Eight Days in Palestine

I’m back in Jordan after eight days in Palestine. I was in Palestine as part of a delegation to be in solidarity with and learn from those engaged in Palestinian liberation. We visited and had dialogues with Palestinians and Israelis in Bethlehem, Hebron, Jerusalem, Nablus, Ramallah and Sderot. We sat, listened to and spoke with Christians, Jews, Muslims and non-believers. We went to the Gaza border.

I get paid to talk about the political, military, and economic. The questions I asked, the notes I took, and the lenses through which I viewed the last eight days in Palestine were geopolitical. Of course, human reality and experience are never removed or divorced from those subjects; they are those subjects. Many in the governments, media and think tanks in DC, London, Brussels, et. al., forget or forsake that wisdom – a good explanation for how ruinous, counter-productive and failed Western foreign policy is.

What I just wrote, so pseudo-intellectually in that previous paragraph, is pablum.

What matters is that just two days ago, I shook hands with a man, Hassan Abu Nasser, who lost 130 members of his family in one single Israeli airstrike in Gaza. You’ve never felt so helpless as shaking such a person’s hand. Unless, of course, you are the one whose bloodline was nearly wiped out. I don’t know what else to say about it.

Hassan Abu Nasser (on left). Photo: Matthew Hoh.

Representatives from civil society groups we met with believe the death toll from the genocide in Gaza is between 100,000 and 200,000. Nearly all I spoke to in Palestine spoke of Gaza with a cold and numb tenor and tone, the affect of accepting a cruel and debauched reality.

In the West Bank, according to UNRWA, since October 7th, 780 Palestinians have been killed, 174 children among them. Settlers have killed an additional 21 Palestinians. There have been more than 3,500 attacks and incidents from settlers, many of them beatings and burnings of agriculture and homes. American-supplied Israeli rifles and bombs have wounded more than 5,000 Palestinians in the last 13 ½ months. Notably, there have been more than 100 airstrikes; airstrikes had not happened in the West Bank in more than 20 years. 18 of the 168 killed by Israeli warplanes and drones have been children. Before October 7th, the Israeli military gunned down and killed, on average, more than one Palestinian a day. In the first ten months of 2023, Israeli soldiers murdered nearly 50 children in the West Bank. Yet, many in the US believe history started on October 7th, 2023.

We cannot compare to Gaza, nothing can, but the violence against Palestinians in the West Bank is at its highest levels in more than 20 years and worsening.

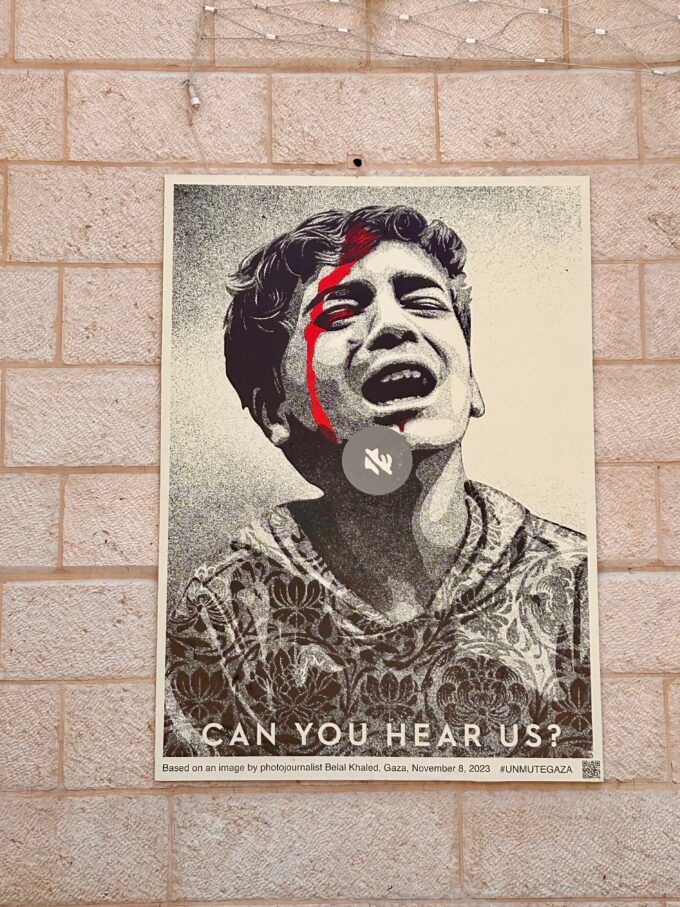

#UNMUTEGAZA campaign poster in Ramallah. Photo: Matthew Hoh.

It matters that we sat with Fakhri and Amneh in a trailer next to a demolished home in Jerusalem. Their home and 15 others have been destroyed this year in their neighborhood of Silwan to make way for Israeli settlements. Their children and grandchildren had lived with them. That was the home where Fakhri was born. Now he and Amneh live defiantly in a trailer on that land, next to their home’s rubble and the desecrated trees, their children and grandchildren scattered and gone. The Israeli government served a $10,000 bill to pay the costs of their home’s destruction. If Fakhri doesn’t pay, he’ll be arrested and his bank account seized. A demolition order has been received for the trailer they live in now.

Fakhri and Amneh in the trailer that sits next to their demolished home in Silwan, Jerusalem. Photo: Matthew Hoh.

Fakhri and Amneh are attacked at night. The trailer has been raided by soldiers and settlers, their possessions destroyed, Fakhri arrested. Not once or twice, but continuously, most auspiciously, the day Trump was elected. They came at 3am. Their son was beaten. They took Fakhri. Seven homes in the neighborhood were demolished on US election day; anyone willing to wager that was a mere coincidence? More than 100 homes in Silwan have pending demolition orders. 1,500 people live in them.

Since 1947, Israel has demolished 173,000 homes and structures in the West Bank. In 2023, nearly 1,400 buildings were razed. Demolition orders have increased 400% since January. In Jerusalem alone this year, 183 structures have been demolished, 33 in Fakhri and Amneh’s neighborhood. According to UNRWA, over the last 13 months, 5,000 Palestinians have been displaced from home demolitions, Israeli military operations and settler attacks in the West Bank. Coupled with the terrorism of the Israeli state through its American-financed military and settlers, the home demolitions are the means of ethnically cleansing the West Bank in preparation for eventual annexation. Most understand that October 7th gave Israel its best opportunity for ethnic cleansing, genocide and annexation in decades.

What’s left of Fakhri and Amneh’s home. Photo: Matthew Hoh.

Fakrhi speaks to us, Amneh doesn’t.

They cannot sleep. They expect the soldiers and settlers every night. Fakhri says, more than once, he is physically and mentally tired and sick.

“We live by paying fines and penalties, and spending time in jail. We have no hope, no sumud; nothing is sustaining us…only trying to keep our kids alive”, he says. It’s a hopelessness and exhaustion I heard throughout Palestine, most especially from those with children. I have witnessed the famed steadfastness of the Palestinians, and I have heard testimonies of radical acts of hope. Yet, I saw a fracturing of spirit and a fatalistic acceptance of reality I had not known before. More than one father told me what he wants is only to get his children to safety. 80 years of apartheid, annexation and annihilation will take their toll.*

Countless representatives of governments, international organizations and NGOs have visited Fakhri and Amneh. I sat in the same spot on their couch where Hans Wechsel, the US Embassy’s Chief of Palestinian Affairs, sat. [It should be noted that Wechsel’s two previous postings before taking over Palestinian Affairs in Jerusalem were advising US generals and directing Middle East counter-terrorism operations. Such a militarized and imperial view he brought into their home.]

Of their many high-ranking visitors, Fakhri says: “They are all liars.”

I didn’t hear anything more true during my nine days in Palestine.

*Israel’s strategy of breaking Palestinian resistance through terror and brutality may work on individuals and specific families, but overall their occupation and subjugation will encounter only deepening resistance. For those who want a historical example, I recommend watching The Battle of Algiers.

