President Joe Biden addressed what he called "one of the darkest chapters in American history" Friday, apologizing for a brutal system that saw Native children kidnapped and abused in an effort to erase their culture.

Addressing the "trauma and shame" of "generations of children stolen," Biden slammed his fist on his podium, bellowing "I formally apologize!"

Biden called his apology one of the most consequential things he's ever been able to do

Manuel Balce Ceneta/AP/picture alliance

US President Joe Biden traveled to Arizona on Friday where he spoke with members of the Gila River Indian Community, offering a historical apology to Native peoples who suffered a century-and-a-half of unjust federal policies.

Biden, who has sought to invest in long neglected Tribal communities, as well as expanding Tribal autonomy and protections, was accompanied by US Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, the first Native American ever to serve in a Cabinet position.

Stephen Roe Lewis, governor of the Gila River Indian Community, introduced Biden, praising his "compassion, character and empathy," saying "no other president or vice president has done more for Native Americans."

Speaking to those gathered, Biden called the opportunity to offer an official apology, "one of the most consequential things I've ever been able to do."

Biden's apology was offered for decades of abuse suffered by Indian Nations at the hands of the US government and its policy of forced assimilation among Indian children.

Biden told those gathered, "The Federal Indian Board Era is one of the darkest chapters of American history. The trauma experienced in those institutions haunts our conscience to this very day."

He spoke passionately about the need "to right a wrong... to chart a new path forward," before praising "thousands of years of [Native American] culture" in government, culture and agriculture.

Addressing the "trauma and shame" of "generations of children stolen," Biden slammed his fist on his podium, bellowing "I formally apologize!"

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, the first Native American to ever serve in a Cabinet position, was instrumental in bringing the horrors of the boarding school system to lightImage: Carloyn Kaster/AP Photo/picture alliance

A perfidious scheme to 'civilize Indians'

The boarding school system, which began as part of the Indian Civilization Act of 1819, remained in place until 1970 and at one point comprised some 400 schools, many of them church-operated, across the breadth of the continent.

Over the course of 150 years, records show that more than 18,000 Native American children, some as young as four, were taken from their parents and put into abusive boarding schools aimed at eradicating Tribal cultures. In his remarks, Biden acknowledged that the true number of children taken was likely far greater.

Boys at the school, for instance, had their braids cut off and children were forbidden from speaking in their native tongue. Catholic educators condemned traditional Tribal religion as "evil," pushing forced conversions under the motto, "kill the Indian, save the man."

At least 973 children died in the schools.

First Native American Cabinet member instrumental in acknowledging historical injustices

After Haaland took over at the Department of Interior, she ordered a comprehensive review of federal boarding school policies. It was that report that motivated Biden to offer an official presidential apology.

"He made commitments to Indian country," said Haaland, "and he has followed through on every single one."

Biden, whom Haaland called "courageous," put federal protections on a number of sacred Tribal sites in the Southwest, including restoring protections for the Bears Ears National Monument in Utah, which his predecessor Donald Trump had opened to drilling and mining under Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke.

Biden on Friday, listed the many initiatives his administration had undertaken to assist Tribal communities, such as investment in infrastructure, health and education.

Political observers point out that the move by Biden during his last days in office also seeks to highlight the administration's work while attracting a very specific group of voters in a critical swing state as Vice President Kamala Harris and Trump remain in a dead heat just days before the US presidential election.

In his remarks, President Biden labeled the Federal Boarding School Era "a sin on our soul" and called for history books to be rewritten, "just because history is silent doesn't mean it didn't happen," he said, adding, "we must know who we are as a nation."

In closing, Biden spoke of hopefulness and the strengthening of ties between the federal government and Tribal Nations. While acknowledging that it was impossible to change the past, he said his apology was about "finally moving forward, into the light."

First Native American Cabinet member instrumental in acknowledging historical injustices

After Haaland took over at the Department of Interior, she ordered a comprehensive review of federal boarding school policies. It was that report that motivated Biden to offer an official presidential apology.

"He made commitments to Indian country," said Haaland, "and he has followed through on every single one."

Biden, whom Haaland called "courageous," put federal protections on a number of sacred Tribal sites in the Southwest, including restoring protections for the Bears Ears National Monument in Utah, which his predecessor Donald Trump had opened to drilling and mining under Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke.

Biden on Friday, listed the many initiatives his administration had undertaken to assist Tribal communities, such as investment in infrastructure, health and education.

Political observers point out that the move by Biden during his last days in office also seeks to highlight the administration's work while attracting a very specific group of voters in a critical swing state as Vice President Kamala Harris and Trump remain in a dead heat just days before the US presidential election.

In his remarks, President Biden labeled the Federal Boarding School Era "a sin on our soul" and called for history books to be rewritten, "just because history is silent doesn't mean it didn't happen," he said, adding, "we must know who we are as a nation."

In closing, Biden spoke of hopefulness and the strengthening of ties between the federal government and Tribal Nations. While acknowledging that it was impossible to change the past, he said his apology was about "finally moving forward, into the light."

js/lo (AFP, Reuters)

President Biden to issue boarding school apology – at last

The president will be at Gila River Indian Community to acknowledge the trauma wreaked by U.S. forced assimilation policies *UPDATED

MARY ANNETTE PEMBER

UPDATED:

OCT 24, 2024

President Joe Biden, shown here at a news conference on July 11, 2024, in Washington, will issue an apology on Friday, Oct. 25, 2024, on behalf of the United States for its destructive boarding school policies. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin, File)

More than 150 years after the first Native children were forced to attend Indian boarding schools that robbed them of their families, culture and language, President Joe Biden will issue a long-awaited apology for the dark history that has left generational damage among Indigenous peoples.

Biden is set to present the apology and a plan for helping tribal communities heal from the enduring traumas on Friday, Oct. 25, at the Gila River Indian Community in Arizona, marking his first visit to tribal lands as president

It’s an apology that Native people have been seeking for decades.

“This apology is an acknowledgement that the President of the United States sees and hears them,” said U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, Laguna Pueblo, whose family members attended Indian boarding schools.

“This is an acknowledgement of a horrific history,” Haaland told ICT in an interview. “This happened in our country.”

Boarding school survivor Jim LaBelle, Inupiaq, right, speaks to Interior Secretary Deb Haaland and Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Bryan Newland during the Interior Department's "Road to Healing" meeting on Oct. 22, 2023, in Anchorage, Alaska. The tours are being held around the U.S. to hear from survivors of Indian boarding schools. (AP Photo/Mark Thiessen)

For Deb Parker, chief executive of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, known as NABS, it was an emotional moment to learn an apology would finally be made.

“It’s time,” Parker said, her voice taut with emotion as she waited to board Air Force One Thursday on her way to Arizona with Biden, Haaland. Five tribal leaders were also on the plane, including Gila River Indian Community Gov. Stephen Roe Lewis, Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin Chairwoman Gena Kakkak, Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation Chairman Rodney Butler and Bay Mills Indian Community Chairwoman Whitney Gravelle.

“I think he has it in his heart to understand the pain and trauma that we and our loved ones have suffered,” said Parker, of the Tulalip Tribes. “It takes a strong president to deliver this apology.”

Deborah Parker, Tulalip, is chief executive of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, known as NABS. She poses for a photo following the Interior Department's press conference on its federal boarding school investigation in Washington, D.C. on Wednesday, May 11, 2022. (Photo by Jourdan Bennett-Begaye/ICT)

The apology comes just three months after the U.S. Department of the Interior released a final report in July of its investigation into the U.S. boarding school system after gathering evidence and witness testimony during a year-long “Road to Healing Tour.”

The first item on the Federal Indian Boarding School Investigative Report’s list of recommendations was for the United States to apologize for and acknowledge that generations of Native children were stolen from their families, and often severely beaten and abused in government and private boarding schools. Many of them died at the schools and were never sent home.

The recommendations also call for a Truth and Healing Commission to investigate further, a memorial to acknowledge those who attended, and for the U.S. to invest in tribal communities to help individual and community healing, revitalization of Native languages and improvements to Indian education. Details of Biden’s proposals had not been released by Thursday afternoon.

Haaland described the president’s apology for the U.S.’s role in operating Indian boarding schools as an example of his ongoing commitment to Indian Country.

“It’s very meaningful to me and I think it will be meaningful to many people,” Haaland told ICT.

Navajo President Buu Nygren praised Biden's decision. His grandmother was taken to the Sherman Institute Indian boarding school in Riverside, California, about 700 miles from the Navajo Nation, he said in a statement.

"This dark chapter caused untold suffering, trauma, and loss, and its impact still reverberates in our communities today, "Nygren said. "By recognizing this tragic legacy, President Biden honors the resilience of the survivors and their families, many of whom carry the weight of these experiences ...

"Ahe'hee', thank you, President Biden, for your commitment to reconciliation and justice," he said.

Why has it taken so long?

