Dalit Scientists Face Barriers in India’s Top Science Institutes

Despite decades-old inclusion policies, Dalits are systematically underrepresented in science institutes in India. Why?

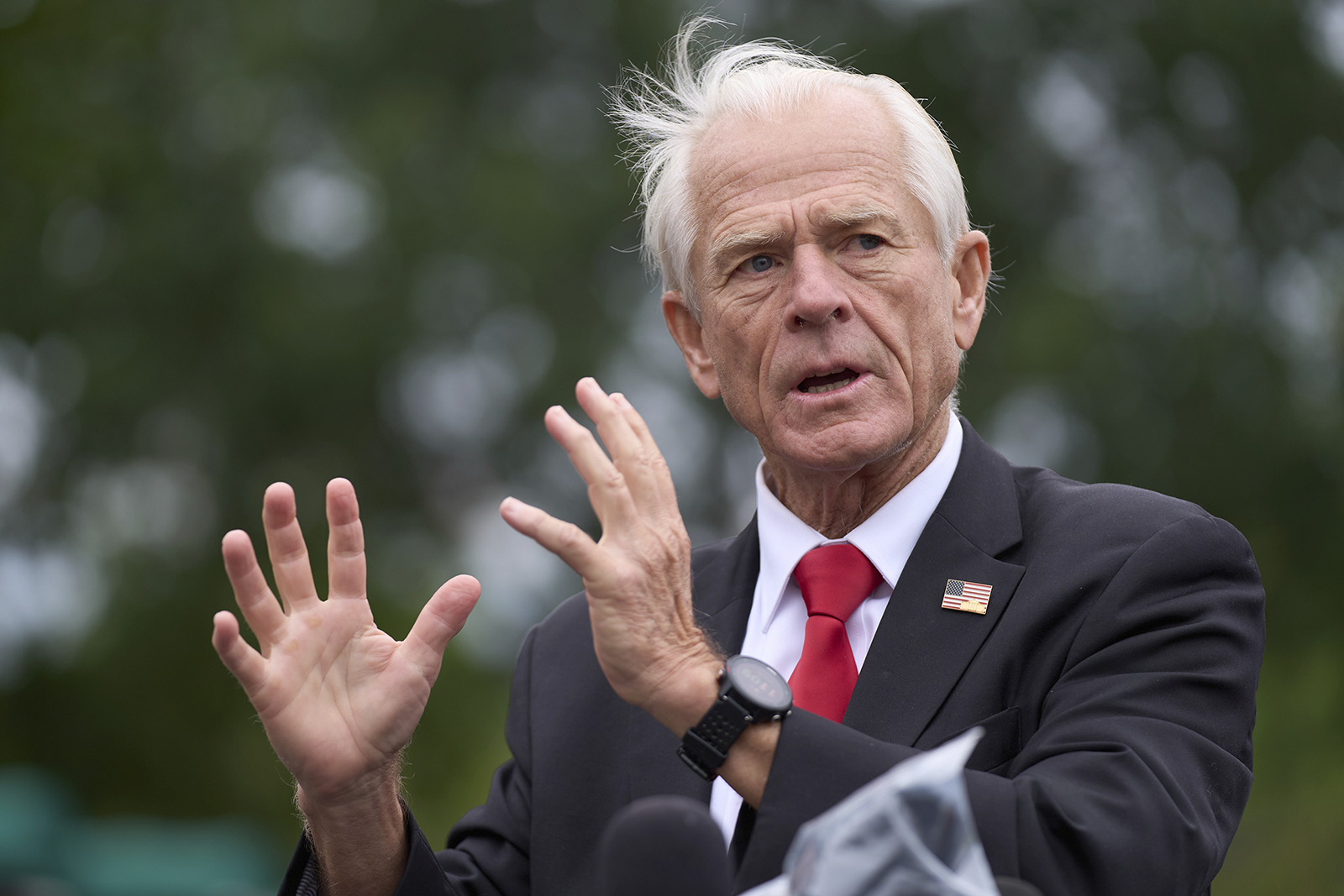

Top: Dalit researcher Rajendra Sonkawade has advocated for the rights of lower-caste scientists like himself. But he believes his advocacy has hampered his career. “I paid the price for speaking up,” Sonkawade said.

