The Anthropocene Epoch, according to the Anthropocene Working Group of the International Union of Geological Sciences can be seen as having begun in 1945, at the end of the Second World War, or else in the 1950s. The stratigraphic markers most commonly referred to are radionuclides from hundreds of nuclear tests (and two nuclear bombings) and the development of plastics and petrochemicals. These developments are seen as having introduced a new “synthetic age.” Yet, this was also the time of the Cold War, the consolidation of global monopoly capitalism, and what is often referred to as capitalism’s “golden age.” The immediate post–Second World War period saw what environmental historians have referred to as the Great Acceleration of economic impacts on the earth to the point that planetary boundaries were being crossed, or in danger of being crossed. The Anthropocene Epoch can thus be seen as having its origins in the post–Second World War era, with monopoly capitalism at a high level of globalization as its principal driver.

Since each geological epoch is divided into geological ages, the first age of the Anthropocene Epoch can be referred to as the Capitalinian Age, describing its social origins, now dominating over the stratigraphic indicators of geological change. To designate the present as a particular age of the Anthropocene Epoch is to point to the temporary, historical character of the geological age in which we now reside, which will lead either to a new geological (and social) age, stabilizing the human relation to the earth, referred to here as the Communian, or to an end-Anthropocene extinction event resulting in the destruction of civilization and quite possibly humanity itself.

Indeed, the notion of the Anthropocene Epoch in geological history, expressing how human society, via capitalism, has proceeded to foul its planetary nest, has not been the revelation of a moment. Rather it can be seen as a product of a century-long discussion on the growing human impacts on the earth environment. In his Kingdom of Man in 1911, E. Ray Lankester, the leading British zoologist in the generation after Charles Darwin and a close friend of Marx, insisted that humanity as a result of capitalism had become a “disturber” of the ecology of the earth to such an extent that it undermined its own environment, giving rise to “nature’s revenges,” including new zoonotic diseases threatening humanity.

…For many, willing to resign humanity to its “fate,” the idea of a way out of our current dilemma, fundamentally altering society in order to avoid the socioecological chasm before us, will undoubtedly sound utopian. But utopia, a pun coined in the sixteenth century by Thomas More meaning both “nowhere” and “good place,” and therefore often seen as representing a kind of dream state or wishful projection into the future, loses its idealistic connotation in the context of a planetary dystopia where catastrophe, measured against historical precedents, has now become normal and threatens to become irreversible on a planetary scale, due to the inherent apocalyptic tendencies of the current mode of production. Under such circumstances, only the reconstitution of society as a whole, and thus of the human relation to the earth, holds any realistic hope for the future of humanity….

Marxism and the Universal Metabolism of Nature

…Beginning in the 1850s, based on the work of his close friend and comrade, the physician and scientist Roland Daniels, as well as on Justus von Liebig’s agricultural chemistry, Marx incorporated the notion of metabolism into his general analysis, introducing a conception of production (or the labor and production process) as constituting the “social metabolism” of humanity and nature.57 This conception was developed further in Capital, particularly in the analysis of ecological crisis, with the social metabolism standing for what we today call human-ecological relations. Here it is important to note that today’s ecosystem and Earth System analyses, and all form of systems ecology, have the concept of metabolism and flows of energy as their logical bases. Marx saw the social metabolism introduced by human beings in production as part of what he called the “universal metabolism of nature.”

In the mid-nineteenth century a soil crisis occurred in the new industrialized agriculture. Soil nutrients, such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, contained in the food and the fiber, sent hundreds and even thousands of miles to the new urban industrial centers where the population was now concentrated, ended up as pollution in the cities rather than being returned to the land, with the result that these vital “constituent elements” of the soil were lost to the soil. Marx saw this as a manifestation of a contradiction between the alienated social metabolism of capitalist production and the “universal metabolism of nature,” generating a “rift in the . . . social metabolism” or metabolic rift, which constituted the main structure of ecological crisis under capitalism.60 The triad of concepts of the universal metabolism of nature, the social metabolism, and the metabolic rift thus gave to Marx’s understanding of the ecological nature of production a complex, historically grounded conceptual structure, encompassing both Earth change and social system change, and their coevolution within the historical process. Exploring this problem in his later works, Marx engaged in extended analyses of ecological crises, or the metabolic rift, some of which were embedded in his ecological notebooks. Although Marx wrote of the metabolism of nature and society, this was not, as some critics have charged, a “dualistic” conception, since his emphasis was on how the social metabolism, rooted in changing relations of production, historically mediated the dialectical relation between humanity and earth.

