The concept of the ‘witch’ draws from the European Wicca traditions. Wicca is a Neo-pagan religion that was introduced to the world in a codified form in 1945 by former British civil servant Gerald Gardner.

Outlook Web Desk

UPDATED: 13 APR 2022

We have all grown up with images of the scraggly witch on a broomstick in a pointy witch’s hat. Or the Indian witch or ‘dayan’ with bulging eyes, reversed foot and knotted unruly hair. The myth of witches has existed in India ever since time immemorial. Be it the ‘chudail’ or ‘Pichal Pairi’ of North India, Pishachini or Petni of West Bengal, or simply ‘Dayan’, the idea of the witch in either a demonic form or in the form of an evil priestess has been popularised in countless folk tales, films and pulp fiction horror stories. But much of the representation of witches in Indian films and literature is largely inaccurate. This is due to reasons — one is the misunderstanding of witches and witchcraft, and the second is patriarchy. Nevertheless, witches have usually been the demon of choice when it came to feminists representing themselves through the horror metaphor.

The concept of the ‘witch’ draws from the European Wicca traditions. Wicca is a Neo-pagan religion that was introduced to the world in a codified form in 1945 by former British civil servant Gerald Gardner. However, its origins can be traced to pre-Christian times. It encompasses various denominations and sects that are based on witchcraft and the duo theistic worship of the Supreme Gods and God. The religion is characterised by various rituals and was the first to formally acknowledge the pagan community of witches (men and women) that existed and practised for ‘Witchcraft’. While the community represented more than just witches, later representation in pop culture associating Wicca with cauldron swilling pagan witches further solidified the idea of Wiccan witches. Many followers of Wicca claim to believe in “magic” as a science. As performative magician and occultist Alistair Crowley had put it, magic is “the science and art of causing change to occur in conformity with will”.

The Witch’s Tale: Women In Indian Horror Films

In 1968, a manifesto by a women's group called WITCH read, "Witches have always been women who dared to be: groovy, courageous, aggressive, intelligent, nonconformist, explorative, curious, independent, sexually liberated, revolutionary...You are a witch by being female, untamed, angry, joyous and immortal". Thus witches have been a socio-political statement for women as much as a horror staple.

There is a thriving Wiccan witch community in India. The country’s first noted openly Wiccan witch was Ipsita Ray Chakravarty, daughter of a diplomat who grew up in Canada. According to interviews, she felt her first supernatural experience at the age of 10. In the late 80s, Chakravarty started speaking about the ancient tradition of witchcraft in India and has often spoken sternly against the representation of witches in Indian films as monstrous ‘dayans’.

The Wiccan tradition is what gives us the witch on a broomstick with a pointy hat trope. Today, many women in India claim Ito follow witchcraft. A thriving community of Wiccan witches on social media exists in which women not only talk about their experiences with witchcraft but also sell ‘magical’ items like totems, spells, incantations, even wands. The Harry Potter series of books also brought a new perspective on witches for urban Indian audiences who came face to face with anthropomorphised teen witches and wizards.

Nevertheless, the myth of the ‘Daayan’, the desi and monstrous version of the witch has remained popular in Indian horror films. Recent retellings o the witch’s tale have seen writers and directors experiment with themes of sexual violence and patriarchy to subvert the horror plots creating ‘daayans’ out of victims of patriarchy.

But the witch’s influence in Indian films and literature goes further back than just fiction or folk tales. In India, witchcraft is deeply rooted in Vedic Hindu religion. Witchcraft - or tantra Sadhna, is a pre-Vedic tradition part of the Tantra sect of Hinduism. Its followers, called Tantriks and Tantrikas, as often associated with witchcraft. While the men have been termed ‘sadhu’ or ascetic, however, women have often been dubbed as ‘witches’.

