Ian Duncan, Jul 12 2022

NAM Y. HUH/AP

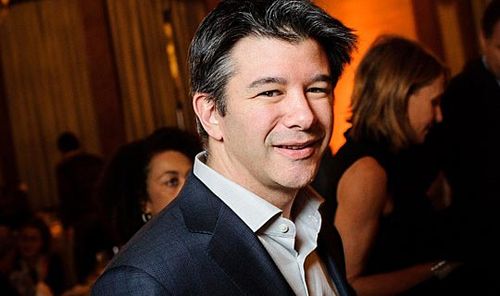

When Uber chief executive Travis Kalanick touched down in Moscow in June 2016, Uber was on the march in Russia.

The company had worked hard to forge ties in a nation notoriously tricky for Western businesses and had leaned on all the questionable, grow-at-all-costs tactics that had become its hallmark around the globe.

It cultivated oligarchs and government officials at a time when the country faced growing international condemnation for seizing Crimea from Ukraine and stoking war in that country's east. It sold a US$200 million (NZ$327m) stake to a pair of oligarchs in a quest to get close to Russian President Vladimir Putin, despite the authoritarian drift of Putin's government, then, according to previously unpublicised emails among company executives, offered a US$50 million deal sweetener that it didn't publicise. It agreed, emails show, to hire a lobbyist for as much as US$650,000 in an arrangement so concerning to Uber's lawyers that they insisted the lobbyist submit to training in US anti-bribery law.

Uber's approach appeared to be working, and on the second night of Kalanick's trip, tech entrepreneurs and government officials assembled around a vast table to dine with the Uber executive at the Moscow City Golf Club.

READ MORE:

* Uber Files whistleblower exposes company's inner workings, and the 'lie' being sold to people

* Uber leveraged violent attacks against its drivers to pressure politicians

* Former Uber CEO Travis Kalanick severs ties with ride-hailing giant

* Uber promises to make things right in London after 'constructive' licence meeting

Six kilometres from the Kremlin, the 9-hole club stood atop a former city dump and wasn't as fancy as those in the suburbs, but it still offered a kind of stuffy luxury. According to a table plan obtained by The Washington Post, Kalanick was to sit across from one of Putin's ministers and the head of Sberbank, Russia's biggest bank.

Kalanick left the following morning, seemingly happy with his time in Moscow. His team was pleased, too.

"Russia trips seems to have been a success," Rachel Whetstone, then the company's communications director, wrote to Mark MacGann, a former Uber public policy executive who by then had become an adviser to the board and had joined the trip to chaperone Kalanick.

"Was a great 36-hour immersion," MacGann replied. "Media very strong”.

Uber viewed Russia as among the company's most important foreign markets, according to a memo that is part of the Uber Files, a trove of more than 124,000 documents that MacGann provided to the Guardian. It shared the trove with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, a nonprofit newsroom in Washington, DC, that helped lead the project, and dozens of other news organisations, including The Washington Post. The documents provide a detailed look at the aggressive strategies Uber adopted to grow in Europe and other international markets. MacGann was the company's' head of public policy from 2014 to 2016.

That memo shows that Uber believed Russia's dozen "millionniki" - cities home to at least a million people - presented a ripe opportunity. But like the golf club's, Uber's foundations in Russia were questionable. A little over a year later, Uber would essentially pull out of the country.

The retreat was evidence that even with piles of investor cash and a willingness to embrace the Russian elite at a time of growing authoritarianism, Uber's growth had limits. In nations such as Russia and China, which Uber also exited, the pathways to power were obscure to outsiders, and homegrown competitors could dominate.

The files do not contain evidence that Uber violated sanctions or broke the law as it tried to grow in Russia. But today, following Russia's invasion of Ukraine, almost everyone with whom Uber allied then is under sanction for their alleged ties to Putin by US or European authorities.

Devon Spurgeon, a spokesperson for Kalanick, said he had only limited involvement in Uber's expansion in Russia and was not aware of anyone acting on Uber's behalf in the country in a way that violated American or Russian laws.

CHRIS J RATCLIFFE/GETTY IMAGES

The company had worked hard to forge ties in a nation notoriously tricky for Western businesses.

"Kalanick's role was limited to a trip to Russia that included a few meetings arranged by Uber's policy and business development teams," Spurgeon said. She added that Kalanick "was asked for his involvement" after Uber's "robust" legal, policy and business development teams had "vetted and approved the strategy and operations plans."

"Kalanick acted at all times lawfully and with the clear approval and authorization of Uber's legal team," Spurgeon said. "Kalanick is not aware of anyone acting on Uber's behalf in Russia who engaged in any conduct that would have violated either Russian or US law."

Jill Hazelbaker, a spokeswoman for Uber, said nobody currently at the company was involved in developing its strategy in Russia and that today it discloses its anti-corruption policies.

"Current Uber management thinks Putin is reprehensible and disavows any previous association with him or those close to him," Hazelbaker wrote.

But in 2016, Russia's future remained unclear, and Uber's leadership had reason to think its investments would pay off.

The files show that Sberbank's chief executive, Herman Gref, introduced Uber officials to the mayor of Moscow, and Uber credited the bank's help in securing a deal with city authorities that avoided a demand that all Uber drivers have yellow cars. They also show that in February 2016, Uber accepted US$200 million from LetterOne, the investment firm of Mikhail Fridman and Petr Aven, oligarchs who made their fortunes after the collapse of the Soviet Union, and struck a secret deal worth an additional US$50 million to encourage them to aid its success in Russia.

With the help of a lobbyist Fridman and Aven's firm recommended, company emails and memos show, Uber was working to have a federal law on taxis written to stop regional governments from being able to limit Uber's growth.

Jessica Tillipman, an assistant dean at George Washington University Law School, said that pursuing that kind of lobbying strategy in Russia, where the risk of corruption is high, would have been risky under American anti-bribery laws.

"It's kind of a blazing red flag," she said. "There are many companies that would opt to walk away from something like this”.

By year's end, Uber expected to be in 18 cities in Russia, according to a company memo.

But there were signs that not all was well. As an American company with global ambitions, Uber was increasingly out of step with how Russia was evolving in the mid-2010s.

The company's core customers were westward-looking members of the middle class - whom Uber portrayed as wanting to use the same app Parisians used, even if they could no longer afford to travel to France, according to a company memo - and its political allies were economic reformers with ties to the United States and Europe. But the rising force in Russia was Putin, who was consolidating control over the country and curbing the independence of tech companies in particular.

Uber had other weaknesses, too. Consultants hired by Uber had concluded that Fridman and Aven's political influence was not what it had been thought to be, according to a report they provided to the company. Company executives would soon come to believe their handpicked lobbyist hadn't done much to justify his tens of thousands of dollars in monthly fees. And while Uber hadn't faced the kind of entrenched opposition from the taxi industry that it had battled elsewhere in Europe, it did have to contend with a large, homegrown rival in the form of Russia's answer to Google, Yandex.

Despite MacGann's upbeat appraisal of the Moscow trip for Whetstone, he shared a different view of Kalanick's performance with David Plouffe, a former adviser to US President Barack Obama who, as an Uber executive, had helped lay the groundwork for the company in Russia.

"Neither his head nor his heart are in it," MacGann wrote in an email. "He's exhausted”.

AMY RIDOUT/STUFF

Uber tried to get a foothold in Russia.

Uber had entered Russia in 2013, initially facing little opposition. But after it launched the low-cost UberX service, the authorities began to take notice. A backbench member of the Duma, the lower chamber of Russia's parliament, wrote to Putin and Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev in September 2014 calling for the company to be banned. There was little threat of that, Uber's leaders concluded, but they began looking for oligarchs and other influential figures who could serve as allies.

Emil Michael, then Uber's chief business officer, wrote to MacGann that month wondering whether Roman Abramovich, then the owner of the Chelsea soccer club in England, might be a good choice: "I think we want someone aligned with Putin and I don't know the politics in Russia super well."

In early 2015, Uber's leaders in Russia and Europe began sizing up a shortlist of the country's richest men, emails show. Experts on Russian politics say it's not clear how much sway many oligarchs - billionaires who in some cases made their fortunes by snapping up government assets after the fall of the Soviet Union - held as Putin tightened his grip.

But Uber's leaders and advisers saw them as the key to success, replicating an approach the company had used in other countries that involved lining up strategic partners who brought both money and political influence.

In Russia, though, it was a potentially risky path.

MacGann sent a note listing five possible names, and Dmitri Izmailov, Uber's manager in Russia, circulated a brief memo in January summarising their wealth, business interests, political ties and accusations of wrongdoing they had faced: "It's a colourful group of people."