Fundamental to this whole framework, emanating from classical historical materialism (in which Frederick Engels, as we shall see, also played a crucial role), is the notion that economic and environmental crises are two sides of a single coin associated with capitalism’s exploitation of labor, on one side, and its expropriation of people and the earth, on the other. Capitalism is not only an alienated economic regime, but also, as a precondition of this, an alienated ecological regime. Industrial capitalism requires as its basis, as Marx argued, the removal of the population from the land and thus from the organic means of production. It was the expropriation of the commons as well as whole populations on a world scale (including chattel slavery) that led to “the genesis of the capitalist farmer,” on the one hand, and the “genesis of the industrial capitalist,” on the other.62 This alienation from nature constituted the basis on which the alienation of human being from human being and between classes was established. This twofold alienation from nature and other human beings constitutes the source of capitalism’s continuing creative destruction of the conditions of existence of humanity itself…..

The origin of the “Western Marxist” tradition, in this sense, is usually traced to Georg Lukács’s criticism in History and Class Consciousness (1923) of Engels’s conception of the dialectics of nature. In footnote 6 of chapter one on “What Is Orthodox Marxism” Lukács inserted a short comment in which he stated:

It is of the first importance to realise that the method is limited here to the realms of history and society. The misunderstandings that arise from Engels’s account of dialectics can in the main be put down to the fact that Engels—following Hegel’s mistaken lead—extended the method to apply also to nature. However, the crucial determinants of dialectics—the interaction of subject and object, the unity of theory and practice, the historical changes in the reality underlying the categories as the root cause of changes in thought, etc.—are absent from our knowledge of nature. Unfortunately it is not possible to undertake a detailed analysis of these questions here.

This footnote by Lukács, consisting of less than ten lines altogether—the last line of which says, “It is not possible to undertake a detailed analysis of these questions here”—has often been exaggerated, treated as a full-blown critique, rather than a mere aside…

From Chapter 1:

…The remarkable discovery in the Soviet archives of Lukács’s manuscript Tailism and the Dialectic, some seventy years after it was written in the mid-1920s (just a few years after the writing of History and Class Consciousness), makes it clear that this critical shift in Lukács’s understanding, via Marx’s concept of social and ecological metabolism, had already been largely reached by that time. There he explained that “the metabolic interchange with nature” was “socially mediated” through labor and production. The labor process, as a form of metabolism between humanity and nature, made it possible for human beings to perceive—in ways that were limited by the historical development of production—certain objective conditions of existence. Such a metabolic “exchange of matter” between nature and society, Lukács wrote, “cannot possibly be achieved—even on the most primitive level—without possessing a certain degree of objectively correct knowledge about the processes of nature (which exist prior to people and function independently of them).” It was precisely the development of this metabolic “exchange of matter” by means of production that formed, in Lukács’s interpretation of Marx’s dialectic, “the material basis of modern science.”

Lukács’s emphasis on the centrality of Marx’s notion of social metabolism was to be carried forward by his assistant and younger colleague István Mészáros in Marx’s Theory of Alienation. For Mészáros the “conceptual structure” of Marx’s theory of alienation involved the triadic relation of humanity-production-nature, with production this way human beings could be conceived as the “self-mediating” beings of nature…. Lukács and Mészáros thus saw Marx’s social-metabolism argument as a way of transcending the divisions within Marxism that had fractured the dialectic and Marx’s social (and natural) ontology. It allowed for a praxis-based approach that integrated nature and society, and social history and natural history, without reducing one entirely to the other. In our present ecological age this complex understanding—complex because it dialectically encompasses the relations between part and whole, subject and object—becomes an indispensable element in any rational social transition.

Marx and the Universal Metabolism of Nature

…Since the Grundrisse in 1857–58, Marx had given the concept of metabolism (Stoffwechsel)—first developed in the 1830s by scientists engaged in the new discoveries of cellular biology and physiology and then applied to chemistry (by Liebig especially) and physics—a central place in his account of the interaction between nature and society through production. He defined the labor process as the metabolic relation between humanity and nature. For human beings this metabolism necessarily took a socially mediated form, encompassing the organic conditions common to all life, but also taking a distinctly human-historical character through production.

