Scientists have compared the calls, named 'antipredator pipes', to fear screams and panic calls

Author of the article:Devika Desai

Publishing date:Nov 10, 2021

Bees have developed their own version of a fire alarm to warn their hive of predatory murder hornets, a new study has found.

Once they’ve spotted a lurking giant or murder hornet, Asian honey worker bees will immediately string along series of panic calls — termed as “antipredator pipes” — which harsher and more irregular in their frequency.

Giant hornets or even Asian hornets which are closely related to the murder hornets recently discovered in North America are known to prey on bees and often send out scouting insects to search for hives to prey on. On finding one, the scout then returns to inform its nest, which then track the hive and often slaughter the entire colony.

“Antipredator pipes share acoustic traits with alarm shrieks, fear screams and panic calls of primates, birds and meerkats”, the study explains.

These pipes, scientists explain in their study published on Wednesday in the Royal Society Open Science journal, are actually vibroacoustic signals made by raising their abdomens, buzzing their wings and flying about “frantically.”

“These sophisticated defences require timely predator detection and swift activation of a defending workforce,” the authors wrote in the study

“Vibroacoustic signals likely play an important role in organizing these responses because they are transmitted quickly between senders and receivers within nests.”

Lead researcher Heather Mattila, professor of biological sciences at Wellesley College, Massachusetts and her team studied interactions between giant hornets and Asian honey bees in Vietnam for over seven years, by placing microphones in hives belonging to local beekeepers. The study collected almost 30,000 signals made by the bees over 1,300 minutes of monitoring.

“[Bees] are constantly communicating with each other, in both good times and in bad, but antipredator signal exchange is particularly important during dire moments when rallying workers for colony defense is imperative,” researchers wrote in their study.

In some cases, scientists observed that the signals prompted the worker bees at the hive’s entrance to go into defence mode, either attacking the scouting hornet by forming a ball around it to heat it to death or spreading animal dung on the hive to repel predators — the first document use of a tool by bees.

It’s unclear the signals do in fact indicate preparation for a specific type of defence, but as a whole, scientists suggest the the bee pipes are a “rallying call for collective defense.”

Scientists also found ‘striking differences’ in the way the bees responded to two types of predators – the giant hornet which attack in numbers and a smaller hornet species which hunts solitarily. The anti-predator pipes didn’t sound as much as for the latter, suggesting that the response may have been specifically developed for the larger, more dangerous predator.

“Colony soundscapes showcase the diversity of (the bees’) alarm signalling repertoire, including a novel antipredator pipe made by workers when (giant hornet) workers were present at nest entrances,” the study states.

“This research shows how amazingly complex signals produced by Asian hive bees can be,” behavioural ecologist Gard Otis was quoted by science website EurekaAlert! .

“We feel like we have only grazed the surface of understanding their communication. There’s a lot more to be learned.”

When murder hornets approach an Asian beehive, everyone can hear the screams.

JENNIFER OUELLETTE - 11/9/2021,

Wellesley College researchers have identified a sound that Asian honeybees use to warn the hive of a "murder hornet" attack.

Asian honeybees (Apis cerana) produce a unique alarm sound to alert hive members to an attack by giant "murder hornets," according to a new paper published in the journal Royal Society Open Science. For the first time, scientists at Wellesley College have documented these so-called "anti-predator pipes," which serve as clarion calls to the hive members to initiate defensive maneuvers. You can hear a sampling in the (rather disturbing) video, embedded above, of bees under a hornet attack.

“The [antipredator] pipes share traits in common with a lot of mammalian alarm signals, so as a mammal hearing them, there's something that is instantly recognizable as communicating danger,” said co-author Heather Mattila of Wellesley College, who said the alarm signals gave her chills when she first heard them. “It feels like a universal experience.”

