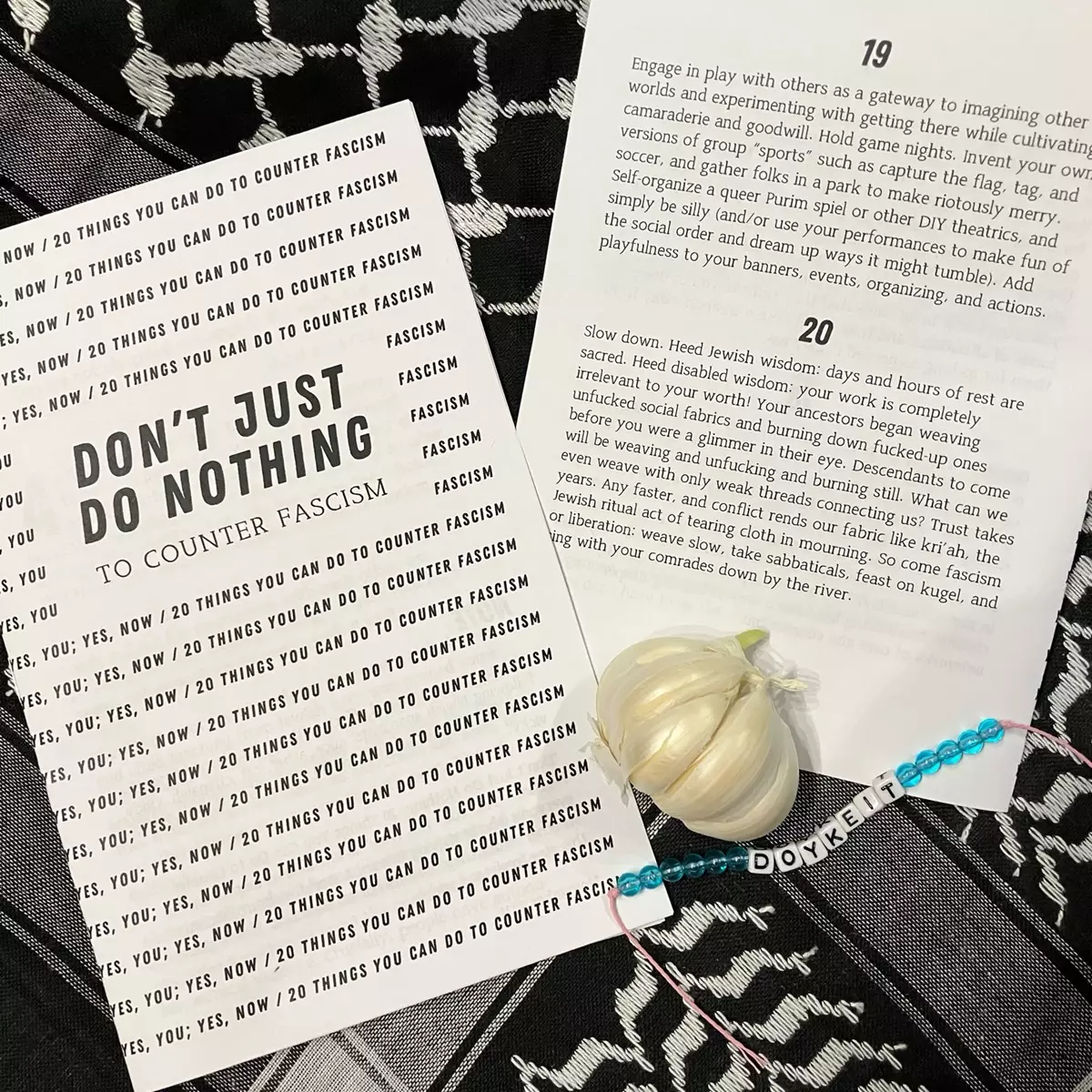

Don’t Just Do Nothing

From It's Going Down

Original title: "Don’t Just Do Nothing: 20 Things You Can Do to Counter Fascism"

Jewish anarchists weigh-in on how people can organize and act in the changing terrain. For a zine PDF, go here.

You are not obligated to complete the work, but neither are you free to desist from it. —Pirkei Avot (2:21)

As Christofascism takes the reins of US power, thereby impacting the whole of this continent and the globe, it should be abundantly clear at this point that appealing to the state—any state—is a losing strategy. The world had already lost when the “choice” this November was between two versions of fascism.

We offer up this sampler of ideas, encouraging you to think and act for yourselves, with each other, as precisely the only winning strategy. If each idea here seems not enough on its own—well, it isn’t.

The Pirkei Avot quote, perhaps the most widely known and cited teaching from Jewish text, was penned some two thousand years ago. So many forms of despotism—empires, monarchies, and states—have risen and fallen in that time. We are not alone, as anarchists and Jews, in our ethical imperative to wrestle with every type of authority.

