An ancient vertebra from an archaic hominin species child gives ‘unambiguous’ evidence of migrations out of Africa, Israeli researchers say

The 'Ubeidiya archaeological site in the Jordan Valley, where researchers found a 1.5 million year old human vertebra. (Courtesy/Dr. Alon Barash)

An international group of Israeli and American researchers has discovered a vertebra from a hominin species dated to 1.5 million years ago that lived in the Jordan Valley. The bone was from a child aged 6-12 and is the most ancient evidence of a human presence in today’s Israel, as well as the second oldest human remain found outside of Africa.

The stunning find shines light on the most ancient human migrations out of Africa by offering a sign that multiple waves of different hominin species left the continent, the researchers said in an article published Wednesday in the prestigious peer-reviewed Scientific Reports journal.

“We now have unambiguous evidence of the presence of two distinct dispersal waves,” said the researchers.

Human evolution can be traced back around 6 million years through fossil and DNA evidence. Hominins are primates that are modern humans’ direct ancestors or closely related to us. Homo sapiens, our modern form, does not appear in the fossil record until around 200,000 to 300,000 years ago.

Evolution is not a straight path, but a tree, with many branches leading nowhere. It occurs on a long continuum and there have been many hominin species that went extinct, the most famous being the Neanderthals. (The famous ancient skeleton dubbed “Lucy,” found in Ethiopia in 1974, was a pre-Homo sapiens hominin from 3.2 million years ago.)

Get The Times of Israel's Daily Editionby email and never miss our top stories

Newsletter email addressGET IT

By signing up, you agree to the terms

Around 2 million years ago, there is evidence that some archaic human species began to leave Africa. The first human remains of groups that left Africa were found in modern Georgia in the Caucasus region and are dated to around 1.8 million years ago. Archaeologists found their remains and tools at a site called Dmanisi.

The new vertebra found in Israel is evidence of a second wave out of Africa by another species hundreds of thousands of years later, the researchers said.

