Scholar Molefi Kete Asante discusses the radical origins of Black History Month and how it confronts cultural hegemony.

By George Yancy ,

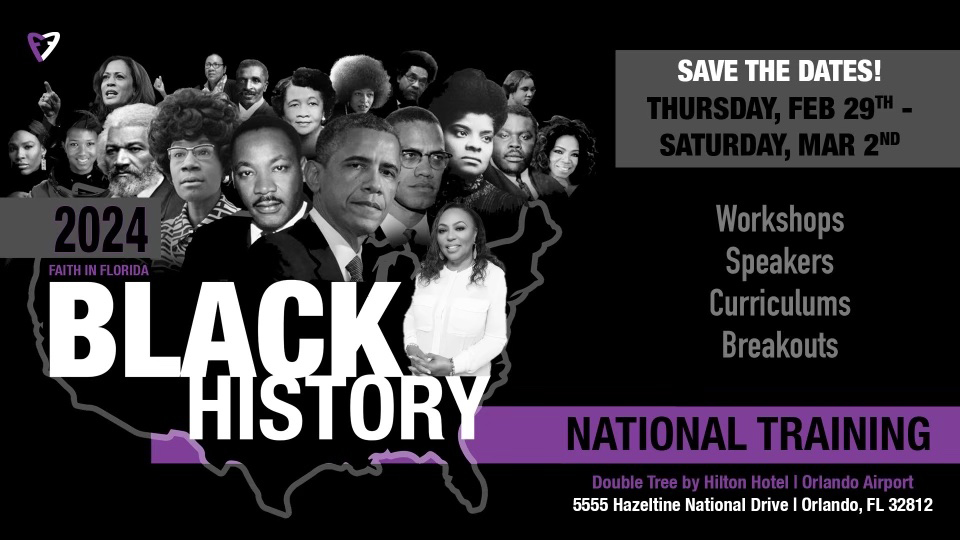

In February 1926, the Black historian and scholar Carter G. Woodson established Negro History Week, which later became known as Black History Month. In 1915, along with others, Woodson also helped to establish the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, and, in 1916, he started the Journal of Negro History. By 1933, Woodson’s powerful book, The Miseducation of the Negro, was published.

Woodson was a Black intellectual who fought to have the history of Black people told. At the time of his book, Woodson understood that Black people were being miseducated, inculcated with egregious ideas about Black “inferiority” and indoctrinated to believe that they were historyless. He understood that a key part of white supremacy involves the attempt to control the very thoughts of Black people and thereby their actions, arguing that this domination strategy is aimed at producing a situation in which white people “do not have to tell [Black people] not to stand here or go yonder. [They] will find [their] ‘proper place’ and will stay in it.” Hence, for Woodson, the education of Black people necessarily entailed the interrogation of white ideology and mythology that passed itself off as “knowledge.” Education for Black people was designed to liberate and decolonize their minds and generate political action.

When I think about our current celebration of Black History Month, I wonder if Woodson would approve of how this month is being practiced. Is our current approach to this month radical enough in relation to Black knowledge production? To address this theme and others, I reached out to the prolific scholar Molefi Kete Asante, professor in the Department of Africology at Temple University, who has published over 100 books, most recently, The Precarious Center, or When Will the African Narrative Hold? The interview that follows has been lightly edited for clarity.

George Yancy: What do you think Carter G. Woodson would say about how Black History Month is recognized and celebrated in the U.S.? I am worried that, like MLK Day, Black History Month will be stripped of moments and Black figures in history that are deemed “too radical.”

Molefi Kete Asante: Carter G. Woodson was a visionary; he would have visualized an African American population well educated and capable of educating fellow citizens about the achievements and accomplishments of African people. He would say that Black history is American history, and that the celebration of Black history is a profoundly American event. Yet Woodson would not think that merely celebrating was enough; he would wish for an action agenda that would see African American history taught in all public schools because it is the glue that helps students explain social, political and economic discrepancies.

RELATED STORY

INTERVIEW |

RACIAL JUSTICE

Black Existentialism Brings Philosophy to Bear on Our White Supremacist World

Black existentialism isn’t just about suffering — it is also about affirmation.

By George Yancy , TRUTHOUTFebruary 21, 2024

As to what is radical, no one in our history who has added to the victories over micro- and macro-aggressions needs to be avoided in Black history. It is not just the figures who have been praised by whites that should be honored, but those that whites have shunned such as Nat Turner, Marcus Garvey, Assata Shakur, Maulana Karenga, Bobby Seale and Angela Davis. In addition to those who have been outside of our gaze, there are those who have worked like Fred Gray, MLK’s lawyer, who spent a lifetime attacking all of the vestiges of segregation that he could find in the American South. Gray contributed to civil rights by giving us the practical tools to fight against all forms of discrimination based on race.

