Smithfield is pushing a massive greenwashing campaign to dupe consumers into thinking its products are environmentally friendly.

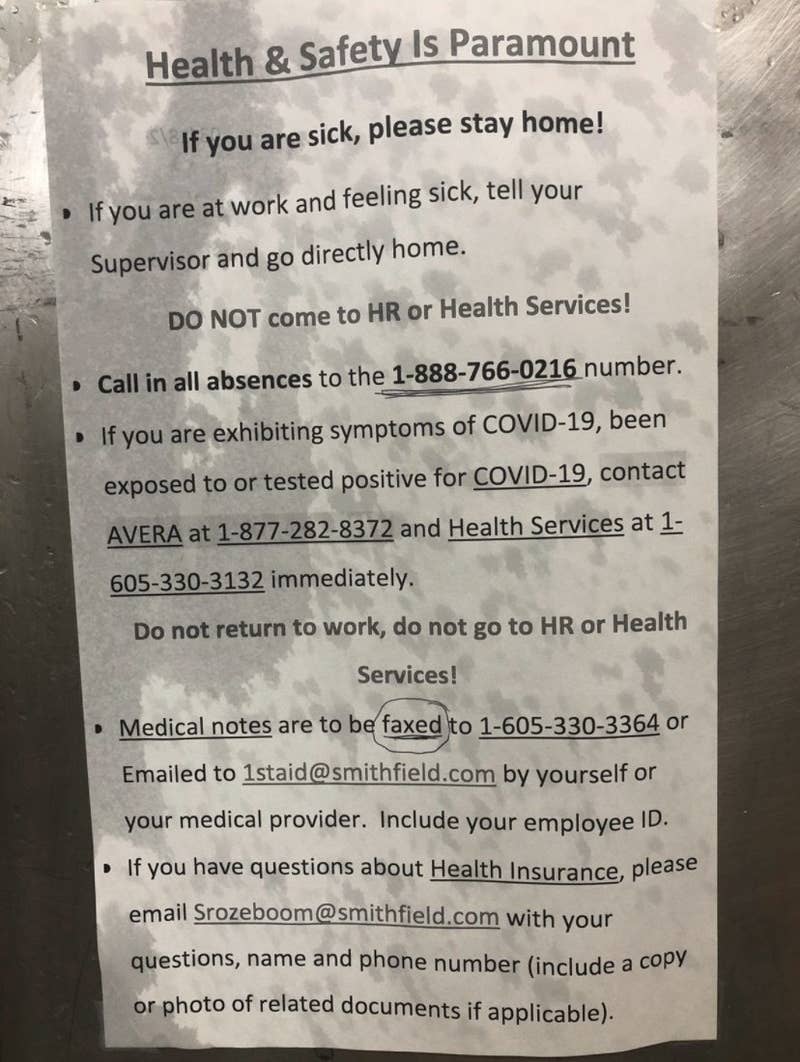

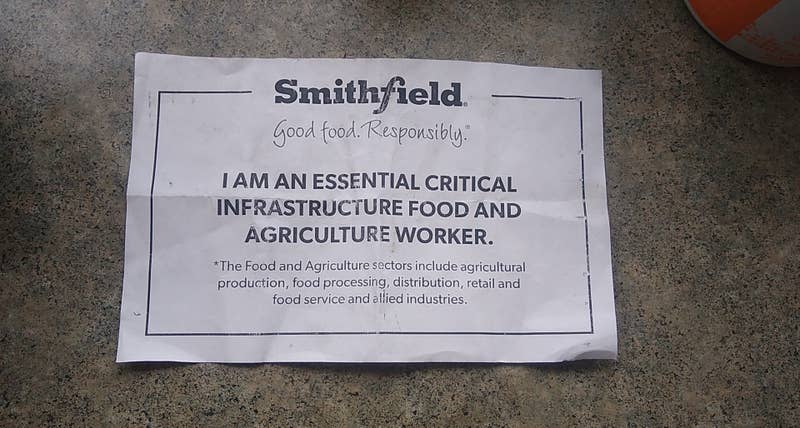

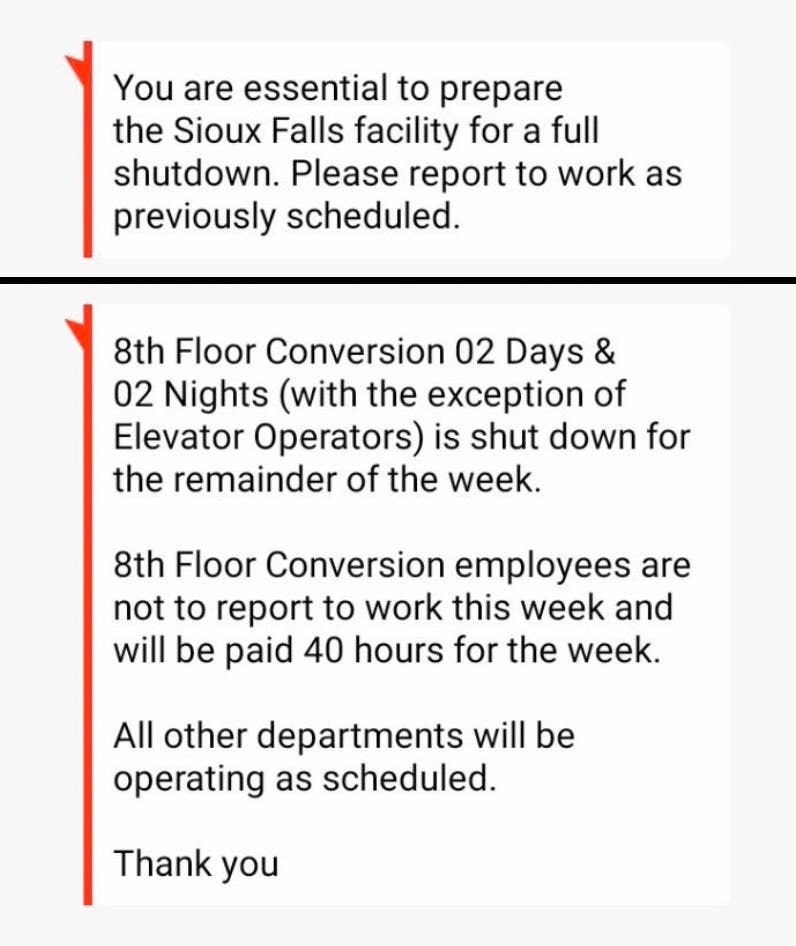

A sign outside the Smithfield Foods pork processing plant in South Dakota, one of the countrys largest known Coronavirus clusters, is seen on April 21, 2020 in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. - Smithfield Foods pork plant in South Dakota is closed indefinitely in the wake of its coronavirus outbreak.(Photo by KEREM YUCEL/AFP via Getty Images)

We’ve all probably seen them, advertisements from corporate polluters that sound like they could have been written by an environmental protection group. This tactic, called greenwashing, has become all the rage with some of the biggest polluters to cover up their poisoning of the environment and harm to communities. And Smithfield Foods is a prime example, pushing an aggressive greenwashing campaign so that consumers will overlook that it is one of the biggest industrial polluters in the United States.

What Smithfield is really doing is doubling down on its legacy of extreme pollution, because its factory farm biogas scheme fundamentally depends on the worst parts of how it has chosen to produce its pork products on the cheap.

Instead of cleaning up its act by actually making its products without destroying the environment and health of those unlucky enough to live near its plants and the factory farms that raise its pigs, Smithfield is investing in slick tag lines and doubling down on its devastating factory farm model. Day in and day out Smithfield gets rich while spewing dangerous pollutants into our water, air, and soil. And now Smithfield is partnering with fossil fuel corporations to push factory farm “biogas” schemes to monetize its deliberate mismanagement of the nearly unfathomable amounts of waste it produces year after year. Factory farm biogas is a false solution that expands and entrenches the worst aspects of mega-factory farms and the dirty natural gas industry. But throughout Smithfield’s marketing — on its websites, social media accounts, and elsewhere—it tells consumers that its pork products are environmentally friendly and that it is a sustainability leader and climate champion. It’s grade-A greenwashing at its finest.