Visual: Ankur Paliwal for Undark

LONG READ

IN THE SUMMER OF 1976, 26-year-old Raosaheb Kale entered the School of Life Sciences at New Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University, alongside about 34 other incoming doctoral students. At the time, a committee of teachers at the school would review the students’ records and assign each to a Ph.D. supervisor to mentor them through graduate school. When the school posted the list of assignments, Kale scanned the piece of paper: Every single student, he said, had been matched with a supervisor, except for him.

“Nobody wanted to take me,” recalled Kale, who is now 71, sitting on his apartment’s balcony in Pune, in western India.

Kale knew why his name was missing: In his class, he was the only one from the Dalit community — formerly known as the untouchables. The teachers didn’t want to supervise Dalits, Kale said, because they perceived that Dalits “won’t perform well.”

Historically, Dalits were considered so low that they fell outside the caste system, a rigid social hierarchy described in ancient Hindu legal texts. Brahmins (priests) occupied the top of the pyramid, followed by the Kshatriyas (warriors), Vaishyas (traders), and then Shudras (artisans) at the bottom. Today, caste, which is defined by family of origin, remains an ever-present reality in Indian culture, and functions somewhat similarly to race in America.

Growing up in the drought-prone Beed district of western India, Kale shared a mud-walled, tin-roofed house with his parents and four younger siblings. Like other Dalits, his parents were unable to own land and barred from entering temples. In his village, Dalits were assigned various jobs such as sweeping streets, supplying firewood, delivering messages, and picking cotton. In return, they received grains, leftover food, or, on very rare occasions, one rupee for a day’s labor — well below a livable wage.

When Raosaheb Kale, a member of the Dalit caste, entered graduate school in the 1970s, he was the only student the school did not match with a Ph.D. supervisor. “Nobody wanted to take me,” Kale said. In Indian culture today, caste, which is defined by family of origin, functions similarly to race in America. Visual: Ankur Paliwal for Undark

The village was peaceful as long as Dalits followed the Hindu caste hierarchy. “You know your limits,” Kale recalled. “The moment lower caste crosses the limit, ignorantly or otherwise,” anything can happen, he said. Once, when Kale was a kid, he recalled holding the hand of a higher-caste boy to cross a river in the village. A furor erupted. An older upper-caste person from the village warned parents of both boys that such close contact should never happen again.

Against staggering odds, Kale excelled in academic science. He fought his way through the upper-caste dominated School of Life Sciences, became its dean, and received a prestigious award for his contributions to radiation and cancer biology research. In 2014, he completed his tenure in one of the top academic posts — vice chancellor of a university — in India.

But his story remains rare. In 2011, around 17 percent of India’s population, which now totals over 1.3 billion people, were Dalits, who are officially referred to as “Scheduled Castes” in government records. Caste discrimination is illegal, and India’s reservation policy — a form of affirmative action that has been around since 1950 — currently mandates that 15 percent of students and staff at government research and education institutes, with some exceptions, come from the Dalit community. But records obtained by Undark under India’s Right to Information Act from some of the country’s flagship scientific institutions, along with data from government reports and student groups, reveal a different picture.

At the elite Indian Institutes of Technology in Delhi, Mumbai, Kanpur, Kharagpur, and Madras, the proportion of Dalit researchers admitted to doctoral programs ranged from 6 percent (at IIT Delhi) to 14 percent (at IIT Kharagpur) in 2019, the most recent year obtained by Undark. At the Indian Institute of Science, or IISc, in Bengaluru, 12 percent of researchers admitted to doctoral programs in 2020 were Dalits. And at the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research — a major government research institution — of the 33 laboratories that responded to Undark’s data requests, just 12 met the 15 percent threshold.

The numbers are even lower among senior academics. IIT Bombay, in Mumbai, and IIT Delhi had no Dalit professors at all in 2020 — compared with 324 and 218 professors, respectively, in the General Category, which includes upper-caste Hindus and some members of religious minorities, like Muslims. (In India, the term “professor” refers to senior-ranking positions and does not include assistant or associate professors.) IISc had two Dalit professors and 205 General Category professors in 2020. None of the department heads at IISc were Dalit last year. And five out of the seven science schools of Jawaharlal Nehru University did not have a single Dalit professor.

“You know your limits,” Kale recalled. “The moment lower caste crosses the limit, ignorantly or otherwise,” anything can happen, he said.

