Kate Hairsine | Sertan Sanderson

Women's rights remain under threat in Gambia after parliament decided to postpone a vote on upholding the ban on female genital mutilation (FGM).

Female genital mutilation (FGM) remains illegal in Gambia — for now. A decision in Gambia's National Assembly on whether to overturn the ban on FGM has been postponed for at least three months.

The divisive issue led MPs to ask for more consultation on the matter, referring the bill to a parliamentary committee which will examine it for at least three months. The bill will then be returned to parliament.

According to the AFP news agency, hundreds of people were seen protested outside parliament on Monday, with most supporting a repeal of the ban on FGM.

The tiny West African nation had explicitly criminalized FGM, also called cutting or female circumcision, in 2015, making the practise punishable with up to three years in prison or a fine of 50,000 dalasi ($736 or €678), or both.

In cases where FGM causes death, the law calls for life imprisonment.

FGM involves the partial or total removal of the female external genitalia, often involving the removal of the clitoris or labia. It has no health benefits and is proven to harm girls and women in many ways.

The private bill to scrap the law outlawing FGM, which was proposed by individual members of parliament, argues that the current prohibition violates citizens' rights to practice their culture and religion.

Renewed debate around criminalizing FGM

The debate around FGM in Gambia flared up in mid-2023 after three women were convicted of the practise under the law. They were ordered to pay a fine of 15,000 dalasi or serve a year in jail for carrying out female genital mutilation on eight infant girls, aged between four months and one year. However, an imam paid the fines for all three women,

These were the first convictions under the law. Prior to this, only two people had been arrested and one case brought to court, according to UNICEF, and no convictions or sanctions had been handed down.

This is despite nearly three out of four girls and women, or 73%, having undergone female genital mutilation in Gambia, according to official figures.

Parliamentary reporter Arret Jatta told DW that she wasn't surprised that the pro-FGM bill has come before parliament, given the heated discussions in recent months:

"Almost all the National Assembly members are in support of the law being repealed, especially the female National Assembly members," she said.

Different interpretations of Islam

Most of the small African country's population are Muslim, and many believe that FGM is a requirement of Islam. The Gambia Supreme Islamic Council issued a fatwa (religious decree) last year, declaring FGM "one of the virtues of Islam."

However, Isatou Touray, former vice president and founder of the anti-FGM organization GAMCOTRAP, strongly refutes this interpretation.

"Who has the right to interfere in what Allah had created, and who has the right to define how a woman should look?" Touray told Gambian media organization Kerr Fatou.

Supporters of FGM meanwhile believe it can "purify" and protect girls during adolescence and before marriage.

"When it comes to the social aspect, they'll even tell you, 'Oh, it is to ensure that you stay a virgin because if you have the clitoris then … you would want to have sex,'" woman's rights advocate Esther Brown said in an interview on DW's AfricaLink radio program earlier in March.

Human rights violation

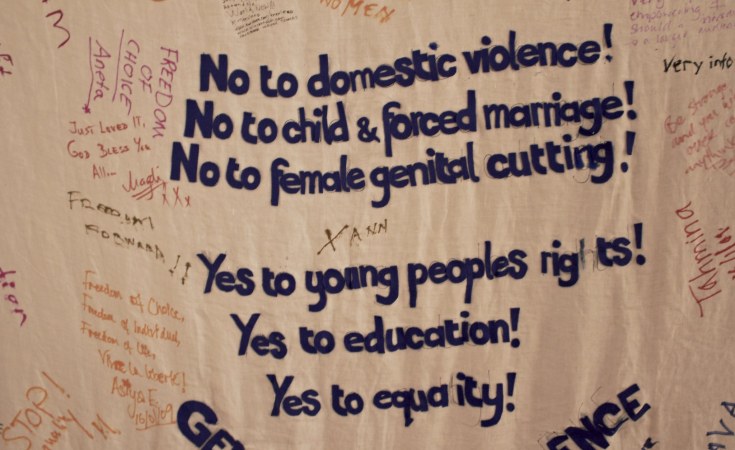

The practice of FGM is recognized internationally as a violation of the human rights of girls and women, finds the World Health Organization.

As well as severe bleeding, FGM can cause a variety of severe health problems, including infections, scarring, pain, menstruation problems, recurrent urinary tract infections, infertility and complications in childbirth.

One study on the health consequences of FGM in Gambia found women who were cut are four times more likely to suffer complications during delivery, and the newborn is four times more likely to have health complications if the mother has undergone FGM.

But for Fatima Jarju, an FGM survivor who sensitizes women in Gambia to the harms of the procedure, the ongoing debate on the issue is causing further damage to women's rights:

"I think it's a big setback ... looking at our human rights standards as a country and also the commitment from the government to protecting the rights of women and girls of this country," she told DW.

Legislation not always effective against FGM

The Gambia is among 28 sub-Saharan nations where FGM is practiced. Six of these nations lack a national laws criminalizing the procedure (see map below). The Gambia could soon join them.

Many anti-FGM activists stress, however, that legislation alone is insufficient to tackle FGM, especially when it lacks enforcement, as is the case in Gambia.

Rugiatu Turay in Sierra Leone, one of the six African nations without a law against FGM, has gained international recognition for her work combating FGM.

The strategies she uses include the development of rites of passage for girls that don't involve cutting, finding alternative livelihoods for the cutters and intense community engagement.

She isn't convinced that legislation is the best way to tackle the issue.

"Generally, in Africa, people make laws to satisfy their donor partners. But when it comes to implementation, they are not implemented," she told DW.

To change cultural attitudes, she says, more community-based initiatives are needed that involve everyone from regional chiefs, local headmen and religious leaders to the cutters and the mothers making decisions for their daughters.

"If every sector in our country speaks about the cut and the scar — and its consequences — I tell you, we will end FGM," she said.

Sankulleh Janko in Banjul, Eddy Micah Jr. and George Okach contributed to this article.

This article was first published on March 7, 2024 and was updated on March 19, 2024 to reflect the postponement of a vote to repeal the FGM ban.

Edited by: Rob Mudge

Issued on: 19/03/2024 -

Video by: Nadia MASSIH

Lawmakers in Gambia are debating on a repeal of the 2015 ban on the widely condemned practice of Female Genital Mutilation (FGM). Gambian activists fear a repeal would overturn years of work in the largely Muslim country to better protect women and girls as young as 5 years old. It can cause childbirth complications and have deadly consequences, yet it remains a widespread practice in parts of Africa. As Gambia lawmakers consider a repeal of the ban, under heavy pressure from powerful religious leaders, FRANCE 24's Nadia Massih is joined by renowned Gambian activist Jaha Dukureh, Regional UN Women Ambassador for Africa and CEO / Founder of the NGO “Safe Hands for Girls” providing support to African women and girls who are survivors of Female Genital Mutilation (FGM).

Gambian parliament debates bill to reverse ban on female genital mutilation

Issued on: