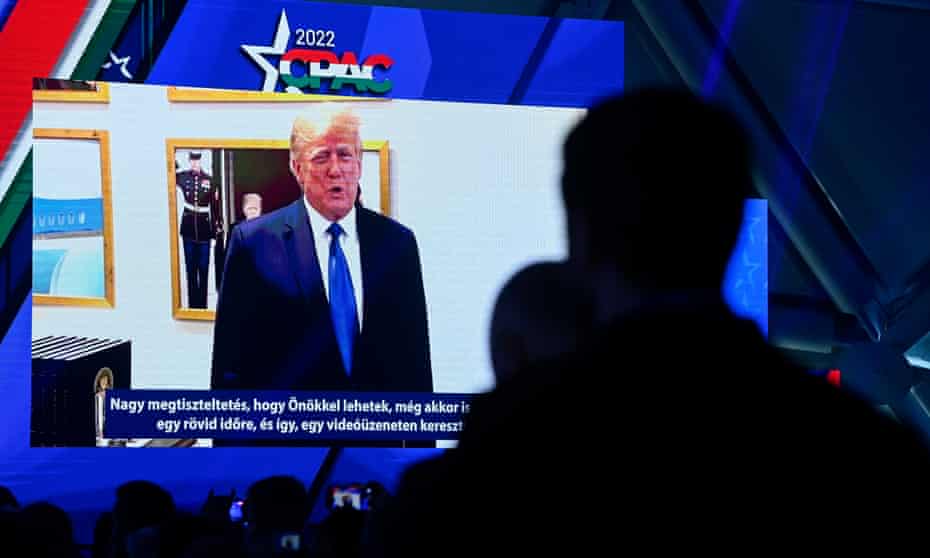

Peter Kalmus and colleague chained to the JP Morgan Chase building, Los Angeles, 6 April this year. Photograph: Brian Emerson

We have to do whatever it takes to save this planet. Because if we degrade the life support systems of this planet, we effectively lose everything. We’re going down this very dangerous slide and we don’t know exactly how far down it takes before we lose X, or before we lose Y, or before this system on the planet breaks down. But we know that the further down we slide, the more we’re going to start going past those sort of collapse points. Bernie Sanders got that. I’ve never seen anything that Joe Biden has said or done to convince me that he understands that. I don’t think he understands what grave danger we’re all in.

Why don’t you run for office, Peter?

We have to do whatever it takes to save this planet. Because if we degrade the life support systems of this planet, we effectively lose everything. We’re going down this very dangerous slide and we don’t know exactly how far down it takes before we lose X, or before we lose Y, or before this system on the planet breaks down. But we know that the further down we slide, the more we’re going to start going past those sort of collapse points. Bernie Sanders got that. I’ve never seen anything that Joe Biden has said or done to convince me that he understands that. I don’t think he understands what grave danger we’re all in.

Why don’t you run for office, Peter?

Then, I’d have to stop being a scientist. There was a new poll where only 42% of Americans thought that climate change was a “very serious problem” – less than half of Americans. That’s a huge problem for electoral politics.

42% – that’s almost a half-full glass. Only a few more percent, you’re in business.

I will say that whichever elected leader makes climate action their top priority and stops the degradation of Earth, they will be remembered by history as one of the most visionary leaders of all time. Nothing could be more clear to me than that.

I do think there’s a way to sell this kind of stuff I’m saying to the American people. Because the jobs that will be created are a tremendous economic opportunity.

There’s an incredible amount of stuff that we need to build, at least initially. We have to build alternative infrastructure, so that we can feed ourselves, and we can clothe ourselves, and we can transport ourselves without fossil fuels.

Do you feel your own mental health is suffering, because you’re so fluent in the data and the politics of global heating?

I’m constantly fending off this sort of ocean of climate anxiety that’s in my brain. When that ocean rises to a high enough level, I can’t really function any more. I get stressed. I am not very fun to be around. My ability to write degrades hugely. The strongest practice I have to keep that ocean of anxiety at bay is a meditation practice, called Vipassana.

Ten ways to confront the climate crisis without losing hope

It takes two hours a day to do this practice. It takes a 10-day silent retreat once a year to kind of build up the batteries. But if I’m doing it, then I have zero climate anxiety. I’m fully aware of the emergency, but it unlocks my ability to be able to do everything I can, to work as hard as I can to sound the alarm, basically.

I used to take vacations in the High Sierra, to kind of recharge through nature, but it doesn’t work any more. Because last summer we took a five-day backpacking trip up there with my younger son and my partner, the three of us. It was too depressing to me, because in the two years that I’d walked on that trail, the John Muir trail, the tree mortality was just outrageous. There were so many dead trees all along the path. Streams and ponds that had once been flowing at that time of year, two years earlier, were bone dry, because of the drought. I can’t go. It’s just too painful for me now. When I’m in the mountains, I’m constantly feeling climate grief. That’s not a way for me to deal with my climate anxiety any more, unfortunately.

Do you understand why some younger people are deciding not to have children, because of the climate crisis?

If I were in their place, I would also choose not to have children. It’s a hard thing to say. It’s so heartbreaking to have this sense that the future is getting worse, and that it’s going to be worse for your kids. Now it feels like it’s getting worse at a very fast rate. One thing I desperately want before I die is to have a feeling that the future is going to be better.

That we’ve switched this corner and we’ve started to change the system towards flourishing for all, and we’ve come out of this madness of billionaires, and fossil fuel, and money in politics. That’s what I want to feel. I’ll feel grief from maybe the loss of the Amazon rainforest, and the loss of most of the world’s coral reefs, but mixed with that grief, I long for a feeling of solidarity. I long to feel a faith in humanity once again, because right now I’m not so sure. There’s some tremendous people out there, but it feels like, as a species, we’re just on autopilot and we’re not making the right decisions. I long to feel that we’re doing things better.