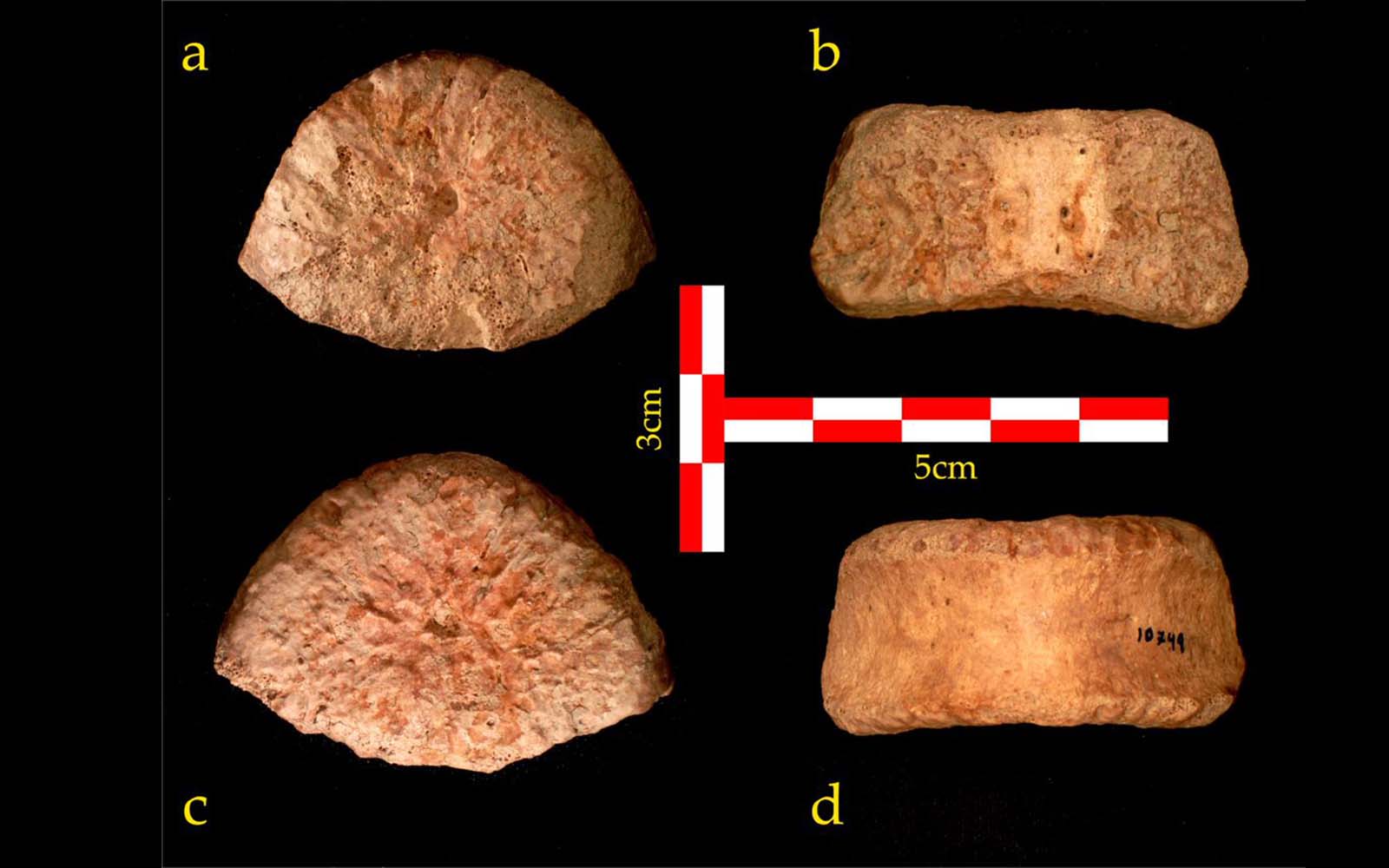

The top (a), rear (b), bottom (c) and front (d) view of the vertebra discovered at the ‘Ubeidiya site. (Courtesy/Dr. Alon Barash)

Archaeologists found the tiny bone in 1966 at a prehistoric site called ‘Ubeidiya, near Kibbutz Beit Zera, just south of the Sea of Galilee. During these previous excavations from 1960 to 1999, archaeologists uncovered ancient stone and flint tools that resemble finds in eastern Africa; extinct animal bones including sabertooth tigers, mammoths and giant buffalo; and bones from species no longer in the region, including baboons, warthogs, hippopotamuses, giraffes and jaguars.

ADVERTISEMENT

For the new study, researchers renewed excavations at the site and made use of new technology to better classify and date previous finds.

The ancient child’s vertebra was discovered while examining fossils from the previous excavations that are kept at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The bone had previously been examined but had not been identified.

They identified it as a human lumbar vertebra, from the lower part of the back, dating to 1.5 million years ago.

The researchers said there is an ongoing debate over whether humans left Africa at once, or in multiple waves, and the new find supports the second theory, since it appeared to be from a different human species than the skeletons in Georgia.

A pre-human skull found in 2005 in the ground at the medieval village Dmanisi, Georgia, pictured on October 2, 2013. (AP Photo/Shakh Aivazov)

Stone tools found in Georgia and at the Israeli site were also different. Researchers initially believed they were produced by two different cultures, but in the new report, the archaeologists said they were likely made by different species.

The new study also uncovered that the two known sites of early human habitation had divergent climates that contributed to the distinct cultures.

ADVERTISEMENT

“One of the main questions regarding the human dispersal from Africa were the ecological conditions that may have facilitated the dispersal. Our new finding of different human species in Dmanisi and ‘Ubeidiya is consistent with our finding that climates also differed between the two sites. ‘Ubeidiya is more humid and compatible with a Mediterranean climate, while Dmanisi is drier with savannah habitat,” said Prof. Miriam Belmaker of the University of Tulsa, whose grant facilitated the new excavations.

Study researchers from left to right: Dr. Omry Barzilai, Y. Merimsky, who discovered the prehistoric site at ‘Ubeidiya, Prof. Miriam Belmaker and Dr. Alon Barash (Bar-Ilan University)

The Israeli researchers’ analysis showed the bone found in Israel was from an individual who was between 6 and 12 years old at his time of death. He was tall for his age, and would have reached around 5 feet 9 inches tall (180 cm) as an adult.

His size was similar to other large hominins in eastern Africa around the time. The species in Georgia was shorter, the researchers said.

“It seems, then, that in the period known as the Early Pleistocene, we can identify at least two species of early humans outside of Africa,” said Dr. Alon Barash of Bar Ilan University, one of the lead researchers.

