Image by Tim Dennell.

Recently, in an executive order, President Trump directed the removal of “improper, divisive, or anti-American ideology” from the Smithsonian Institution. That order was, in essence, an attempt to rewrite history on race and gender. One-hundred-and-one-year-old Colonel James H. Harvey, one of the last of the famed Tuskegee airmen of World War II, blamed Trump, saying, “I’ll tell him to his face. No problem. I’ll tell him, you’re a racist.” In addition, government websites began scrubbing African-American history, including in the case of the National Park Service eliminating a photo of the famed abolitionist Harriet Tubman and descriptions of the brutal realities of slavery.

Black people in America have often led change in this society because our humanity and our liberties were so long suppressed and denied.

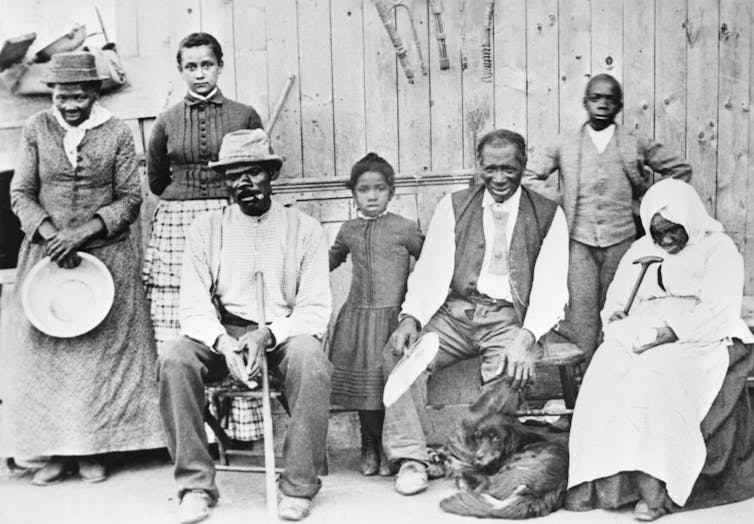

Black people in my family and community were, of course, descendants of the enslaved. In their presence (as I well remember), you could feel their closeness to that terrible time in our history. When that Smithsonian news came out, I thought about the killings, rapes, lynchings, breeding, and selling of Black people that was, for several hundred years, so much a part of life in the United States of America and that was, if Donald Trump had anything to say about it, no longer to be part of the true history of the United States. I didn’t have to be reminded of who I was or my status as a Black American that day, or of the history he’d like to wipe out, because I lived in the South in the 1950s and 1960s and racism and Jim Crow were then in my face every day of my existence.

So, let me tell Donald Trump a thing or two.

Long, long ago, in the course of my time in high school and college, I realized that Black people in the South were still dealing with a form of American fascism not so dissimilar from Apartheid in South Africa. At the time, Black southern activists were deeply engaged in transforming the structure of this society.

Such activism, I believed then and I believe now, began in 1619, the moment enslaved Africans were deposited in chains on American shores. Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass became two spokespeople for those who had lived as slaves. Both tried to change the attitudes of the wider public. Later, many others, including Ida B. Wells-Barnett, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Marcus Garvey, would continue the work to end the legacies of slavery and eliminate all aspects of racism. During my youth, the North similarly had strong spokespeople for racial equality in Malcolm X and Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. In the West, Cesar Chavez was organizing the United Farm Workers to improve the conditions of Latinos working in the fields of California and the Southwest. At the same time, the emerging American Indian Movement (AIM) and the Asian American movement were growing in a collective struggle against discrimination and racism.

Those organizations energized student movements nationwide through sit-ins and demonstrations and by getting arrested as they fought for civil rights. The Black Panther Party, the movement against the war in Vietnam, and the growing Feminist movement added thousands more actions to that struggle. Years later, such movements would also influence the development of the Black Lives Matter, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer movements and the National Domestic Worker Alliance.

My father always told me as a boy and later a young man: “Don’t go down to Alabama and Mississippi — those White-ass crackers down there don’t like Black folks.” But in 2019, I found myself in Montgomery, Alabama, the first capital of the Confederacy. All those years later, I could still hear my father’s voice ringing in my ears and had trepidations about being in that state with its racist history. I remembered the Montgomery Bus Boycott, demonstrations against White supremacy led by Martin Luther King, Jr., and young people in 1963, the water cannons and dogs used against Black children and adults, and racist Governor George Wallace’s attempt to block integration at the University of Alabama on June 11, 1963, saying: “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” I remember the horror of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham, Alabama, where four little girls were murdered by White racists.