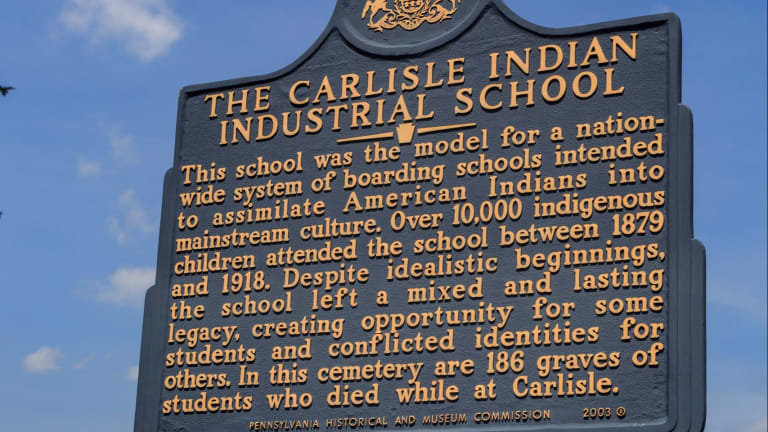

The United States lags years behind Canada and even the Catholic Church in offering an apology for residential boarding schools, which were largely patterned after the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania.

Thousands of Native children attended those schools in the U.S. and many died at the schools without ever returning to their families.

Canada’s then-Prime Minister Stephen Harper apologized in 2008 for the government’s role in operating Indian residential schools in 2008, and Pope Francis apologized in 2022 in Canada for the role played by members of the Catholic Church in running residential schools. The U.S. Catholic Bishops apologized this year for the church’s role in boarding schools.

“In order to apologize, you have to recognize that something wrong happened,” Parker said. “I don’t think the United States was ready to acknowledge what they did, not only to Native children but also the parents, grandparents and the entire community.”

“This was a crime; now it’s time to examine that crime.”

Pope Francis prepares to deliver his apology to Indigenous people in Canada on July 25, 2022, in Maskwacis, Alberta, Canada, with chiefs of the four nations on whose land he stood. (Photo by Miles Morrisseau/ICT)

Haaland, the first Native member of a presidential cabinet, spent more than a year on the cross-country Road to Healing Tour, gathering testimony from boarding school survivors and family members. Bryan Newland, assistant secretary of the Bureau of Indian Affairs who is of the Bay Mills Community, also attended, and authored the final report and recommendations.

Haaland described listening to hundreds of stories from boarding school survivors and descendants during the tour. Haaland’s grandparents and great-grandparents were taken away from their families to attend boarding schools.

“I’ve lived this all of my life,” she said. “The federal government spent exorbitant amounts of taxpayer funding to essentially eradicate the Native culture, languages and traditions of these children.”

Headstones at the cemetery on the grounds of the former Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania mark the graves of children who died at the school. (Photo by the Associated Press)

While in Congress as a U.S. representative from New Mexico, Haaland worked with U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts to introduce a bill in 2020 to create a Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policy in the United States. The bill was later redrafted and re-introduced in Congress, and is now awaiting a vote in Congress.

“We went to Capitol Hill and testified in support of that bill,” Haaland said. “There’s not a lot of time left, but I hope Congress makes the right decision.”

Few people in the United States outside of Indian Country were even aware of Indian boarding school history, Haaland said.

The president will be at Gila River Indian Community to acknowledge the trauma wreaked by U.S. forced assimilation policies *UPDATED

MARY ANNETTE PEMBER

UPDATED:

OCT 24, 2024

President Joe Biden, shown here at a news conference on July 11, 2024, in Washington, will issue an apology on Friday, Oct. 25, 2024, on behalf of the United States for its destructive boarding school policies. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin, File)

More than 150 years after the first Native children were forced to attend Indian boarding schools that robbed them of their families, culture and language, President Joe Biden will issue a long-awaited apology for the dark history that has left generational damage among Indigenous peoples.

Biden is set to present the apology and a plan for helping tribal communities heal from the enduring traumas on Friday, Oct. 25, at the Gila River Indian Community in Arizona, marking his first visit to tribal lands as president

It’s an apology that Native people have been seeking for decades.

“This apology is an acknowledgement that the President of the United States sees and hears them,” said U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, Laguna Pueblo, whose family members attended Indian boarding schools.

“This is an acknowledgement of a horrific history,” Haaland told ICT in an interview. “This happened in our country.”

Boarding school survivor Jim LaBelle, Inupiaq, right, speaks to Interior Secretary Deb Haaland and Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Bryan Newland during the Interior Department's "Road to Healing" meeting on Oct. 22, 2023, in Anchorage, Alaska. The tours are being held around the U.S. to hear from survivors of Indian boarding schools. (AP Photo/Mark Thiessen)

For Deb Parker, chief executive of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, known as NABS, it was an emotional moment to learn an apology would finally be made.

“It’s time,” Parker said, her voice taut with emotion as she waited to board Air Force One Thursday on her way to Arizona with Biden, Haaland. Five tribal leaders were also on the plane, including Gila River Indian Community Gov. Stephen Roe Lewis, Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin Chairwoman Gena Kakkak, Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation Chairman Rodney Butler and Bay Mills Indian Community Chairwoman Whitney Gravelle.

“I think he has it in his heart to understand the pain and trauma that we and our loved ones have suffered,” said Parker, of the Tulalip Tribes. “It takes a strong president to deliver this apology.”

Deborah Parker, Tulalip, is chief executive of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, known as NABS. She poses for a photo following the Interior Department's press conference on its federal boarding school investigation in Washington, D.C. on Wednesday, May 11, 2022. (Photo by Jourdan Bennett-Begaye/ICT)

The apology comes just three months after the U.S. Department of the Interior released a final report in July of its investigation into the U.S. boarding school system after gathering evidence and witness testimony during a year-long “Road to Healing Tour.”

The first item on the Federal Indian Boarding School Investigative Report’s list of recommendations was for the United States to apologize for and acknowledge that generations of Native children were stolen from their families, and often severely beaten and abused in government and private boarding schools. Many of them died at the schools and were never sent home.

The recommendations also call for a Truth and Healing Commission to investigate further, a memorial to acknowledge those who attended, and for the U.S. to invest in tribal communities to help individual and community healing, revitalization of Native languages and improvements to Indian education. Details of Biden’s proposals had not been released by Thursday afternoon.

Haaland described the president’s apology for the U.S.’s role in operating Indian boarding schools as an example of his ongoing commitment to Indian Country.

“It’s very meaningful to me and I think it will be meaningful to many people,” Haaland told ICT.

Navajo President Buu Nygren praised Biden's decision. His grandmother was taken to the Sherman Institute Indian boarding school in Riverside, California, about 700 miles from the Navajo Nation, he said in a statement.

"This dark chapter caused untold suffering, trauma, and loss, and its impact still reverberates in our communities today, "Nygren said. "By recognizing this tragic legacy, President Biden honors the resilience of the survivors and their families, many of whom carry the weight of these experiences ...

"Ahe'hee', thank you, President Biden, for your commitment to reconciliation and justice," he said.

Why has it taken so long?

The United States lags years behind Canada and even the Catholic Church in offering an apology for residential boarding schools, which were largely patterned after the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania.

Thousands of Native children attended those schools in the U.S. and many died at the schools without ever returning to their families.

Canada’s then-Prime Minister Stephen Harper apologized in 2008 for the government’s role in operating Indian residential schools in 2008, and Pope Francis apologized in 2022 in Canada for the role played by members of the Catholic Church in running residential schools. The U.S. Catholic Bishops apologized this year for the church’s role in boarding schools.

“In order to apologize, you have to recognize that something wrong happened,” Parker said. “I don’t think the United States was ready to acknowledge what they did, not only to Native children but also the parents, grandparents and the entire community.”

“This was a crime; now it’s time to examine that crime.”

Pope Francis prepares to deliver his apology to Indigenous people in Canada on July 25, 2022, in Maskwacis, Alberta, Canada, with chiefs of the four nations on whose land he stood. (Photo by Miles Morrisseau/ICT)

Haaland, the first Native member of a presidential cabinet, spent more than a year on the cross-country Road to Healing Tour, gathering testimony from boarding school survivors and family members. Bryan Newland, assistant secretary of the Bureau of Indian Affairs who is of the Bay Mills Community, also attended, and authored the final report and recommendations.

Haaland described listening to hundreds of stories from boarding school survivors and descendants during the tour. Haaland’s grandparents and great-grandparents were taken away from their families to attend boarding schools.

“I’ve lived this all of my life,” she said. “The federal government spent exorbitant amounts of taxpayer funding to essentially eradicate the Native culture, languages and traditions of these children.”

Headstones at the cemetery on the grounds of the former Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania mark the graves of children who died at the school. (Photo by the Associated Press)

While in Congress as a U.S. representative from New Mexico, Haaland worked with U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts to introduce a bill in 2020 to create a Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policy in the United States. The bill was later redrafted and re-introduced in Congress, and is now awaiting a vote in Congress.

“We went to Capitol Hill and testified in support of that bill,” Haaland said. “There’s not a lot of time left, but I hope Congress makes the right decision.”

Few people in the United States outside of Indian Country were even aware of Indian boarding school history, Haaland said.