“Each wave of migration was that of different kind of humans — in appearance and form, technique and tradition of manufacturing stone tools, and ecological niche in which they lived,” he said.

The study was led by researchers from Bar-Ilan University, Ono Academic College, the University of Tulsa and the Israel Antiquities Authority.

Vertebra discovered in the Jordan Valley tells the story of prehistoric migration from Africa

A new study published in the journal Scientific Reports, suggests that ancient human migration from Africa to Eurasia was not a one-time event but occurred in waves.

The first wave reached the Republic of Georgia in the Caucasus approximately 1.8 million years ago. The second is documented in ‘Ubeidiya in the Jordan Valley about 1.5 million years ago.

The research was led by Dr. Alon Barash of the Azrieli Faculty of Medicine of Bar-Ilan University, Professor Ella Been of Ono Academic College, Professor Miriam Belmaker of The University of Tulsa, and Dr. Omry Barzilai of the Israel Antiquities Authority.

According to fossil evidence and DNA research, human evolution began in Africa about six million years ago. Approximately two million years ago, ancient humans (nearly, but not yet in modern form) began to migrate from Africa and spread throughout Eurasia, a process known as the “Out of Africa.” ‘Ubeidiya, located in the Jordan Valley near Kibbutz Beit Zera, is one of the places where we have archaeological evidence for this dispersal.

The prehistoric site of ‘Ubeidiya is significant for archaeological and evolutionary studies because it is one of the few places that contain preserved remnants of the early human exodus from Africa. The site is the second oldest archaeological site outside Africa and was excavated by several expeditions led by Professor M. Stekelis, Professor O. Bar-Yosef, and Professor E. Tchernov between 1960 and 1999.

The finds from the site include a rich and rare collection of extinct animal bones and stone artifacts. Fossil species include sabertoothed tiger, mammoths, and a giant buffalo, alongside animals not found today in Israel, such as baboons, warthogs, hippopotamuses, giraffes, and jaguars. Stone and flint items made and used by ancient humans show resemblance to those discovered at sites in East Africa.

Recently, excavations in ‘Ubeidiya were resumed by Belmaker and Barzilai under a grant that Belmaker received from the U.S. National Science Foundation. The project uses new absolute dating methods to refine the site’s dating and to study the paleoecology and paleoclimate of the region. While looking at the fossils from the site, now housed at the Hebrew University’s National Natural History Collections, Belmaker, a paleoanthropologist from The University of Tulsa’s Department of Anthropology, encountered a human vertebra. Initially unearthed in 1966, the bone was studied by Barash and Professor Ella Been. They identified it as a human lumbar vertebra, the earliest fossil evidence of ancient human remains discovered in Israel, approximately 1.5 million years old

According to Barash, human anatomy and evolution researcher at the Azrieli Faculty of Medicine of Bar-Ilan University, there is an ongoing debate in the literature about whether the migration was a one-time event or occurred in several waves. The new find from ‘Ubeidiya sheds light on this question. “Due to the difference in size and shape of the vertebra from ‘Ubeidiya and those found in the Republic of Georgia, we now have unambiguous evidence of the presence of two distinct dispersal waves.”

According to Barzilai, head of the Archaeological Research Department at the Israel Antiquities Authority, “The stone and flint artifacts from ‘Ubeidiya, handaxes made from Basalt, chopping tools, and flakes made from flint, are associated with the Early Acheulean culture. Previously, it was accepted that the stone tools from ‘Ubeidiya and Dmanisi were associated with different cultures – Early Acheulean in ‘Ubeidiya and Oldowan in Dmanisi. After this new study, we conclude that different human species produced the two industries.”

Belmaker explained, “One of the main questions regarding the human dispersal from Africa were the ecological conditions that may have facilitated the dispersal. Previous theories debated whether early humans preferred an African savanna or new, more humid woodland habitat. Our new finding of different human species in Dmanisi and ‘Ubeidiya is consistent with our finding that climates also differed between the two sites. ‘Ubeidiya is more humid and compatible with a Mediterranean climate, while Dmanisi is drier with savannah habitat. This study showing two species, each producing a different stone tool culture, is supported by the fact that each population preferred a different environment.”

“The analysis we conducted shows that the vertebra from ‘Ubeidiya belonged to a young individual 6-12 years old, who was tall for his age. Had this child reached adulthood, he would have reached a height of over 180 cm. This ancient human is similar in size to other large hominins found in East Africa and is different from the short-statured hominins that lived in Georgia,” said Been, paleoanthropologist at the Ono Academic College Faculty of Health Professions and an expert in spinal evolution.