Ancestors throughout human history—people of all colors, genders, and cultures of this earth—have struggled together to resist the imposition of coercive, hierarchical violence. Crucially, people have autonomously organized, defended, and practiced myriad forms of mutual aid, collective care, and self-governance for millennia—what is often called “prefigurative politics.” They haven’t put off the worlds they want to see but instead have directly acted as if they were already free.

As diasporic rebels, our Jewishness teaches us to rely on solidarity beyond all borders. Our teachings compel us to lean on the community of others to live lives worth living, whether we are mourning or celebrating, or grappling time and again with what liberation should and could look like. When we start Shabbat each week—twenty-five hours of practicing “the world to come”—and end it with Havdalah—when we ease ourselves back into this brutal “world as it is”—we do so with braided offerings (bread and a candle, respectively). Such braids, in these times, underscore the imperative for interwovenness, for interrelationality, between each and every one of us, from all walks of life, who want to destroy fascism and bring about liberatory social transformations.

May all freedom-seeking peoples journey side by side toward those aspirations by better loving and caring for each other.

Here are twenty things you can do to counter fascism—yes, you! yes, now! Dream up and put into motion many, many more things too. This is only a beginning.

1. Do doikayt (hereness) within your one-on-one relationships. What would it look like to check in with each of your beloveds based on your current conditions and communicate with love to each other what you envision for the world you want to build? Identify the soil amendments necessary in thought, word, and deed for those seeds to flourish.

2. Make people soup and do not stop inviting them over for soup! Be a reason for living.

3. Build a support network. Join with like-minded people and organize for quality over quantity; a few devoted comrades can go further than a large and dispassionate group. Make art about it. Your support network, the love of your friends and family, can always be broader; build it bigger, with care and intentionality. Make more art about it. Try out new actions: talk to people and ask how they’re feeling, distribute literature, organize a study group, or put up stickers or disperse seed bombs together. With every loving bond we forge, and all the new art we make, we divorce ourselves a little more from the demons that haunt us — hopelessness, irony, and complacency — and find sparks of possibility. Try, fail, and try again and again.

4. Buy, accumulate, or otherwise procure Plan B, and save it for yourself and others in case it’s needed later. Set up a Plan B distro in your community. Do the same with other, potentially soon-hard-to-access supplies related to bodily autonomy.

5. Write letters to people in prison and detention, send them books, and/or do jail support and solidarity for those facing state repression in your communities. Act in ways that thwart carceral logics in your responses to conflict and harm as well as your day-to-day relations with others. Remember, there are no prisons or cops in olam ha-ba (the world to come).

6. Make art and display it in public. Draw, paint, or write a colorful sign about your dreams, your hopes for a better world, or to celebrate something that you love about this one. It doesn’t matter if you don’t think of yourself as an artsy type. If you can, get together with others to do this; share art materials, space, and ideas. Wheat paste (or wallpaper paste or glue) your finished work in public—somewhere you and others will see it when going about your daily lives. You’ve now made a material change to your surroundings. It will make people smile. It will make people feel less alone. It will make visible your resistance as well as visions. It also won’t last forever. Nothing does. You can always make more.

7. Take concrete steps to build relationships beyond borders and strengthen global solidarity with those who share your values. Here are a few starting points. Learn a new language and schedule mutual practice sessions with others studying your language; such skills will likely also prove useful to aid those at increased threat of being targeted. Reach out to other people (or collectives, projects, etc.) in other parts of the world who you share affinity with—Jews and Muslims, dispossessed and displaced people, anarchists and queers, and so on—and see if there’s anything you can collaborate on. Seek out the stories of people who fought or fled authoritarian regimes in the past and present; learn from their experiences, and engage in discussions about our current challenges and a diversity of tactics to address them.

8. Learn new skills, share them, and help others learn new skills toward everything we need and desire — everything for everyone, and what’s more for free. Learn to be a medic, facilitator, birth and death doula, electrician, filmmaker, mediator, writer, researcher to dig up information for your local antifascist crews, and on and on. Learn how to stop bleeds, plant gardens, squat and/or build houses, purify water, craft zines, sew clothing, repair cars, use a chain saw, make composting toilets, or cook for crowds. Learn how to aid folks in finding refuge, calming their nervous systems, setting up digital security, getting hormones, and so much more.

9. Feel your emotions. Do not sublimate them. Feel them and remember that this connects us to everyone who has ever despaired. Feel them with others. Set up peer support networks, a weekend-long emotional care clinic or daylong emotional aid skills share, or something as simple as social spaces where you can find others, sip herbal tea, and reciprocally warm each others’ hearts, even if temporarily.

10. Learn about and begin to practice alternative decision-making structures and group processes that have served those who got shit done in the past. Practice good processes that are cut from the cloth that the Zapatistas refer to as buen gobierno (good governance, or self-governance). Learn about Zapatista autonomous communities, Chéran, Rojava, and many other examples of self-governance, past and present, as inspiration as well as horizons to work toward.

