J. Robert Oppenheimer’s early work revolutionized the field of quantum chemistry – and his theory is still used today

The Conversation

August 4, 2023,

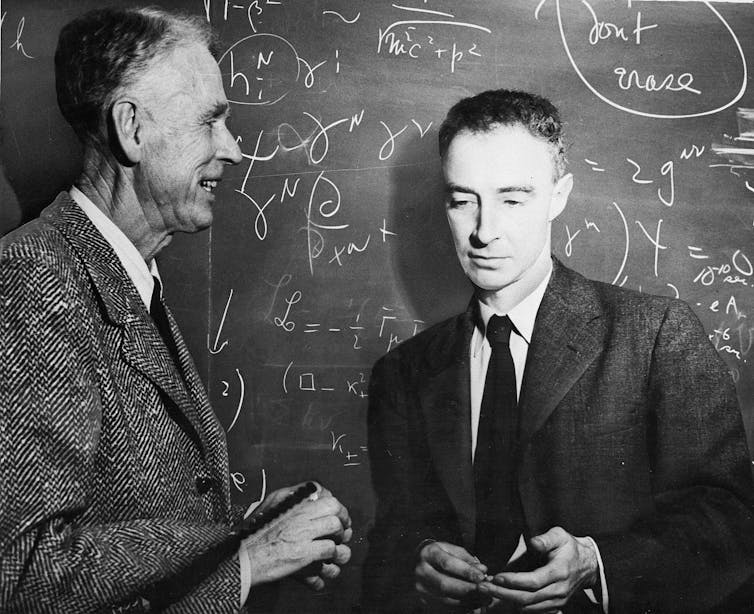

US nuclear physicist Julius Robert Oppenheimer, director of the Los Alamos atomic laboratory, testifying before the Special Senate Committee on Atomic Energy. - Keystone/Getty Images North America/TNS

The release of the film “Oppenheimer,” in July 2023, has renewed interest in the enigmatic scientist J. Robert Oppenheimer’s life. While Oppenheimer will always be recognized as the father of the atomic bomb, his early contributions to quantum mechanics form the bedrock of modern quantum chemistry. His work still informs how scientists think about the structure of molecules today.

Early on in the film, preeminent scientific figures of the time, including Nobel laureates Werner Heisenberg and Ernest Lawrence, compliment the young Oppenheimer on his groundbreaking work on molecules. As a physical chemist, Oppenheimer’s work on molecular quantum mechanics plays a major role in both my teaching and my research.

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation

In 1927, Oppenheimer published a paper called “On the Quantum Theory of Molecules” with his research adviser Max Born. This paper outlined what is commonly referred to as the Born-Oppenheimer approximation. While the name credits both Oppenheimer and his adviser, most historians recognize that the theory is mostly Oppenheimer’s work.

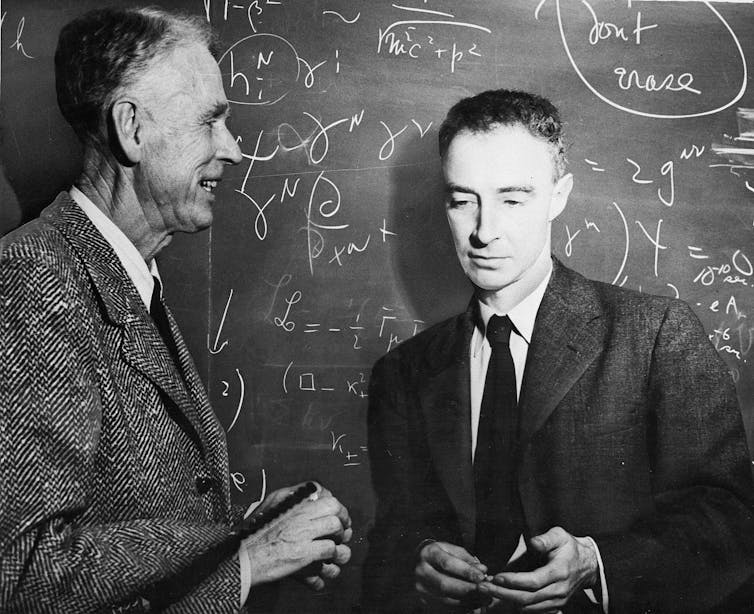

J. Robert Oppenheimer, on the right, in 1947, speaking to mathematician Oswald Veblen at the Princeton Institute for Advance Study. AP/Anonymous

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation offers a way to simplify the complex problem of describing molecules at the atomic level.