The Wrap: Biden's historic apology calls boarding school history ‘a sin on our soul’

Indigenous headlines for Friday, Oct. 25, 2024

ICT

A complicated history of presidential visits

The American story is complicated and contradictory. And yet the words Friday from President Joe Biden will be clear and simple. It will be an apology for the federal government’s boarding school policy. That clarity – and reversal of what was done in the past – will take place at the Gila River Indian Community in Arizona during an official presidential visit.

More than a century ago President Chester Arthur first visited a tribal nation (on horseback) as an official visit. That president was promoting a policy of assimilation – and the boarding schools were the instrument of cultural erasure. In a message to Congress he asked for a “liberal appropriation for the support of Indian schools, because of my confident belief that such a course is consistent with the wisest economy. … They are doubtless much more potent for good than the day schools upon the reservation, as the pupils are altogether separated from the surroundings of savage life, and brought into constant contact with civilization.”

Indigenous headlines for Friday, Oct. 25, 2024

ICT

Greetings, relatives.

A lot of news out there. Thanks for stopping by ICT’s digital platform.

Each day we do our best to gather the latest news for you. Remember to scroll to the bottom to see what’s popping out to us on social media and what we’re reading.

Okay, here's what you need to know today:

Historic Apology: Boarding school history ‘a sin on our soul’

GILA RIVER INDIAN COMMUNITY — President Joe Biden delivered an historic apology Friday on behalf of the United States for the nation’s dark past with Indian boarding schools, which sought to wipe out Native people, culture and language.

Calling the federal boarding school policies “a sin on our soul,” Biden drew cheers, tears and at least one protester among the hundreds of the mostly Indigenous crowd gathered for the long-awaited announcement.

A lot of news out there. Thanks for stopping by ICT’s digital platform.

Each day we do our best to gather the latest news for you. Remember to scroll to the bottom to see what’s popping out to us on social media and what we’re reading.

Okay, here's what you need to know today:

Historic Apology: Boarding school history ‘a sin on our soul’

GILA RIVER INDIAN COMMUNITY — President Joe Biden delivered an historic apology Friday on behalf of the United States for the nation’s dark past with Indian boarding schools, which sought to wipe out Native people, culture and language.

Calling the federal boarding school policies “a sin on our soul,” Biden drew cheers, tears and at least one protester among the hundreds of the mostly Indigenous crowd gathered for the long-awaited announcement.

A complicated history of presidential visits

The American story is complicated and contradictory. And yet the words Friday from President Joe Biden will be clear and simple. It will be an apology for the federal government’s boarding school policy. That clarity – and reversal of what was done in the past – will take place at the Gila River Indian Community in Arizona during an official presidential visit.

More than a century ago President Chester Arthur first visited a tribal nation (on horseback) as an official visit. That president was promoting a policy of assimilation – and the boarding schools were the instrument of cultural erasure. In a message to Congress he asked for a “liberal appropriation for the support of Indian schools, because of my confident belief that such a course is consistent with the wisest economy. … They are doubtless much more potent for good than the day schools upon the reservation, as the pupils are altogether separated from the surroundings of savage life, and brought into constant contact with civilization.”

— Mark Trahant, ICT

A complicated history of presidential visits

Policy swings from assimilation to sovereignty

President Barack Obama holds a Native American baby as he joins the members of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Nation, in Cannon Ball, N.D., Friday, June 13, 2014, during a Cannon Ball flag day celebration, at the Cannon Ball powwow grounds. It’s the president’s first trip to Indian Country as president and only the third such visit by a sitting president in almost 80 years.

Policy swings from assimilation to sovereignty

President Barack Obama holds a Native American baby as he joins the members of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Nation, in Cannon Ball, N.D., Friday, June 13, 2014, during a Cannon Ball flag day celebration, at the Cannon Ball powwow grounds. It’s the president’s first trip to Indian Country as president and only the third such visit by a sitting president in almost 80 years.

(AP Photo/Manuel Balce Ceneta)

ICT

BY MARK TRAHANT

Mark Trahant, Shoshone-Bannock, is based in Phoenix. On Threads, Instagram: @TrahantReports. Trahant is based in Phoenix.

Indian Country Today is a nonprofit news organization. Will you support our work? All of our content is free. There are no subscriptions or costs. And we have hired more Native journalists in the past year than any news organization ─ and with your help we will continue to grow and create career paths for our people. Support Indian Country Today for as little as $10.

The American story is complicated and contradictory. And yet the words Friday from President Joe Biden will be clear and simple. It will be an apology for the federal government’s boarding school policy. That clarity – and reversal of what was done in the past – will take place at the Gila River Indian Community in Arizona during an official presidential visit.

More than a century ago President Chester Arthur first visited a tribal nation (on horseback) as an official visit. That president was promoting a policy of assimilation – and the boarding schools were the instrument of cultural erasure. In a message to Congress he asked for a “liberal appropriation for the support of Indian schools, because of my confident belief that such a course is consistent with the wisest economy. … They are doubtless much more potent for good than the day schools upon the reservation, as the pupils are altogether separated from the surroundings of savage life, and brought into constant contact with civilization.”

President Chester A. Arthur visiting Fort Washakie, Wyo. Terr., 1883 (War Department photo)

He told Congress that it was time to end the policy of dealing with tribes as nations (“and a savage life”) and instead focus on “efforts to bring them under the influences of civilization.”

The president’s trip to the Wind River Reservation was supposed to make it so. A bill in the Senate would have divided the land individually. But neither the Shoshones nor the Arapaho agreed with that notion, so Arthur had to reverse the policy and leave the reservation intact (a policy that led to two major intra-tribal disputes). One of the Arapaho leaders, Sharp Nose, had sent his son to a boarding school to “learn how to do as the white men do … We give our children to the Government to do as they think best in teaching them the right way, hoping that the officers will, after a while, permit us to go and see them.”

Sharp nose never saw his son again. He died in 1883.

President Biden to issue boarding school apology – at last

Read More

Arthur’s trip to Wind River was not intentional. He was traveling to Yellowstone to fish. That was a common route to Indian Country. In 1927, President Calvin Coolidge was visiting South Dakota and opted to visit Pine Ridge.

(This happens a lot: The White House in 1927 called it the first visit by a sitting president to a tribal nation.)

The White House history reports that President Coolidge greeted some 500 Lakota who sang and danced. Tribal leaders pressed the president about their ownership of the Black Hill.

Instead Coolidge, like Arthur, championed assimilation and boarding schools.

And the Lakota have never accepted payment for the Black Hills.

