In early October, the IMO Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC 82) agreed that the concept of “polar fuels” would be further considered at a technical committee meeting in January, setting a clear pathway for future black carbon regulation.

This new course must see the IMO and its Member States develop mandatory regulations to reduce black carbon emissions - and these new rules must be prepared in a matter of months so that they can be approved at MEPC 83 in April 2025 and adopted by 2026.

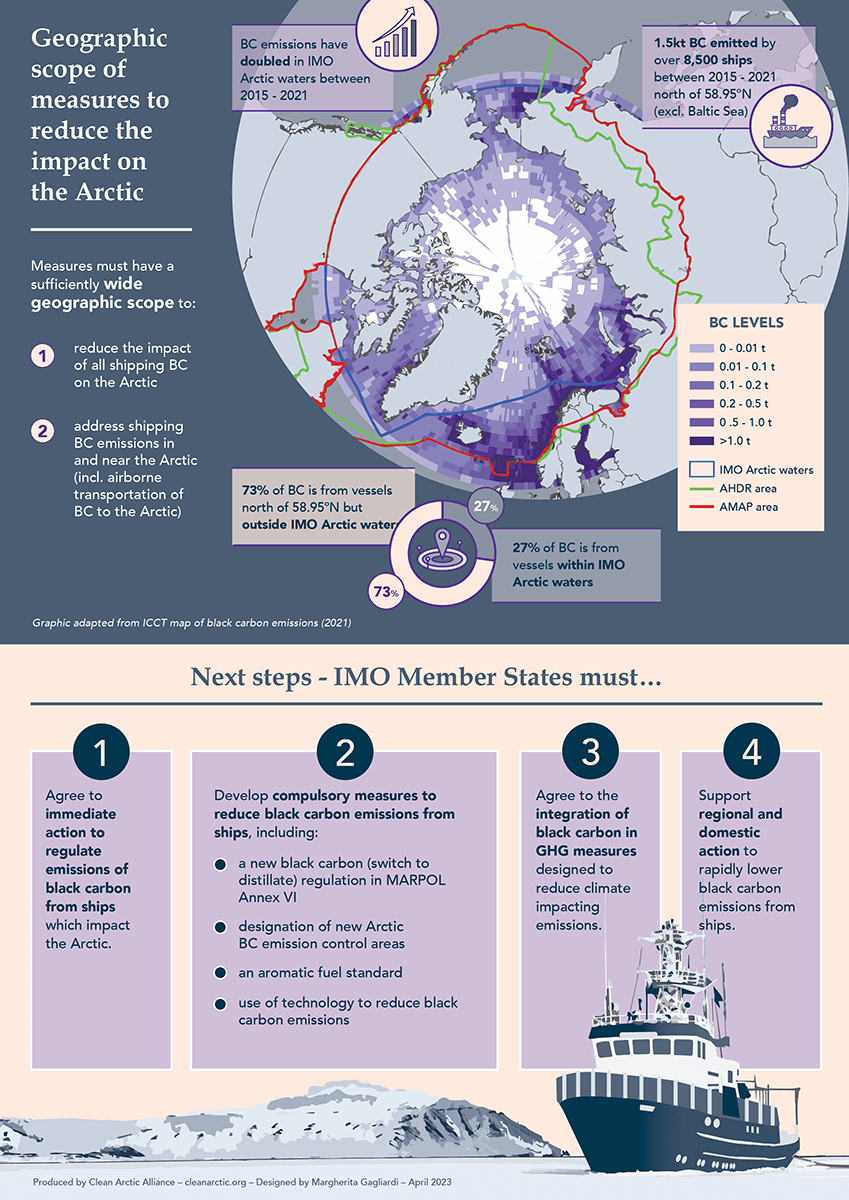

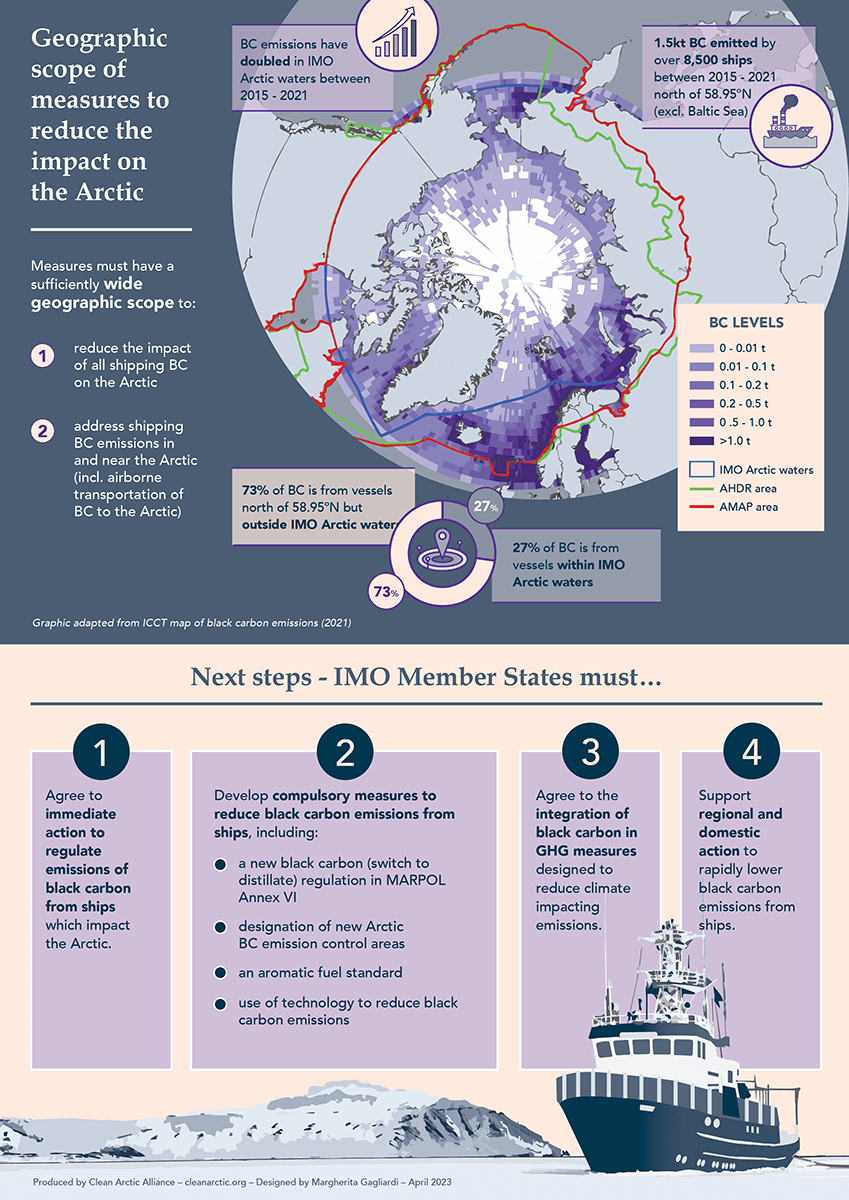

Progress is certainly to be welcomed - after all, IMO has been discussing the Arctic impact of black carbon from ships since 2011. There are many ways that ships can reduce their black carbon emissions, but without rules in place, emissions are increasing globally - and have more than doubled in the Arctic.

Black carbon is a short-lived climate pollutant, produced by the incomplete burning of fossil fuels, with an impact more than three thousand times that of CO2 over a 20-year period. It makes up around one-fifth of the climate impact of international shipping, which contributes around three percent of all human sources of climate-warming greenhouse gases. Not only does it contribute to warming while in the atmosphere, black carbon also accelerates melting when it falls onto snow and ice.

This melting exposes darker areas of land and water which then absorb further heat from the sun, while the reflective capacity of the planet’s polar ice caps is severely reduced. More heat in the polar systems results in increased melting. This is the loss of the albedo effect, and it is a serious concern: scientists recently announced that the Arctic’s reflectivity has weakened by 24% since 1980.