Of all of the people and places of these last nine days in Palestine, what matters most to me, what makes me break down sitting on this hotel bed in Madaba, the first time I have cried this week over Palestine, is the mother’s eyes I looked into in Ramallah. I’ve previously written and spoken of such eyes, specifically in Palestine. I’ve seen it in Afghanistan, Iraq and the US as well, mothers’ eyes clouded with the betrayal of it all – humanity, life, God – and their bodies besieged with a pain whose depths cannot be comprehended until a part of it transfers to you when you hold them.

Layan Nasir is a 24-year-old Palestinian Christian woman. I note her faith because many in the US and the West are unaware that Christians endure Israel’s apartheid, annexation and annihilation equally with Muslims. A student at Beirzeit University, Layan, has been held without charge for eight months. Her family has no idea why she was arrested, no explanation has ever been given, and if there was, certainly no evidence would be offered. They have not seen or heard from her. In December, again without explanation or charge, Layan’s detention can be extended.

Layan Nasir. Photo: social media. Being held indefinitely without charge is called administrative detention. In this manner, more than 5,500 Palestinians in the West Bank are held in Israeli military prisons, including more than 350 children. Nearly 100 other women are in prison with Layan. In total, more than 12,000 Palestinians from the West Bank are in Israeli prisons, more than at any point since the First Intifada, which ended 31 years ago. Four imprisoned college students from Nablus are among those who actually have charges. As related to us by their friends at An-Najah University, the Israeli army arrested the four boys for posting about Gaza on Instagram. They have been in prison for four months now.

In Gaza, thousands upon untold thousands of Palestinians have been kidnapped, detained, tortured and executed in Israeli prisons. This week, we learned that more than 310 doctors and nurses in Gaza have been detained, tortured and executed since October 7th. 1,000 more Palestinian doctors and nurses have been murdered by American-supplied bullets, bombs, shells and missiles, many in the hospitals and healthcare facilities where they cared for the sick, wounded and dying.

Palestinian life in East Jerusalem and the West Bank is entirely under Israeli military control. Arrests, trials, with a 99.7% conviction rate, and prisons are all military. Palestinians live under more than 16,000 Israeli military laws and regulations – nothing else matters. The Oslo Accords’ demarcation of the West Bank into areas A, B and C is practically and ultimately meaningless. Such is occupation.

Layan’s mother, Lulu, believes her daughter is well. That’s what she said to us. I want to believe her, but I cannot. The documentation from the UN, human rights groups, including the Israeli human rights group B’T Selem, journalists, and Palestinian testimony tells us otherwise. Israel conducts mass, deliberate and systematic torture, including rape and sexual abuse against Palestinian prisoners. That didn’t start after October 7th; it has been Israeli state policy since Israel’s inception in 1948 – there’s even a Wikipedia page devoted to it.

Lulu Nasir, Layan’s mother. Photo: Matthew Hoh.

The night Layan was taken from her parents’ home, a soldier pointed his weapon at Lulu and said: “be quiet or we will shoot you.” When her father tried to protect his daughter, a rifle was put in his face. That was the last they saw Layan.

Lulu’s final words to our delegation were: “My only daughter. She is my sister, my daughter, my everything.”

If for no reason other than I met this woman and saw her pain, knowing that Layan is only one of more than 12,000 held and tortured in Israeli prisons, I ask every one of you to contact your governments and demand her release. They will most assuredly do nothing, especially if you are an American. But for a mother and to be in solidarity with all Palestinians, I ask you to speak out for Layan.

Ofer Prison in the West Bank. The sign reads “Together we will win this war”. Only Israelis will see that sign as Palestinians are forbidden. How many thousands of Palestinians are held and tortured behind those walls I do not know. Photo: Matthew Hoh.

It is important for people to travel to Palestine to be in solidarity with the Palestinian people. I say this for two reasons.

First, it allows us to stand in defiance and dissent against our government’s policies.

The second and more important is that it seemed as if every Palestinian we met with told us how important it was for people to come to Palestine. The solidarity shown to them means everything to them. It tells them they are not alone and not forgotten. It offers some protection for the Palestinians as well, as the Israeli military and settlers may be less likely to attack and harass Palestinians if international representatives are present. However, in the last year, the restraint shown by the Israeli military, border police and settlers towards internationals has greatly diminished.

This originally appeared on Matthew Hoh’s Substack page.