Building on this framework, Marx emphasized in Capital that the disruption of the soil cycle in industrialized capitalist agriculture constituted nothing less than “a rift” in the metabolic relation between human beings and nature. “Capitalist production,” he wrote,

collects the population together in great centres, and causes the urban population to achieve an ever-greater preponderance. This has two results. On the one hand it concentrates the historical motive force of society; on the other hand, it disturbs the metabolic interaction between man and the earth, i.e. it prevents the return to the soil of its constituent elements consumed by man in the form of food and clothing; hence it hinders the operation of the eternal natural condition for the lasting fertility of the soil. . . . But by destroying the circumstances surrounding this metabolism . . . it compels its systematic restoration as a regulative law of social production, and in a form adequate to the full development of the human race. . . . All progress in capitalist agriculture is a progress in the art, not only of robbing the worker, but of robbing the soil; all progress in increasing the fertility of the soil for a given time is progress toward ruining the more long-lasting sources of that fertility. . . . Capitalist production, therefore, only develops the technique and the degree of combination of the social process of production by simultaneously undermining the original sources of all wealth—the soil and the worker.

…In the twentieth century the concept of metabolism was to become the basis of systems ecology, particularly in the landmark work of Eugene and Howard Odum. As Frank Golley explains in A History of the Ecosystem Concept in Ecology, Howard Odum “pioneered a method of studying [eco-]system dynamics by measuring . . . the difference of input and output, under steady state conditions,” to determine “the metabolism of the whole system.” Based on the foundational work of the Odums, metabolism is now used to refer to all biological levels, starting with the single cell and ending with the ecosystem (and beyond that the Earth System). In his later attempts to incorporate human society into this broad ecological systems theory, Howard Odum was to draw heavily on Marx’s work, particularly in developing a theory of what he called ecologically “unequal exchange” rooted in “imperial capitalism.”

Indeed, if we were to return today to Marx’s original issue of the human-social metabolism and the problem of the soil nutrient cycle, looking at it from the viewpoint of ecological science, the argument would go like this. Living organisms, in their normal interactions with one another and the inorganic world, are constantly gaining nutrients and energy from consuming other organisms or, for green plants, through photosynthesis and nutrient uptake from the soil—which are then passed along to other organisms in a complex “food web” in which nutrients are eventually cycled back to near where they originated. In the process the energy extracted is used up in the functioning of the organism although ultimately a portion is left over in the form of difficult to decompose soil organic matter. Plants are constantly exchanging products with the soil through their roots—taking up nutrients and giving off energy-rich compounds that produce an active microbiological zone near the roots. Animals that eat plants or other animals generally use only a small fraction of the nutrients they eat and deposit the rest as feces and urine nearby. When they die, soil organisms use their nutrients and the energy contained in their bodies. The interactions of living organisms with matter (mineral or alive or previously alive) are such that the ecosystem is only lightly affected and nutrients cycle back to near where they were originally obtained. Also on a geological time scale, weathering of nutrients locked inside minerals renders them available for future organisms to use. Thus, natural ecosystems do not normally “run down” due to nutrient depletion or loss of other aspects of healthy environments such as productive soils.

As human societies develop, especially with the growth and spread of capitalism, the interactions between nature and humans are much greater and more intense than before, affecting first the local, then the regional, and finally the global environment. Since food and animal feeds are now routinely shipped long distances, this depletes the soil, just as Liebig and Marx contended in the nineteenth century, necessitating routine applications of commercial fertilizers on crop farms. At the same time this physical separation of where crops are grown and where humans or farm animals consume them creates massive disposal issues for the accumulation of nutrients in city sewage and in the manure that piles up around concentrations of factory farming operations. And the issue of breaks in the cycling of nutrients is only one of the many metabolic rifts that are now occurring. It is the change in the nature of the metabolism between a particular animal—humans—and the rest of the Earth System (including other species) that is at the heart of the ecological problems we face.

Despite the fact that our understanding of these ecological processes has developed enormously since Marx and Engels’s day, it is clear that in pinpointing the metabolic rift brought on by capitalist society they captured the essence of the contemporary ecological problem. As Engels put it in a summary of Marx’s argument in Capital, industrialized-capitalist agriculture is characterized by “the robbing of the soil: the acme of the capitalist mode of production is the undermining of the sources of all wealth: the soil and labourer.” For Marx and Engels this reflected the contradiction between town and country, and the need to prevent the worst distortions of the human metabolism with nature associated with urban development. As Engels wrote in The Housing Question:

The abolition of the antithesis between town and country is no more and no less utopian than the abolition of the antithesis between capitalists and wage-workers. From day to day it is becoming more and more a practical demand of both industrial and agricultural production. No one has demanded this more energetically than Liebig in his writings on the chemistry of agriculture, in which his first demand has always been that man shall give back to the land what he receives from it….