“It seems, then, that in the period known as the Early Pleistocene, we can identify at least two species of early humans outside of Africa. Each wave of migration was that of different kind of humans –– in appearance and form, technique and tradition of manufacturing stone tools, and ecological niche in which they lived,” concluded Barash.

Ubeidiya - Image Credit : Hanay - CC BY-SA 3.0

Ruth Schuster

Feb. 2, 2022 12:04 PM

About 1.5 million years ago, a child died near the Sea of Galilee. All that remains of the youngster is a single bone, a vertebra. But that skeletal fragment, first unearthed in 1966 and only now recognized for what it actually is – the earliest large-bodied hominin found in the Levant – changes the story of human evolution.

Among other things, that one bone proves for the first time that there were multiple exits by archaic humans from Africa. At 1.5 million years of age, the bone is the second-oldest hominin fossil to be found outside Africa. The oldest date to 1.8 million years ago and were found in Dmanisi, Georgia, and that difference of about 300,000 years proves in and of itself that there was more than one exit.

More? This archaic child in the Jordan Valley and the hominins at Dmanisi were not the same species.

The study on the vertebra, which is by far the oldest hominin fossil in Israel, was published Wednesday in Scientific Reports by an international team led by Dr. Alon Barash of the Azrieli Faculty of Medicine of Bar-Ilan University, Prof. Ella Been of Ono Academic College, Prof. Miriam Belmaker of the University of Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Omry Barzilai of the Israel Antiquities Authority.

Open gallery view

The site at Ubeidiya.Credit: Dr. Omry Barzilai / Israel Antiquities Authority

Ecce homo?

The story of the bone begins in 1959, when a member of Kibbutz Afikim named Izzy Merimsky was bulldozing land in preparation for agriculture and, Barash explains, suddenly observed that his machine was unearthing human bones, including a skull and teeth.

No, those did not belong to the ancient child. We don’t know what they were because they were hopelessly out of archaeological context, Barash explains. They could be incredibly ancient or from some recent local flare-up. Maybe one day that will be cleared up.

Early Homo sapiens found in Ethiopia is older than had been thought

The human brain shrank 3,000 years ago. Now we know why

Anyway, being archaeologically aware, Merimsky called in the authorities. Excavation began in 1960 and it became clear that the site was deeply prehistoric. Subsequently, in 1966, the archaeologist Moshe Stekelis unearthed the vertebra in situ that would change the story of human evolution. But not right away.

Said vertebra had been found with animal bones. “For some reason,” Barash says, “it was placed in a box marked ‘Homo?’ – with the question mark – and forgotten. It was ignored. It was put with monkey bones.”

Moving onto the 2020s and University of Tulsa paleoanthropologist Miriam Belmaker, who was working with the Antiquities Authority’s Barzilai on reconstructing the paleoclimate at prehistoric Ubeidiya, and embarking on the tortuous process of trying to date the site with accuracy. “It’s a work in process,” Barash observes.

In the hope of resolving the dating conundrum, Belmaker reanalyzed all the animal fossils found at the site, which are indicative of climate. (If a tropical animal is found, the area wasn’t glaciated, to be extreme about it.) She rediscovered that backbone bit, suspected it was not a monkey, and called in Barash the paleoanthropologist, Barzilai relates. One look sufficed for Barash to know that an ape, it was not.

Open gallery view

Homo erectus

That look was followed by a vast amount of comparative research on the vertebrae of ancient hominins, modern humans, hyenas, rhinos, lions, apes and other animal suspects that had all been present in Ubeidiya, say Barash and Ono College's Prof. Been. And this is what they found.

“It was not an australopithecine and not an elephant and not a gorilla and not a mermaid – we measured a ton of vertebrae. It has distinct features. It was a large-bodied bipedal hominin,” Barash says.

Even before the vertebra resurfaced and was reclassified as a fragment not of monkey or merperson but of extremely ancient hominin, Ubeidiya had been believed to date back to 1.5 million years, based on stone tools unearthed there thanks to that observant kibbutznik who just meant to clear land to grow something or other, Barzilai says.