Declines in sea ice extent and volume are leading to a burgeoning social and environmental crisis in the Arctic, while cascading changes are impacting global climate and ocean circulation. Scientists have high confidence that processes are nearing points beyond which rapid and irreversible changes on the scale of multiple human generations are possible.

The shipping industry can reduce black carbon emissions by switching ships from using dirty residual fuels - like heavy fuel oil - to lighter distillates. This alone could reduce black carbon emissions by between 50 and 80 percent, depending on the type of engine, while installing technology such as diesel particulate filters would remove further black carbon from ships’ exhausts, much like cars today.

IMO Member States have now been tasked with providing comments and proposals on the concept of polar fuels. The Clean Arctic Alliance’s submission to MEPC 82 set out the fuel characteristics that would distinguish polar fuels from residual fuels, and thus lead to fuel-based reductions in black carbon emissions from ships. Some countries have suggested that any outcome on polar fuels could be first included in existing best practice guidance, but a number of Arctic countries at MEPC 82 supported the idea of mandatory regulation.

It would be irresponsible and reckless for the IMO to further delay the shipping sector’s response to the significant threat to the Arctic and to Arctic tipping points (changes that are virtually impossible to reverse) posed by black carbon emissions. To continue to allow unregulated emissions of a short-lived climate forcing pollutant in the Arctic is quite simply negligent, and will have unprecedented repercussions for the planet and humanity globally. There is little time left if the IMO is to have any impact on slowing down the loss of Arctic sea ice or the melting of the Greenland ice sheet.

It will be important, however, to ensure that a move from dirty heavy fuels to lighter diesel fuels does not prevent the flourishing of other cleaner new fuels or other forms of propulsion, including wind power. The black carbon regulation must be written in such a way that it requires ships operating in or near to the Arctic to move to cleaner distillate fuels, but also allows the use of “new” low- or zero-carbon, non-fossil fuels or other forms of propulsion that are now becoming commercially available.

The clock is ticking. The IMO and its Member States have just a few months to develop these mandatory regulations, which must be effective in radically reducing black carbon emissions. These new rules can and must be approved at MEPC 83 in April 2025 and adopted by 2026.

Other issues: Emission Control Areas at MEPC 82

During MEPC 82, two new emission control areas (ECA) were adopted and will come into effect from 1 March 2026, covering the Canadian Arctic waters and the Norwegian Sea. ECAs, which are sea areas with stricter rules, are designed to require ships to reduce nitrogen oxides (NOx), sulfur oxides (SOx), and particulate matter (PM) emissions. Since they also enforce the use of cleaner fuels by ships, they have a co-benefit of reducing black carbon emissions.

At MEPC 82, the Committee heard a presentation led by the government of Portugal setting out background studies for a further ECA in the North Atlantic. The boundaries of this future ECA have not yet been decided but could potentially stretch from Portuguese waters to the coast of Greenland, reducing NOx, SOx and PM, with consequent improvements in air quality and the health of coastal communities along the European western seaboard.

Creation of this ECA would ensure that black carbon emissions would be further reduced, which is good news for the Arctic. When ships sail north of 60 degrees, their impact from black carbon emissions is the greatest. However, as black carbon remains in the atmosphere for a few days or weeks, dependent on prevailing winds, it can be transported to the Arctic from further south. Any measures to reduce black carbon emissions from ships sailing north of 40 degrees North - just north of the Mediterranean Sea - will be immensely beneficial in terms of reducing the impact of shipping’s black carbon emissions on the Arctic.

While this is all very welcome news, it does not negate the need for an Arctic-wide black carbon regulation. The new ECAs and a future Atlantic ECA will improve air quality and the health of coastal populations, but until the IMO puts in place mandatory rules, shipping's black carbon emissions remain totally unregulated.

Dr Sian Prior is Lead Advisor to the Clean Arctic Alliance, and Dave Walsh is the Alliance’s Communications Advisor.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.