As Romans search for alternatives to Catholicism, some have turned to Jupiter, Minerva and Juno.

Luca Fizzarotti, center, pours water on hands during a ritual with the Communitas Populi Romani, Feb. 10, 2024, near the Forum in Rome.

(RNS photo/Claire Giangravè)

February 21, 2024

By Claire Giangravé

VATICAN CITY (RNS) — Disillusioned by their experiences in Catholicism, some Romans are turning to paganism and finding a connection to their roots through worshipping the gods of antiquity, whom they see as more welcoming than the church.

“Rome is pagan,” Pope Francis told members of the Roman clergy during a closed-door meeting Jan. 14, when he urged them to consider the city a mission territory. Asked about the pope’s surprising words a few weeks later, the head of the department for catechesis of the Diocese of Rome, the Rev. Andrea Camillini, admitted: “Rome is at the same time pagan and the city of the pope: It’s a paradoxical city.”

The number of practicing Catholics in Italy has plummeted after the COVID-19 lockdowns to an all-time low. The Italian National Institute of Statistics found that only 19% of Italians were practicing Catholics in 2022, compared with 36% in the previous 10 years. The number of people who “never practice” their faith has doubled to 31% in the historically Catholic country.

While the church grapples with the causes behind the emptying pews, some who have left their Catholic faith behind are searching for other spiritual outlets. An eclectic group of Romans who gathered near the ancient Forum on a windy morning on Feb. 10 have turned to Juno, Jupiter and Apollo to find answers.

“I was a practicing Christian Catholic for many years. I was a catechist,” Luca Fizzarotti, who recently started attending the ancient Roman rituals, told Religion News Service. “Then I had a spiritual crisis when I moved in with my wife. I had a very bad experience and had to leave my church,” he said.

A computer programmer, Fizzarotti fell in love with a woman who believes in Kemetic Orthodoxy, based on the ancient Egyptian religious faith. “In the beginning I could not really understand this, then as I slowly learned about the pagan community, I found a way to live out my spirituality,” he said.

Incense burns during a ritual with the Communitas Populi Romani, Feb. 10, 2024, near the Forum in Rome. (RNS photo/Claire Giangravè)

Paganism — though sometimes used as a derogatory shorthand for anyone who does not worship the Abrahamic god of Judaism, Islam and Christianity — is an umbrella term that encompasses a number of religious traditions, many of them polytheistic. Ancient Romans worshipped a pantheon of gods, mainly Jupiter, Juno, Apollo and Minerva, through rituals and observations with activities than included animal sacrifice and temple worship.

Fizzarotti was among a dozen people who gathered for the early February ritual, organized by the Communitas Populi Romani, a community started in 2013 by a group of young enthusiasts of Roman history, culture and religion.

In the beginning, the group focused on reenactments and history, but it slowly shifted toward becoming an officially recognized religious group. There are 20 or so members, said Donatella Ertola, who joined the group in 2015 and now organizes meetings three or four times a month in the places that are closest to the original temples spread across Rome.

“We all believe in the gods, we make rituals at home, we have devotion temples at home, we have our priests and officiants,” she told RNS, adding that this is a “niche community that has been growing recently.”

Communitas is hardly the only Roman religion organization in Rome or Italy. Groups like Pietas in Rome have larger memberships and even their own temples. According to a 2017 study by the Center for Studies on New Religions in Turin, the number of neopagans in Italy has grown to more than 230,000 people, a 143% increase over 10 years. In the United States there are 1.5 million pagans, according to a 2018 Pew Research Center survey, a significant increase compared with 134,000 in 2001.

The draw of the Roman religion is clear for many modern-day Italians, who view it as a way to reconnect with their ancient roots. Fascination with ancient Rome has also become a worldwide phenomenon. A social media trend last year found a staggering and surprising number of people — especially men — think about the ancient Roman Empire at least once a day.

“I was looking for something that monotheism didn’t give me,” said Antony Meloni, an airport construction worker. “I found in polytheism a new strength,” he added.

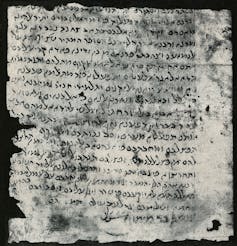

There is no religious text in the Roman religion, meaning faithful today must rely on what was written by people of the time. Communitas attempts to re-create the ancient rituals, without any human or animal sacrifice, of course, using ancient texts.

The group gathered that day to celebrate Juno Sospita, or Juno the Savior, whose temple once stood a few steps away, where the Church of St. Nickolas in Chains is located today. The original columns are still visible. She is usually shown as a warrior, lance in hand, and covered with goat skins and historically celebrated in February, considered a month of purification by the Romans, as winter turned to spring.