Similar disparities exist in other professions in India; Dalits face continued discrimination and violence from upper-caste people across the country. But researchers who study casteism in science say that even as Dalits have mobilized for their rights, they have encountered distinctive barriers in scientific institutions, which remain especially resistant to reservation policies and other reforms. At a time of growing attention to inequities in global science, those barriers leave Dalits systematically underrepresented in the major research and academic institutes of the world’s largest democracy.

Undark sent repeated interview requests to the directors of IISc and five leading IITs. Only one responded, but declined to comment. In interviews, some upper-caste researchers said that finding qualified Dalit researchers can be difficult. “When you’d sit in the interview board, you will find out yourself,” said Umesh Kulshrestha, the dean of Jawaharlal Nehru University’s School of Environmental Sciences, who is upper caste. Some Dalit candidates “can’t answer even easy questions,” he said, later adding that he has “some good quality Dalit researchers” in the school. Several other upper-caste researchers simply denied that caste prejudice was common in Indian science, saying that they didn’t believe in caste.

But interviews with Dalit scientists and scholars show a different picture — one in which systematic discrimination, institutional barriers, and frequent humiliation make it difficult to thrive at every step of their training.

KALE WAS BORN in 1950 — three years after India became free from British rule, and the same year India’s constitution came into force. That constitution abolished untouchability and declared caste discrimination illegal. It also introduced reservation policies in public sector jobs, politics, and education for marginalized communities, including Dalits and Indigenous groups known as Adivasis. By the 1970s, the government had settled on the 15 percent quota for Dalits that’s still in place today.

Caste discrimination, however, continued. Sitting on his balcony in Pune, Kale described how casteism followed him on his path to higher education. As a small child, he studied in a public school with only one teacher. When the teacher died of cholera, the school closed. Kale walked to a nearby village every other Sunday to meet the headmaster of a bigger school there and ask when he’d get a new instructor. Eventually, the headmaster, who was Dalit, invited Kale to join his school and stay with him. “He really treated me like his son,” said Kale. He would later dedicate his Ph.D. thesis to the headmaster.

When Kale was in the sixth grade, and attending a new school, a teacher invited him over to take special classes at his home. When Kale arrived, the teacher’s wife was going to offer him some food in a “tasla” — an iron pan that laborers use to carry mud — instead of a plate. Kale refused both the meal and the classes.

But he kept getting grades so good that he eventually won admission to Milind College of Science — part of a group of colleges founded by Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, a Dalit leader and lawyer who is sometimes compared to Martin Luther King Jr.

In the late 1940s, a couple of years before Milind College opened, the Indian government began planning to set up a network of exclusive technical institutes to train engineers and scientists who would help build a new India. The first branch of the Indian Institute of Technology, or IIT, opened in 1951 near Kharagpur, and the government soon termed the schools “institutions of national importance.” At the time, a government committee described advanced scientific research as the work of a “few men of high caliber,” the Harvard University anthropologist Ajantha Subramanian writes in “The Caste of Merit,” a study of caste and engineering education in India. IITs were highly selective, and upper-caste Indians quickly dominated their ranks, despite the official reservation policies.

In the early 1970s, when Kale was applying to graduate schools, he didn’t seriously consider IITs, which he said looked like “closed spaces.” Instead, he enrolled in Marathwada University, in Maharashtra state. Part of a wave of new, more democratic state institutions, the university had become a fertile ground for student movements. (It has since been renamed in honor of Ambedkar.) Kale decided to study chemistry, partly because he thought that could get him a job as a chemical engineer in the fast-industrializing country. As the eldest sibling, Kale wanted to support his family as soon as possible. But at same time, he said, “I had an internal desire to get as much education as I can and the highest honorable degree.” So instead of heading straight into the workforce, he began considering doctoral programs.

Kale used some of his saved-up scholarship money to buy a train ticket to New Delhi, where he would take the Ph.D. entrance exam for Jawaharlal Nehru University, or JNU, which attracted students for its interdisciplinary approach, and where Kale’s battle against institutional casteism would begin.

AFEW WEEKS after the JNU faculty failed to match Kale with a Ph.D. supervisor, they offered him a mentor in a different field from the one he hoped to study. He began contemplating what to do next. He learned that Araga Ramesha Rao, a radiation biology researcher, had worked at a cancer research institute in Mumbai, a field he wanted to pursue. Kale managed to arrange a meeting. After several discussions Rao, who has since died, agreed to supervise the aspiring scientist. He did so, Kale said, despite the advice of an upper-caste colleague who urged Rao to avoid mentoring a Dalit student. (Kale was careful to clarify that various upper-caste colleagues, like Rao, supported him throughout the years.)