We know that the far right (typically, white) bathe in the perpetuation of white lies. They distort our history, and water down its complexity. If history helps to define the spirit and existential vibrancy of Black people, then an attack on Black history is an attack on the lives of Black people. What is it about Black history — its content, its function, its potential — that frightens the hell out of the far right?

Black history challenges cultural hegemony and makes visible that which was deliberately or ignorantly made invisible; in other words, all that we know about African Americans today is the results of a demanding African American insistence that our history be available to everyone.

Carter G. Woodson devoted his entire life to the mission of corrective history about African Americans. With a singular emphasis on the significance of knowing what Africans had done, he was certain that kernels of knowledge about Africa and African American history would transform the way we saw ourselves. He was correct, because almost every Black person who has accomplished something important can point to models, examples and events that inspired them.

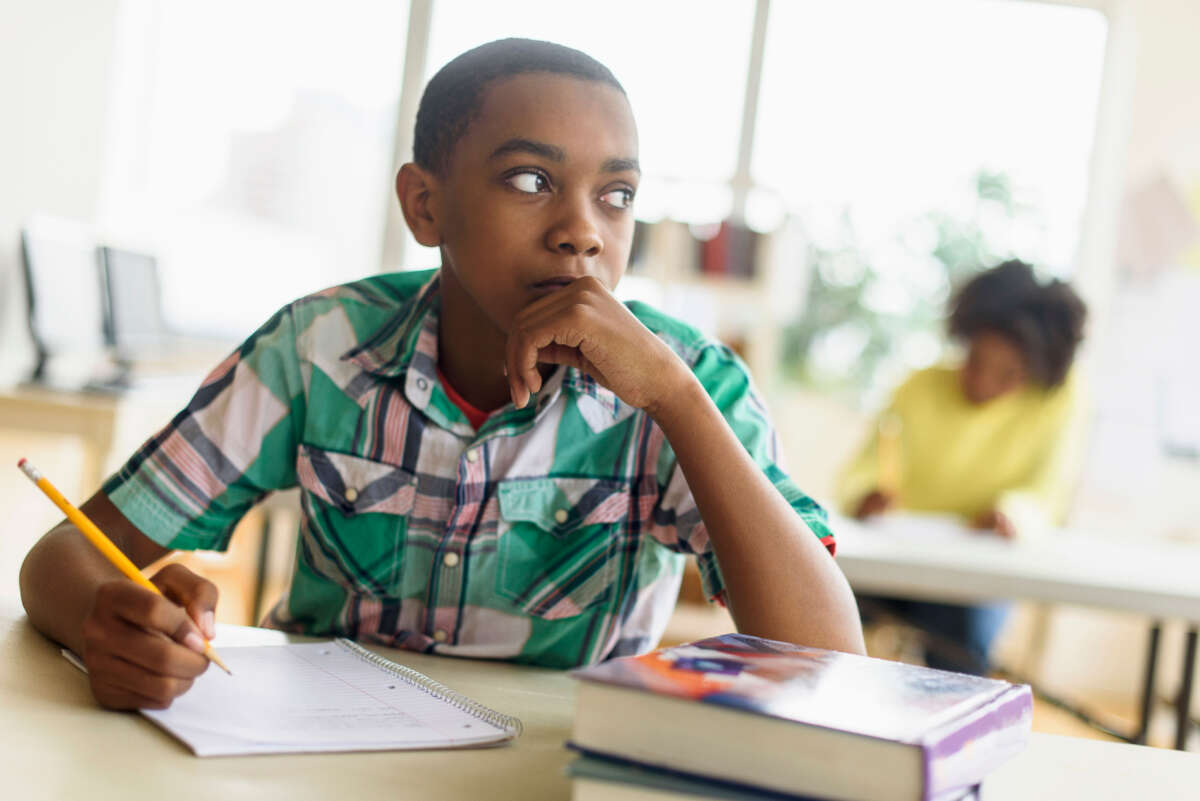

Young people who want to achieve something in science, art, artificial intelligence, architecture or culture can discover a bountiful field of African inspirations. This worries the far right because it means that Black people are no longer seeing themselves on the plantation that had been designed to minimize African people to enforce the illusion of white supremacy.