In fact, Daakinis and tantrikas were among the original healers before organised religion. According to Anubhuti Dalal, a practising Tantrik, daakinis have the ability to use magic, concoct potions and use their knowledge of herbs and poisons to heal people of both physical, and mental and metaphysical afflictions. They could make women stay young forever and make men fall in love. They could fix a broken heart or heal an infected body. This kind of manifestation of women’s power to manipulate energy has been recorded across the world including in Europe where a community of pagan witches have long existed under the Wiccan tradition. Witch societies are today studied through a feminist lens in that they have historically provided a safe space for women that organised religion could not provide.

In that way, the Indian Tantrik tradition has been similar to Wicca in providing a safe space and sisterhood to women within the community. Witches or practitioners of witchcraft often have their own language and ways of communication.

“A village daakini, before anything, is a friend of the persecuted women. She was supposed to be the custodian of women’s rights at a time when women had no representation. She could punish men for their wrong-doings, set things right for the woman at her household and empower them with justice,” adds Dalal. Dakinis, like Wiccan witches, are also known to be great doctors. Researchers of Wiccan witch rituals found that the ‘spells’ and recipes used by witches often use scary code names for herbs and plants. Newt’s eyes and dogs’ tongue - the famous ingredients used by Macbeth’s witches, for instance, actually refer to mustard seeds and the highly toxic plant houdstounge.

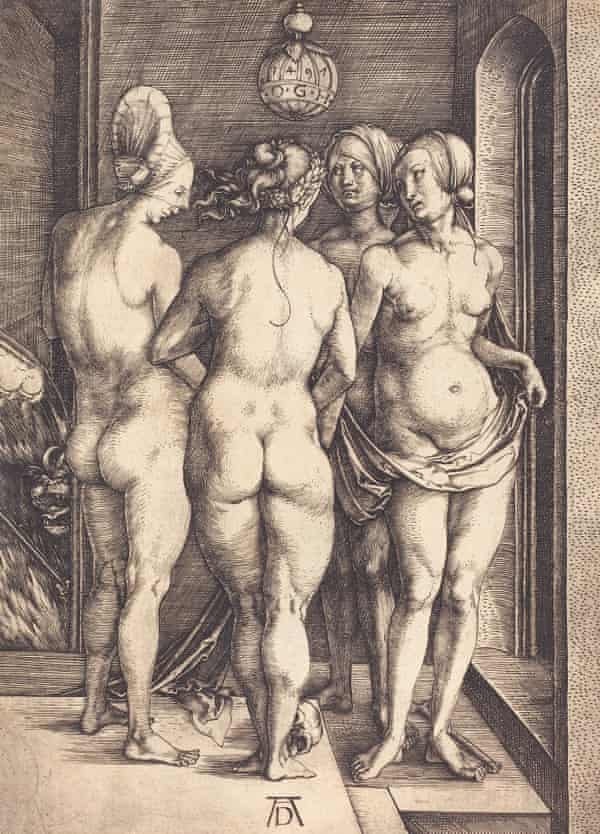

The Modern Witch Trials era in the West during which scores of women were burnt at the stake across England and other Anglo-Saxon countries vilified witches as sorceresses worshipping the Horned God. Later, Gardern's reiteration of Wicca brought forth evidence of the worship of the Mother Goddess - representing life and fertility - thus helping pagan witches destigmatise their image and move away from the Shakespearean representation of evil witches to a more free-spirited, pagan witch who used magic for good rather than evil.

Both Dalal and Wiccan witches like Ipsita have objected to the representation of witches in India. The skewed narratives of women in Indian (as well as Western) horror films and literature is an expression of the internalised cultural beliefs, mythology and pop culture. But today, women writers and filmmakers have tried to take over the genre and write stories that depict the witch not as a monster but as an avenger and vigilante. The change in tonality can be seen as a reflection of the growing empowerment of women and acknowledgement of culture and mythology as important building blocks of gender roles.

Related Stories

Horror As An Allegory: The Ghosts Within

Fear Of The Known: Socio-political Themes In Marathi Horror Cinema

.jpeg;w=960;h=640;bgcolor=000000)

.jpeg;w=960;h=640;bgcolor=000000)

.jpeg;w=960;h=640;bgcolor=000000)