Communitas Populi Romani members use incense during a ritual on Feb. 10, 2024, near the Forum in Rome. (RNS photo/Claire Giangravè)

They follow the description of a ritual offered by Cato the Elder in the “De Agricultura.” It starts off with an offering to the local “genus,” or spirit, followed by ablutions with water and incense. During the central part of the ceremony, the “Favete Linguis,” faithful are asked to “hold their tongues” and quiet their minds.

Amid the chaos of Roman traffic and the occasional bark of their mascot — the dog Poldo, who has two different-colored eyes — the group shouted prayers in Latin. Two nuns, dressed in black, looked over suspiciously. Wearing a white veil, the officiant May Rega, scoffed with annoyance.

Rega was an active member of her church in Naples and sang in the choir, but she also drifted away from Catholicism due to ruptures with the church and its congregants. As an archaeologist, she loves how specific and detailed Roman religion is, forcing one to check sources, follow the ritual precisely, with no mistakes and with the appropriate citations.

She had carefully put together the flowers, scones and almond milk — because she could not find goat’s milk — for the ceremony and was annoyed when her boyfriend and concelebrant, Daniele Pieri, interrupted the ritual, forcing them to start over.

“When I met her, she said, ‘I am pagan and vegan,’ and I thought ‘Great! I am celiac!’” said Pieri, who works as a sound technician. Pieri left the Catholic Church after the parish priest insisted he could not be harmed by receiving Communion despite being celiac. He said he still has an admiration for Jesus: “If Jesus had prayed to Jupiter, he would have been even cooler.”

For Pieri, Roman religion is a question of identity. “I love this city. I was born in this city, and I want to die in this city,” he said. “When I began to study Roman history and these cults, I found my roots. This is where I come from. This is who I am.”

May Rega, center, speaks during a Communitas Populi Romani gathering on Feb. 10, 2024, near the Forum in Rome.

(RNS photo/Claire Giangravè)

Taking turns, the members of the Communitas made their personal offering to the goddess. Unlike other pagan communities in Rome, the group doesn’t have any initiation rite, and everyone is welcome to join. “The Roman religion is not about saying these are my gods, and there are no others,” Pieri explained.

Chiara Aliboni is a student of history, anthropology and religions from a “very Catholic family” in Perugia was also attending the ceremony. She said she had her conversion to Orthodox Kemetism when she learned about the ancient Egyptians. “I thought, if I am to follow any religion, it’s this one,” she said. While hesitant at first, she found in the Communitas a welcoming home for her beliefs.

Fizzarotti was also pleasantly surprised by the openness of this religion compared with his experiences in the Catholic Church. “I am drawing closer to this community. I am finding many answers that I have been searching for for years,” he said after the rite was completed, and the group reveled in wine and an improvised banquet.

“I am feeling emotional. I deeply felt today’s ritual. It was truly beautiful,” he added.

RELATED: The keeper of the Vatican’s secrets is retiring. Here’s what he wants you to know

The group members gathered their things, leaving nothing behind but the lingering scent of incense. They spoke of plans for creating a temple one day just outside Rome and of upcoming gatherings with other pagan groups. Their faith, believed to have been long lost, is still very much alive, they said.

For Camillini, as the number of Catholics dwindles in the Eternal City, he has had to face reality. “It’s time to give up the delusion of omnipotence, of evangelizing Rome, and abandon the idea of making Rome into a Christian city. It’s no longer our objective and it never was,” he said.

Taking turns, the members of the Communitas made their personal offering to the goddess. Unlike other pagan communities in Rome, the group doesn’t have any initiation rite, and everyone is welcome to join. “The Roman religion is not about saying these are my gods, and there are no others,” Pieri explained.

Chiara Aliboni is a student of history, anthropology and religions from a “very Catholic family” in Perugia was also attending the ceremony. She said she had her conversion to Orthodox Kemetism when she learned about the ancient Egyptians. “I thought, if I am to follow any religion, it’s this one,” she said. While hesitant at first, she found in the Communitas a welcoming home for her beliefs.

Fizzarotti was also pleasantly surprised by the openness of this religion compared with his experiences in the Catholic Church. “I am drawing closer to this community. I am finding many answers that I have been searching for for years,” he said after the rite was completed, and the group reveled in wine and an improvised banquet.

“I am feeling emotional. I deeply felt today’s ritual. It was truly beautiful,” he added.

RELATED: The keeper of the Vatican’s secrets is retiring. Here’s what he wants you to know

The group members gathered their things, leaving nothing behind but the lingering scent of incense. They spoke of plans for creating a temple one day just outside Rome and of upcoming gatherings with other pagan groups. Their faith, believed to have been long lost, is still very much alive, they said.

For Camillini, as the number of Catholics dwindles in the Eternal City, he has had to face reality. “It’s time to give up the delusion of omnipotence, of evangelizing Rome, and abandon the idea of making Rome into a Christian city. It’s no longer our objective and it never was,” he said.