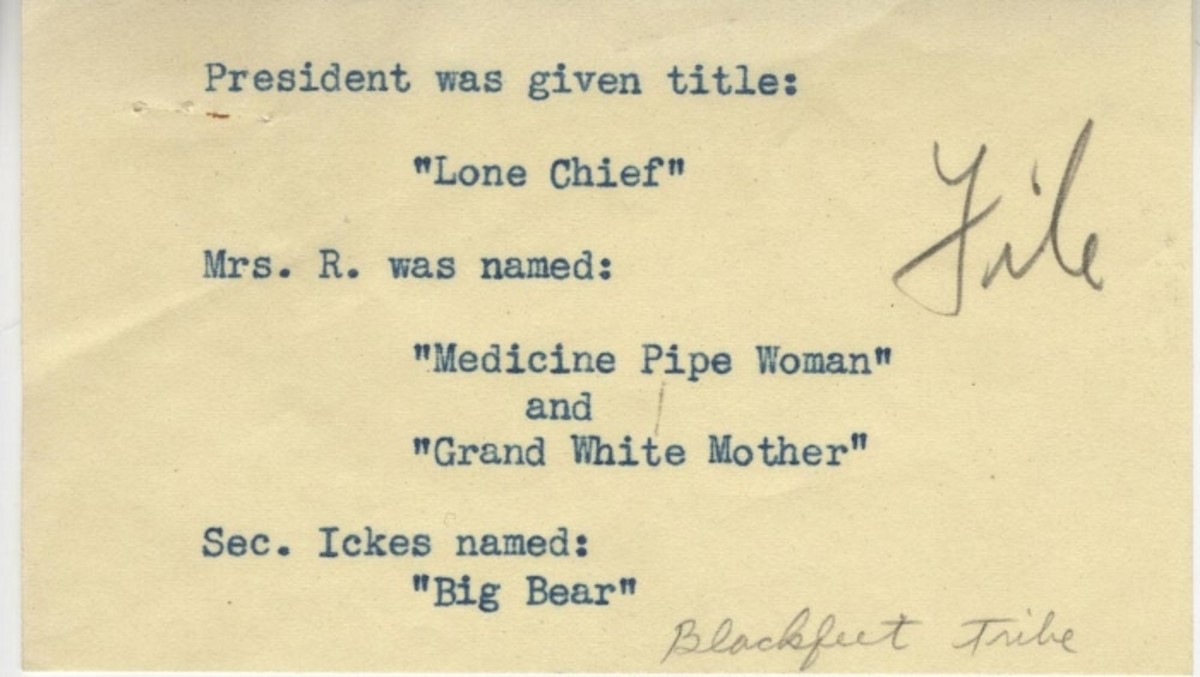

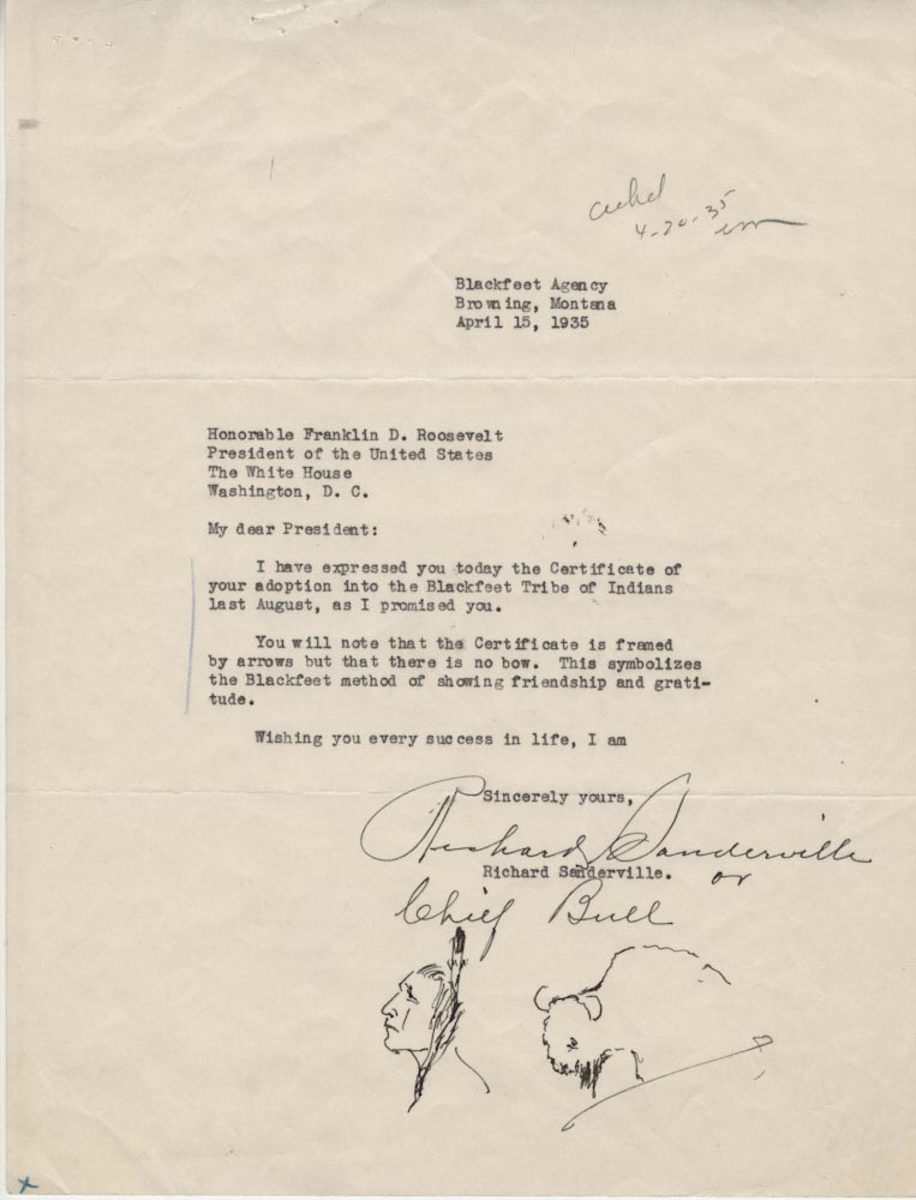

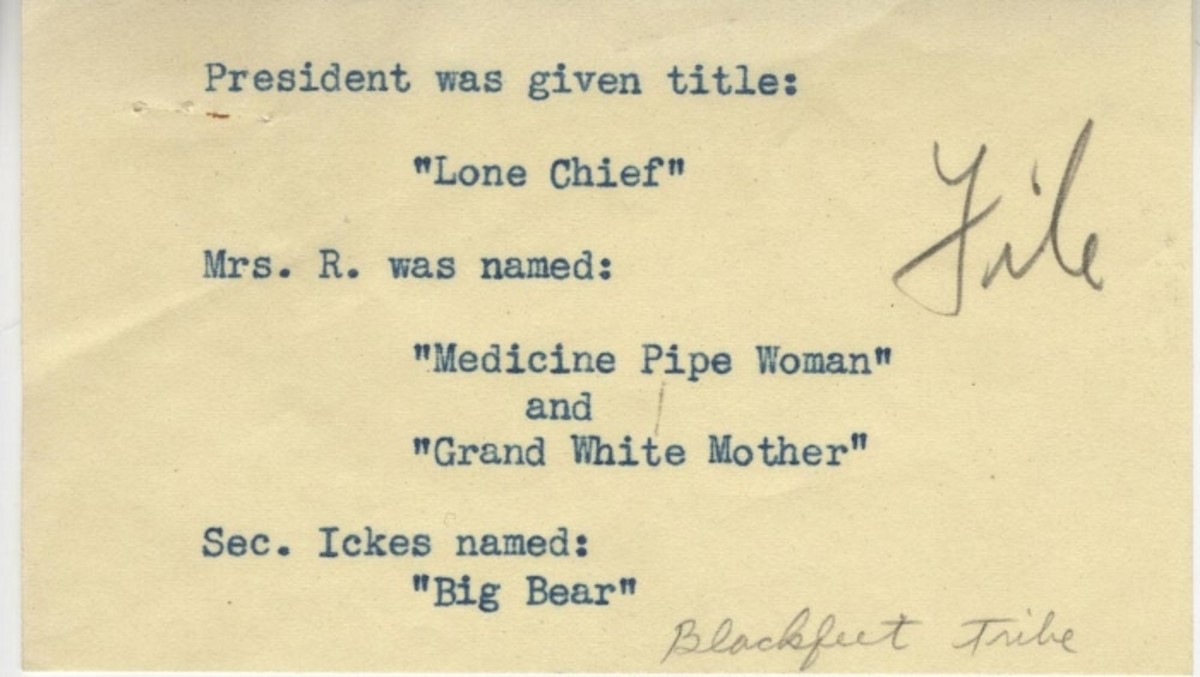

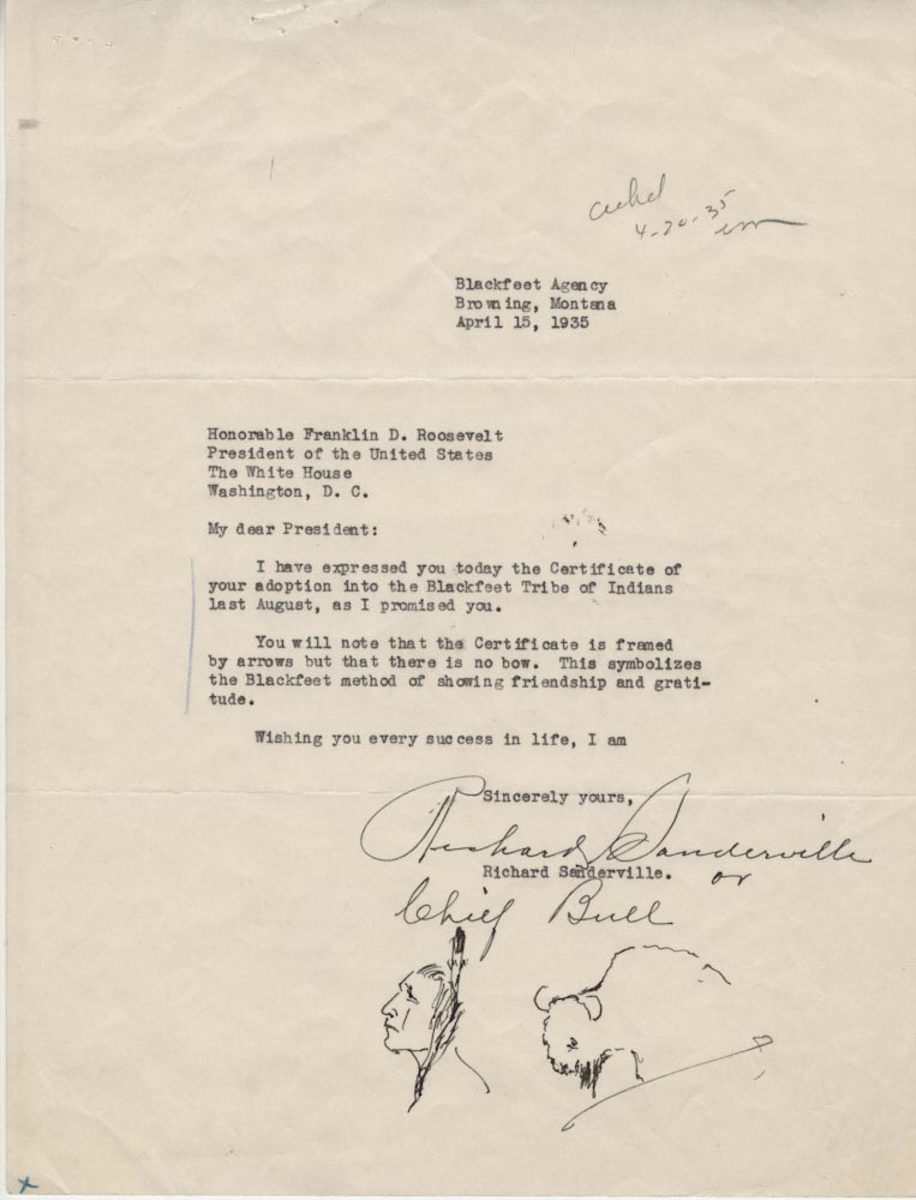

Other presidential visits are less about policy. President Franklin D. Roosevelt visited tribal nations at least four times, Quinault, in Washington state, Blackfeet in Montana, Fort Peck in Montana, and Cherokee, North Carolina. At Blackfeet, the president was honored and given the name “Lone Chief.”

