Beverley D'Silva

BBC

From outrageous costumes to trick or treat: the unexpected ancient roots of Halloween's most popular – and most esoteric – traditions.

With its goblins, goosebumps and rituals – from bobbing for apples to dressing up as vampires and ghosts – Halloween is one of the world's biggest holidays. It's celebrated across the world, from Poland to the Philippines, and nowhere as extravagantly as in the US, where in 2023 $12.2 billion (£9.4 billion) was spent on sweets, costumes and decorations. The West Hollywood Halloween Costume Carnival in the US is one of the biggest street parties of its kind; Hollywood parties such as George Clooney's tequila brand's bash make a big social splash; and at model Heidi Klum's party she is renowned for her bizarre disguises, such as her iconic giant squirming worm outfit.

Heidi Klum wore a worm costume for Halloween 2022 in NYC – scary disguises were originally intended to ward off evil spirits (Credit: Getty Images)

With US stars turning out again for the biggest dressing-up show after the Oscars' red carpet, it's no surprise Halloween is often viewed as a modern US invention. In fact, it dates back more than 2,000 years, to Ireland and an ancient Celtic fire festival called Samhain. The exact origins of Samhain predate written records but according to the Horniman Museum: "There are Neolithic tombs in Ireland that are aligned with the Sun on the mornings of Samhain and Imbolc [in February], suggesting these dates have been important for thousands of years".

Celebrated usually from 31 October to 1 November, the religious rituals of Samhain (pronounced "sow-win", meaning summer's end), focused on fire, as winter approached. Anthropologist and pagan Lyn Baylis tells the BBC: "Fire rituals to bring light into the darkness were vital to Samhain, which was the second most important fire festival in the Pagan Celtic world, the first being Beltane, on 1 May." Samhain and Beltane are part of the Wheel of the Year, an annual cycle of eight seasonal festivals observed in Paganism (a "polytheistic or pantheistic nature-worshipping religion", says the Pagan Federation).

The ancient Celtic festival of Samhain is still celebrated in some places, including Glastonbury Tor, pictured in 2017 (Credit: Getty Images)

Samhain was the pivotal point of the Celtic Pagan new year, a time of rebirth – and death. "Pagans had three harvests: Lammas, harvest of the corn, on 1 August; the one of fruit and vegetables at autumn equinox, 21 September; and Halloween, the third," says Baylis. At this time animals that couldn't survive winter were culled, to ensure the other animals' survival. "So there was a lot of death around that time, and people knew there would be deaths in their villages during the harsh winter months." Other countries, notably Mexico, celebrate The Day of the Dead around this time to honour the deceased.

Costumes and ugly masks were worn to scare away malevolent spirits believed to have been set free from the realm of the dead

At Samhain, Celtic Pagans in Ireland would put out their home fires and light one giant bonfire in the village, which they would dance around and act out stories of death, regeneration and survival. As the whole village joined in to dance, animals and crops were burned as sacrifices to Celtic deities, to thank them for the previous year's harvest and encourage their goodwill for the next.

It was believed that at this time the veil between this world and the spirit world was at its thinnest – allowing the spirits of the dead to pass through and mingle with the living. The sacred energy of the rituals, it was believed, allowed the living and the dead to communicate, and gave Druid priests and Celtic shamans heightened perception.

And this is where the dress-up factor came in – costumes and ugly masks were worn to scare away malevolent spirits believed to have been set free from the realm of the dead. This was also known as "mumming" or "guising".

Those early Samhain dressing-up rituals began to change when Pope Gregory 1 (590-604) arrived in Britain from Rome to convert Pagan Anglo-Saxons to Christianity. The Gregorian mission decreed that Samhain festivities must incorporate Christian saints "to ward off the sprites and evil creatures of the night", says Baylis. All Souls Day, 1 November, was created by the Church, "so people could still call on their dead to aid them"; also known as All Hallows, 31 October later became All Hallows' Eve, later known as Halloween.

"There is a long tradition of costuming of sorts that goes back to Hallow Mass when people prayed for the dead," explains Nicholas Rogers, a history professor at York University in Canada. "But they also prayed for fertile marriages." Centuries later boy choristers in the churches dressed up as virgins, he says. "So there was a certain degree of cross-dressing in the ceremony of All Hallow's Eve."

New York City Halloween parade participants in the early 1980s (Credit: Getty Images)

The Victorians loved a ghost story, and adopted non-religious Halloween costumes for adults. Later, after World War Two, the day centred on children dressing up, a ritual still alive today at trick-or-treating time. Since the 1970s, adults dressing up for Halloween has become widespread again, not just in creepy and ugly costumes, but also hyper-sexualised ones. According to Time, these risqué outfits emerged because of the "transgressive" mood of the occasion, when "you can get away with it without it being seen as particularly offensive". In the classic teen film Mean Girls, it's jokingly said that "in girl world" Halloween is the "one night a year when girls can dress like a total slut and no other girls can say anything about it". It's not just in "girl world" that Halloween has a disinhibiting effect – it is a hugely popular holiday in the LGBTQ+ community, and is often referred to as "Gay Christmas". In New York, the city famously comes alive every year with a Halloween parade featuring participants in elaborate and outlandish costumes.