Izmailov declined to comment.

Among the candidates was Alisher Usmanov, a metals magnate, who was convicted of economic offences in the 1980s during the Soviet era. His spokesman said the charges were politically motivated and later overturned. Hazelbaker said that at the time he was being considered, Uber executives were aware he had been accused of corruption.

Three days later, MacGann wrote to Michael that he had spoken with an investor who worked for Usmanov.

Michael urged caution: "We got to be clean with Russia investors, but at the same time not insult them so let's be careful what we say to any Russian investors."

Asked recently about the exchange, a spokesman for Michael said Uber's foreign investors were approved and vetted by the company's policy and public relations team, and its legal and compliance team.

"Uber operated in Russia along with most other large US-based global businesses," the spokesman said. "Uber never courted any individuals who were subject to US sanctions in any way and abided by best practices for all US businesses operating in the country."

Usmanov would invest US$20 million in Uber before the end of 2015, according to Uber memos. The company's team in Russia planned to put his influence to use, according to a strategy document from that fall, but there's no record in the files of him aiding Uber. When Uber was asked by Fortune about the investment in early 2016, Michael wrote to MacGann and another Uber executive, "We DO NOT want to confirm this at all."

Grigory Levchenko, a spokesman for Usmanov's company, USM, said Usmanov had never been involved in politics. "USM and Uber were negotiating a purely financial investment, and USM's involvement was limited to this," Levchenko said, adding that USM made a profit on its investment in Uber.

By March 2015, Abramovich had decided not to invest but continued to advise Uber as it sought other partners in Russia. The company's leaders had added Sberbank to its target list. The bank traces its history back to the time of the czars, and under Gref's leadership it had been overhauled and modernized.

MacGann said he could make the introduction to Gref, and in July 2015, he and Plouffe made a trip to Moscow to begin the long courtship that culminated in the golf club dinner.

Plouffe did not respond to questions about his activities for Uber involving Russia. Gref and Sberbank did not respond to questions about their dealings with Uber.

ANDY JACKSON/STUFF

Russia was seen as a key emerging market for the company.

As the Uber team began to establish relationships in Russia, the challenge the Moscow authorities posed to Uber's growth was becoming clear.

A top official in the Moscow government had called for national regulation of ride-hailing companies and demanded an investigation into Uber. On August 24, 2015, a local prosecutor paid Uber a visit, asking for a meeting within two days to address a litany of complaints against the company. The local authorities wanted Uber to use only drivers with taxi licences and operate only yellow vehicles, something that Uber saw as a major barrier to recruitment.

"Looks like we need to ramp up our alliances on the ground, and fast," MacGann wrote after learning about the investigation.

Other threats loomed. Under the heading "growing pressure," an October 2015 summary of Uber's position in Russia also listed investigations from a federal anti-monopoly authority, a tax agency and prosecutors in St. Petersburg.

But Uber was beginning to make headway and lock in allies. Usmanov had invested, and talks were underway with LetterOne. Uber and Sberbank had signed a publicly announced deal to work together on mobile payments and vehicle financing. An executive at the bank promised to speak to the Moscow official who had demanded the investigation and explore the possibility of a meeting between Uber and the mayor of Moscow, an Uber executive wrote in an email after the agreement was signed. US authorities had placed limited sanctions on Sberbank, but Uber's lawyers advised in December 2015 that they wouldn't get in the way of the agreement, according to an email.

Then, in Davos for the 2016 edition of the World Economic Forum, Kalanick personally helped reel in LetterOne's investment. Kalanick met Alexey Reznikovich, the managing partner of LetterOne Technology, at the five-star Belvedere Hotel, according to his calendar.

"TK did great job at getting Alexey comfortable - created strong contact," MacGann wrote.

Reznikovich did not respond to requests for comment.

In February, the deal was signed. Uber agreed that LetterOne could publicise the investment, a break from its usual practice. But in a news release, Kalanick only hinted at what Uber saw as the major value of the partnership, saying, "L1's knowledge of emerging markets will be crucial”.

Unmentioned: A US$50 million side deal with LetterOne in the form of warrants - financial instruments that typically allow the holder to buy more stock at favourable prices - designed to incentivise LetterOne to help Uber grow in Russia, according to company emails describing the deal.

Hazelbaker said even if LetterOne "did nothing" it could have still used the warrants, and that they were tied to "Uber's relative growth in Russia, as measured by the number of trips happening in the country”.

