CANNES QUEER PALM AWARD

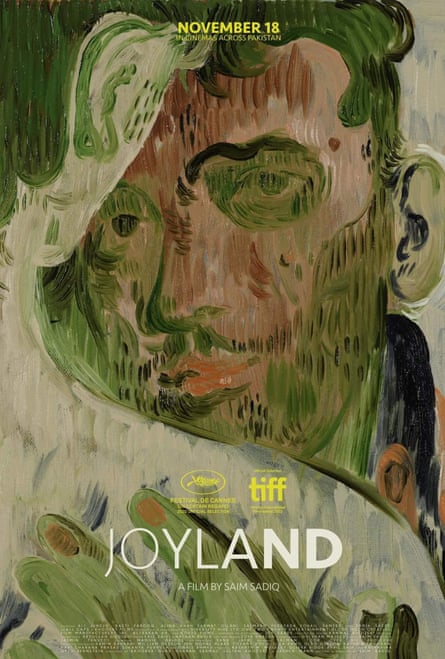

Saim Sadiq's Joyland wins Pakistan's first-ever Cannes honour with Un Certain Regard Jury PrizeThis is Pakistan's first-ever competitive entry at Cannes.

Joyland, a Pakistani movie featuring a daring portrait of a transgender dancer in the country, on Friday won the Cannes Queer Palm prize for best LGBT, “queer” or feminist-themed movie, the jury head told AFP. The film also won the Jury Prize in the Un Certain Regard segment.

Joyland by director Saim Sadiq, a tale of sexual revolution, tells the story of the youngest son in a patriarchal family who is expected to produce a baby boy with his wife but joins an erotic dance theatre and falls for the troupe’s director, a trans woman.

It is the first-ever Pakistani competitive entry at the Cannes festival where it is part of the Un Certain Regard segment that focuses on young, innovative cinema talent. Un Certain Regard is a competition focused on art-house films that runs parallel to the main competition, the Palme d'Or, which will be announced on Saturday.

“It’s a very powerful film, that represents everything that we stand for,” jury head, French director Catherine Corsini said.

“Joyland will echo across the world,” Corsini said. “It has strong characters who are both complex and real. Nothing is distorted. We were blown away by this film.”

Joyland beat off several other strong entries, including Close by Belgian director Lukas Dhont and Tchaikovsky’s Wife by Kirill Serebrennikov, both hot contenders for the Cannes Festival’s top award Palme d’Or which will be announced on Saturday.

Joyland left Cannes audiences slack-jawed and admiring and got a standing ovation from the opening night’s crowd.

The film stars Sarwat Gilani, Sania Saeed, Ali Junejo, Alina Khan and Rasti Farooq.“It felt like the hard work that people do, the struggles that we face as artists in Pakistan, they’ve all come to be worth it,” Gilani told Reuters on Tuesday after the standing ovation.

“It’s not just about a love story anymore. It’s about real-time issues, real life issues that we all go through,” she said. “Having a woman, a trans, represent that sector of the society, I think it’s a really good step in the direction where we can say we can write progressive stories.”

Here's what the international press has to say about Pakistani film Joyland

PUBLISHED 24 MAY, 2022

Cannes Review: Saim Sadiq’s Joyland — Deadline

"Joyland has a vivid sense of place, created not so much by its geographical backdrop as its characters. There’s an attention to detail in the rituals of daily life, whether it’s family celebrations or the rehearsals of the dance group. Mostly restrained emotionally, this packs an unexpected gut punch towards the end of the film, where it shifts focus to a deserving subject and drops another key character.

Presumably that’s meant to reflect the perspective of the protagonist, though it does leave some stories up in the air. But Joyland remains a thoughtful, well performed and engrossing drama set in a culture that’s shifting, and not always with ease."

To read more, click here.

Joyland: Film Review | Cannes 2022 — The Hollywood Reporter

"Joyland is a family saga, one that Sadiq uses to observe how gender norms constrict, and then asphyxiate, individuals. The Ranas feel trapped — by respectability, by family, by vague notions of honour. Bound by their duty to roles they quietly question, the members of this clan slowly suffer under the weight of obligation and expectations. What happens to them — individually and collectively — is a process that Sadiq’s film chronicles with aching consideration.

As Joyland heads toward its end, the film grows increasingly moving. Secrets and their attendant lies collapse under pressure. The weight of what’s left unsaid strangles interactions. The Ranas can no longer afford to be delusional — their survival depends on it."

To read more, click here.