Alok Bhattacharya, who later joined the school as an associate professor, and belongs to an upper caste, said experiences like Kale’s are not uncommon, and that the only form of discrimination he has observed in his career is that the “lower caste” students faced difficulty in getting a supervisor: “They are the last ones to be picked.”

Kale completed his Ph.D. in 1980, and the school hired him as an assistant professor the next year. But Kale had to wait 17 years to become a professor — much slower than some of his upper-caste peers.

RELATED For India’s Caste-Based Sewer Cleaners: Robots?

Kulshrestha, the dean of the School of Environmental Sciences at JNU, and Pawan Dhar, a professor and former dean of the School of Biotechnology, both said that delays in promotions are common for researchers, irrespective of caste. But Govardhan Wankhede, a Dalit sociologist and former dean of the School of Education at the Mumbai-based Tata Institute of Social Sciences, believes that Dalits tend to face more delays, something he said he has experienced firsthand. According to Dhar, there’s little data analysis on caste-based discrimination in promotions — a gap, he said, that he hopes future research will address.

As Kale was waiting on his promotion, he was also waiting to get a lab to advance his research on making radiation therapy more effective in cancer treatment. While administrators gave most of his upper-caste peers their own laboratory space, Kale said, he worked out of a small corner office with broken furniture. When a senior professor vacated his lab to move to a bigger one, Kale declared the space his own. The ploy worked. “You have to have decency for some time, but not beyond certain limit. If it is your right, you have to snatch it,” he said. “We cannot wait.”

Over the years, Kale held several positions, including dean of students and head of the equal opportunity office at JNU. He would invite Dalit students from his and nearby villages to stay with him, helping them navigate the admissions process for universities. Kale also became the chairperson of the Indian Institute of Dalit Studies in New Delhi, and served on a government committee on Dalit and Adivasi reservation in universities.

Despite his success, all through his career, Kale said, he has feared just one thing — making mistakes. He and several Dalit researchers described experiencing a constant internal pressure to prove themselves in institutions dominated by upper-caste researchers who think Dalits don’t deserve to be there. “If I do a mistake, it is not my mistake,” said Kale. Instead, he said, it would be labeled “the mistake of the community.”

IN THE LATE 1990s, when Kale became a professor at JNU, he sat on a committee to select junior researchers at the Nuclear Science Center, about a mile away from the university in New Delhi. Among the candidates was a Dalit researcher named Rajendra Sonkawade. “He was the best among the lot,” recalled Kale. Sonkawade got the job.

Like Kale, Sonkawade had grown up in the western state of Maharashtra and planned to become an engineer. After high school, he applied to some engineering colleges but couldn’t score high enough to gain admission. He enrolled instead at Marathwada University, where he excelled in physics.

As Sonkawade worked his way through graduate school, the Dalit movement gained momentum in Indian politics, and the Bahujan Samaj Party, a pro-Dalit political party, rose to power in India’s most populous state, Uttar Pradesh.

“You have to have decency for some time, but not beyond certain limit. If it is your right, you have to snatch it,” Kale said. “We cannot wait.”

During the same time, though, India witnessed new opposition by upper-caste Hindus against the reservation policies. In 1990, the Indian government announced that it would implement a commission’s recommendation to expand reservation policies to include Other Backward Classes, an official designation for various other marginalized castes. Adding to the existing quotas, the new policy meant that 49.5 percent of seats were now, at least officially, reserved for lower-caste candidates. “Merit in an elitist society is not something inherent,” the commission had argued in its report, “but is the consequence of environmental privileges enjoyed by the members of higher castes.”

That “ignited a firestorm,” Subramanian writes in “The Caste of Merit.” “Upper-caste students took to the streets, staging sit-ins; setting up road blockades; and masquerading as vendors, sweepers, and shoe shiners in a graphic depiction of their future reduction to lower-caste labor.” More than 60 upper-caste students, many of whom said they were protesting the new policy, died by suicide.