In a recent interview, Aven, who resigned as a LetterOne director earlier this year, said he recalled one meeting with an Uber employee but was not involved in the investment in the company. He said he did not lobby on Uber's behalf.

"I can give you a comment because it's easy," he said. "I was not involved with Uber at all”.

Fridman, who also resigned as a LetterOne director this year, said his involvement with Uber also was minimal.

"Except for my very short meeting with Kalanick, I was not involved with the Uber investment or with any lobbying," Fridman said in a recent interview.

A spokesperson for LetterOne also said the company did not engage in any lobbying, and the decision to hire any lobbyist was Uber's.

"L1 became a modest strategic investor in Uber's multibillion-dollar funding round on the basis of Uber's potential in Asia and Russia," the spokesman said.

But to Uber leaders, the partnership quickly proved its worth. Within weeks, they were crediting LetterOne and Sberbank with helping Uber and the Moscow authorities reach an operating agreement, emails show, easing one major source of pressure on the company. Uber agreed to use cars with taxi licences and share some data with the local government but avoided requirements such as having to operate yellow vehicles.

With allies in place and the Moscow authorities at bay, MacGann and one of Uber's outside advisers began crafting a strategy in a document titled "taming the bear." The focus was passing a favourable federal law through the Duma that would allow Uber to grow relatively unchecked by limiting the power of regional authorities to require cars of a particular color or cap the number of taxi licences.

"The team believes that we should get organised, and fast, for an effective and comprehensive all-out lobbying campaign," they wrote in a draft memo outlining the plan.

Experts on Russian politics said Aven and Fridman's influence by 2016 was likely not substantial, but Uber's leaders were optimistic nonetheless. In an email, MacGann described the men as being part of a circle of the top 20 people who mattered in Russia.

"Having allies such as Aven, Gref and Fridman is quite unprecedented for a foreign (and US to boot) business seeking to disrupt the status quo in Russia and generate substantial income," MacGann wrote.

The new investors from LetterOne were keen to help - with one addition.

They proposed having Vladimir Senin, an executive at a bank they also ran, serve as Uber's lobbyist at a cost of US$50,000 a month, according to emails among Uber leaders describing the pitch. The proposal troubled Uber's leadership team, including Whetstone, who urged colleagues in emails to be sure they considered other consultants.

"I don't want to have our agencies decided by outsiders or to appoint an agency without a tender between three or four firms so that we know we have the best fit at the best cost," she wrote.

The potential cost, which at one point in the discussions with Senin ballooned to a proposed US$800,000 for about 7 months' work, also became an issue.

"It is so much money," Whetstone wrote. "Can we negotiate. Basically over 100k a month which I would never normally pay”.

Whetstone declined to comment on the specifics of her involvement with Uber's business in Russia. She said in general that she "consistently pushed back on Uber's more aggressive business practices."

Senin did not respond to requests for comment.

Uber's lawyers also raised concerns about the arrangement, according to a summary of their guidance, written by Uber executive Fraser Robinson. They worried about the possibility that Senin would take actions for which the company would be legally responsible.

"Ultimately there is no absolute way to prevent this, but the best we can do will most likely be to speak to L1 and tell them that they need to make 200% clear to Senin that any bribes will not be tolerated, and that we may hold the discretionary warrants as collateral," Robinson wrote to MacGann.

Robinson declined to comment.

In an April 2016 email, an Uber lawyer wrote that it would be preferable for LetterOne itself to be responsible for the lobbying. Otherwise, Senin and his team should be required to undergo compliance training and provide documentation of their activities.

Just as MacGann had labelled some of the legal advice too conservative, Benjamin Wegg-Prosser, an outside adviser to Uber, called the idea "totally absurd”.

"I see this all the time from idiot lawyers in the US who think that the world should work like a suburb of Seattle," he wrote to MacGann.

In a statement, Wegg-Prosser's firm, Global Counsel, said its work for Uber's European team "was undertaken in adherence with all relevant EU and UK guidelines”.

Ultimately, Uber agreed to hire Senin in a deal worth up to US$650,000. A draft of his contract included the training requirement and a pledge that he would not violate anti-corruption laws. Hazelbaker said a contract Uber found in its records "contains robust anti-corruption provisions”.

In response to questions, MacGann said he had concerns at the time about the amount Uber was being asked to pay Senin.