Joyland Review: A daring queer Pakistani drama about desire — The Indie Wire

"The film’s 4:3 aspect ratio forces them into each other’s orbits in carefully composed tableus, and forces them to exist not just as individuals — whose joys and suppressed sorrows define them in equal measure — but as parts of a larger, fragile social fabric that feels like it could snap at any moment.

The frame moves slowly, if at all, but it always brims with physical and emotional energy; in Joyland, there’s always something in the ether, whether embodied by dazzling displays of light as characters move across stages and club floors, or by breathtaking silences as they begin to figure each other out, and figure out themselves."

To read more, click here.

Joyland: Cannes Review — Screen Daily

"Transgression becomes a means of liberation in Joyland, writer-director Sadiq’s assured first feature which explores the tensions within a Pakistani family enslaved by old-fashioned notions of gender and duty. Sadiq’s screenplay navigates a complex web of secrets and lies, pressures and prejudices to create a soulful human drama intent on challenging narrow minds. Said to be the first Pakistani film to play at Cannes, Joyland should make an emotional connection with audiences on the Croisette and far beyond."

To read more, click here.

Photo: Saim Sadiq/Instagram

Saim Sadiq’s Joyland, the first Pakistani film to be screened at Cannes, is riding a success high. The selection alone was enough of an achievement but the movie worked its magic and received a standing ovation at the premiere. And the international media has great things to say about it.

Described as a "daring" film, Joyland was picked for the Un Certain Regard category at the film festival. It is the story of an effeminate married man who falls for a transgender woman, which raises the tension between the conventional image his family wants him to fall into and the freedom he discovers to live a life of his choosing.

The movie has gained positive reviews by international publications. Here are some excerpts from those reviews.

Saim Sadiq’s Joyland, the first Pakistani film to be screened at Cannes, is riding a success high. The selection alone was enough of an achievement but the movie worked its magic and received a standing ovation at the premiere. And the international media has great things to say about it.

Described as a "daring" film, Joyland was picked for the Un Certain Regard category at the film festival. It is the story of an effeminate married man who falls for a transgender woman, which raises the tension between the conventional image his family wants him to fall into and the freedom he discovers to live a life of his choosing.

The movie has gained positive reviews by international publications. Here are some excerpts from those reviews.

Cannes Review: Saim Sadiq’s Joyland — Deadline

"Joyland has a vivid sense of place, created not so much by its geographical backdrop as its characters. There’s an attention to detail in the rituals of daily life, whether it’s family celebrations or the rehearsals of the dance group. Mostly restrained emotionally, this packs an unexpected gut punch towards the end of the film, where it shifts focus to a deserving subject and drops another key character.

Presumably that’s meant to reflect the perspective of the protagonist, though it does leave some stories up in the air. But Joyland remains a thoughtful, well performed and engrossing drama set in a culture that’s shifting, and not always with ease."

To read more, click here.

Joyland: Film Review | Cannes 2022 — The Hollywood Reporter

"Joyland is a family saga, one that Sadiq uses to observe how gender norms constrict, and then asphyxiate, individuals. The Ranas feel trapped — by respectability, by family, by vague notions of honour. Bound by their duty to roles they quietly question, the members of this clan slowly suffer under the weight of obligation and expectations. What happens to them — individually and collectively — is a process that Sadiq’s film chronicles with aching consideration.

As Joyland heads toward its end, the film grows increasingly moving. Secrets and their attendant lies collapse under pressure. The weight of what’s left unsaid strangles interactions. The Ranas can no longer afford to be delusional — their survival depends on it."

To read more, click here.

Joyland Review: A daring queer Pakistani drama about desire — The Indie Wire

"The film’s 4:3 aspect ratio forces them into each other’s orbits in carefully composed tableus, and forces them to exist not just as individuals — whose joys and suppressed sorrows define them in equal measure — but as parts of a larger, fragile social fabric that feels like it could snap at any moment.

The frame moves slowly, if at all, but it always brims with physical and emotional energy; in Joyland, there’s always something in the ether, whether embodied by dazzling displays of light as characters move across stages and club floors, or by breathtaking silences as they begin to figure each other out, and figure out themselves."

To read more, click here.

Joyland: Cannes Review — Screen Daily

"Transgression becomes a means of liberation in Joyland, writer-director Sadiq’s assured first feature which explores the tensions within a Pakistani family enslaved by old-fashioned notions of gender and duty. Sadiq’s screenplay navigates a complex web of secrets and lies, pressures and prejudices to create a soulful human drama intent on challenging narrow minds. Said to be the first Pakistani film to play at Cannes, Joyland should make an emotional connection with audiences on the Croisette and far beyond."

To read more, click here.