In 1985, President Ronald Reagan met with Navajo President Peterson Zah and Hopi Tribal Chairman Ivan Sidney in an attempt to resolve the Navajo-Hopi Land Dispute – the mess created by Chester Arthur’s executive order.

Richard Nixon did not visit a tribal nation but his staff really wanted him to do so twice. (The memos from WH aide Brad Patterson to his colleagues were passionate.) He was invited to celebrate with Taos Pueblo over the return of Blue Lake. However, instead of going, the president sent the teenage daughter of his vice president, Spiro Agnew. Nixon’s second non-visit would have been to Tsaile to launch what was then Navajo Community College (now Diné College).

The language of sovereignty – not assimilation – is now the story framework. This started with President Bill Clinton’s visit to Pine Ridge, South Dakota, and Shiprock, New Mexico, in 2000. Clinton talked about technology and learning – and the power of Diné College.

President Barack Obama, like Clinton, talked about technology and the talent of Native Youth, leading to several initiatives including Generation Indigenous.

President Barack Obama participates in a performance by native Alaskan dancers at Dillingham Middle School, Wednesday, Sept. 2, 2015, in Dillingham, Alaska. Obama is on a historic three-day trip to Alaska aimed at showing solidarity with a state often overlooked by Washington, while using its glorious but changing landscape as an urgent call to action on climate change. (AP Photo/Andrew Harnik)

And during Obama’s visit to Alaska he was even more direct about the importance of protecting the Native way of life. “My administration also is taking new action to make sure that Alaska Natives have direct input into the management of Chinook salmon stocks (plus) everything from voting rights to land trusts.”

Presidential visits to tribal nations are punctuated by the complicated and contradictory policies of the United States. A century ago it was all about assimilation, erasure, and yes, boarding schools. Today the language is about culture, sovereignty and protecting the value of Native youth.

President Joe Biden’s visit is from this chapter of sovereignty. He’s also the first U.S. president to make a direct apology for the disastrous boarding school policy.

Mark Trahant, Shoshone-Bannock, is editor-at-large for Indian Country Today.

ICT is owned by IndiJ Public Media, a nonprofit news organization. Will you support our work? All of our content is free. There are no subscriptions or costs. And we have hired more Native journalists in the past year than any news organization ─ and with your help we will continue to grow and create career paths for our people. Support ICT for as little as $10. Sign up for ICT’s free newsletter.

More than a century ago President Chester Arthur first visited a tribal nation (on horseback) as an official visit. That president was promoting a policy of assimilation – and the boarding schools were the instrument of cultural erasure. In a message to Congress he asked for a “liberal appropriation for the support of Indian schools, because of my confident belief that such a course is consistent with the wisest economy. … They are doubtless much more potent for good than the day schools upon the reservation, as the pupils are altogether separated from the surroundings of savage life, and brought into constant contact with civilization.”

President Chester A. Arthur visiting Fort Washakie, Wyo. Terr., 1883 (War Department photo)

He told Congress that it was time to end the policy of dealing with tribes as nations (“and a savage life”) and instead focus on “efforts to bring them under the influences of civilization.”

The president’s trip to the Wind River Reservation was supposed to make it so. A bill in the Senate would have divided the land individually. But neither the Shoshones nor the Arapaho agreed with that notion, so Arthur had to reverse the policy and leave the reservation intact (a policy that led to two major intra-tribal disputes). One of the Arapaho leaders, Sharp Nose, had sent his son to a boarding school to “learn how to do as the white men do … We give our children to the Government to do as they think best in teaching them the right way, hoping that the officers will, after a while, permit us to go and see them.”

Sharp nose never saw his son again. He died in 1883.

President Biden to issue boarding school apology – at last

Read More

Arthur’s trip to Wind River was not intentional. He was traveling to Yellowstone to fish. That was a common route to Indian Country. In 1927, President Calvin Coolidge was visiting South Dakota and opted to visit Pine Ridge.

(This happens a lot: The White House in 1927 called it the first visit by a sitting president to a tribal nation.)

The White House history reports that President Coolidge greeted some 500 Lakota who sang and danced. Tribal leaders pressed the president about their ownership of the Black Hill.

Instead Coolidge, like Arthur, championed assimilation and boarding schools.

And the Lakota have never accepted payment for the Black Hills.

Other presidential visits are less about policy. President Franklin D. Roosevelt visited tribal nations at least four times, Quinault, in Washington state, Blackfeet in Montana, Fort Peck in Montana, and Cherokee, North Carolina. At Blackfeet, the president was honored and given the name “Lone Chief.”

In 1985, President Ronald Reagan met with Navajo President Peterson Zah and Hopi Tribal Chairman Ivan Sidney in an attempt to resolve the Navajo-Hopi Land Dispute – the mess created by Chester Arthur’s executive order.

Richard Nixon did not visit a tribal nation but his staff really wanted him to do so twice. (The memos from WH aide Brad Patterson to his colleagues were passionate.) He was invited to celebrate with Taos Pueblo over the return of Blue Lake. However, instead of going, the president sent the teenage daughter of his vice president, Spiro Agnew. Nixon’s second non-visit would have been to Tsaile to launch what was then Navajo Community College (now Diné College).

The language of sovereignty – not assimilation – is now the story framework. This started with President Bill Clinton’s visit to Pine Ridge, South Dakota, and Shiprock, New Mexico, in 2000. Clinton talked about technology and learning – and the power of Diné College.

President Barack Obama, like Clinton, talked about technology and the talent of Native Youth, leading to several initiatives including Generation Indigenous.

President Barack Obama participates in a performance by native Alaskan dancers at Dillingham Middle School, Wednesday, Sept. 2, 2015, in Dillingham, Alaska. Obama is on a historic three-day trip to Alaska aimed at showing solidarity with a state often overlooked by Washington, while using its glorious but changing landscape as an urgent call to action on climate change. (AP Photo/Andrew Harnik)

And during Obama’s visit to Alaska he was even more direct about the importance of protecting the Native way of life. “My administration also is taking new action to make sure that Alaska Natives have direct input into the management of Chinook salmon stocks (plus) everything from voting rights to land trusts.”

Presidential visits to tribal nations are punctuated by the complicated and contradictory policies of the United States. A century ago it was all about assimilation, erasure, and yes, boarding schools. Today the language is about culture, sovereignty and protecting the value of Native youth.

President Joe Biden’s visit is from this chapter of sovereignty. He’s also the first U.S. president to make a direct apology for the disastrous boarding school policy.

Mark Trahant, Shoshone-Bannock, is editor-at-large for Indian Country Today.

ICT is owned by IndiJ Public Media, a nonprofit news organization. Will you support our work? All of our content is free. There are no subscriptions or costs. And we have hired more Native journalists in the past year than any news organization ─ and with your help we will continue to grow and create career paths for our people. Support ICT for as little as $10. Sign up for ICT’s free newsletter.

BY MARK TRAHANT

Mark Trahant, Shoshone-Bannock, is based in Phoenix. On Threads, Instagram: @TrahantReports. Trahant is based in Phoenix.

Indian Country Today is a nonprofit news organization. Will you support our work? All of our content is free. There are no subscriptions or costs. And we have hired more Native journalists in the past year than any news organization ─ and with your help we will continue to grow and create career paths for our people. Support Indian Country Today for as little as $10.

Apologize! Report calls for US government to own up to abusive boarding school history

“The Road to Healing does not end with this report – it is just beginning,”

MARY ANNETTE PEMBER AND STEWART HUNTINGTON

JUL 30, 2024

ICT

WARNING: This story contains disturbing details about residential and boarding schools. If you are feeling triggered, here is a resource list for trauma responses from the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition in the U.S. In Canada, the National Indian Residential School Crisis Hotline can be reached at 1-866-925-4419.

The U.S. Department of the Interior released its final investigative report Tuesday on the ugly history of federal Indian boarding schools, calling for a formal apology from the U.S. government and ongoing support to help Native people recover from the generational trauma that endures.

The second — and concluding — report from the department’s Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative also calls for return of lands that once housed the boarding schools, and construction of a national memorial to honor the children who were separated from their families and forced to attend schools that sought to wipe out their culture, identity and language.

