Empire Decline and Costly Delusions

MARCH 8, 2024

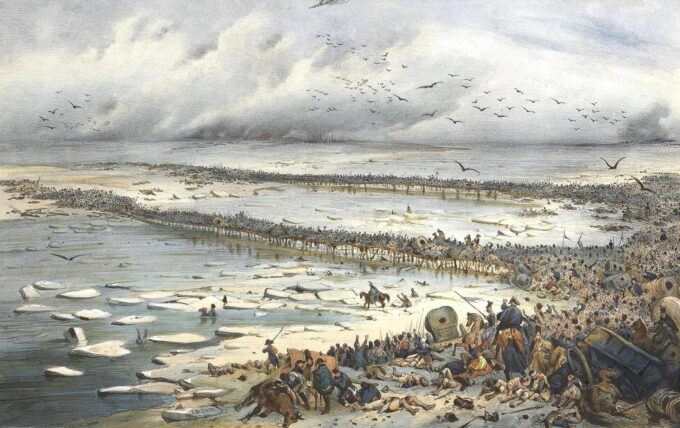

Пераправа цераз раку Бярэзіну (Biarezina)

When Napoleon engaged Russia in a European land war, the Russians mounted a determined defense, and the French lost. When Hitler tried the same, the Soviet Union responded similarly, and the Germans lost. In World War 1 and its post-revolutionary civil war (1914-1922), first Russia and then the USSR defended with far greater effect against two invasions than the invaders had calculated. That history ought to have cautioned U.S. and European leaders to minimize the risks of confronting Russia, especially when Russia felt threatened and determined to defend itself.

Instead of caution, delusions prompted ill-advised judgments by the collective West (roughly the G7 nations: the U.S. and its major allies). Those delusions emerged partly from the collective West’s widespread denial of its relative economic decline in the 21st century. That denial also enabled a remarkable blindness to the limits that decline imposed on the collective West’s global actions. Delusions also flowed from a basic undervaluation of Russia’s defensiveness and its resulting commitments. The Ukraine war starkly illustrates both the decline and the costly delusions it fosters.

The United States and Europe seriously underestimated what Russia could and would do to prevail militarily in Ukraine. Russia’s victory—at least so far after two years of war—has proven decisive. Their underestimation stemmed from a shared inability to grasp or absorb the changing world economy and its implications. By mostly minimizing, marginalizing, or simply denying the decline of the U.S. empire relative to the rise of China and its BRICS allies, the United States and Europe missed that decline’s unfolding implications. Russia’s allies’ support combined with its national determination to defend itself have so far defeated a Ukraine heavily funded and armed by the collective West. Historically, declining empires often provoke denials and delusions that teach their people “hard lessons” and impose on them “hard choices”. That is where we are now.

The economics of the U.S. empire decline constitutes the continuing global context. The BRICS countries’ collective GDP, wealth, income, share of world trade, and presence at the highest levels of new technology increasingly exceed those of the G7. That relentless economic development frames the decline of the G7’s political and cultural influences as well. The massive U.S. and European sanctions program against Russia after February 2022 has failed. Russia turned especially to its BRICS allies to quickly as well as comprehensively escape most of those sanctions’ intended effects.

UN votes on the ceasefire issue in Gaza reflect and reinforce the mounting difficulties facing the U.S. position in the Middle East and globally. So does the Houthis’ intervention in Red Sea shipping and so too will other future Arab and Islamic initiatives supporting Palestine against Israel. Among the consequences flowing from the changing world economy, many work to undermine and weaken the U.S. empire.

Trump’s disrespect for NATO is partly an expression of disappointment with an institution he can blame for failing to stop empire’s decline. Trump and his supporters broadly downgrade many institutions once thought crucially central to running the U.S., empire globally. Both the Trump and Biden regimes attacked China’s Huawei corporation, shared commitments to trade and tariff wars, and heavily subsidized competitively challenged U.S. corporations. Nothing less than a historic shift away from neoliberal globalization toward economic nationalism is underway. An American empire that once targeted the whole world is shrinking into a merely regional bloc confronting one or more emerging regional blocs. Much of the rest of the world’s nations—a possible “world majority” of the planet’s people—are pulling away from the U.S. empire.