The tension was palpable in educational and research institutes. At the Nuclear Science Center — later renamed the Inter-University Accelerator Center, or IUAC — Sonkawade began to study radiation safety. Often, he said, he would hear some of his upper-caste colleagues say that Dalits were incompetent. Frustrated, he waited for the standard new-employee probationary period to end. Then Sonkawade worked with Dalit and Adivasi researchers in the institute to form an association to represent their rights.

“We became more active with our demands,” said Sonkawade, thumping his palm on the table in his office at Shivaji University, in the west Indian city of Kolhapur, where he now teaches physics. On the wall to his right were some photographs, including one of Ambedkar, whom Sonkawade calls his role model.

After forming the association, Sonkawade began to push IUAC to set up a special committee to tackle Dalit and Adivasi issues to ensure implementation of the reservation policy — something required of government-funded institutes, but which the school had not established. His group also asked for the representation of marginalized communities in the governing boards of the institute.

Described by Kale as “the best among the lot” of junior researcher candidates, Rajendra Sonkawade was hired in the 1990s at what is now called the Inter-University Accelerator Center, where he began advocating for the rights of lower-caste researchers. In his office at Shivaji University, a portrait of Dalit leader Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar hangs on the wall next to an image of Mahatma Gandhi. Visual: Ankur Paliwal for Undark

While Kale was tactful in navigating institutional casteism, Sonkawade was more confrontational. His advocacy soon brought him into conflict with the IUAC administration, several of his colleagues said. “He became very unpopular,” Debashish Sen, a scientist at IUAC, recalled. Others felt, Sen said, that Sonkawade was operating out of his own self-interest rather than for the betterment of his community.

In interviews, many of Sonkawade’s colleagues described him as hard working. But, around the mid-2000s, the scores on Sonkawade’s annual performance reports — essential for promotion — began to drop. Sonkawade was overlooking his responsibilities in the lab, said Devesh Kumar Avasthi, a senior scientist who was one of the evaluators of Sonkawade’s performance. But Satya Pal Lochab, who oversaw the lab in which Sonkawade worked and also participated in the evaluations, said that his “anti-establishment activities” affected his scores. Eventually, the lagging scores delayed a promotion.

Dinakar Kanjilal and Amit Roy, both former directors of IUAC, said the delay in promotion had nothing to do with caste. In national labs, “I don’t see anybody bother about caste,” said Kanjilal, who is upper-caste. “They see your contribution.”

Feeling harassed, Sonkawade left and joined Shivaji University. Even at his new post, he kept pushing IUAC to recognize that it had owed him a promotion. Although IUAC eventually yielded — and Sonkawade said he won partial backpay. By that point, he said, the promotion “wasn’t of any use” for his career. “The whole system was against me,” he said. “I paid the price for speaking up.” An IUAC employee who used to field discrimination complaints confirmed seeing many cases where Dalits received performance review scores just a few decimal points below the requirement for promotion. The person requested anonymity, fearing reprisal from the institute.

Between 2018 and 2020, Sonkawade was invited to interview for the position of vice chancellor at three universities in Maharashtra, and for the director’s position at IUAC. In at least three of those four cases, an upper-caste person was chosen.

After his promotion was delayed due to lower scores on his annual performance reports, Sonkawade joined Shivaji University, where he teaches physics today. A senior scientist who participated in the evaluations said that Sonkawade’s “anti-establishment activities” affected his scores. Visual: Ankur Paliwal for Undark

EVEN AS DALIT researchers like Sonkawade and Kale recount fighting against casteism, many upper-caste researchers describe themselves as caste-blind, or beyond caste — a phenomenon, critics say, that has made it more difficult to address ongoing disparities in top scientific institutions.

In 2012, social anthropologist Renny Thomas joined a chemistry laboratory at the Indian Institute of Sciences to study caste dynamics at the institute, arguably India’s most elite science university. That year, he interviewed 80 researchers, and later observed a cultural festival celebrated at the institute. Again and again, Thomas found, Brahmin researchers denied that caste existed in their lives or on the campus. “Caste!?? Oh, Please! I have nothing to do with caste,” one molecular biologist from a Brahmin family told Thomas, according to a paper he published last year. “It never registered in my mind.”

Such claims aren’t limited to academic science. In a 2013 paper, University of Delhi sociologist Satish Deshpande argued that for many upper-caste Indians, caste is “a ladder that can now be safely kicked away,” but only after they convert those high-caste privileges into other forms of status, such as “property, higher educational credentials, and strongholds in lucrative professions.” Many Dalits, Kale said, would also like to forget their caste. But upper-caste people, he added, “don’t let us.”