The overarching theme of the boarding school initiative report and recommendations is that of healing for Indian Country, with a list of specific ways the federal government can tangibly assist tribal nations and peoples. It also reported that hundreds of additional children are now known to have died at the boarding schools and that additional burial sites had been discovered.

“The federal government – facilitated by the department I lead – took deliberate and strategic actions through federal Indian boarding school policies to isolate children from their families, deny them their identities, and steal from them the languages, cultures and connections that are foundational to Native people,” Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, Laguna Pueblo, said in a statement released with the report.

“These policies caused enduring trauma for Indigenous communities that the Biden-Harris administration is working tirelessly to repair,” said Haaland, who became the first Native person to be included in a presidential cabinet when she was tapped by President Joe Biden to lead the department.

“The Road to Healing does not end with this report – it is just beginning,” she said.

During a press conference Tuesday afternoon outlining the report’s findings, Haaland appeared to choke up when discussing the impact the schools have had on Native families, including her own.

“History has shaped our nation and … for too long it's been swept under the rug,” she said. “All while communities grapple with the undeniable fallout of intergenerational trauma. I'm so proud of the strength of our team, our accomplishments here today, and where this initiative will lead us. We are here because our ancestors persevered. It is our duty to share their stories.”

The report and its recommendations were authored by Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Bryan Newland, a citizen of the Bay Mills Indian Community.

“For the first time in the history of the United States, the federal government is accounting for its role in operating historical Indian boarding schools that forcibly confined and attempted to assimilate Indigenous children,” Newland said in a statement.

“This report further proves what Indigenous peoples across the country have known for generations – that federal policies were set out to break us, obtain our territories, and destroy our cultures and our lifeways,” Newland said. “It is undeniable that those policies failed, and now, we must bring every resource to bear to strengthen what they could not destroy. It is critical that this work endures, and that federal, state and tribal governments build on the important work accomplished as part of the Initiative.”

Ruth Anna Buffalo, president of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, said the report is a good step but that more research and effort are needed.

The coalition has led efforts to bring the facts of the boarding school era out of history's shadows, focusing its efforts on the people most impacted by the schools — especially the Native ancestors who died at the schools but remain uncounted.

"The report is important for the families of those directly affected, for those left with no answers," said Buffalo, a citizen of the Mandan Hidatsa Arikara Nation. "It's a heavy topic that deserves to be handled with love and care. ... Our ancestors were very spiritual people and I find it hard to comprehend how they were treated in such a way."

The wounds of the era hit home for Buffalo and her family.

"Unfortunately, it's a common thread for the First Peoples of these lands," to have personal, lived experience with boarding school-era trauma, she said. "There is much more work that needs to be done."

Hundreds more deaths

The Department of the Interior’s final report of the Federal Boarding School Initiative largely makes good on promises from its initial report issued in May 2022, which called for continuing the investigation into the scope of the federal boarding school system.

Haaland’s initiative and the launch of the investigation in 2021 represented the first official U.S. effort to acknowledge the existence of the boarding school era and its negative impact on Native peoples.

The initial report for the first time included historical records of boarding school names and locations, and the first official list of burial sites of children who died at the schools.

The latest report, which officials said included a review of more than 100 million pages of documents, expands on those findings to report that student deaths at boarding schools are nearly double what had previously been reported, increasing from an estimated 500 to 973.

The estimated number of identified boarding schools also increased, from 407 to 417, and the number of “other” institutions such as orphanages and asylums with similar missions of assimilation increased from 1,000 to 1,025.

Researchers verified the identity of 18,624 students who attended boarding schools from 1819 to 1969, and identified 74 marked or unmarked burial sites at schools versus 53 sites shared in the first report.

The report also estimates that the U.S. government budgeted more than $23 billion, converted to 2023 U.S. dollars, on the federal boarding school system.

Notably, the latest report contains additional findings and recommendations that are more specific than those found in the past document, and in all cases, authors stated that the actual numbers in all categories will likely increase as research continues.

The latest report comes as Congress is making progress on legislation in the House and Senate that would create a Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policies with authority to investigate not just federal schools but also private and church-run schools.

Deb Parker, chief executive of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, noted that the ntroduction to the report is a letter from Newland that cites an incident in which the U.S. military took 104 Hopi children from their families and sent them to boarding school. The U.S. Cavalry then returned to arrest 19 Hopi leaders as prisoners of war after they refused to send any more children.

“This is just one incident of hundreds or thousands,” said Parker, Tulalip Tribes. “[But] when one amplifies this across the country, it tells a horrific story. It’s devastating not only to children but also to communities and their families.”

Parker said NABS has been interviewing boarding school survivors across the country as part of a project with the Department of the Interior, funded by the Mellon Foundation and Bureau of Indian Affairs.

“The stories are mostly devastating in nature,” she said. “It’s so concerning that for so many, this is the first opportunity they have had to tell their stories and receive some sort of acknowledgement of the pain they’ve endured.”

She continued, “We are reeling from these stories and trying to understand our next steps. I believe this second volume of the DOI report is incredibly important in helping guide us in taking these next steps. It’s important to listen to survivors and hear their recommendations directly…. I think we’re headed in the right direction.”

A series of recommendations

The latest report outlines a series of eight recommendations that appear to be guided, at least in part, by steps that Canada took in response to that country’s Indian residential school history, which closely mirrors the U.S.

Indigenous leaders show up in force at Democratic National Convention

Unlike the U.S., however, which has only recently recognized such a history existed, Canada began its work with an apology in 2006 before moving on to reparations and other substantive actions.

The U.S. commission would be patterned after the Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was created as part of the 2008 Indian Settlement Act. Canada eventually paid to residential school survivors more than $3 billion in reparations, which are notably absent from the U.S. initiative’s recommendations.

When asked about financial reparations, Newland said, “During the Road to Healing tour when we were listening to survivors about their experiences and their families, they’re weren’t a lot of specific calls for compensation or damages to individuals. What we did hear a lot was about the need for real resources for community based healing, language revitalization and things we’ve highlighted in the report. There’s a lot of work to yet to be done. It’s important to turn these broad recommendations into concrete steps; that’s got to be the endeavor of our entire government.”

Haaland added, “There are trust and treaty obligations that our government made with tribes, and we need to uphold those."

The Canadian government also collected survivor stories, provided traditional and mainstream mental health supports, issued a government apology, collected and made boarding school records publicly available and helped locate unmarked graves of children who died and were buried at the schools.

The U.S. Indian boarding school system served as a model for Canada and operated far more schools, with 417 schools compared to 139 in Canada.

Haaland and Newland traveled the country on an historic “Road to Healing” tour, with 12 stops that provided Indigenous survivors the opportunity to share for the first time with the federal government their experiences in federal Indian boarding schools. Transcripts of the tour, which finished in late 2023, are available on the Federal Boarding School Initiative website.

The Interior Department also launched an oral history project documenting and making public experiences of generations of boarding school survivors. Funded by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Mellon Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition is interviewing survivors for what will be a collection of first-person narratives that will be shared with the public.

“This report further proves what Indigenous peoples across the country have known for generations – that federal policies were set out to break us, obtain our territories, and destroy our cultures and our lifeways,” said Newland. “It is undeniable that those policies failed, and now, we must bring every resource to bear to strengthen what they could not destroy. It is critical that this work endures, and that federal, state and tribal governments build on the important work accomplished as part of the Initiative.”

Ongoing efforts

The report also states that the Department of the Interior is working with tribes to repatriate or protect human remains and funerary objects from Indian boarding schools sites located on U.S. government lands, and will do so under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.

The efforts will include remains at the former Carlisle Indian Industrial School, where nearly 180 students who died at the school are buried. The site is controlled by the U.S. Army.

The Land Back recommendation will also be ongoing, with calls for return to tribes of the Indian lands that the government provided to religious organizations and states for the purpose of building schools. In many cases, the lands were to have reverted back to tribal ownership if organizations stopped operating schools.

Churches and other organizations, however, continue to hold some of this land today long after boarding schools closed. In an independent investigation, ICT found that Catholic entities may continue to hold more than 10,000 acres of these lands.

The report also identifies 127 treaties made between the federal government and tribes in which boarding schools figure highly, and calls for the U.S. to make good on its promises in treaties and other legislation to provide quality education for Native Americans as well as essential Indigenous language preservation curriculum.

‘Anger and hurt’

Reactions from tribal leaders were mixed, though many praised the report.

Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. noted that Oklahoma had more federal Indian boarding schools than any other state, with 87, and that 18 of the children known to have died at boarding school identified as Cherokee.

“The operation of federal Indian boarding schools in this country marked a troubling chapter in our history,” Hoskin said Tuesday in a statement. “We have witnessed, in recent years, a renewed effort to have transparent and difficult discussions about this country’s history of operating Native American boarding schools, and much of this effort is a result of Secretary Haaland’s ongoing investigation into the government’s past oversight of these federally operated facilities.

He continued, “This report is long overdue, but it is also appreciated. We hope that the next steps beyond this federal investigation help account for the injustices that have occurred and that we can begin to heal some of the generational traumas Native people still struggle with as a result of past anti-Indian policies and practices.”