Imagine you want to calculate the optimum molecular structure, chemical bonding patterns and physical properties of a molecule using quantum mechanics. You would start by defining the position and motion of all the atomic nuclei and electrons and calculating the important charge attractions and repulsions occurring between these particles in the molecule.

Calculating the properties of molecules gets even more complicated at the quantum level, where particles have wavelike properties and scientists can’t pinpoint their exact position. Instead, particles like electrons must be described by a wave function. A wave function describes the electron’s probability of being in a certain region of space. Determining this wave function and the corresponding energies of the molecule is what is known as solving the molecular Schrödinger equation.

Solving the Schrödinger equation lets scientists calculate the properties of a molecule.

Unfortunately, this equation cannot be solved exactly for even the simplest possible molecule, H₂⁺, which consists of three particles: two hydrogen nuclei (or protons) and one electron.

Oppenheimer’s approach provided a means to obtain an approximate solution. He observed that atomic nuclei are significantly heavier than electrons, with a single proton being nearly 2,000 times more massive than an electron. This means nuclei move much slower than electrons, so scientists can think of them as stationary objects while solving the Schrödinger equation solely for the electrons.

This method reduces the complexity of the calculation and enables scientists to determine the molecule’s wave function with relative ease.

This approximation may seem like a minor adjustment, but the Born-Oppenheimer approximation goes far beyond just simplifying quantum mechanics calculations on molecules. It actually shapes how chemists view molecules and chemical reactions.

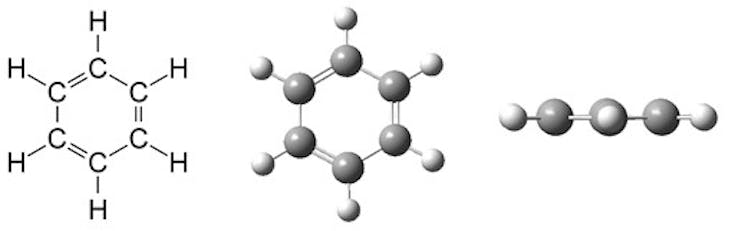

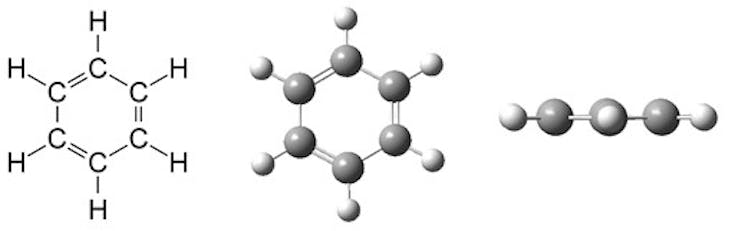

When scientists visualize molecules, we usually think of them as a set of fixed nuclei with shared electrons that move between nuclei. In chemistry class, students typically build “ball-and-stick” models consisting of rigid nuclei (balls) sharing electrons through a bonding framework (sticks). These models are a direct consequence of the Born-Oppenheimer approximation.

The ball-and-stick model shows nuclei represented by spheres – or balls – with shared electron bonds represented by sticks. This image shows the structure of a benzene molecule. Aaron Harrison