11. Gather and distribute free N95/KN95 masks and COVID tests as a baseline toward building a more generalized harm reduction crew that can gather and distribute, for example, Naloxone, fentanyl test strips, clean needles, condoms, and lube. Normalize COVID, other health protections, and additional ways of taking reciprocal care of each other. Go to outdoor events (or mask up for indoor ones) to table and share pamphlets on collective COVID safety and harm reduction.

12. We have a long history of fighting fascism, states, and policing, including as embodied in a rich tradition of anti-authoritarian Jewish songs. Sing “Daloy Politsey/Polizei” (down with the police) at your next prison noise demo or Palestinian solidarity action. Start a study group and find inspiration in those stories—and then act on them. Join in fascist watches and cop watches, or start them in your neighborhood or city. Prepare forward for community self-defense, which can come in many shapes and sizes.

13. If you care for a child or children, work with one or many other caregivers to create a mutual aid group if there isn’t one already! Distribute multilingual flyers at pickup and drop-off spots for school, day care, or local playgrounds in order to find other caregivers to involve. Plan weekly or biweekly meetups at whatever space kids usually hang out (such as a park), and share needs and resources.

14. Revive the concept and practice of kassi, the mutual aid funds/networks that used to keep neighbors afloat and supported in eastern European shtetls. Borrow from your own ancestral traditions/histories of mutual aid to build real-life community by strengthening relations with your neighbors and comrades for the days and years to come.

15. Take time to mourn your losses and grieve your dead—as inseparable from fighting and organizing for the living; as part and parcel of mending the world and ourselves. Set up temporary and ongoing public altars. Paint murals to honor lost friends and comrades. Lean on the deep wisdom of grief rituals that have sustained life for millennia, such as saying Kaddish for the dead or doing shiva after a loss. Make rituals part of your resistance, queering and self-organizing them in collectivity with others. Take those rituals out into your community—by a river, on a street corner, at a DIY space or radical bookfair, during a forest defense or as a direct action.

16. Feed people for free. Look for a Food Not Bombs or Coffee Not Cops chapter or similar non-hierarchical mutual aid project near you, get in touch, and join in collecting ingredients for, cooking, and/or serving a meal. If there’s nothing in your area, organize a free picnic; put up posters and encourage everybody to come—and optionally, bring a dish. Talking to the people you share the food with is important; do this if you can. Notice the moment when someone comes to understand that food can be good and free and shared without restrictions, obligations, eligibility criteria, or expectations; this means that things don’t have to be the way they are.

17. If a friend or someone you know is having suicidal thoughts and reaches out to you, offer to drop everything and be present with them. Small acts of peer support can make an enormous difference; think of yourself as a “tourniquet” for them when they most need it. You can hold space for them, for instance; don’t make it about you or act scared but instead simply allow them to share feelings, especially without fear of the cops being called. Or keep them company and help look after their basic needs that day. Or let friends and other people you trust know in advance that they can call you in these kinds of situations, and that you’ll take a weapon away from them for as long as needed if they ask.

18. Organize a stoop or porch sale with a few other households, or even a regular stoop or porch sale, and use the funds to cover material needs for solidarity efforts, such as abortion or bail funds, or for gender-affirming surgery or aiding folks during a rent strike. Ask yourself: What time and materials could I easily donate that would have an exponential effect and allow me to meet and organize with friends and neighbors in my community? Rather than a personal responsibility or charity, fundraising becomes a way of building deeper networks of care and connection.

19. Engage in play with others as a gateway to imagining other worlds and experimenting with getting there while cultivating camaraderie and goodwill. Hold game nights. Invent your own versions of group “sports” such as capture the flag, tag, and soccer, and gather folks in a park to make riotously merry. Self-organize a queer Purim spiel or other DIY theatrics, and simply be silly (and/or use your performances to make fun of the social order and dream up ways it might tumble). Add playfulness to your banners, events, organizing, and actions.

20. Slow down. Heed Jewish wisdom: days and hours of rest are sacred. Heed disabled wisdom: your work is completely irrelevant to your worth! Your ancestors began weaving unfucked social fabrics and burning down fucked-up ones before you were a glimmer in their eye. Descendants to come will be weaving and unfucking and burning still. What can we even weave with only weak threads connecting us? Trust takes years. Any faster, and conflict rends our fabric like kri’ah, the Jewish ritual act of tearing cloth in mourning. So come fascism or liberation: weave slow, take sabbaticals, feast on kugel, and sing with your comrades down by the river.

This zine is a communal effort, with advice gleaned from the following Jewish anarchists: alice, asher, cat, chanaleh, cindy, cindy barukh, hannah, jhaavo, lilli, mazel, scarab, simcha, and vicky.