"This was clearly irregular," he said. "I made my concerns clear to the management team in San Francisco, including to my direct boss at the time."

But the company was up against a deadline, fearing that in Duma elections in the fall a key sympathetic lawmaker might lose his seat.

RICHARD DREW/AP

The logo for Uber appears above a trading post on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange.

In the spring of 2016, Uber's team in Europe began planning for Kalanick to come to Moscow. He had already met some of Uber's key partners at Davos and hosted Gref at the company's San Francisco headquarters, but now it was time to visit them on their home turf.

The trip would illustrate how closely tied politics and business were in Russia, with Kalanick often sharing a table with corporate leaders and top government officials.

"God love the Russians, where business and politics are so cosy," MacGann wrote.

Even though it was June, Kalanick's first night in Moscow was as cold, he said, as the coldest day in California. Huddled under red blankets or wearing coats, a crowd of about 1700 people had turned out to see Kalanick explain how Uber could help bust Moscow's traffic - "probki," as he had learned Russians called it. Kalanick, wearing a borrowed jacket, delivered his presentation awkwardly before taking questions.

A reporter from a Russian outlet struck right at the heart of one of Uber's biggest challenges in Russia: the stiff competition from other operators.

"Your ambitious plan about Russia and changing the traffic situation, are they real?" the reporter asked. "Uber honestly is nowadays one of the smallest taxi apps. I'm sorry for that, but we have Yandex Taxi."

"Boo," Kalanick said, talking over her. "It's OK, it's OK."

Yandex's taxi company was a branch of the Russian tech firm, which also ran a search engine and mapping service. In internal reports, Uber estimated that in March 2016, Uber was conducting 420,000 trips per week to Yandex's 750,000. Uber executives saw potential for working with Yandex but also found the Russian company unwilling to join its lobbying efforts.

On Monday morning, Kalanick met with one of Russia's deputy prime ministers at a pizzeria before heading across town to Fridman's offices. Kalanick might have boasted about cutting traffic, but to get to the dinner with Gref on time, his team decided they would have to take the Metro.

"Good news: we took metro and it meant we were on time for Gref influencer dinner instead of 45 minutes late," MacGann texted Whetstone. The bad news, he said, was that they had passed through stations that looked like some of the grimmer parts of London, rather than the palatial ones for which Moscow is famous.

The visit ended the next morning on an inauspicious note: Kalanick overslept and forgot his phone at the hotel.

GETTY IMAGES

Russia showed that there were parts of the globe that Uber simply couldn't conquer.

The week before Kalanick's visit, Uber had hired an in-house government relations executive in Russia. Marat Murtazin had held a similar role with oil giant BP. That meant he had an awkward history with Fridman and Aven, who had used the proceeds from a collapsed joint venture with BP to launch their investment firm.

As Murtazin got to grips with Uber's position in Russia, he soon began to question whether Senin was doing the lobbying work he claimed. Other Uber executives, including Whetstone, were also concerned about Senin's performance.

"I think that we let Senin to play a guaranteed win lottery without even making him to pay for a lottery - ticket," Murtazin wrote to Robinson in his idiosyncratic English.

Murtazin did not respond to requests for comment.

By July 2016, Uber had decided to end Senin's contract. But it was a delicate subject, because some company leaders feared it would alienate Aven, his patron. They ultimately paid him US$300,000, leaving Senin "very happy," according to Murtazin.

"What an absolutely terrible waste of money," MacGann wrote to Murtazin.

Hazelbaker confirmed Senin was paid.

"We certainly would not engage with Senin today," she said.

The prospects of the taxi law passing before the election were also slipping away as different factions battled over its contents. Uber's team decided to regroup and develop a plan for the new session of the Duma. The taxi law was never passed, according to the Duma's records.

In June 2017, Kalanick resigned as chief executive after a wave of allegations about sexual harassment at Uber. Within weeks, Uber had signed a deal to form a joint venture controlled by Yandex, marking the end of its efforts to expand in Russia. Uber began winding down its involvement in that venture in 2021, accelerating its efforts after Russia's invasion of Ukraine in February. Fridman and Aven's LetterOne later sold its stake in Uber at a loss, according to Russian media reports.

Just as the company's buccaneering culture had finally caught up with Kalanick, Russia had shown that there were parts of the globe that Uber simply couldn't conquer.

The Washington Post