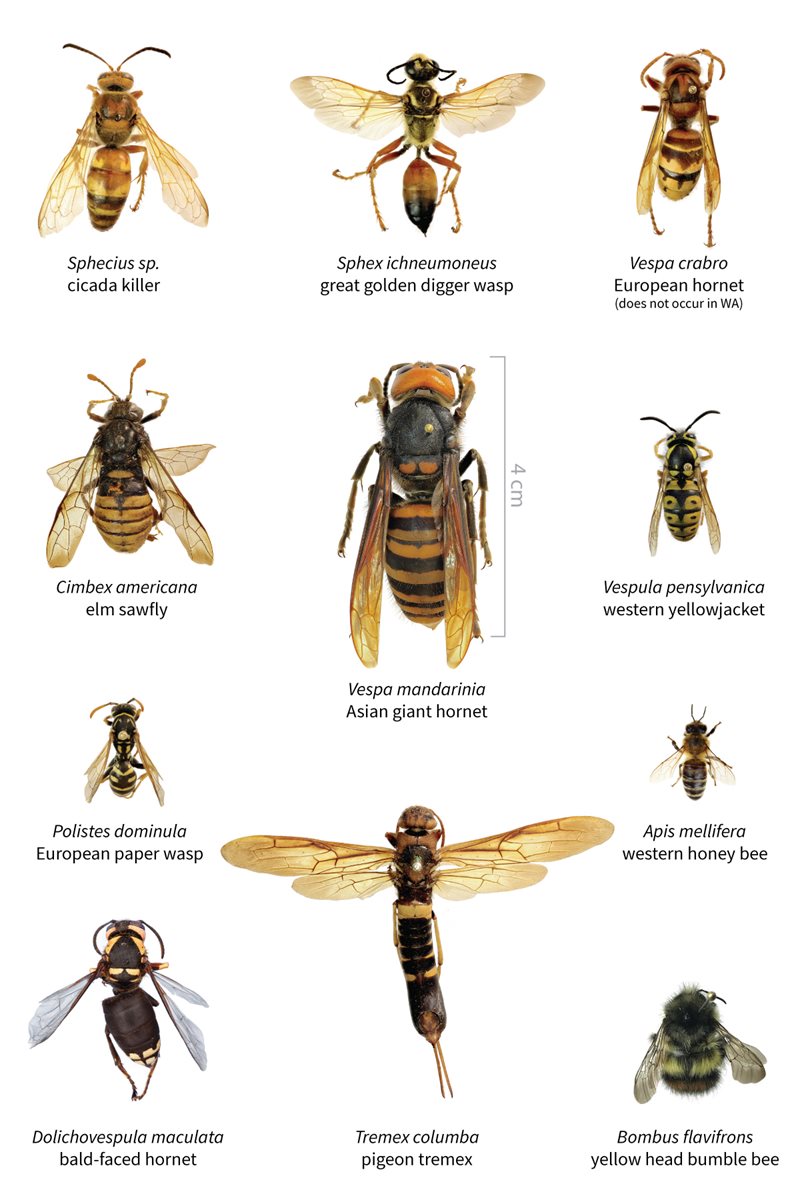

As I've written previously, so-called murder hornets rocketed to infamy after November 2019, when a beekeeper in Blaine, Washington, named Ted McFall, was horrified to discover thousands of tiny mutilated bodies littering the ground—an entire colony of his honeybees had been brutally decapitated. The culprit: the Asian giant hornet species Vespa mandarinia, native to Southeast Asia and parts of the Russian Far East. Somehow, these so-called "murder hornets" had found their way to the Pacific Northwest, where they now pose a dire ecological threat to North American honeybee populations.

FURTHER READING Attack of the Murder Hornets is a nature doc shot through horror/sci-fi lens

There are other species of Asian giant hornets, too. They are apex predators and sport enormous mandibles that they use to rip the heads off their prey and remove the tasty thoraxes (which include muscles that power the bee's wings for flying and movement). A single hornet can decapitate 20 bees in one minute, and just a handful can wipe out 30,000 bees in 90 minutes. The hornet has a venomous, extremely painful sting—and its stinger is long enough to puncture traditional beekeeping suits. And while Asian honeybees have evolved defenses against the murder hornet, North American honeybees have not, as the slaughter of McFall's colony clearly demonstrated.

Mattila has been studying honeybees for 25 years, fascinated by their organization and ability to communicate, and she turned her attention to Asian bees in 2013. "They have evolved in a much scarier predator landscape," she told Ars, pointing to the 22 known species of hornets worldwide for whom Asia is a particular hot zone. Many of these species rely on insects like honeybees to grow their colonies, so they are among the bees' most relentless predators. The deadliest of all are the giant hornets (aka, "murder hornets") because they coordinate in groups to attack beehives.

"As humans, I think there is something fundamentally attractive about understanding predator-prey interactions," said Mattila. "Humans are both predators and prey, depending on the situation, so we've evolved under analogous circumstances as the bees. We can recognize their plight in the face of giant hornets."

Last year, Mattila and her team documented the first example of tool use by honeybees in Vietnam. The researchers discovered that Asian bees forage for animal dung and use it to line the entrances to their hives—a practice dubbed "fecal spotting." It serves as a kind of chemical weapon to ward off giant hornets. Mattila and her team found that hornets were far less likely to land on or chew their way into hives with entrances lined with animal dung.

How Honeybees use animal poop as a chemical weapon to protect hives from giant “murder hornets."

