‘Remarkable’ fossils offer clues to perplexing pterosaur question

Did these winged giants soar or flap across prehistoric skies?

By Laura Baisas

Posted on Sep 6, 2024

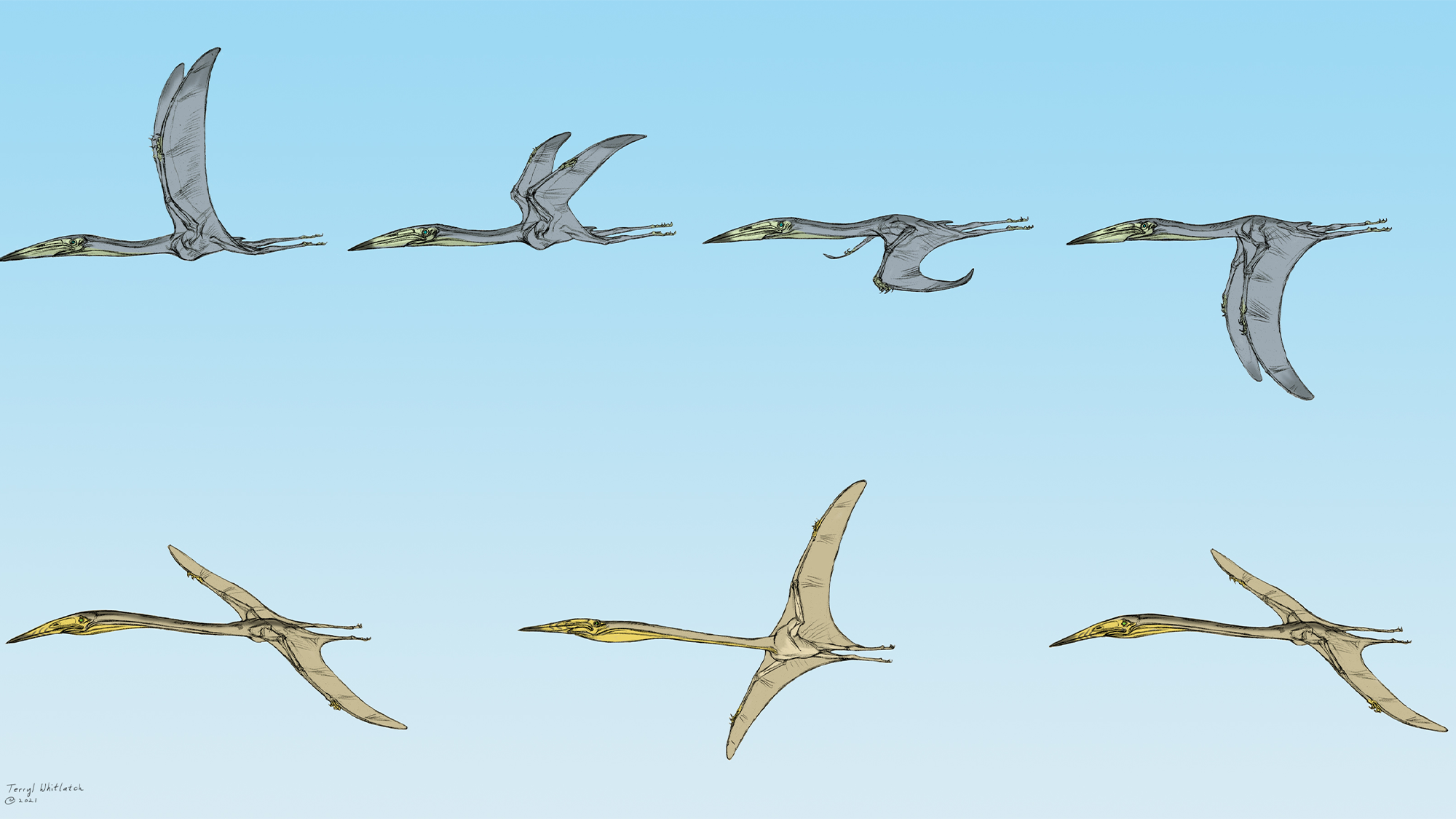

Pterosaur species Inabtanin alarabia flaps its winds, while Arambourgiania philadelphiae uses them to soar. Terryl Whitlatch

Among the many hot debates in paleontology is just how winged pterosaurs could fly. Some experts speculate that the largest among them may not have even been able to fly at all, similar to present day ostriches and similar dinosaurs.