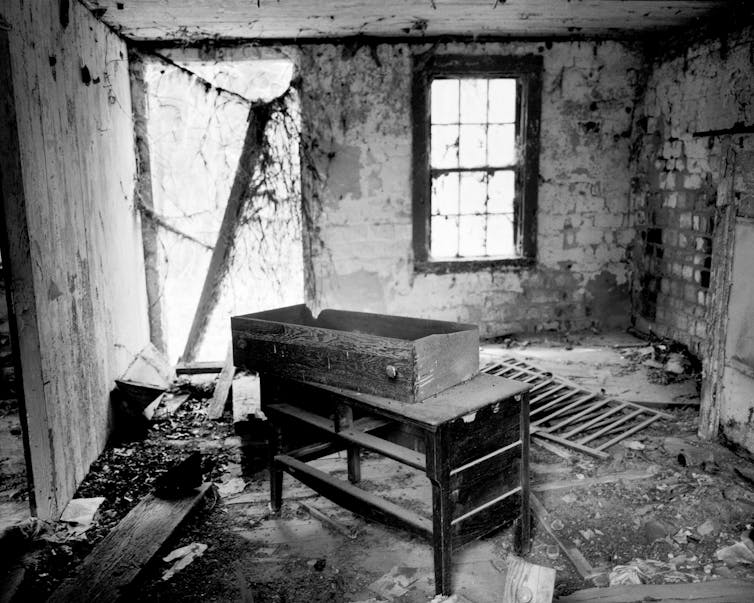

In February of 2019, I traveled to Montgomery with other board members of my son Khary’s social justice organization, The Brotherhood Sister Sol, to visit the Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice created by Bryan Stevenson, the activist, lawyer, and founder of the Equal Justice Initiative. At the Legacy Museum, visitors experience 400 years of American history that includes enslavement, racial terrorism, and mass incarceration. The National Memorial is the first institution of its kind dedicated to the legacy of the Black Americans who were the victims of the racial terror of lynching. (Four thousand four hundred of those lynchings have been documented in the post-Reconstruction era from 1877 to 1950 by the Equal Justice Initiative.)

That memorial includes 805 hanging steel rectangles representing each of the counties in the United States where lynchings took place. As I walked through them, I immediately went to those representing Lenoir County and Jones County, North Carolina, where most of my family was born and raised. One victim was listed in Lenoir County, Lazarus Rouse on August 1, 1916, and one, Jerome Whitefield, on August 14, 1921, in Jones County. I was informed by the Equal Justice Initiative that, during the Reconstruction period (1865 to 1876), nine other Black victims were lynched in those two counties. Four of them were killed in 1866 (their names unknown); the other five were Cater Grady, Daniel Smith, John Miller, and Robert Grady on January 24, 1869, and Amos Jones on May 28, 1869.

The Museum and Memorial proved a deeply overwhelming experience for me, a sudden rush of long-ago race history being imprinted in the deep recesses of my mind. For many of those on the visit that day, it was emotional, but as the only Black person in our group to have lived through segregation and Jim Crow, I found it a genuinely wrenching physical experience. And yet while I felt distinctly ill at ease, shaken by what I had seen at the museum and memorial, within hours I began to feel powerful for the part I had played once upon a time as an activist in the Civil Rights Movement. That activism, I suddenly realized, had made me a better, stronger person, and I was reminded that the 400 years of Black struggles for equal rights in this country had not only inspired the nation, but the world.

Authoritarianism and Racism

Today, racism in this country is still a central force that progressives are working to change. We are, after all, living in a period when authoritarianism, racism, and incipient fascism are all on the rise again and, of course, Donald Trump is giving all-too-vivid voice to the hate that goes with them.

In a New Yorker article in 2016, Nobel Prize winner Toni Morrison wrote of the existential place of race for Whites in America this way:

“All immigrants to the United States know (and knew) that if they want to become real, authentic Americans they must reduce their fealty to their native country and regard it as secondary, subordinate, in order to emphasize their whiteness. Unlike any nation in Europe, the United States holds whiteness as the unifying force. Here, for many people, the definition of ‘Americanness’ is color.”

At another point in that year of Trump’s first presidential victory, she added:

“On Election Day, how eagerly so many white voters — both poorly educated and the well-educated — embraced the shame and fear sowed by Donald Trump. The candidate whose company has been sued by the Justice Department for not renting apartments to black people. The candidate who questioned whether Barack Obama was born in the United States, and who seemed to condone the beating of a Black Lives Matter protester at a campaign rally. The candidate who kept black workers off the floors of his casinos. The candidate who is beloved by David Duke and endorsed by the Ku Klux Klan.

“William Faulkner understood this better than almost any other American writer. In ‘Absalom, Absalom,’ incest is less of a taboo for an upper-class Southern family than acknowledging the one drop of black blood that would clearly soil the family line. Rather than lose its ‘whiteness’ (once again), the family chooses murder.”

And the great James Baldwin in his classic 1955 analysis of race in America, Notes of a Native Son, wrote:

“No road whatever will lead Americans back to the simplicity of this European village where white men still have the luxury of looking on me as a stranger. I am not, really, a stranger any longer for any American alive. One of the things that distinguishes Americans from other people is that no other people has ever been so deeply involved in the lives of black men, and vice versa. This fact faced, with all its implications, it can be seen that the history of the American Negro problem is not merely shameful, it is also something of an achievement. For even when the worst has been said, it must also be added that the perpetual challenge posed by this problem was always, somehow, perpetually met. It is precisely this black-white experience which may prove of indispensable value to us in the world we face today. This world is white no longer, and it will never be white again.”