U.S. leaders’ aggressive economic nationalist policies distract attention from the empire’s decline and thereby facilitate its denial. Yet they also cause new problems. Allies fear that economic nationalism in the United States already has or will soon adversely affect their economic relations with the United States; “America first” targets not only the Chinese. Many countries are rethinking and reconstructing their economic relations with the United States and their expectations about those relations’ futures. Likewise, major groups of U.S. employers are reconsidering their investment strategies. Those who invested heavily overseas as part of the neoliberal globalization frenzies of the last half century are especially fearful. They anticipate costs and losses from policy shifts toward economic nationalism. Their pushback slows those shifts. As capitalists everywhere adjust practically to the changing world economy, they also quarrel and dispute the direction and pace of change. That injects more uncertainty and volatility into a thereby further destabilized world economy. As the U.S. empire unravels, the world economic order it once dominated and enforced likewise changes.

“Make America Great Again” (MAGA) slogans have politically weaponized U.S. empire’s decline, always in carefully vague and general terms. They simplify and misunderstand it within another set of delusions. Trump will, he promises repeatedly, undo that decline and reverse it. He will punish those he blames for it: China, but also Democrats, liberals, globalists, socialists, and Marxists whom he lumps together in a bloc-building strategy. There is rarely any serious attention to the economics of the G7’s decline since to do so would critically implicate capitalists’ profit-driven decisions as key causes of the decline. Neither Republicans nor Democrats dare do that. Biden speaks and acts as if the U.S. wealth and power positions within the world economy were undiminished from what they were across the second half of the 20th century (most of Biden’s political lifetime).

Continuing to fund and arm Ukraine in the war with Russia, like endorsing and supporting Israel’s treatment of Palestinians, are policies premised on denials of a changed world. So too are successive waves of economic sanctions despite each wave failing to achieve its goals. Using tariffs to keep better, cheaper Chinese electric vehicles off the U.S. market will only disadvantage U.S. individuals (via such Chinese electric vehicles’ higher prices) and businesses (via global competition from businesses buying the cheaper Chinese cars and trucks).

Perhaps the greatest, costliest delusions that follow from a denial of years of decline dog the upcoming presidential election. The two major parties and their candidates offer no serious plan for how to deal with the declining empire they seek to lead. Both parties took turns presiding over the decline, yet denial and blaming the other is all either party offers in 2024. Biden offers voters a partnership in denial that the empire is declining. Trump promises vaguely to undo the decline caused by bad Democratic leadership that his election will remove. Nothing either major party does entails sober admissions and assessments of a changed world economy and how each plans to cope with that.

The last 40 to 50 years of the economic history of the G7 witnessed extreme redistributions of wealth and income upward. Those redistributions functioned as both causes and effects of neoliberal globalization. However, domestic reactions (economic and social divisions increasingly hostile and volatile) and foreign reactions (emergence of today’s China and BRICS) are undermining neoliberal globalization and beginning to challenge its accompanying inequalities. U.S. capitalism and its empire cannot yet face its decline amid a changing world. Delusions about retaining or regaining power at the top of society proliferate alongside delusional conspiracy theories and political scapegoating (immigrants, China, Russia) below.

Meanwhile, the economic, political, and cultural costs mount. And on some level, as per Leonard Cohen’s famous song, “Everybody Knows.”

This article was produced by Economy for All, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

By Alfred Mccoy

Image by TSgt Bill Kimble, Public domain

Empires don’t just fall like toppled trees. Instead, they weaken slowly as a succession of crises drain their strength and confidence until they suddenly begin to disintegrate. So it was with the British, French, and Soviet empires; so it now is with imperial America.

Great Britain confronted serious colonial crises in India, Iran, and Palestine before plunging headlong into the Suez Canal and imperial collapse in 1956. In the later years of the Cold War, the Soviet Union faced its own challenges in Czechoslovakia, Egypt, and Ethiopia before crashing into a brick wall in its war in Afghanistan.

America’s post-Cold War victory lap suffered its own crisis early in this century with disastrous invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. Now, looming just over history’s horizon are three more imperial crises in Gaza, Taiwan, and Ukraine that could cumulatively turn a slow imperial recessional into an all-too-rapid decline, if not collapse.

As a start, let’s put the very idea of an imperial crisis in perspective. The history of every empire, ancient or modern, has always involved a succession of crises — usually mastered in the empire’s earlier years, only to be ever more disastrously mishandled in its era of decline. Right after World War II, when the United States became history’s most powerful empire, Washington’s leaders skillfully handled just such crises in Greece, Berlin, Italy, and France, and somewhat less skillfully but not disastrously in a Korean War that never quite officially ended. Even after the dual disasters of a bungled covert invasion of Cuba in 1961 and a conventional war in Vietnam that went all too disastrously awry in the 1960s and early 1970s, Washington proved capable of recalibrating effectively enough to outlast the Soviet Union, “win” the Cold War, and become the “lone superpower” on this planet.