Analysis of the bone was done with Been, an expert on paleoanthropology who explains that having thoroughly studied the vertebrae of every animal that moved in Ubeidiya at the time, and decided it was a hominin, they then considered what part of the hominin’s back it came from. Morphometric analysis showed the bone was one of the lower three lumbar vertebrae.

“In bipeds, these vertebrae have a unique structure,” Been explains. “The anterior part is tall and posterior part short” (because in bipeds, the lower back is load-bearing). “In this one, the anterior part was tall and the posterior part was short, which we don’t see in monkeys or apes, which are not bipedal.”

The question is, which hominin was this child? One hint lies in the tools found at Ubeidiya, which were classified as relatively advanced Acheulean-type, not primitive Oldowan – which is hugely significant. (Yes, there were extremely primitive stone tools as much as 3.3 million years ago, but we have no idea who the toolmaker was, Barash points out, and shall leave that out of our story.)

Open gallery view

Omry Barzilai from the Antiquities Authority.

Confusion in the Caucasus

It is believed that the Homo line (culminating in us) split from the Pan line (culminating in the chimpanzee) 7 million to 6 million years ago. Until recently it was thought that after the split, human evolution was linear.

It was not. We now realize there were multiple types of hominins, some living contemporaneously with one another and, as of 2 million years ago at least, roaming out of Africa.

The oldest hominin fossils found to date outside Africa are just over 1.8 million years old, in Dmanisi; and now we have this individual from 1.5 million years ago in Israel. So, first of all, clearly there was more than one hominin migration out of Africa. There could have been dozens, there could have been constant creep, in both directions – we simply don’t know. The fossil evidence of our prehistory is incredibly sparse and stone tools can only tell us so much.

We also can’t say how many hominin species there were in Africa when the ancestors of the Dmanisi crew exited. But among the earliest members of the Homo line in Africa was Homo habilis, which lived from perhaps 2.3 million to 1.6 million years ago. And following on its very heels, we find a new species – Homo erectus, – Barash explains.

The chimp brain is about 300 to 400 cubic centimeters in volume. Australopithecus was no larger than a chimp and had only a slightly bigger brain: perhaps about 450 cc. In other words, no great difference. Australopithecines were weeny, too, with the famed Lucy estimated to have been a meter tall (3 feet, 3 inches). Some think maybe 1.20 meters, which is still wee. Still no great distance from the chimp.

Homo habilis was a step along, with a brain about 600 to 700 cc. in volume but was also short, a few centimeters taller than Lucy. Then come the next species: erectus was a giant, relatively to its predecessors. It was beefier and taller, with a bigger brain, about 800 to 900 cc, Barash explains.

Open gallery view

A skull of Homo habilis.Credit: Rama

In addition, Homo habilis in Africa was found in association with the primitive, early Oldowan-type tools. Homo erectus in Africa was found in association with more advanced Acheulean-type tools: hand-axes, choppers and the like.

Now for a twist. Who exactly was found at Dmanisi?

Good question. The Georgian authorities simply deflected any classification enigmas by dubbing their being Homo georgicus. Many simply assume it was a variant of erectus. But in fact they were small-bodied and had small brains, Barzilai points out.

Reconstruction of Homo georgicus showed them to be much shorter than erectus, he observes. Moreover, the stone tool culture found there is primitive Oldowan-type, not advanced Acheulean.

Yes, the team suspects that Dmanisi Person, aka Homo georgicus, arose from Homo habilis expanding out of Africa around 2 million years ago and reaching central Asia and perhaps beyond. Though while about it, Barash makes things even messier: there is no consensus that the creatures at Dmanisi belonged to a single species, he says.

“The bottom line is that georgicus were definitely not Homo erectus,” he says. “For one thing, their brains were too small. If you took the Dmanisi skulls and put them in an African context, you would clearly see – it’s habilis.”

Fine. How the habilis or whoever it was got to Dmanisi, we do not know. Israel and the Levant are the natural land bridge between Africa and Eurasia, but no fossil hominin bones from that deep prehistory have ever been found in Israel or anywhere in the Levant. Nor have sites that could be 2 million to 1.8 million years old, going by tools. Which doesn’t necessarily mean habilis didn’t pass through here 2 million to 1.8 million years ago, just that we haven’t found the evidence.

Open gallery view

A skull of Homo erectus.Credit: Tiia Monto

But now, from 1.5 million years ago, associated with relatively advanced Acheulean-type hand axes, Israel has a bone. Whose bone? Erectus’ bone.