Now, we are getting new clues into the different ways that pterosaurs got off the ground and into the sky, thanks to some well-preserved specimens. Two different large-bodied pterosaur species, including one that is new-to-science, indicate that some flew by flapping their wings, while others soared more like modern vultures. The findings are detailed in a study published September 6 in the peer-reviewed Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

[Related: We still don’t know how animals evolved to fly.]

“Pterosaurs were the earliest and largest vertebrates to evolve powered flight, but they are the only major volant group that has gone extinct,” study co-author and University of Michigan paleontologist Kierstin Rosenbach said in a statement. “Attempts to-date to understand their flight mechanics have relied on aerodynamic principles and analogy with extant birds and bats.”

Hollow bones

The fossils were first uncovered in 2007 by study co-authors Jeff Wilson Mantilla of Michigan’s Museum of Paleontology and Iyad Zalmout from the Saudi Geological Survey. The “remarkable” specimens date back roughly 72 to 66 million years ago to the Late Cretaceous period.

Over time, they were three-dimensionally preserved within two different sites of what was once the nearshore environment on the margin of Afro-Arabia. This ancient landmass that included both Africa and the Arabian Peninsula that broke apart about 30 to 35 million years ago. Using high-resolution computed tomography (CT) scans, the team analyzed the internal structure of the wing bones.

“Since pterosaur bones are hollow, they are very fragile and are more likely to be found flattened like a pancake, if they are preserved at all,” Rosenbach said. “With 3D preservation being so rare, we do not have a lot of information about what pterosaur bones look like on the inside, so I wanted to CT scan them.

According to Rosenbach, it was “entirely possible” that nothing was preserved inside the bones or that the scanners the team was using weren’t sensitive enough to differentiate fossil bone tissue from the other material that surrounded it. Fortunately, they were able to see the well-preserved internal wing structures.

[Related: Dinosaur Cove reveals a petite pterosaur species.]

Flapping vs. soaring

One of the collected specimens is of the giant pterosaur, Arambourgiania philadelphiae. The new analysis confirms its roughly 32-foot wingspan and gives the first details of its bone structure. The CT images showed that the interior of its humerus is hollow and has a series of ridges that spiral up and down the bone. This is similar to the interior wing bone of modern day vultures. Scientists believe that these spiral ridges resist the loads associated with soaring. When soaring, birds use sustained powered flight that requires launch and some maintenance flapping.

The other specimen was the newly discovered Inabtanin alarabia, with a roughly 6-foot wingspan. According to the team, Inabtanin is one of the most complete pterosaurs ever recovered from Afro-Arabia

The CT scans showed that its flight bones were built completely differently from that of Arambourgiania. The interior of Inabtanin’s flight bones were crisscrossed with struts that match those found in the wing bones of flapping birds alive today. This indicates that it was adapted to resist the bending loads in the bone associated with flapping flight. It was likely that Inabtanin flew this way, but may have also dabbled in other flight styles.

“The struts found in Inabtanin were cool to see, though not unusual,” said Rosenbach. “The ridges in Arambourgiania were completely unexpected, we weren’t sure what we were seeing at first! “Being able to see the full 3D model of Arambourgiania’s humerus lined with helical ridges was just so exciting.”

Was flapping the default?

The team called the discovery of diverse flight styles in differently-sized pterosaurs “exciting,” as it showcases how these animals might have lived. It also poses some questions, including how flight style is correlated with body size and which flight style is more common among pterosaurs.

“There is such limited information on the internal bone structure of pterosaurs across time, it is difficult to say with certainty which flight style came first,” said Rosenbach.

[Related: We were very wrong about birds.]

In flying vertebrate groups, such as birds and bats, flapping is the most common flight behavior. Birds that soar or glide, also require some wing flapping to get airborne and maintain flight

“This leads me to believe that flapping flight is the default condition, and that the behavior of soaring would perhaps evolve later if it were advantageous for the pterosaur population in a specific environment; in this case the open ocean,” said Rosenbach.

In future studies, scientists could continue to investigate the correlation between a pterosaur’s internal bone structure, their flight capacity, and behavior.