Jailed Iranian activist Narges Mohammadi wins the Nobel Peace Prize for fighting women's oppression© Provided by The Canadian Press

OSLO — Imprisoned Iranian activist Narges Mohammadi won the Nobel Peace Prize on Friday in recognition of her tireless campaigning for women’s rights and democracy, and against the death penalty.

Mohammadi, 51, has kept up her activism despite numerous arrests by Iranian authorities and spending years behind bars. She has remained a leading light for nationwide, women-led protests sparked by the death last year of a 22-year-old woman in police custody that have grown into one of the most intense challenges to Iran’s theocratic government.

Berit Reiss-Andersen, the chair of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, began Friday's announcement with the words “Woman, Life, Freedom” in Farsi — the slogan of the demonstrations in Iran.

“This prize is first and foremost a recognition of the very important work of a whole movement in Iran with its undisputed leader, Narges Mohammadi," Reiss-Andersen said. She also urged Iran to release Mohammadi in time for the prize ceremony on Dec. 10.

For nearly all of Mohammadi’s life, Iran has been governed by a Shiite theocracy headed by the country’s supreme leader. While women hold jobs, academic positions and even government appointments, their lives are tightly controlled. Women are required by law to wear a headscarf, or hijab, to cover their hair. Iran and neighboring Afghanistan remain the only countries to mandate that.

In a statement released after the Nobel announcement, Mohammadi said she will "never stop striving for the realization of democracy, freedom and equality.”

“Surely, the Nobel Peace Prize will make me more resilient, determined, hopeful and enthusiastic on this path, and it will accelerate my pace," she said in the statement, prepared in advance in case she was named the Nobel laureate.

An engineer by training, Mohammadi has been imprisoned 13 times and convicted five. In total, she has been sentenced to 31 years in prison. Her most recent incarceration began when she was detained in 2021 after attending a memorial for a person killed in nationwide protests.

She has been held at Tehran’s notorious Evin Prison, whose inmates include those with Western ties and political prisoners.

U.S. President Joe Biden and Amnesty International joined calls for Mohammadi’s immediate release.

“This award is a recognition that, even as she is currently and unjustly held in Evin Prison, the world still hears the clarion voice of Narges Mohammadi calling for freedom and equality,” Biden said in a statement. “I urge the government in Iran to immediately release her and her fellow gender equality advocates from captivity.”

Friday's prize sends "a clear message to the Iranian authorities that their crackdown on peaceful critics and human rights defenders will not go unchallenged,” Amnesty said.

Mohammadi's brother, Hamidreza Mohammadi, said that while “the prize means that the world has seen this movement,” it will not affect the situation in Iran.

“The regime will double down on the opposition" he told The Associated Press. "They will just crush people.”

Mohammadi's husband, Taghi Rahmani, who lives in exile in Paris with their two children, 16-year-old twins, said his wife "has a sentence she always repeats: ‘Every single award will make me more intrepid, more resilient and more brave for realizing human rights, freedom, civil equality and democracy.'”

Rahmani hasn't been able to see his wife for 11 years, and their children haven't seen their mother for seven, he said.

Their son, Ali Rahmani, said the Nobel was not just for his mother: "It's for the struggle."

"This prize is for the entire population, for the whole struggle from the beginning, since the Islamic government came to power," the teen said.

Women political prisoners in Evin aren’t allowed to use the phone on Thursday and Friday, so Mohammadi prepared her statement in advance of the Nobel announcement, said exiled Iranian photographer Reihane Taravati, a family friend who spent 14 days in solitary confinement there before fleeing to France this year.

Mohammadi is the 19th woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize and the second Iranian woman, after human rights activist Shirin Ebadi won in 2003.

U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres called Friday's selection “a tribute to all those women who are fighting for their rights at the risk of their freedom, their health and even their lives.”

It’s the fifth time in its 122-year history that the Nobel Peace Prize has been given to someone in prison or under house arrest. In 2022, the top human rights advocate in Belarus, Ales Bialiatski, was among the winners. He remains imprisoned.

Mohammadi was in detention for the recent protests of the death of Mahsa Amini, who was picked up by the morality police for her allegedly loose headscarf. More than 500 people were killed in a security crackdown, while over 22,000 others were arrested.

But from behind bars, Mohammadi contributed an opinion piece for The New York Times in September. “What the government may not understand is that the more of us they lock up, the stronger we become,” she wrote.

Iran's government, which holds Mohammadi behind bars, criticized the Nobel committee's decision as being part of the “interventionist and anti-Iranian policies of some European countries.”

It “is another link in the chain of pressure from Western circles against Iran,” Iranian Foreign Ministry spokesperson Nasser Kanaani said in a statement. Iranian state media described Mohammadi as being “in and out of jail for much of her adult life," calling her internationally applauded activism “propaganda” and an “act against national security.”

In Tehran, people expressed support for Mohammadi and her resilience.

"The prize was her right. She stayed inside the country, in prison and defended people, bravo!" said Mina Gilani, a girl's high school teacher.

Arezou Mohebi, a 22-year-old chemistry student, called the Nobel “an award for all Iranian girls and women,” and described Mohammadi "as the bravest I have ever seen."

Political analyst Ahmad Zeidabadi said the prize might lead to more pressure on Mohammadi.

“The prize will simultaneously bring possibilities and restrictions,” he wrote online. “I hope Narges will not be confined by its restrictions.”