Not only is this deception bad for consumers and family farmers, it’s illegal. That’s why we’re calling on federal regulators to hold Smithfield accountable and put a stop to its false and misleading advertising.

Smithfield Is One of the Biggest Industrial Polluters, Making a Mockery of Its Sustainability Claims

Smithfield is one of the most harmful industrial polluters in the United States. It consistently puts profits over people and the environment, with factory farms and processing facilities throughout the country that rack up dozens of environmental violations every year. This is why Smithfield has been hit with tens of millions of dollars in damages as impacted communities have successfully taken the mega-polluter to court for causing conditions that make their homes nearly unlivable. The federal judges did not mince their words, recognizing that “interlocking dysfunctions” are characteristic of how Smithfield produces its products, and that the company willfully and wantonly harmed its neighbors to maximize profits.

Smithfield’s Claims About Factory Farm Biogas Are Quintessential Corporate Greenwashing

Smithfield’s latest scheme to hide its harm to public health and the climate is its promotion of anaerobic digesters to produce so-called “biogas.” These digesters are tanks or lagoons that create an oxygen-free environment where microbes eat part of Smithfield’s manure and emit a mixture of gases, mostly methane and carbon dioxide, that the digester captures. This factory farm biogas can then be refined and burned just like fossil natural gas. Far from showing a “longstanding commitment to sustainability,” as Smithfield claims, building new factory farms and entrenching its irresponsible waste mismanagement to extract biogas only perpetuates the myriad harms caused by its factory farm production model. In fact, Smithfield’s digesters can make its waste even more harmful to waterways than what it started with.

What Smithfield is really doing is doubling down on its legacy of extreme pollution, because its factory farm biogas scheme fundamentally depends on the worst parts of how it has chosen to produce its pork products on the cheap. Smithfield promotes digesters as reducing its methane emissions and producing “renewable” energy, but fails to mention that this methane is the direct result of Smithfield’s preferred waste management practice, where it liquifies enormous quantities of manure and stores it cheaply in rudimentary “lagoons” (pictured in the image above during a flood). In contrast, when animal manure breaks down naturally, on a pasture for example, it does not generate methane. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas that is 90 times more harmful to the climate than carbon dioxide over a 20-year time period. Simply put, Smithfield misleadingly tells consumers its pork is environmentally friendly and that it is a leader in sustainability because it is slapping a bandaid over the climate destroying pollution that it deliberately created in the first place. But we aren’t letting this deception go unanswered.

Taking the Smithfield Greenwashing Case to the Federal Trade Commission

Food & Water Watch and a coalition of environmental and sustainable, family farming groups* have filed a complaint with the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) calling for enforcement of federal law against Smithfield’s false and misleading marketing. Under the FTC Act, companies are prohibited from promoting their products in any way that is likely to mislead reasonable consumers. As our complaint makes clear, Smithfield’s sustainability marketing tells consumers that its pork products have environmental attributes that are in stark contrast to the reality of how Smithfield does business, duping them into buying its products.

This unfair and illegal practice not only harms consumers, but also harms truly sustainable family farmers who invest the time, effort, and money into producing products that actually match what conscientious consumers expect. By illegally marketing its products, Smithfield makes it nearly impossible for these honest producers to compete in the marketplace, and for consumers to tell the difference.

Smithfield reportedly brought in more than $11 billion in revenue in 2020, so it can afford to clean up its act and transition away from the factory farm model that takes such a tremendous toll on the environment and local communities. But instead, it has opted for false solutions like factory farm biogas so it can wring more money out of its dangerous and polluting production facilities. Smithfield’s products are not “sustainable” or “environmentally friendly,” and the FTC must act to hold this mega-polluter accountable for lying to the public and its customers.

The closed Smithfield Foods pork plant is seen as the spread of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) continues, in Sioux Falls, S.D., on April 16, 2020.Shannon Stapleton / REUTERS

The closed Smithfield Foods pork plant is seen as the spread of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) continues, in Sioux Falls, S.D., on April 16, 2020.Shannon Stapleton / REUTERS