Peter Lengkeek, the chairman of the Great Crow Creek Sioux Tribe in South Dakota, welcomed the report but said the wounds from the boarding school era remain deep.

“I believe it is a step in the right direction,” he said. “But coming into the tribal office I stopped different [individuals] and asked their opinions. ‘If someone was to come to you and say they want to make it right with tribes, what would that look like?’ The common (answer) was, ‘It doesn't matter what they do, I still have this anger and hurt in my heart.’”

The pain from the era is still alive on Lengkeek’s reservation, which is not far from the St. Joseph Indian School in Chamberlain, South Dakota. The school is still in operation but no longer operates under the policies of the boarding school era.

“My brothers… went to Vietnam after and fought in war. To this day what bothers them is St. Joseph Indian School, not the war. The school. I can’t imagine what they went through for that to be worse than war,” Lengkeek said.

Ben Barnes, chief of the Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma, praised Haaland and Newland for pulling the report together.

"I think this is the beginning of a longer road of healing and reconciliation," Barnes said. "Speaking as a Native person, I know how my own individual life was affected by my family members’ experience at boarding schools. I can see how those boarding schools have caused ongoing trauma in Native communities. I find that learning more about the boarding school past gives me a lot of forgiveness that I didn’t know I needed to have for those in our communities who struggle. It gives me space to find some forgiveness and understanding on how they got to the place they’re at."

Amy Sazue, executive director of Remembering the Children, a memorial project for children who died at the now-shuttered Rapid City Indian Boarding School, thanked Haaland for the investigation.

“I'm just really filled with gratitude for her and remember when she said that [the Department of the Interior] was a tool used against our people for a long time,” said Sazue, Sicangu Lakota. “So having her in that position has really been a good example of what happens when we have representation in those places.”

In Minneapolis, LeMoine LaPointe, a Sicangu Lakota elder who works as an Indigenous cultural consultant fostering positive conversations in Native communities, acknowledged the difficulties inherent in the report — and its release.

“This country has never addressed the horrendousness of the boarding school era. It’s hard to swallow the truth,” he said. But he said Natives can lead the way forward to “a more positive and beneficial place.”

“Despite the genocide and despite the historical trauma, we, Native people, are still the repository of healing,” he said. “Within our Indigenous knowledge we have systems of healing that we can develop for ourselves and also help the broader community.”

Muscogee (Creek) Nation spokesperson Jason Salsman said the report stirs conflicting emotions.

“The atrocities and horrors of the government-led attempt to erase Native people and culture through these institutions is still a very real impact today,” Salsman said. “ But there is also a feeling of triumph and recognition. We have overcome, and are still here. Our culture, our language and our ways live on and remain strong."

Report highlights

The Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative’s second and final investigative report released Tuesday, July 30, 2024, by the U.S. Department of the Interior includes eight recommendations from Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Bryan Newland, who authored the report. Here are recommendations:

*Apology: The U.S. government should acknowledge its role in a national policy of forced assimilation of Native children and issue a formal apology to individuals, families and tribes that were harmed by U.S. policy.

*Investments: The U.S. should invest in tribal communities in five key areas: individual and community healing; family preservation and reunification, including supporting tribal jurisdiction over Indian child welfare cases; violence prevention on tribal lands; improving Indian education; and working to revitalize First American languages.

*A national memorial: The U.S. government should establish a national memorial to acknowledge and commemorate the experiences of Native people within the federal Indian boarding school system.

*Repatriations: The government should identify children interred at school burial sites and help repatriate their remains

*Return school lands: The government should work to return the federal Indian boarding school sites to tribal ownership.

*Tell the story: The government should work with institutions to educate the public about federal Indian boarding schools and their impact on communities.

*Further research: The government should study how policies of child removal, confinement and forced assimilation have impacted generations of families, particularly the present-day health and economic impacts

*Advance international relations: The government should work with other countries such as Canada, Australia and New Zealand with their own similar but unique histories of boarding schools and assimilationist policies, to determine best practices for healing and redress.

ICT journalists Shirley Sneve, Amelia Schafer and Felix Clary contributed to this report.

*Updated: This story has been updated with additional reactions to the report.

BY MARY ANNETTE PEMBER

Mary Annette Pember, a citizen of the Red Cliff Ojibwe tribe, is a national correspondent for ICT.

Follow @mapember

BY STEWART HUNTINGTON

Stewart Huntington is an ICT producer/reporter based in central Colorado.

“The Road to Healing does not end with this report – it is just beginning,”

The final investigative report on federal Indian boarding schools sets out recommendations for helping Native communities heal from the abusive policies *Updated

James Nells, Navajo, a U.S. combat veteran, carries an eagle staff as part of the color guard presentation beginning the "Road to Healing" hearing at Riverside Indian boarding school in Anadarko, Oklahoma, on Saturday, July 9, 2022. Survivors of boarding schools told U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, Laguna Pueblo, of the abuses they sustained at the schools. (Photo by Mary Annette Pember/ICT)

James Nells, Navajo, a U.S. combat veteran, carries an eagle staff as part of the color guard presentation beginning the "Road to Healing" hearing at Riverside Indian boarding school in Anadarko, Oklahoma, on Saturday, July 9, 2022. Survivors of boarding schools told U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, Laguna Pueblo, of the abuses they sustained at the schools. (Photo by Mary Annette Pember/ICT)

MARY ANNETTE PEMBER AND STEWART HUNTINGTON

JUL 30, 2024

ICT

WARNING: This story contains disturbing details about residential and boarding schools. If you are feeling triggered, here is a resource list for trauma responses from the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition in the U.S. In Canada, the National Indian Residential School Crisis Hotline can be reached at 1-866-925-4419.

The U.S. Department of the Interior released its final investigative report Tuesday on the ugly history of federal Indian boarding schools, calling for a formal apology from the U.S. government and ongoing support to help Native people recover from the generational trauma that endures.

The second — and concluding — report from the department’s Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative also calls for return of lands that once housed the boarding schools, and construction of a national memorial to honor the children who were separated from their families and forced to attend schools that sought to wipe out their culture, identity and language.

The overarching theme of the boarding school initiative report and recommendations is that of healing for Indian Country, with a list of specific ways the federal government can tangibly assist tribal nations and peoples. It also reported that hundreds of additional children are now known to have died at the boarding schools and that additional burial sites had been discovered.

“The federal government – facilitated by the department I lead – took deliberate and strategic actions through federal Indian boarding school policies to isolate children from their families, deny them their identities, and steal from them the languages, cultures and connections that are foundational to Native people,” Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, Laguna Pueblo, said in a statement released with the report.

“These policies caused enduring trauma for Indigenous communities that the Biden-Harris administration is working tirelessly to repair,” said Haaland, who became the first Native person to be included in a presidential cabinet when she was tapped by President Joe Biden to lead the department.

“The Road to Healing does not end with this report – it is just beginning,” she said.

During a press conference Tuesday afternoon outlining the report’s findings, Haaland appeared to choke up when discussing the impact the schools have had on Native families, including her own.

“History has shaped our nation and … for too long it's been swept under the rug,” she said. “All while communities grapple with the undeniable fallout of intergenerational trauma. I'm so proud of the strength of our team, our accomplishments here today, and where this initiative will lead us. We are here because our ancestors persevered. It is our duty to share their stories.”

The report and its recommendations were authored by Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Bryan Newland, a citizen of the Bay Mills Indian Community.

“For the first time in the history of the United States, the federal government is accounting for its role in operating historical Indian boarding schools that forcibly confined and attempted to assimilate Indigenous children,” Newland said in a statement.

“This report further proves what Indigenous peoples across the country have known for generations – that federal policies were set out to break us, obtain our territories, and destroy our cultures and our lifeways,” Newland said. “It is undeniable that those policies failed, and now, we must bring every resource to bear to strengthen what they could not destroy. It is critical that this work endures, and that federal, state and tribal governments build on the important work accomplished as part of the Initiative.”

Ruth Anna Buffalo, president of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, said the report is a good step but that more research and effort are needed.

The coalition has led efforts to bring the facts of the boarding school era out of history's shadows, focusing its efforts on the people most impacted by the schools — especially the Native ancestors who died at the schools but remain uncounted.

"The report is important for the families of those directly affected, for those left with no answers," said Buffalo, a citizen of the Mandan Hidatsa Arikara Nation. "It's a heavy topic that deserves to be handled with love and care. ... Our ancestors were very spiritual people and I find it hard to comprehend how they were treated in such a way."

The wounds of the era hit home for Buffalo and her family.

"Unfortunately, it's a common thread for the First Peoples of these lands," to have personal, lived experience with boarding school-era trauma, she said. "There is much more work that needs to be done."

Hundreds more deaths

The Department of the Interior’s final report of the Federal Boarding School Initiative largely makes good on promises from its initial report issued in May 2022, which called for continuing the investigation into the scope of the federal boarding school system.

Haaland’s initiative and the launch of the investigation in 2021 represented the first official U.S. effort to acknowledge the existence of the boarding school era and its negative impact on Native peoples.