“The whole system was against me,” Sonkawade said. “I paid the price for speaking up.”

Interviews with young Dalit scientists, along with a growing body of academic work, detail the obstacles Dalits still face on their path through scientific training. Those barriers begin early: Just getting into science and engineering education has been a challenging and uncommon choice for Dalit students in the first place, according to Wankhede, the educational sociologist. “Science education is very expensive. Highly inaccessible,” he said. Students pay higher tuition rates for science courses than in other areas, because they are required to take additional classes to do experiments. And to keep up with their coursework, science students often pay for instruction in pricey private academies called coaching institutes, something many Dalit families cannot afford.

For those Dalits who make it into elite scientific institutes, cultural barriers remind them of the caste divide. During his time at IISc, Thomas found that his lower-caste and Dalit sources identified reflections of upper caste culture throughout the institute. Thomas focused on the Carnatic music concerts that Brahmin students organized. Traditionally, Carnatic music, a type of classical music, has long been the domain of Brahmins in southern India. In one instance at IISc, after the singer finished her song, the Brahmin audience continued singing, showing their familiarity with the art form, writes Thomas. But such events alienated researchers who were not Brahmin. One saw Carnatic music as a “symbol of domination” and said he preferred “folk songs and songs of resistance by Dalit reformers.”

“The mindset remains extraordinarily Brahminical in these elite institutions,” said Abha Sur, a historian of science at Massachusetts Institute of Technology who has written about caste and gender in Indian science. That mindset, she added, tacitly aligns itself with caste hierarchy: “There is implicit devaluation of people that continuously erodes their sense of self.”

In a predominantly Dalit neighborhood of Mumbai, people gather around a statue of Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar to read their newspapers. Ambedkar, a Dalit leader who founded a group of colleges, is sometimes compared to Martin Luther King Jr. To many, the casteism Ambedkar fought against still exists today. Visual: Ankur Paliwal for Undark

Undark spoke with eight early-career Dalit science researchers who declined to be identified, fearing retaliation from their institutions or harm to their careers. Most described receiving humiliating reminders about using reservation quotas from upper-caste students and teachers, which implied they weren’t there on their own merit. Many also said their institutes make no effort to create awareness about casteism, and just overlook it. “It seems that the untouchability still exists, but in a different form,” said one student, who’s pursuing a Ph.D. in engineering at IISc.

These tensions sometimes bubble into the public eye. In 2007, for example, a government committee found widespread discrimination and harassment against Dalit and Adivasi students at the All India Institute of Medical Science in New Delhi. The humiliation and abuse by upper-caste students was so bad, the committee reported, that Dalit and Adivasi students had moved to the two top floors of their hostels, seeking safety together.

In 2016, Rohith Vemula, a Dalit Ph.D. researcher at Hyderabad University, died by suicide. The press reported that discrimination at the university had contributed to Vemula’s death. His loss sparked outrage on several campuses across India and led to the formation of more student organizations like Ambedkar Periyar Study Circle, which offer support to Dalit and other oppressed castes.

In a copy of one 2019 discrimination complaint leaked to Undark, a Dalit Ph.D. student at IISc describes experiencing several instances of caste discrimination. In one incident detailed in the report, the student’s supervisor didn’t let him enter a lab where cells are grown in a carefully controlled environment, saying he was “not clean.” Later, the supervisor justified his actions by saying that the student sometimes scratched his skin. The report alleges that the student’s supervisors also kept delaying a critical exam required within two years of starting a Ph.D., saying the student had not gathered enough data. But, the student said in the complaint, other students from the same lab had taken the exam with far less data. The student asked for a transfer to another lab, where he passed the exam and transitioned to a senior fellow position.

“It seems that the untouchability still exists, but in a different form,” said one IISc student.

Such formal complaints may be relatively rare. Akshay Sawant, an upper-caste member of Ambedkar Periyar Phule Study Circle, a student organization at IIT Bombay, said that discrimination cases remain underreported because students fear retaliation from their upper-caste supervisors. The special Dalit and Adivasi affairs committee at IIT Bombay received only one complaint between 2019 and 2020, which, as of May, was still being investigated. IISc received three complaints in 2020, of which two, as of late April, were unresolved.