“It certainly belonged to erectus,” Barash states.

Let us be clear that this momentous discovery does not make our lineage any clearer. If anything, it’s muddier. We cannot say that habilis begat erectus which begat hominin races in Europe such as the Neanderthal. We have absolutely no idea which if any of these species were our ancestors.

But we can say that because Ubeidiya is 1.5 million years old and the tools are Acheulean, the person there was from a separate migration wave than the ones who wound up in the Caucasus.

One wonders why everybody and his dog assumes the Dmanisi specimens were erectus and are not commonly identified as habilis.

“Erectus used to be the waste basket – everything from 1.5 million years onward was called erectus,” Barash sniffs. Nowadays, the fashion is to split them: Homo ergaster, Homo antecessor, and so on. The rub is that actual evidence is beyond scarce. There are perhaps one or two samples of each, which is hardly enough to base speciation on; and may we note the vast variation that can exist within a species. (Pygmy versus Norwegian – need we say more?)

But Barash is sure that Ubeidiya Person is an erectus type. For one thing, despite being a child it would have been huge – not like the weedy, ape-like habilis that maybe would have weighed 30 to 40 kilograms (66 to 88 pounds) in adulthood and reached your waist. The only complete erectus skeleton ever found, in Kenya, was 1.8 meters (6 feet) tall – and it was young. This one in Israel would have been that tall too if it had survived to adulthood, the archaeologists estimate.

Open gallery view

Dr. Alon Barash from Azrieli Faculty of Medicine at Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan.Credit: Dr. Alon Barash

Prof. Been for one thinks its final height would have been more than 1.8 meters tall, which is their conservative estimate. It was big, and if anything bigger than the African erectuses, she says.

he died young

So there were multiple waves out of Africa; habilis and erectus, and who knows who else. Asked apropos of nothing for his opinion about the tiny small-brained “hobbits” of Southeast Asia, Homo floresiensis and Homo luzonensis, Barash doesn’t completely dismiss the possibility that they really did arise from a super-primitive species like Australopithecus who might have left Africa even earlier. However, he suspects they arose from habilises or erectuses that reached the region, and underwent dwarfism on the islands. Sapiens they were not.

Now back to northern Israel and that vertebra. Morphologically it was biped-type and hailed from the lower back, aka the lumbar region. And the being was big (“large-bodied”), Barash says.

How do they know 1.5 million years after the event, from a single bone, that it came from a juvenile? It hadn’t finished growing. Ossification was not complete.

Open gallery view

The site at Ubeidiya where the vertebra was discovered in 1966.Credit: Emil Alagem/Israel Antiquities Authority

Open gallery view

A 1.5 million-year-old flint cutting tool found in Ubeidiya.Credit: Dafna Gazit/Israel Antiquities Authority

In modern humans, the last bone to finish ossifying is the pelvis, at about age 25, he explains. The vertebrae ossify at about age 3 to 4. This vertebra was not completely ossified, so it came from a child. They think it may have weighed between 45 to 50 kilograms at death.

This particular one is estimated to have been aged somewhere between 6 and 12, but we don’t know how its species grew, he qualifies.

“Modern humans grow very fast from birth to age 3-4, then we grow more slowly, and then in adolescence we have another growth spurt. No other animal does that,” Barash explains. “We think Neanderthals also grew linearly. We suspect that here too.”

Based on extrapolation, they believe the child would have reached a considerable 1.8 meters in adulthood. Yes, that’s classic erectus territory and completely different from what we know from Dmanisi. Going by chimp standards, it could have towered to 1.92 meters in adulthood, the team adds.

Been also shares a personal story – how she became involved in the research. “I was born just 2.5 kilometers from Ubeidiya, in Kibbutz Alumot. When I was a small child, 3 or 4, my grandfather Moshe Zoref would pick up flint tools in the fields which could have been made by erectus! He would make knives out of them, using animal jawbones. He taught me how to use them and would tell me about ancient hominins. For me, this project was closing a circle,” she says.

So, what do we have? A child from a very large species of hominin, who in dying in northern Israel 1.5 million years ago provided the first proof that more than one species left Africa in multiple waves over 200,000 to 300,000 years.