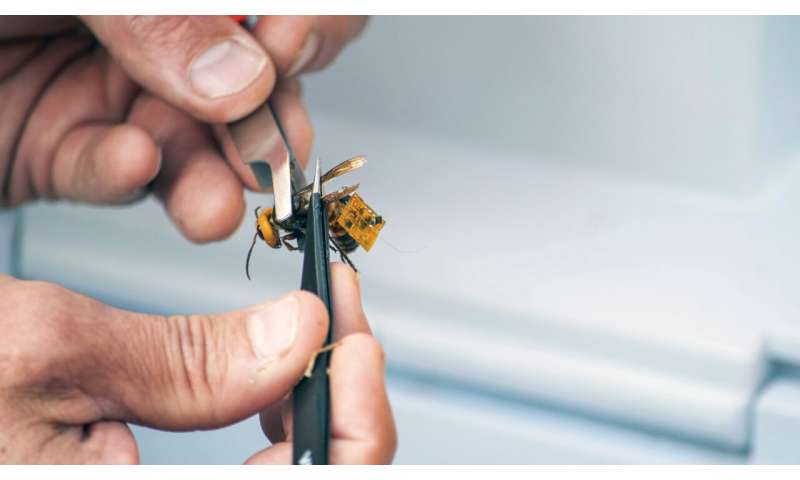

While Mattila and her team were in Vietnam for the dung study, they noticed that noise levels in the hives increased dramatically whenever the giant hornets approached. "We could hear the bees' sounds from several feet away," she said. "So we started popping microphones into colonies so that we could eavesdrop on them." They also took extensive video recordings of activity in the apiaries of local beekeepers.

Ultimately, they collected some 30,000 signals made by the bees over 1,300 minutes and then translated those sounds into spectrograms for analysis. Bees produce a surprisingly complex array of sounds, which they perceive either as air-particle movements they detect with their antennae or as vibrations they detect via special organs in their legs. So bee signals are "vibroacoustic" and are transmitted within colonies as both airborne sounds and vibrations.

There are hisses, for example, usually made by all the bees at once as they lower their bodies and move their wings in near-synchrony, Mattila said. They hiss constantly, but more so when hornets are present, and the exact purpose of the hissing is not yet fully understood.

"Hisses in other animals are often used to intimidate a predator, but that is not likely the case with bees, mostly because they hiss a lot without predators, too," said Mattila. "One idea that has been proposed (not by us) is that hissing helps to momentarily hush the colony because bees stand still for a beat after a hiss. It might help workers perceive other sounds in the nest if most bees stop moving for a second."

Enlarge / Giant murder hornets attack a honey bee hive in Vietnam.

Heather Mattila/Wellesley College

Piping signals accounted for the vast majority (about 95 percent) of the signals in the data set, but there was considerable variability, according to the authors. So-called "stop signals" were the most common (62 percent of the piping signals in the data set). These are produced when a worker vibrates its wings or thorax, typically in response to predator attacks, when fighting over a food source, and during swarming. "Stop signals are really short, [with a] relatively even frequency, and often delivered to other workers via a head butt," said Mattila. Asian honeybees produce more stop signals when hornets appear, and they will change the properties of those signals depending on the type of hornet that is attacking.

Although they are also produced by vibration of the wings or thorax, the newly discovered antipredator pipes are distinct from stop signals. They are harsher and more irregular, with abruptly shifting frequencies. Those colonies used in the study that were attacked by giant hornets were much noisier and frenetic, said Mattila, compared to the relative quiet and calm of the control colonies.

The bees under attack would run about frantically, often congregating at the hive entrance to form defensive "bee carpets." The mode of defense depends in part on the species of attacking hornets. Bees have also been known to form "bee balls" to kill attacking hornets collectively via overheating and suffocation. In fact, the authors wrote, "We observed workers attempt to bee ball a [hornet of the Vespa soror species] immediately after she killed a nest mate that was making antipredator pipes at the [hive] entrance." By contrast, the smaller Vespis velutina hornet attacks alone, targeting individual bees as it hovers in front of hives. The bees typically respond with coordinated "body shaking" as an intimidating visual display.

Enlarge / Biologist Heather Mattila of Wellesley College examines a group of honeybees.

Wellesley College

There was also a broad categorization of piping signals known as "long pipes" that accounted for 34 percent of all the piping signals in the data set. These lack the rapid and unpredictable frequency modulation of the antipredator pipes, according to the authors. "When frequency changed over the duration of these pipes, it did so in smooth sweeps," they wrote. Nor was the long pipe signaling affected by the type of hornet attack.

“[Bees] are constantly communicating with each other, in both good times and in bad, but antipredator signal exchange is particularly important during dire moments when rallying workers for colony defense is imperative,” the authors wrote. Furthermore, when they make those signals, the bees expose a pheromone-producing gland, suggesting they may employ multiple communication strategies to grab the attention of their nest mates. A future focus of Mattila's research will be investigating the role this gland might play in organizing the bees' response to hornet attacks.

The ongoing pandemic has limited field work for the time being, but Mattila says her team has been mailing giant hornets to their labs around the world and have even brought on some new collaborators. Currently, the researchers are re-analyzing the hornet attack videos from the perspective of the hornets rather than the bees. "We're trying to figure out how they disseminate pheromones to recruit their nest mates to a group attack," she said. "These hornet pheromones are key stimuli that bees would be paying attention to—in addition to the alarm signals they produce for each other—to determine what kind of hornet is attacking them."

DOI: Royal Society Open Science, 2021. 10.1098/rsos.211215 (About DOIs).