The aim of the far right is not so much a philosophical attack on African Americans (as in critical race theory; or diversity, equity and inclusion) as it is a cultural attack on African people themselves. In a strange way, our Blackness represents the origins of civilization, even beyond that, the beginning of our species, Homo sapiens. Consequently, any progressive social, economic or political project supported by African Americans could be a target of attack. Black people are no longer slinking back away from intellectual confrontation; we are confronting those who threaten our beingness with historical knowledge, wisdom and the assertion of a common humanity. Our aim as human beings is to fight to allow others to be human beings.

Black history challenges cultural hegemony and makes visible that which was deliberately or ignorantly made invisible

I really appreciate the profundity of how you characterize the aim of Black people, and how that aim is expansive and existentially inclusive. As we know, there are many ways that Black people can celebrate Black History Month. What would you recommend? I am especially interested in what you think needs to be emphasized and discussed in ways that have been overlooked. This brings us back to the theme of a more radical way of recognizing the purpose of Black History Month.

I think we should emphasize the nobility of people who have continued to succeed in a tough arena where our achievements have been minimized, ignored or disbelieved. Thus, it is persistent courage that is at the core of our history. Almost every Black community has individuals or groups who have made our history remarkable. Each town, city or community can identify some local figure or figures to serve as markers of persistent courage. It does not have to be material success or athletic prowess, but it could be a schoolteacher who rose to a task of providing space for children to learn history, values, and to receive cultural grounding.

Although MLK Day has taken on the idea of a national day of service in many cities, Black History Month has never had a specific action plan except to provide children with books on African Americans, information about African cultures, and classes and workshops about famous Black people. This is useful and necessary. What I propose for the month is “A Month of Awareness” where every day, those who want to celebrate learn something new for each day. Woodson put several projects and institutions in the service of Black history. He established the Associated Publishers, organized the Association for the Study of African American Life and History and wrote books for all ages. Our task is to make Woodson live in our daily activities by demonstrating awareness of who we are in the context of American and world history.

Children must be taught that the 300 or more African ethnic groups that were enslaved in the Americas came from a long history of civilization. Imhotep, the builder of the first pyramid was an African man. An African woman, Sobekneferu, was the first queen to rule a country in history. Almost all of the skills necessary for human survival were conceived and practiced and in Africa by humans long before migration out of Africa happened for Homo sapiens.

As you’ve demonstrated, Black History Month is certainly about education. What, for you, are the aims of education for Black people? And how might Black History Month resonate in the hearts and minds of Black people beyond February?

Education is different from training and ought to provide students with context, reason and knowledge. Without history, there is no context for students to understand what they learn. This means that reasoning is incomplete, and their knowledge is not a badge of achievement, but a weight around their necks. It is not alarmist to say that education, as a public system, has not always been our friend; indeed, the statistics of the condition of African American education suggest that education has often systematically robbed Black children of motivation, creativity, cultural identity and assertiveness. This means that children often leave school more damaged psychologically and culturally than they could or would, had they remained at home.

What I would love to see happen in the next iteration of Black History Month is a connection to a Pan African spirit. I have found people in Colombia, Brazil, Canada and Mexico, alongside people in the Caribbean and on the continent of Africa who have been inspired by the persistent and determined example set by African Americans to assert a common, nonhierarchal humanity.

At the current time, most schools treat Black History Month as a time for special emphasis on Black achievements, and there is nothing wrong with this idea; it was one of the wishes of Woodson. However, a more positive idea, now that we have the attention of the education system in many areas, is to integrate African American history and culture in every subject area in every classroom by inserting a fact or factoid in every lesson plan. Once this is practiced in any large urban district, it will catch on in others and be deemed a success. Every action takes political will and moral courage, without which it is impossible to succeed.

Beautifully stated, Molefi. I would like to end with a famous quote by Frederick Douglass, whose very birthdate has been erased by the white people who enslaved him and stole that part of his history: “This struggle may be a moral one, or it may be a physical one, and it may be both moral and physical, but it must be a struggle. Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.”

GEORGE YANCY is the Samuel Candler Dobbs professor of philosophy at Emory University and a Montgomery fellow at Dartmouth College. He is also the University of Pennsylvania’s inaugural fellow in the Provost’s Distinguished Faculty Fellowship Program (2019-2020 academic year). He is the author, editor and co-editor of over 20 books, including Black Bodies, White Gazes; Look, A White; Backlash: What Happens When We Talk Honestly about Racism in America; and Across Black Spaces: Essays and Interviews from an American Philosopher published by Rowman & Littlefield in 2020.