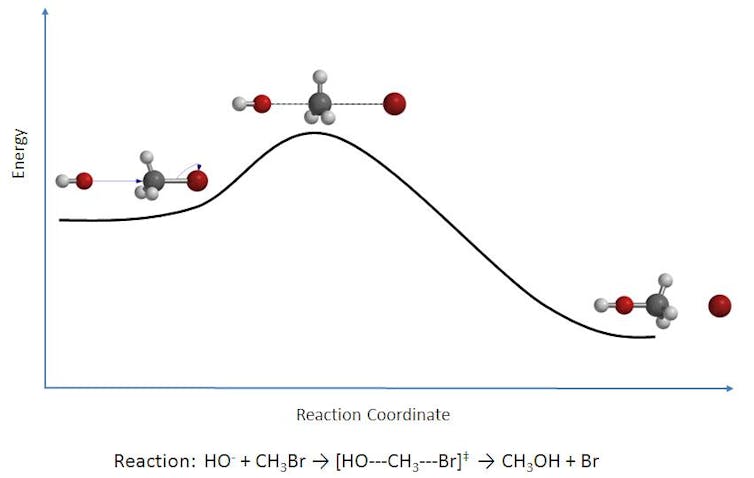

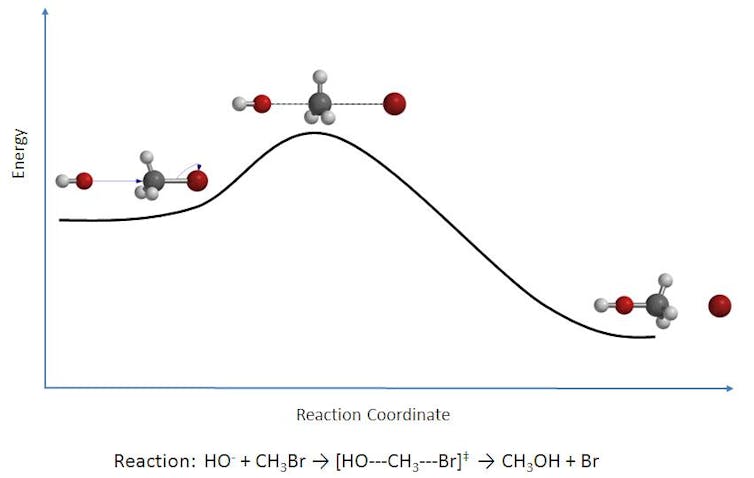

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation also influenced how scientists think about chemical reactions. During a chemical reaction, atomic nuclei are not stationary; they rearrange and move. Electron interactions guide the nuclei’s movements by forming an energy surface, which the nuclei can move on throughout the reaction. In this way, electrons drive the molecule’s progression through a chemical reaction. Oppenheimer demonstrated that the way electrons behave is the essence of chemistry as a science.

Molecules can change structure during a chemical reaction.

The Conversation

August 4, 2023,

US nuclear physicist Julius Robert Oppenheimer, director of the Los Alamos atomic laboratory, testifying before the Special Senate Committee on Atomic Energy. - Keystone/Getty Images North America/TNS

The release of the film “Oppenheimer,” in July 2023, has renewed interest in the enigmatic scientist J. Robert Oppenheimer’s life. While Oppenheimer will always be recognized as the father of the atomic bomb, his early contributions to quantum mechanics form the bedrock of modern quantum chemistry. His work still informs how scientists think about the structure of molecules today.

Early on in the film, preeminent scientific figures of the time, including Nobel laureates Werner Heisenberg and Ernest Lawrence, compliment the young Oppenheimer on his groundbreaking work on molecules. As a physical chemist, Oppenheimer’s work on molecular quantum mechanics plays a major role in both my teaching and my research.

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation

In 1927, Oppenheimer published a paper called “On the Quantum Theory of Molecules” with his research adviser Max Born. This paper outlined what is commonly referred to as the Born-Oppenheimer approximation. While the name credits both Oppenheimer and his adviser, most historians recognize that the theory is mostly Oppenheimer’s work.

J. Robert Oppenheimer, on the right, in 1947, speaking to mathematician Oswald Veblen at the Princeton Institute for Advance Study. AP/Anonymous

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation offers a way to simplify the complex problem of describing molecules at the atomic level.

Imagine you want to calculate the optimum molecular structure, chemical bonding patterns and physical properties of a molecule using quantum mechanics. You would start by defining the position and motion of all the atomic nuclei and electrons and calculating the important charge attractions and repulsions occurring between these particles in the molecule.

Calculating the properties of molecules gets even more complicated at the quantum level, where particles have wavelike properties and scientists can’t pinpoint their exact position. Instead, particles like electrons must be described by a wave function. A wave function describes the electron’s probability of being in a certain region of space. Determining this wave function and the corresponding energies of the molecule is what is known as solving the molecular Schrödinger equation.

Solving the Schrödinger equation lets scientists calculate the properties of a molecule.

Unfortunately, this equation cannot be solved exactly for even the simplest possible molecule, H₂⁺, which consists of three particles: two hydrogen nuclei (or protons) and one electron.

Oppenheimer’s approach provided a means to obtain an approximate solution. He observed that atomic nuclei are significantly heavier than electrons, with a single proton being nearly 2,000 times more massive than an electron. This means nuclei move much slower than electrons, so scientists can think of them as stationary objects while solving the Schrödinger equation solely for the electrons.

This method reduces the complexity of the calculation and enables scientists to determine the molecule’s wave function with relative ease.

This approximation may seem like a minor adjustment, but the Born-Oppenheimer approximation goes far beyond just simplifying quantum mechanics calculations on molecules. It actually shapes how chemists view molecules and chemical reactions.

When scientists visualize molecules, we usually think of them as a set of fixed nuclei with shared electrons that move between nuclei. In chemistry class, students typically build “ball-and-stick” models consisting of rigid nuclei (balls) sharing electrons through a bonding framework (sticks). These models are a direct consequence of the Born-Oppenheimer approximation.

The ball-and-stick model shows nuclei represented by spheres – or balls – with shared electron bonds represented by sticks. This image shows the structure of a benzene molecule. Aaron Harrison

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation also influenced how scientists think about chemical reactions. During a chemical reaction, atomic nuclei are not stationary; they rearrange and move. Electron interactions guide the nuclei’s movements by forming an energy surface, which the nuclei can move on throughout the reaction. In this way, electrons drive the molecule’s progression through a chemical reaction. Oppenheimer demonstrated that the way electrons behave is the essence of chemistry as a science.

Molecules can change structure during a chemical reaction.

Computational quantum chemistry

In the century since the publication of the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, scientists have vastly improved their ability to calculate the chemical structure and reactivity of molecules.

This field, known as computational quantum chemistry, has grown exponentially with the widespread availability of faster, more powerful high-end computational resources. Currently, chemists use computational quantum chemistry for various applications ranging from discovering novel pharmaceuticals to designing better photovoltaics before ever trying to produce them in the lab. At the core of much of this field of research is the Born-Oppenheimer approximation.

Despite its many uses, the Born-Oppenheimer approximation isn’t perfect. For example, the approximation often breaks down in light-driven chemical reactions, such as in the chemical reaction that allows animals to see light. Chemists are investigating workarounds for these cases. Nevertheless, the application of quantum chemistry made possible by the Born-Oppenheimer approximation will continue to expand and improve.

In the future, a new era of quantum computers could make computational quantum chemistry even more robust by performing faster computations on increasingly large molecular systems.

Aaron W. Harrison, Assistant Professor of Chemistry, Austin College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

In the century since the publication of the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, scientists have vastly improved their ability to calculate the chemical structure and reactivity of molecules.

This field, known as computational quantum chemistry, has grown exponentially with the widespread availability of faster, more powerful high-end computational resources. Currently, chemists use computational quantum chemistry for various applications ranging from discovering novel pharmaceuticals to designing better photovoltaics before ever trying to produce them in the lab. At the core of much of this field of research is the Born-Oppenheimer approximation.

Despite its many uses, the Born-Oppenheimer approximation isn’t perfect. For example, the approximation often breaks down in light-driven chemical reactions, such as in the chemical reaction that allows animals to see light. Chemists are investigating workarounds for these cases. Nevertheless, the application of quantum chemistry made possible by the Born-Oppenheimer approximation will continue to expand and improve.

In the future, a new era of quantum computers could make computational quantum chemistry even more robust by performing faster computations on increasingly large molecular systems.

Aaron W. Harrison, Assistant Professor of Chemistry, Austin College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

A volunteer holds plastic straws picked during the World Clean-Up day activity in Kendari, Indonesia. Andry Denisah / SOPA Images / LightRocket via Getty Images

A volunteer holds plastic straws picked during the World Clean-Up day activity in Kendari, Indonesia. Andry Denisah / SOPA Images / LightRocket via Getty Images