By Stephanie Pappas 3 days ago

Squid was embedded with sperm from a single male.

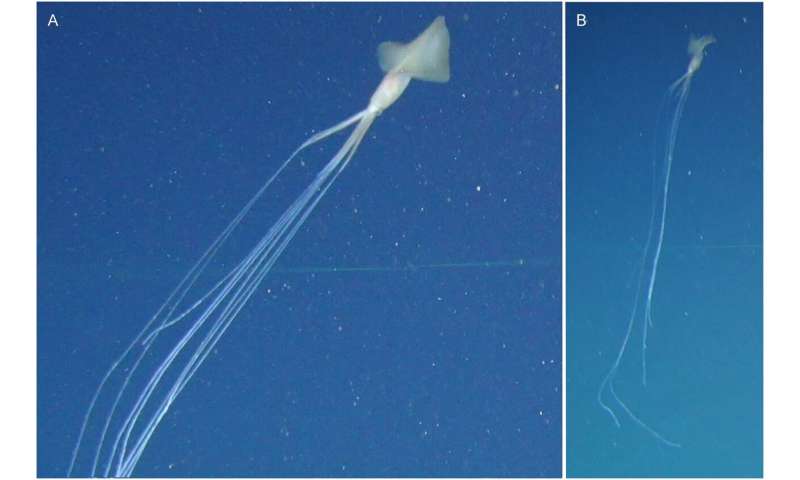

A female giant squid caught in a net off Kyoto had dozens of sperm packets from a single male embedded in her muscles. (Image credit: Miyazu Energy Aquarium)

A female of the world's largest squid — sometimes called the "kraken" after the mythological sea monster — that was caught off the coast of Japan apparently had just one amorous encounter in her lifetime.

The female had sperm packets from just one male giant squid embedded in her body, which surprised researchers. Because giant squid are solitary creatures that probably run across potential mates only occasionally, scientists expected that females would opportunistically collect and store sperm from multiple males over time.

"We were almost confident that they are promiscuous," said Noritaka Hirohashi, a biologist at Shimane University in Japan. "We just wanted to know how many males are involved in copulation. So this is totally unexpected."

Related: Release the kraken! Giant squid photos

Mysterious mating

Hirohashi and his colleagues study reproduction and sperm biology in several squid species, but the most mysterious of all is Architeuthis dux, the giant squid. Rarely seen alive, the giant squid has a life cycle shrouded in deep ocean mystery. Video of living giant squid in their natural habitats has been captured only twice. The only thing researchers know about these mysterious creatures' mating habits is that female giant squid are sometimes found with large sperm packets known as spermatangia embedded in their muscles. Researchers writing in a 1997 paper in the journal Nature posited that male giant squid probably use their "muscular elongate penis" to inject the sperm packets into the females.

How sperm meets egg from there isn't entirely clear. It's possible that the female releases chemical cues that activate the sperm when she's ready to spawn, or perhaps she releases her eggs in such a way that they trail along the sperm packets as they leave her body. Squid females do have organs near the mouth called seminal receptacles, where some species storm sperm, and it's possible that in those species, the embedded sperm can travel over the skin to these receptacles.

Knowing that witnessing two giant squid mating is highly unlikely, Hirohashi and his team developed a window into the process, using genetics. Examining squid specimens from fisheries and museum archives, they pinpointed some segments of the giant squid genome that would distinguish one set of squid DNA from another. Think of it like a squid paternity test: Any sperm packets found on a female can be tested to see if they came from multiple males and, if so, how many.

The researchers are always on the lookout for sperm-spangled females. They send out flyers to local museums, fisheries and aquariums, asking them to alert the research lab if a giant squid specimen turns up. In February 2020, they got good news.

"In this case, we found [a] Yahoo News [article] telling that the giant squid was caught," Hirohashi wrote in an email to Live Science.

Saving sperm

The spermatangia, or sperm packets, embedded in the upper layer of muscle on the female giant squid. No one knows how the sperm get to the eggs to fertilize them. (Image credit: Miyazu Energy Aquarium)

The specimen was a female, with a mantle, or main body, 5.25 feet (1.6 meters) long. It was missing a pair of tentacles and one eye but still weighed 257 pounds (116.6 kilograms). The squid had been caught in a fisher's net in Kyoto and was displayed at the Miyazu Energy Aquarium before being dissected.

When Hirohashi's team examined the body, they found that the squid was just reaching maturity and that it had squiggly spermatangia 3.9 inches (10 centimeters) long embedded in five separate locations: three places on the squid's mantle, one by an arm and one on the head. Each location hosted at least 10 spermatangia. Some were near gashes that may have been caused by a mating male's beak.

Genetic analysis of the spermatangia revealed that each and every one came from the same male. This was shocking to the research team; giant squid are often found bearing sperm packets, in a way that suggests that males aren't particularly picky. Spermatangia have been found on immature females, perhaps as a way for males to make their sperm available after the female matures, and even on males, perhaps because males are willing to try anything (or perhaps because they sometimes accidentally self-fertilize). All of the evidence pointed to a species that would mate first and ask questions later.

RELATED CONTENT

—Animal sex: 7 tales of naughty acts from the wild

—Gallery: Vampire squid from hell

—Under the sea: A squid album

The specimen, of course, is just one female, so more research is needed to see if monogamy is the norm among giant squid females. It's possible that this female had simply only encountered one male before she was entangled in the net that ended her life, the researchers wrote in the September issue of the journal Deep Sea Research Part 1. Or perhaps it is typical for females to mate with just one male. The gashes might be part of the males' strategy for ensuring other males don't move in, perhaps by limiting a female's life span after mating so that she doesn't have time to collect more sperm. Or, the researchers speculated, the aggression and injuries could spur the females to mature and spawn so that the sperm is speedily fertilized.

The next step is to study the spermatangia of more specimens, Hirohashi said. And researchers need to figure out how the stored sperm reaches the eggs, which are not deposited particularly close to the spermatangia. Researchers also need to figure out basically everything else about this elusive creature, including its life span, migration and habitats, he added.

"Kids ask these questions at the aquarium, so we must answer," Hirohashi said.

Originally published on Live Science