In both success and failure, crisis management usually entails a delicate balance between domestic politics and global geopolitics. President John F. Kennedy’s White House, manipulated by the CIA into the disastrous 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba, managed to recover its political balance sufficiently to check the Pentagon and achieve a diplomatic resolution of the dangerous 1962 Cuban missile crisis with the Soviet Union.

America’s current plight, however, can be traced at least in part to a growing imbalance between a domestic politics that appears to be coming apart at the seams and a series of challenging global upheavals. Whether in Gaza, Ukraine, or even Taiwan, the Washington of President Joe Biden is clearly failing to align domestic political constituencies with the empire’s international interests. And in each case, crisis mismanagement has only been compounded by errors that have accumulated in the decades since the Cold War’s end, turning each crisis into a conundrum without an easy resolution or perhaps any resolution at all. Both individually and collectively, then, the mishandling of these crises is likely to prove a significant marker of America’s ultimate decline as a global power, both at home and abroad.

Creeping Disaster in Ukraine

Since the closing months of the Cold War, mismanaging relations with Ukraine has been a curiously bipartisan project. As the Soviet Union began breaking up in 1991, Washington focused on ensuring that Moscow’s arsenal of possibly 45,000 nuclear warheads was secure, particularly the 5,000 atomic weapons then stored in Ukraine, which also had the largest Soviet nuclear weapons plant at Dnipropetrovsk.

During an August 1991 visit, President George H.W. Bush told Ukrainian Prime Minister Leonid Kravchuk that he could not support Ukraine’s future independence and gave what became known as his “chicken Kiev” speech, saying: “Americans will not support those who seek independence in order to replace a far-off tyranny with a local despotism. They will not aid those who promote a suicidal nationalism based upon ethnic hatred.” He would, however, soon recognize Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia as independent states since they didn’t have nuclear weapons.

When the Soviet Union finally imploded in December 1991, Ukraine instantly became the world’s third-largest nuclear power, though it had no way to actually deliver most of those atomic weapons. To persuade Ukraine to transfer its nuclear warheads to Moscow, Washington launched three years of multilateral negotiations, while giving Kyiv “assurances” (but not “guarantees”) of its future security — the diplomatic equivalent of a personal check drawn on a bank account with a zero balance.

Under the Budapest Memorandum on Security in December 1994, three former Soviet republics — Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine — signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and started transferring their atomic weapons to Russia. Simultaneously, Russia, the U.S., and Great Britain agreed to respect the sovereignty of the three signatories and refrain from using such weaponry against them. Everyone present, however, seemed to understand that the agreement was, at best, tenuous. (One Ukrainian diplomat told the Americans that he had “no illusions that the Russians would live up to the agreements they signed.”)

Meanwhile — and this should sound familiar today — Russian President Boris Yeltsin raged against Washington’s plans to expand NATO further, accusing President Bill Clinton of moving from a Cold War to a “cold peace.” Right after that conference, Defense Secretary William Perry warned Clinton, point blank, that “a wounded Moscow would lash out in response to NATO expansion.”

Nonetheless, once those former Soviet republics were safely disarmed of their nuclear weapons, Clinton agreed to begin admitting new members to NATO, launching a relentless eastward march toward Russia that continued under his successor George W. Bush. It came to include three former Soviet satellites, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland (1999); three one-time Soviet Republics, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania (2004); and three more former satellites, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia (2004). At the Bucharest summit in 2008, moreover, the alliance’s 26 members unanimously agreed that, at some unspecified point, Ukraine and Georgia, too, would “become members of NATO.” In other words, having pushed NATO right up to the Ukrainian border, Washington seemed oblivious to the possibility that Russia might feel in any way threatened and react by annexing that nation to create its own security corridor.

In those years, Washington also came to believe that it could transform Russia into a functioning democracy to be fully integrated into a still-developing American world order. Yet for more than 200 years, Russia’s governance had been autocratic and every ruler from Catherine the Great to Leonid Brezhnev had achieved domestic stability through incessant foreign expansion. So, it should hardly have been surprising when the seemingly endless expansion of NATO led Russia’s latest autocrat, Vladimir Putin, to invade the Crimean Peninsula in March 2014, only weeks after hosting the Winter Olympics.

In an interview soon after Moscow annexed that area of Ukraine, President Obama recognized the geopolitical reality that could yet consign all of that land to Russia’s orbit, saying: “The fact is that Ukraine, which is a non-NATO country, is going to be vulnerable to military domination by Russia no matter what we do.”

Then, in February 2022, after years of low-intensity fighting in the Donbass region of eastern Ukraine, Putin sent 200,000 mechanized troops to capture the country’s capital, Kyiv, and establish that very “military domination.” At first, as the Ukrainians surprisingly fought off the Russians, Washington and the West reacted with a striking resolve — cutting Europe’s energy imports from Russia, imposing serious sanctions on Moscow, expanding NATO to all of Scandinavia, and dispatching an impressive arsenal of armaments to Ukraine.

After two years of never-ending war, however, cracks have appeared in the anti-Russian coalition, indicating that Washington’s global clout has declined markedly since its Cold War glory days. After 30 years of free-market growth, Russia’s resilient economy has weathered sanctions, its oil exports have found new markets, and its gross domestic product is projected to grow a healthy 2.6% this year. In last spring and summer’s fighting season, a Ukrainian “counteroffensive” failed and the war is, in the view of both Russian and Ukrainian commanders, at least “stalemated,” if not now beginning to turn in Russia’s favor.

Most critically, U.S. support for Ukraine is faltering. After successfully rallying the NATO alliance to stand with Ukraine, the Biden White House opened the American arsenal to provide Kyiv with a stunning array of weaponry, totaling $46 billion, that gave its smaller army a technological edge on the battlefield. But now, in a move with historic implications, part of the Republican (or rather Trumpublican) Party has broken with the bipartisan foreign policy that sustained American global power since the Cold War began. For weeks, the Republican-led House has even repeatedly refused to consider President Biden’s latest $60 billion aid package for Ukraine, contributing to Kyiv’s recent reverses on the battlefield.

The Republican Party’s rupture starts with its leader. In the view of former White House adviser Fiona Hill, Donald Trump was so painfully deferential to Vladimir Putin during “the now legendarily disastrous press conference” at Helsinki in 2018 that critics were convinced “the Kremlin held sway over the American president.” But the problem goes so much deeper. As New York Times columnist David Brooks noted recently, the Republican Party’s historic “isolationism is still on the march.” Indeed, between March 2022 and December 2023, the Pew Research Center found that the percentage of Republicans who think the U.S. gives “too much support” to Ukraine climbed from just 9% to a whopping 48%. Asked to explain the trend, Brooks feels that “Trumpian populism does represent some very legitimate values: the fear of imperial overreach… [and] the need to protect working-class wages from the pressures of globalization.”

Since Trump represents this deeper trend, his hostility toward NATO has taken on an added significance. His recent remarks that he would encourage Russia to “do whatever the hell they want” to a NATO ally that didn’t pay its fair share sent shockwaves across Europe, forcing key allies to consider what such an alliance would be like without the United States (even as Russian President Vladimir Putin, undoubtedly sensing a weakening of U.S. resolve, threatened Europe with nuclear war). All of this is certainly signaling to the world that Washington’s global leadership is now anything but a certainty.

Crisis in Gaza

Just as in Ukraine, decades of diffident American leadership, compounded by increasingly chaotic domestic politics, let the Gaza crisis spin out of control. At the close of the Cold War, when the Middle East was momentarily disentangled from great-power politics, Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization signed the 1993 Oslo Accord. In it, they agreed to create the Palestinian Authority as the first step toward a two-state solution. For the next two decades, however, Washington’s ineffectual initiatives failed to break the deadlock between that Authority and successive Israeli governments that prevented any progress toward such a solution.

In 2005, Israel’s hawkish Prime Minister Ariel Sharon decided to withdraw his defense forces and 25 Israeli settlements from the Gaza Strip with the aim of improving “Israel’s security and international status.” Within two years, however, Hamas militants had seized power in Gaza, ousting the Palestinian Authority under President Mahmoud Abbas. In 2009, the controversial Benjamin Netanyahu started his nearly continuous 15-year stretch as Israel’s prime minister and soon discovered the utility of supporting Hamas as a political foil to block the two-state solution he so abhorred.

Not surprisingly then, the day after last year’s tragic October 7th Hamas attack, theTimes of Israel published this headline: “For Years Netanyahu Propped Up Hamas. Now It’s Blown Up in Our Faces.” In her lead piece, senior political correspondent Tal Schneider reported: “For years, the various governments led by Benjamin Netanyahu took an approach that divided power between the Gaza Strip and the West Bank — bringing Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas to his knees while making moves that propped up the Hamas terror group.”