Playing with fire

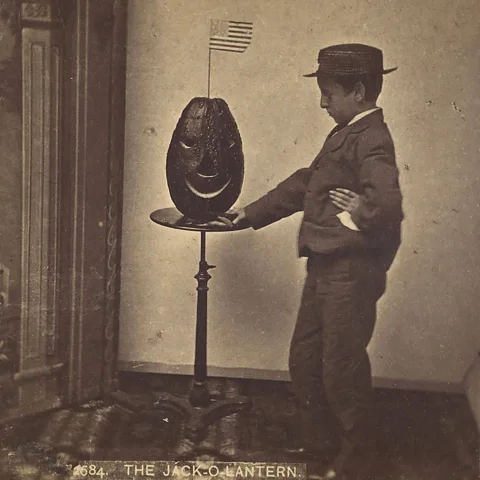

Echoes of Samhain also live on today in fire practices. Carving lanterns from root vegetables was one tradition, although turnips, not pumpkins, were first used. The practice is said to have grown from a Celtic myth, about a man named Jack who made a pact with the devil, but who was so deceitful that he was banned from heaven and hell – and condemned to roam the darkness, with only a burning coal in a carved-out turnip to light the way.

The ritual of carving lanterns out of pumpkins came from the myth of a man called Jack who made a pact with the devil (Credit: Getty Images)

In Ireland, people made lanterns, placing turnips with carved faces in their window to ward off an apparition called "Jack of the Lantern" or Jack-o'-Lantern. In the 19th Century, Irish immigrants took the custom with them to the US. In the small Somerset village of Hinton St George in the UK, turnips or mangolds are still used, and elaborately carved "punkies" are paraded on "punkie night", always the last Thursday of October. In the UK town of Ottery St Mary there is still an annual "flaming tar barrels" ritual – a custom once practised widely across Britain at the time of Samhain, where flaming barrels were carried through the streets to chase away evil spirits.

Soulers went door to door singing and saying prayers for souls in exchange for ale, cakes and apples

Leaving food and sweetly spiced "soul cakes" or "soulmass" cakes on the doorstep was said to ward off bad spirits. Households deemed less generous with their offerings would receive a "trick" played on them by bad spirits. This has translated into modern-day trick or treating. Whether soul cakes came from the ancient Celts or the Church is open to argument, but the idea was that, as they were eaten, prayers and blessings were said for the dearly departed. From Medieval times, "souling" was a Christian tradition in English towns at Halloween and Christmas; and soulers (mainly children and the poor) went door to door singing and saying prayers for souls in exchange for ale, cakes and apples.

Advertisement

More like this:

• Britain's most chaotic rituals

• The historic roots of goth

• Is County Meath the birthplace of Halloween

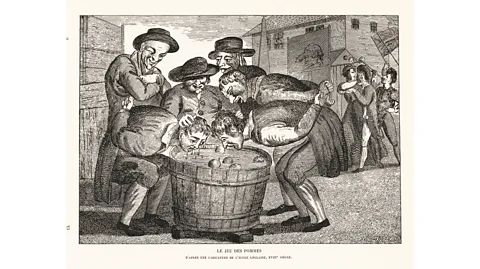

Apple bobbing – dipping your face into water to bite an apple – dates back to the 14th Century, according to historian Lisa Morton: "An illuminated manuscript, The Luttrell Psalter, depicted it in a drawing." Others date the custom back further, to the Romans' conquest of Britain (from AD43) and the apple trees that they imported. Pomona was the Roman goddess of fruitful abundance and fertility, and hence, it is argued, apple bobbing's ties to love and romance. In one version, the bobber (usually female) tries to bite into an apple bearing her suitor's name; if she bites it on the first go, she is destined for love; two gos means her romance will start but falter; three means it will never get started.

It is thought that apple bobbing originated in the 14th Century – or possibly even further back (Credit: Getty Images)

British rituals, at the heart of Halloween traditions, are the subject of Ben Edge's book, Folklore Rising, illustrated with his mystical paintings. Edge says that he has observed a "resurgence of people becoming interested in ritual and folklore… I call it a folk renaissance, and I see it as a genuine movement led by younger people".

He cites such artists as Shovel Dance Collective, "non-binary, cross-dressing and singing traditional working men's songs of the land". There is also Weird Walk, a project "exploring the ancient paths, sacred sites and folklore of the British Isles… through walking, storytelling and mythologising." If interest in folk rituals is on the rise, so too are the numbers turning to such traditions as Paganism and Druidry, both adhering to the Wheel of the Year, and Samhain, "dedicated to remembering those who have passed on, connecting with the ancestors, and preparing ourselves spiritually and psychologically for the long nights of winter ahead".

The Flaming Tar Barrels of Ottery St Mary (2020) is featured in artist Ben Edge's book about ancient traditions, Folklore Rising (Credit: Ben Edge)

Philip Carr-Gomm, a psychologist, author and practising druid, says that he has witnessed a "steady growth" in interest around Druidry over the past few decades. "We now have 30,000 members, across six languages," he tells the BBC.

The need for ritual, connectedness and community is at the heart of many Halloween traditions, says Baylis: "One of the most important aspects of Halloween for us is remembering loved ones. We light a candle, possibly say the name of the person or put a picture of them on an altar. It's a sacred time and ceremony, but you don't have to be a Pagan to be involved. The important thing is that it comes from a place of protection and love."