Many in this diverse nation have compelling stories to tell, generating energy to battle the reactionary right-wing efforts to roll back any progress that has been made in past decades. In my life, I have endured the hardships of racism, as have so many others. However, my family, community, and various forms of activism enabled me to survive.

Walking in the Shoes of Black People in History

It is critical, even in Donald Trump’s America, that our activism remain nonviolent, tactical, and practical. We can reflect on a momentous decision by Martin Luther King, Jr., James Bevel, Wyatt Walker, Fred Shuttlesworth, Ralph Abernathy, and other civil rights leaders in Birmingham, Alabama, in the spring of 1963. Out of desperation, they decided to use high school students in demonstrations there in what became known as “the Children’s Crusade,” recognizing that Eugene Bull Connor, the notorious segregationist commissioner of public safety in that city, would employ violence against them. And, of course, he did. He ordered dogs and water cannons turned on those demonstrations, saying, “I want to see the dogs work. Look at those niggers run.”

The very brutality of Bull Connor, seen across the country and the world on the TV news, generated tremendous support for the civil rights movement.

I suspect that King, Bevel, Walker, Shuttlesworth, Abernathy and the other civil rights leaders in Birmingham knew that using high school students involved enormous risk, but those students already lived under segregation and racism and were walking in the shoes of others who had been similarly courageous in the past and this, of course, would be their contribution to civil rights.

Wyatt Walker explained what he did by indicating that he made no apology for using such a tactic to reveal the racist brutality of the grim system of segregation to the whole nation. He said, “I had to do what had to be done.”

His words in their simplicity are how we must confront what is now happening in our country, too. We all must take risks to make this a more democratic land that respects all people. The action of those civil rights leaders in Birmingham is one example of Black history that must never be erased because it still inspires others to act.

At the time, of course, the actions of those young people confronting Bull Connor in Birmingham inspired many throughout the country. Two weeks later, on May 19, 1963, along with 15 other protesters, I demonstrated in front of the then-segregated Holiday Inn in Durham, North Carolina. We were confronted with a dangerous situation. The leader of our group was 19-year-old Joycelyn McKissick, a fellow student of mine and the daughter of Floyd McKissick, a local civil rights leader and lawyer hated by many Whites in the area. We could see into that Holiday Inn through its plate glass windows and observe cops walking around its lobby with billy clubs, keeping a watchful eye on us. If that wasn’t ominous enough, 15 feet from us were 10 White men with broom handles and baseball bats shouting, “Fuck the niggers! Fuck the niggers!”

Despite the obvious danger, we continued picketing and singing. Fortunately for us, the White thugs didn’t get a chance to go after us because of the courage of McKissick. Without any warning, she broke from the picket line, ran to the door of the lobby, pushed it open, and flopped down on the floor inside. The cops shouted, “Get that McKissick bitch!” They then began to beat her with batons.

After a few seconds, I pushed open that same lobby door intending to flop on the floor, too, but was met by police officers who started beating me with their batons and billy clubs as I backed up against a plate glass window. I was still standing, trying to block those clubs being swung at my head, when a 260-pound Black football player named Roy burst through the lobby doors shouting, “Stop it! Stop it!” and moved aggressively toward the police. The officers appeared startled and possibly even scared by his size. All of a sudden, miraculously enough, they stopped beating Joycelyn and me. All of the demonstrators were, however, arrested and marched off to jail along with 1,000 people from the sites of other demonstrations in Durham. The city jail couldn’t cope with more than 1,000 arrested demonstrators. So, though we were held overnight, we were released the following morning.

That confrontation with the police in that Durham Holiday Inn empowered me for the rest of my life. Those billy clubs striking my body strengthened my mind and convinced me that, sooner or later, we could indeed overcome segregation and Jim Crow. They caused me to be less afraid and more confident in mass demonstrations to come.

To me, that experience was a powerful tool for change and, looking back, I believe the size of those demonstrations and their public nature caused the police to be somewhat more restrained as time went on, although I was aware that there would be times in other settings when nothing would prevent serious injury or even death at their hands.

Today, the many compelling stories of those suffering in this increasingly diverse nation of ours — from immigrants to domestic workers to all the discriminated-against people I’ve mentioned in this essay — must be told. As we experience Donald Trump’s twenty-first-century version of White nationalism, how we dealt with that difficult past should help us remember that we lived through terrible times by confronting them and that we can do so again, even in the terrible Trump era.

This piece first appeared on TomDispatch.

View image in fullscreenHarriet Tubman in a photograph dating from 1860-75, provided by the Library of Congress. Photograph: Harvey B Lindsley/AP

View image in fullscreenHarriet Tubman in a photograph dating from 1860-75, provided by the Library of Congress. Photograph: Harvey B Lindsley/AP