Before being jailed, Mohammadi was vice president of the banned Defenders of Human Rights Center in Iran, founded by Nobel laureate Ebadi.

The Nobel prizes carry a cash award of 11 million Swedish kronor ($1 million). Unlike the other Nobel prizes that are selected and announced in Stockholm, founder Alfred Nobel decreed the peace prize be decided and awarded in Oslo by the five-member Norwegian Nobel Committee.

The Nobel season ends Monday with the announcement of the winner of the economics prize, formally known as the Bank of Sweden Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel.

___

Gambrell reported from Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Leicester reported from LePecq, France and Becatoros from Athens, Greece. Mike Corder at The Hague, Netherlands, Nicolas Garriga in Paris and Jan M. Olsen in Copenhagen, Denmark, contributed.

___

Follow all AP stories about the Nobel Prizes at https://apnews.com/hub/nobel-prizes

Jon Gambrell, John Leicester And Elena Becatoros, The Associated Press

Cécile FEUILLATRE and Stuart WILLIAMS

Fri, 6 October 2023

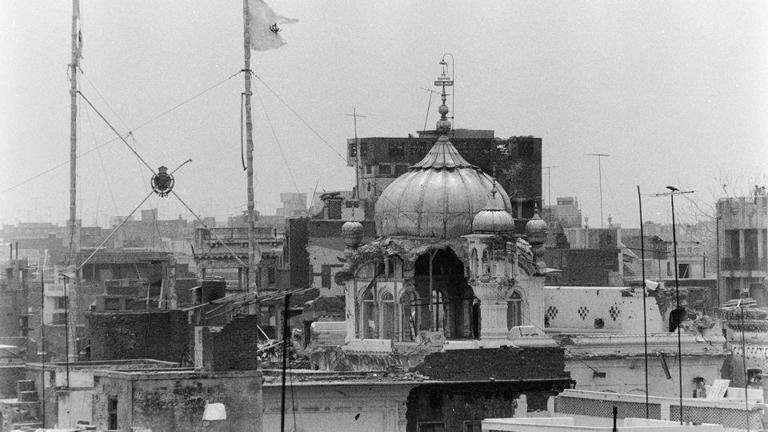

Mohammadi is held in Tehran's Evin prison which was hit by a fire in October

Rights campaigner and 2023 Nobel Peace laureate Narges Mohammadi said in a September interview with AFP that she retained hope for change in Iran, despite having no prospect of release from prison and enduring the pain of separation from her family.

In the interview, where Mohammadi gave written answers to AFP from Evin prison in Tehran, she insisted the protest movement that erupted one year ago in Iran against the Islamic republic is still alive.

First arrested 22 years ago, Mohammadi, 51, has spent much of the past two decades in and out of jail over her unstinting campaigning for human rights in Iran. She has most recently been incarcerated since November 2021 and has not seen her children for eight years.

While she could only witness from behind bars the protests that broke out following the death on September 16, 2022 of Mahsa Amini -- who had been arrested for violating Iran's strict dress rules for women -- she said the movement made clear the levels of dissatisfaction in society.

"The government was not able to break the protests of the people of Iran and I believe that society has achieved things that have weakened the foundations of religious-authoritarian rule," she told AFP.

Noting that Iran had even before September 2022 seen repeated protest outbreaks, she added: "We have seen cycles of protests in recent years and this shows the irreversible nature of the situation and the scope for the expansion of the protests."

- 'Realising democracy' -

She said that after "44 years of oppression, discrimination and continuous repression of the government against women in public and personal life" the protests had "accelerated the process of realising democracy, freedom and equality in Iran".

Mohammadi said the protests opposing the Islamic republic had involved people "beyond urban areas and educated classes" at a time when religious authority was "losing its place" in society.

"The weakening of the religious element has created a vacuum that the government has not been able to fill with other economic and social factors, as the government is essentially ineffective and corrupt."

But she was bitterly critical of what she described as the "appeasement" by the West of Iran's leaders, saying foreign governments "have not recognised the progressive forces and leaders in Iran and pursued policies aimed at perpetuating the religious-authoritarian system in Iran."

Mohammadi said she was currently serving a combined sentence of 10 years and nine months in prison, had also been sentenced to 154 lashes and had five cases against her linked to her activities in jail alone.

"I have almost no prospect of freedom," she said.

- 'Indescribable suffering' -

But she said she "kept the hope of seeing the light of freedom and hearing its voice" and in prison organised discussions in the women's wing of Evin as well as singing and even dancing.

"Prison has always been at the core of opposition, resistance and struggle in my country and for me it also embodies the essence of life in all its beauty."

"The Evin women's wing is one of the most active, resistant and joyful quarters of political prisoners in Iran. During my years in prison, on three occasions, I shared detention with at least 600 women, and I am proud of each of them."

But for Mohammadi, the cost of her activism has also been immense, meaning she has missed much of the childhood of her twin children Kiana and Ali who now live, along with her husband Taghi Rahmani, in France.

As well as not seeing them for eight years, restrictions placed by the prison on her telephone calls mean she has not even heard their voices for more than a year and a half.

"My most incurable and indescribable suffering is the longing to be with my children from whose lives I departed when they were eight."

"The price of the struggle is not only torture and prison, it is a heart that breaks with every regret and a pain that strikes to the marrow of your bones."

But she added: "I believe that as long as democracy, equality and freedom have not been achieved, we must continue to fight and sacrifice."

cf-nzg-sjw/jm

.jpg)

Global News

Global News