Caste divisions occasionally spill over into scientific communities beyond India’s borders. Since the mid-1960s, for example, United States policies designed to incentivize the immigration of skilled STEM professionals have led hundreds of thousands of scientists and engineers — most of them upper-caste — to move from India to the U.S. In June 2020, California state regulators sued the technology company Cisco Systems, alleging that two upper-caste supervisors had harassed and discriminated against a Dalit employee. According to the complaint, one of the supervisors had disclosed the engineer’s caste to colleagues, telling them he had attended an IIT in India under the country’s reservation policy. The complaint also states the engineer was subjected to a hostile work environment and pay discrimination based on his caste. (The hearings have been postponed until September of this year.)

A 2016 survey by Equality Labs, a progressive Dalit civil rights organization, found that 67 percent of Dalits in the Indian diaspora in the U.S. reported facing caste-based harassment and discrimination in the workplace. In Silicon Valley, most of the Indians come from institutions “where caste discrimination is rampant,” Subramanian wrote in an email to Undark. “Therefore, the entry of caste discrimination into the American tech sector is not in the least bit surprising.”

WHEN KALE entered graduate school in the 1970s, there were no Dalit role models for him in science. Fifty years later, many early-career Dalit researchers say the same.

One early-career Dalit scientist willing to speak openly about her experiences is Shalini Mahadev, a researcher pursuing a doctorate in neural and cognitive sciences at the University of Hyderabad, one of India’s top-ranked universities. In an interview, Mahadev said she badly wants to see more senior scientists from her community, and to have teachers who can relate to the life experiences of students like her. “Having them in your classroom, in your research, in your lab is something else, because you are coming with so many anxieties, you know,” she said. “And you are feeling inefficient all the time.”

Mahadev is in her late 30s and grew up in Hyderabad. Her father, who was part of the first generation in his family to go to school, had received an engineering diploma — a specialized course shorter than an undergraduate degree — in order to get a job quickly. Her mother discontinued her studies after marrying young. The family had modest resources, and Mahadev remembers feeling intense pressure to study and perform. Her father told her that he has always lived with a gnawing feeling that he couldn’t study more, and that he didn’t want her to feel the same way, recalled Mahadev.

Early-career Dalit researcher Shalini Mahadev says she badly wants to see more senior scientists from her community.

Visual: Courtesy of Shalini Mahadev

After high school, Mahadev took a break to prepare for national examinations to become a doctor. Like many students in India, she turned to coaching institutes that help students prepare for the exam. The atmosphere in these institutes is extremely competitive. On her first day of classes, she said, teachers would ask Dalit students to stand up, while upper-caste students sat in their chairs. The teachers would tell the Dalit students that, even if they didn’t study hard or get great marks, they were likely to get admission in medical colleges because of reservation policies — unlike the upper-caste students who needed to study harder.

Standing in the class, Mahadev could feel the eyes of her upper-caste classmates on her. Teachers “are already making people hate me,” she remembers thinking. As demeaning incidents piled up, Mahadev said, she began avoiding going to the institute. Eventually, she decided she didn’t want to become a doctor. Instead, she chose to study biology, because she liked learning about genes. Later, she became fascinated with neurons. Today, she studies the connection between neurons and the sense of hearing in grasshoppers.

Reminders of caste shadowed her. On campus, she said, upper-caste people would assert their status in subtle ways — through what they wore, how they talked, even how they walked. At one point, when Mahadev was a junior research fellow, another fellow told her that science is not for poor people, she recalled. That broke Mahadev’s heart, because it also seemed true to her. In her view, historically, “science was only done by rich people,” she said — people who have the time and resources to pursue it. And for Mahadev, time often seemed scarce: Living in a neighborhood on the outskirts of Hyderabad, she spent four to six hours each day commuting via bus between her house and the university, until she could finally get a place in the university hostel.

Many elite institutes have resisted change. In April 2020, following growing criticism in Indian media about the low representation of marginalized communities at IITs, India’s Department of Higher Education formed a committee to suggest ways to implement the reservation policy. The committee, in its report, said that because few students from the “reserved category” receive Ph.D.s, few are available to be hired as teachers or researchers. The committee also recommended that IITs, as “institutes of national importance,” should be exempted from following the reservation policy in hiring teachers.

Support Undark Magazine

Undark is a non-profit, editorially independent magazine covering the complicated and often fractious intersection of science and society.