During the 18th and 19th centuries, most of those involved in commerce on China’s coast had connections to the opium trade, whether they like to admit it or not

A man smokes opium in Peking, with an attendant holding a tobacco pipe, circa 1905. Picture: Alamy

Opium – for numerous economic and political reasons – has loomed large in Asia for more than three centuries. Importation from India to China and the wider balance-of-trade dynamics, regional power struggles and eventual international conflicts that surrounded the trade have generated entire libraries of historical research.

Young American’s first-hand account of second opium war: bloody battles and ‘hospitable’ Chinese

Less acknowledged – especially by internet trolls who, like Pavlov’s dogs, salivate and bark at the slightest mention of the so-called opium wars – is the basic historical fact that virtually everyone involved in 18th- and 19th-century commerce on the China coast was connected with the trade. Individuals or firms were either directly involved or they brokered deals, banked or arranged letters of credit, or were tangled up in the shipping, refining and warehousing of opium, or its retail sale.

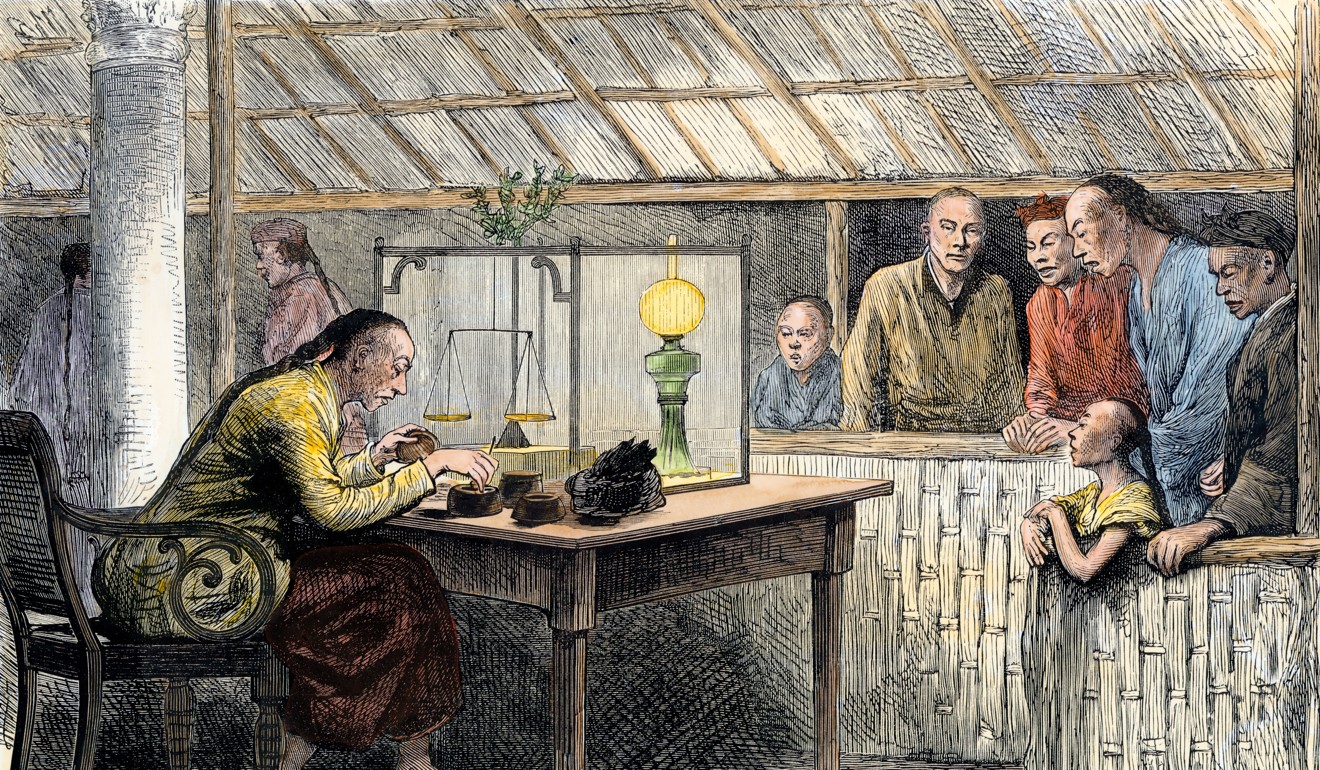

Opium being weighed in China in the 1880s. Picture: Alamy

Their descendants become skittish at any mention of their forebears’ business activities – the original source of their own affluence. Few are as principled as, say, Austrian-British mathematician and philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, who renounced a family fortune made in steel production and the armament industry; that repudiation would be a bridge too far, especially for “pragmatic” Hongkongers. Corporate “histories” that document local firms and their founding families with connections to the opium trade usually airbrush out inconvenient facts and play down those that can’t be completely hidden while retaining any credibility.

The Opium war (or how Hong Kong began)

Finding businessmen of any ethnicity who were not involved is a challenge. Prominent among this tiny minority was Olyphant and Co; and the firm’s co-founder, David Olyphant, who was a vocal opponent of the opium trade. This stance was responsible for its Canton offices being known to competitors as “Zion’s Corner” – a snide reference to the moral standpoint maintained by the company’s American principals.

As well as Canton, the firm had offices in Hong Kong, Shanghai, Foochow (principally for the tea trade), Australia and New Zealand. Olyphant and Co dealt mainly in silk, hessian and other heavy fabrics; it also owned a small fleet of clippers used primarily to transport tea and silk to the United States. Due to a reduction of business activity in China, and a series of ill-advised investments in Peru, the firm collapsed in 1878.

How cotton once rivalled opium in importance for Hong Kong – and helped build city’s textile trade

H.N. Mody, co-founder of Kowloon Wharf and Godown Co and opium trader.In Hong Kong, the Tung Wah Hospital, established in 1870, numbered many opium-merchant philanthropists among its early committee, which was drawn from the Chinese community. Opium, for them, was just one of many profitable enterprises, which ranged from dealing in cotton and dried seafood, medicinal herbs and preserved foodstuffs to pawnbroking, remittance services and emigrant passage agency.

China, by the mid-1920s, produced more opium, mainly in Yunnan and Sichuan, than ever had been imported from India, Persia and elsewhere. And this latter-day trade was almost entirely in Chinese hands. Government corruption played a key part. Opium suppression movements in the 30s were just so much tawdry political theatre, with the most enthusiastic anti-drug campaigners often being the greatest profiteers. “Keyboard warriors” looking for a convenient anti-foreigner starting point for their ravings neatly overlook all these facts.

The University of Hong Kong’s Main Building, pictured in 1911, was built with funds donated by Parsee businessman H.N. Mody.

Like all social evils, some lasting good came from opium-trade investments and the economic diversification that followed. To cite one example, H.N. Mody, Hong Kong’s leading late 19th-century Parsee businessman, the co-founder of Kowloon Wharf and Godown Co (now part of the Wharf conglomerate) and an opium trader, was a major early benefactor of the University of Hong Kong; its Main Building, opened in 1912, was personally paid for by him.

No comments:

Post a Comment