From Chapter 10:

The Theory of Unequal Ecological Exchange

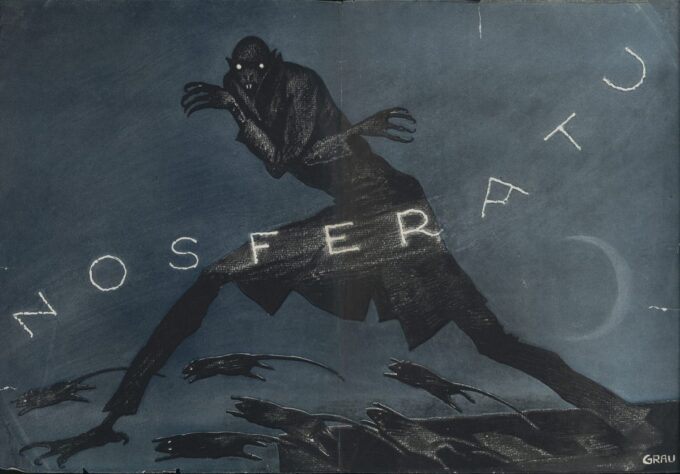

Just as unequal economic exchange theory postulated the exchange of more labor for less, unequal ecological exchange theory had as its basis the exchange of more ecological use value (or nature’s product) for less. Unequal ecological exchange was first raised as a major issue in the work of Liebig and Marx. From the 1840s to the 1860s, the great German chemist Justus von Liebig introduced a critique of industrial agriculture as practiced most fully in England, referring to this as a condition of “Raubbau” or the “Raubsystem,” a system of robbery or overexploitation of the land and agriculture at the behest of the new industrial capitalism emerging in the towns. In Liebig’s view, the elementary soil nutrients, nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium, were being removed from the soil and sent to the cities in the form of food and fiber, where they ended up contributing to pollution rather than being recirculated to the soil. The result was the systematic robbing of the soil of its nutrients. English agriculture, then, tried to compensate for this by importing bones from the catacombs and battlefields of Europe and guano from Peru. “Great Britain,” Liebig wrote,

deprives all countries of the conditions of their fertility. It has raked up the battlefields of Leipzig, Waterloo, and the Crimea; it has consumed the bones of many generations accumulated in the catacombs of Sicily; and now annually destroys the food for future generations of three millions and a half of people. Like a vampire it hangs on the breast of Europe, and even the world, sucking its lifeblood.

Marx developed Liebig’s approach into a more systematic ecological critique of capitalism by designating the robbery of the earth as “an irreparable rift in the interdependent process of social metabolism,” or metabolic rift. Such conditions were, for Marx, the material counterpart of the capitalist organization of labor and production. It constituted the alienation of the “metabolic interaction” between humanity and the earth, that is, of the “universal condition” of human existence.

The metabolic rift under capitalism was connected to unequal ecological exchange. England, as the leading capitalist country at the center of a world-system, Marx stated, was “the metropolis of landlordism and capitalism all over the world,” drawing on the resources of the globe, with nations in the periphery often reduced to mere raw material providers. “One part of the globe” is converted “into a chiefly agricultural [and raw material] field of production for supplying the other part, which remains a preeminently industrial field.” Thus a whole nation, such as Ireland, could be turned into “mere pasture land which provides the English market with meat and wool at the cheapest possible prices.” Indeed, Ireland was reduced by imperialist means to “merely an agricultural district of England which happens to be divided by a wide stretch of water from the country for which it provides corn, wool, cattle and industrial and military recruits.” The resulting “misuse” of “certain portions of the globe” in the periphery of the system is thus determined by the accumulation imperatives of the center. Marx illustrated the absolute robbery involved in the appropriation of the natural wealth of the one country by another by stating, “England has indirectly exported the soil of Ireland, without even allowing the cultivators the means for replacing the constituents of the exhausted soil.” Like Liebig, Marx pointed to the fact that England was forced to import guano in massive quantities from Peru (in a world-system of exploitation that also involved importing Chinese labor to dig the guano) in order to make up for the loss of nutrients in English fields.

Marx saw production as a flow of both material use values and exchange values or, simply, values. He used the term “metabolism” (Stoffwechsel) to refer to the material exchange (the exchange of matter-energy) that always accompanied monetary exchange of value….

Marxferatu: Teaching Marx with Vampires

Marxferatu: Teaching Marx with Vampires