Open gallery view

The site at Ubeidiya in northern Israel.Credit: Dr. Alon Barash

And then what happened, after habilis and erectus and who knows who else left Africa? We have no idea.

“Were there other waves before or after? We don’t know. We find elephants – maybe they followed the elephants to hunt them,” Barash says, going straight into the territory of his colleague at Tel Aviv University, Prof. Ran Barkai, who believes human evolution has close ties with our appetite for elephant.

Barash continues to throw little bombshells into this boiling pot of evolutionary spaghetti. Maybe the erectus and habilis met and interbred in Europe, he speculates for fun. And asked to confirm that, indeed, we have no indication that either of them are ancestral to us, he confirms it.

He also adds: we sapiens never were massive. We are a gracile lot, while the erectus and its ilk (and Neanderthals) were not only tall but burly. It is entirely possible that with all the recent discoveries and all the insights, we never have found our ancestor.

The earliest Pleistocene record of a large-bodied hominin from the Levant supports two out-of-Africa dispersal events

Scientific Reports 12, Article number: 1721 (2022)

Abstract

The paucity of early Pleistocene hominin fossils in Eurasia hinders an in-depth discussion on their paleobiology and paleoecology. Here we report on the earliest large-bodied hominin remains from the Levantine corridor: a juvenile vertebra (UB 10749) from the early Pleistocene site of ‘Ubeidiya, Israel, discovered during a reanalysis of the faunal remains. UB 10749 is a complete lower lumbar vertebral body, with morphological characteristics consistent with Homo sp. Our analysis indicates that UB-10749 was a 6- to 12-year-old child at death, displaying delayed ossification pattern compared with modern humans. Its predicted adult size is comparable to other early Pleistocene large-bodied hominins from Africa. Paleobiological differences between UB 10749 and other early Eurasian hominins supports at least two distinct out-of-Africa dispersal events. This observation corresponds with variants of lithic traditions (Oldowan; Acheulian) as well as various ecological niches across early Pleistocene sites in Eurasia.

Introduction

The Levant region, the major land bridge connecting Africa with Eurasia, was a significant dispersal route for Hominins and fauna during the early Pleistocene1,2,3. But while there are numerous Eurasian early Pleistocene sites, fossil hominin remains are rare and present only at four localities dated between 1.1 and 1.9 Mya4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11: Dmanisi (Georgia), Venta Micena (Orce, Granada), Modjokerto and Sangiran (Java, Indonesia), and Sima De Elefante (Atapuerca, Spain) (Supplementary 2: Table 1; Fig. 1a). In contrast, early Pleistocene east African sites containing Homo cranial remains are more abundant, but postcranial remains are scarcer, and the best-preserved skeleton is Nariokotome KNM-WT 1500012,13.

‘Ubeidya site locality. (a) Map of Africa and Eurasia with major Pleistocene paleoanthropological sites. Black circles denote sites with no osteological remains; red circles denote sites with human osteological remains. (b) The location of the site of ‘Ubeidiya, south of lake Kineret (Sea of Galilee), on the western banks of the Jordan Valley (red circle) (c) aerial photograph of the excavation plan of ‘Ubeidiya with the location of layer II-23 where UB 10749 was recovered.

In the Levant, the only site from this time-period with hominin remains is ‘Ubeidiya at the western escarpment of the Jordan Valley which is a part of the broader Rift Valley (Supplementary 1: Fig. 1b,c). The fossil remains include cranial fragments (UB 1703, 1704, 1705, and 1706), two incisor (UB 1700, UB 335) and a molar (UB 1701), identified as Homo cf. erectus/ergaster14,15,16,17,18. It is important to note that some of these fragments were bulldozed out of the ground preceding the first season, while others are considered intrusive and younger than the surroundings deposits17.

In 2018 during a reanalysis of the faunal assemblages done by two of the authors (A. B, and M. B.) a complete vertebral body (UB 10749) with hominin characteristics was found. This is the first hominin postcranial remain found at ‘Ubeidiya securely assigned to early Pleistocene deposits (See “Materials and methods”).

Here we assess the taxonomic affinity of UB 10749, its serial location along the spinal column, its chronological and physiological age at death, estimate the specimen's height and weight, and detect any pathological or taphonomic changes. Based on our findings, we explore the unique developmental characteristics of the UB 10749 within the context of early Homo paleobiology and its implications for hominin dispersal out of Africa.

No comments:

Post a Comment