The initial report for the first time included historical records of boarding school names and locations, and the first official list of burial sites of children who died at the schools.

The latest report, which officials said included a review of more than 100 million pages of documents, expands on those findings to report that student deaths at boarding schools are nearly double what had previously been reported, increasing from an estimated 500 to 973.

The estimated number of identified boarding schools also increased, from 407 to 417, and the number of “other” institutions such as orphanages and asylums with similar missions of assimilation increased from 1,000 to 1,025.

Researchers verified the identity of 18,624 students who attended boarding schools from 1819 to 1969, and identified 74 marked or unmarked burial sites at schools versus 53 sites shared in the first report.

The report also estimates that the U.S. government budgeted more than $23 billion, converted to 2023 U.S. dollars, on the federal boarding school system.

Notably, the latest report contains additional findings and recommendations that are more specific than those found in the past document, and in all cases, authors stated that the actual numbers in all categories will likely increase as research continues.

The latest report comes as Congress is making progress on legislation in the House and Senate that would create a Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policies with authority to investigate not just federal schools but also private and church-run schools.

Deb Parker, chief executive of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, noted that the ntroduction to the report is a letter from Newland that cites an incident in which the U.S. military took 104 Hopi children from their families and sent them to boarding school. The U.S. Cavalry then returned to arrest 19 Hopi leaders as prisoners of war after they refused to send any more children.

“This is just one incident of hundreds or thousands,” said Parker, Tulalip Tribes. “[But] when one amplifies this across the country, it tells a horrific story. It’s devastating not only to children but also to communities and their families.”

Parker said NABS has been interviewing boarding school survivors across the country as part of a project with the Department of the Interior, funded by the Mellon Foundation and Bureau of Indian Affairs.

“The stories are mostly devastating in nature,” she said. “It’s so concerning that for so many, this is the first opportunity they have had to tell their stories and receive some sort of acknowledgement of the pain they’ve endured.”

She continued, “We are reeling from these stories and trying to understand our next steps. I believe this second volume of the DOI report is incredibly important in helping guide us in taking these next steps. It’s important to listen to survivors and hear their recommendations directly…. I think we’re headed in the right direction.”

A series of recommendations

The latest report outlines a series of eight recommendations that appear to be guided, at least in part, by steps that Canada took in response to that country’s Indian residential school history, which closely mirrors the U.S.

Indigenous leaders show up in force at Democratic National Convention

Unlike the U.S., however, which has only recently recognized such a history existed, Canada began its work with an apology in 2006 before moving on to reparations and other substantive actions.

The U.S. commission would be patterned after the Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was created as part of the 2008 Indian Settlement Act. Canada eventually paid to residential school survivors more than $3 billion in reparations, which are notably absent from the U.S. initiative’s recommendations.

When asked about financial reparations, Newland said, “During the Road to Healing tour when we were listening to survivors about their experiences and their families, they’re weren’t a lot of specific calls for compensation or damages to individuals. What we did hear a lot was about the need for real resources for community based healing, language revitalization and things we’ve highlighted in the report. There’s a lot of work to yet to be done. It’s important to turn these broad recommendations into concrete steps; that’s got to be the endeavor of our entire government.”

Haaland added, “There are trust and treaty obligations that our government made with tribes, and we need to uphold those."

The Canadian government also collected survivor stories, provided traditional and mainstream mental health supports, issued a government apology, collected and made boarding school records publicly available and helped locate unmarked graves of children who died and were buried at the schools.

The U.S. Indian boarding school system served as a model for Canada and operated far more schools, with 417 schools compared to 139 in Canada.

Haaland and Newland traveled the country on an historic “Road to Healing” tour, with 12 stops that provided Indigenous survivors the opportunity to share for the first time with the federal government their experiences in federal Indian boarding schools. Transcripts of the tour, which finished in late 2023, are available on the Federal Boarding School Initiative website.

The Interior Department also launched an oral history project documenting and making public experiences of generations of boarding school survivors. Funded by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Mellon Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition is interviewing survivors for what will be a collection of first-person narratives that will be shared with the public.

“This report further proves what Indigenous peoples across the country have known for generations – that federal policies were set out to break us, obtain our territories, and destroy our cultures and our lifeways,” said Newland. “It is undeniable that those policies failed, and now, we must bring every resource to bear to strengthen what they could not destroy. It is critical that this work endures, and that federal, state and tribal governments build on the important work accomplished as part of the Initiative.”

Ongoing efforts

The report also states that the Department of the Interior is working with tribes to repatriate or protect human remains and funerary objects from Indian boarding schools sites located on U.S. government lands, and will do so under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.

The efforts will include remains at the former Carlisle Indian Industrial School, where nearly 180 students who died at the school are buried. The site is controlled by the U.S. Army.

The Land Back recommendation will also be ongoing, with calls for return to tribes of the Indian lands that the government provided to religious organizations and states for the purpose of building schools. In many cases, the lands were to have reverted back to tribal ownership if organizations stopped operating schools.

Churches and other organizations, however, continue to hold some of this land today long after boarding schools closed. In an independent investigation, ICT found that Catholic entities may continue to hold more than 10,000 acres of these lands.

The report also identifies 127 treaties made between the federal government and tribes in which boarding schools figure highly, and calls for the U.S. to make good on its promises in treaties and other legislation to provide quality education for Native Americans as well as essential Indigenous language preservation curriculum.

‘Anger and hurt’

Reactions from tribal leaders were mixed, though many praised the report.

Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. noted that Oklahoma had more federal Indian boarding schools than any other state, with 87, and that 18 of the children known to have died at boarding school identified as Cherokee.

“The operation of federal Indian boarding schools in this country marked a troubling chapter in our history,” Hoskin said Tuesday in a statement. “We have witnessed, in recent years, a renewed effort to have transparent and difficult discussions about this country’s history of operating Native American boarding schools, and much of this effort is a result of Secretary Haaland’s ongoing investigation into the government’s past oversight of these federally operated facilities.

He continued, “This report is long overdue, but it is also appreciated. We hope that the next steps beyond this federal investigation help account for the injustices that have occurred and that we can begin to heal some of the generational traumas Native people still struggle with as a result of past anti-Indian policies and practices.”

Peter Lengkeek, the chairman of the Great Crow Creek Sioux Tribe in South Dakota, welcomed the report but said the wounds from the boarding school era remain deep.

“I believe it is a step in the right direction,” he said. “But coming into the tribal office I stopped different [individuals] and asked their opinions. ‘If someone was to come to you and say they want to make it right with tribes, what would that look like?’ The common (answer) was, ‘It doesn't matter what they do, I still have this anger and hurt in my heart.’”

The pain from the era is still alive on Lengkeek’s reservation, which is not far from the St. Joseph Indian School in Chamberlain, South Dakota. The school is still in operation but no longer operates under the policies of the boarding school era.

“My brothers… went to Vietnam after and fought in war. To this day what bothers them is St. Joseph Indian School, not the war. The school. I can’t imagine what they went through for that to be worse than war,” Lengkeek said.

Ben Barnes, chief of the Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma, praised Haaland and Newland for pulling the report together.

"I think this is the beginning of a longer road of healing and reconciliation," Barnes said. "Speaking as a Native person, I know how my own individual life was affected by my family members’ experience at boarding schools. I can see how those boarding schools have caused ongoing trauma in Native communities. I find that learning more about the boarding school past gives me a lot of forgiveness that I didn’t know I needed to have for those in our communities who struggle. It gives me space to find some forgiveness and understanding on how they got to the place they’re at."

Amy Sazue, executive director of Remembering the Children, a memorial project for children who died at the now-shuttered Rapid City Indian Boarding School, thanked Haaland for the investigation.

“I'm just really filled with gratitude for her and remember when she said that [the Department of the Interior] was a tool used against our people for a long time,” said Sazue, Sicangu Lakota. “So having her in that position has really been a good example of what happens when we have representation in those places.”

In Minneapolis, LeMoine LaPointe, a Sicangu Lakota elder who works as an Indigenous cultural consultant fostering positive conversations in Native communities, acknowledged the difficulties inherent in the report — and its release.

“This country has never addressed the horrendousness of the boarding school era. It’s hard to swallow the truth,” he said. But he said Natives can lead the way forward to “a more positive and beneficial place.”

“Despite the genocide and despite the historical trauma, we, Native people, are still the repository of healing,” he said. “Within our Indigenous knowledge we have systems of healing that we can develop for ourselves and also help the broader community.”

Muscogee (Creek) Nation spokesperson Jason Salsman said the report stirs conflicting emotions.

“The atrocities and horrors of the government-led attempt to erase Native people and culture through these institutions is still a very real impact today,” Salsman said. “ But there is also a feeling of triumph and recognition. We have overcome, and are still here. Our culture, our language and our ways live on and remain strong."

Report highlights

The Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative’s second and final investigative report released Tuesday, July 30, 2024, by the U.S. Department of the Interior includes eight recommendations from Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Bryan Newland, who authored the report. Here are recommendations:

*Apology: The U.S. government should acknowledge its role in a national policy of forced assimilation of Native children and issue a formal apology to individuals, families and tribes that were harmed by U.S. policy.