On October 18th, with the Israeli bombing of Gaza already inflicting severe casualties on Palestinian civilians, President Biden flew to Tel Aviv for a meeting with Netanyahu that would prove eerily reminiscent of Trump’s Helsinki press conference with Putin. After Netanyahu praised the president for drawing “a clear line between the forces of civilization and the forces of barbarism,” Biden endorsed that Manichean view by condemning Hamas for “evils and atrocities that make ISIS look somewhat more rational” and promised to provide the weaponry Israel needed “as they respond to these attacks.” Biden said nothing about Netanyahu’s previous arm’s length alliance with Hamas or the two-state solution. Instead, the Biden White House began vetoing ceasefire proposals at the U.N. while air-freighting, among other weaponry, 15,000 bombs to Israel, including the behemoth 2,000-pound “bunker busters” that were soon flattening Gaza’s high-rise buildings with increasingly heavy civilian casualties.

After five months of arms shipments to Israel, three U.N. ceasefire vetoes, and nothing to stop Netanyahu’s plan for an endless occupation of Gaza instead of a two-state solution, Biden has damaged American diplomatic leadership in the Middle East and much of the world. In November and again in February, massive crowds calling for peace in Gaza marched in Berlin, London, Madrid, Milan, Paris, Istanbul, and Dakar, among other places.

Moreover, the relentless rise in civilian deaths well past 30,000 in Gaza, striking numbers of them children, has already weakened Biden’s domestic support in constituencies that were critical for his win in 2020 — including Arab-Americans in the key swing state of Michigan, African-Americans nationwide, and younger voters more generally. To heal the breach, Biden is now becoming desperate for a negotiated cease-fire. In an inept intertwining of international and domestic politics, the president has given Netanyahu, a natural ally of Donald Trump, the opportunity for an October surprise of more devastation in Gaza that could rip the Democratic coalition apart and thereby increase the chances of a Trump win in November — with fatal consequences for U.S. global power.

Trouble in the Taiwan Straits

While Washington is preoccupied with Gaza and Ukraine, it may also be at the threshold of a serious crisis in the Taiwan Straits. Beijing’s relentless pressure on the island of Taiwan continues unabated. Following the incremental strategy that it’s used since 2014 to secure a half-dozen military bases in the South China Sea, Beijing is moving to slowly strangle Taiwan’s sovereignty. Its breaches of the island’s airspace have increased from 400 in 2020 to 1,700 in 2023. Similarly, Chinese warships have crossed the median line in the Taiwan Straits 300 times since August 2022, effectively erasing it. As commentator Ben Lewis warned, “There soon may be no lines left for China to cross.”

After recognizing Beijing as “the sole legal Government of China” in 1979, Washington agreed to “acknowlege” that Taiwan was part of China. At the same time, however, Congress passed the Taiwan Relations Act of 1979, requiring “that the United States maintain the capacity to resist any resort to force… that would jeopardize the security… of the people on Taiwan.”

Such all-American ambiguity seemed manageable until October 2022 when Chinese President Xi Jinping told the 20th Communist Party Congress that “reunification must be realized” and refused “to renounce the use of force” against Taiwan. In a fateful counterpoint, President Biden stated, as recently as September 2022, that the US would defend Taiwan “if in fact there was an unprecedented attack.”

But Beijing could cripple Taiwan several steps short of that “unprecedented attack” by turning those air and sea transgressions into a customs quarantine that would peacefully divert all Taiwan-bound cargo to mainland China. With the island’s major ports at Taipei and Kaohsiung facing the Taiwan Straits, any American warships trying to break that embargo would face a lethal swarm of nuclear submarines, jet aircraft, and ship-killing missiles.

Given the near-certain loss of two or three aircraft carriers, the U.S. Navy would likely back off and Taiwan would be forced to negotiate the terms of its reunification with Beijing. Such a humiliating reversal would send a clear signal that, after 80 years, American dominion over the Pacific had finally ended, inflicting another major blow to U.S. global hegemony.

The Sum of Three Crises

Washington now finds itself facing three complex global crises, each demanding its undivided attention. Any one of them would challenge the skills of even the most seasoned diplomat. Their simultaneity places the U.S. in the unenviable position of potential reverses in all three at once, even as its politics at home threaten to head into an era of chaos. Playing upon American domestic divisions, the protagonists in Beijing, Moscow, and Tel Aviv are all holding a long hand (or at least a potentially longer one than Washington’s) and hoping to win by default when the U.S. tires of the game. As the incumbent, President Biden must bear the burden of any reversal, with the consequent political damage this November.

Meanwhile, waiting in the wings, Donald Trump may try to escape such foreign entanglements and their political cost by reverting to the Republican Party’s historic isolationism, even as he ensures that the former lone superpower of Planet Earth could come apart at the seams in the wake of election 2024. If so, in such a distinctly quagmire world, American global hegemony would fade with surprising speed, soon becoming little more than a distant memory.