Once upon a time, eager acolytes thought their false Messiah could make their country great again — sound familiar?

On the strange but insistent parallels between Sabbatai Sevi of Smyrna and Donald Trump of Queens

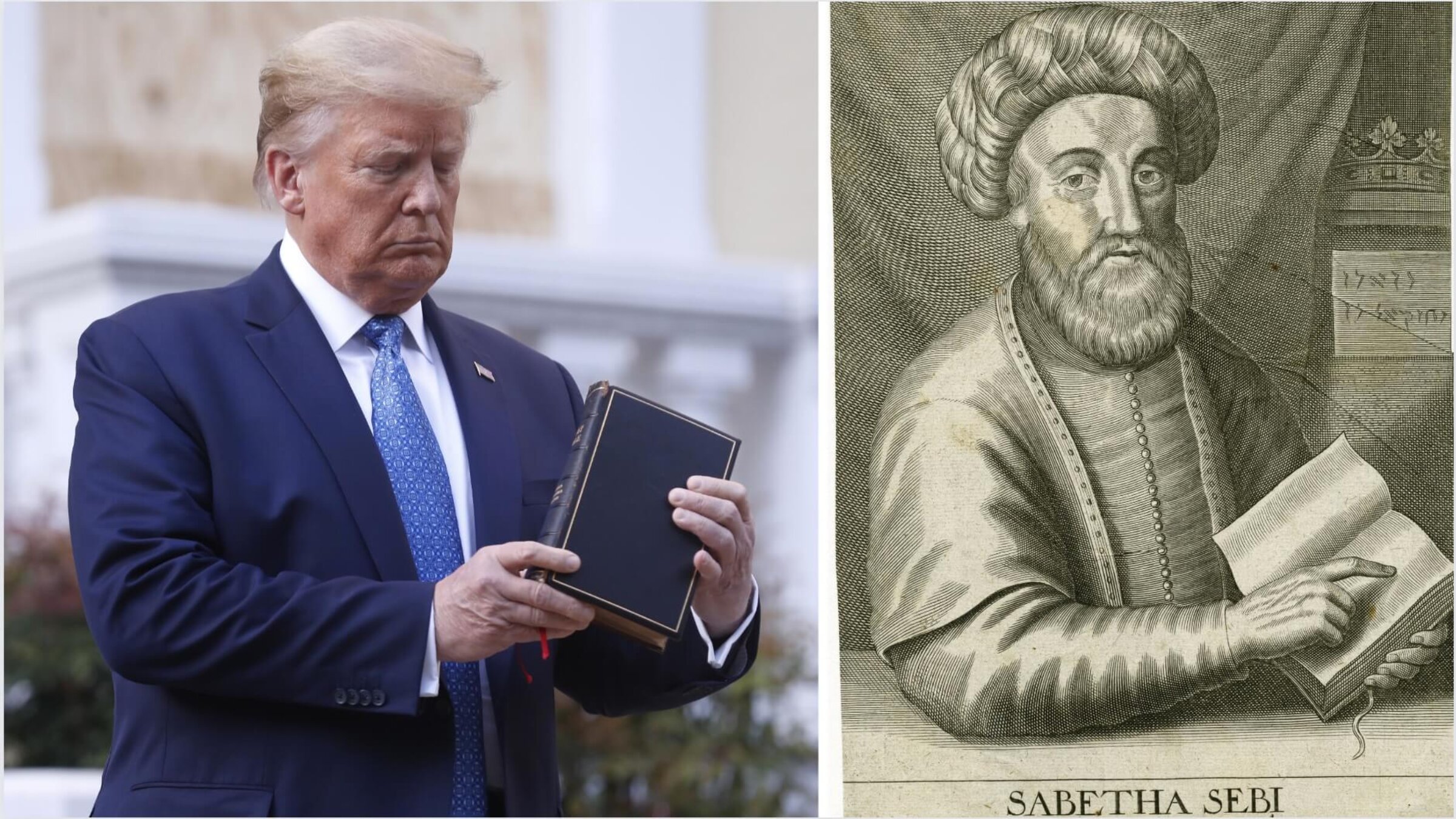

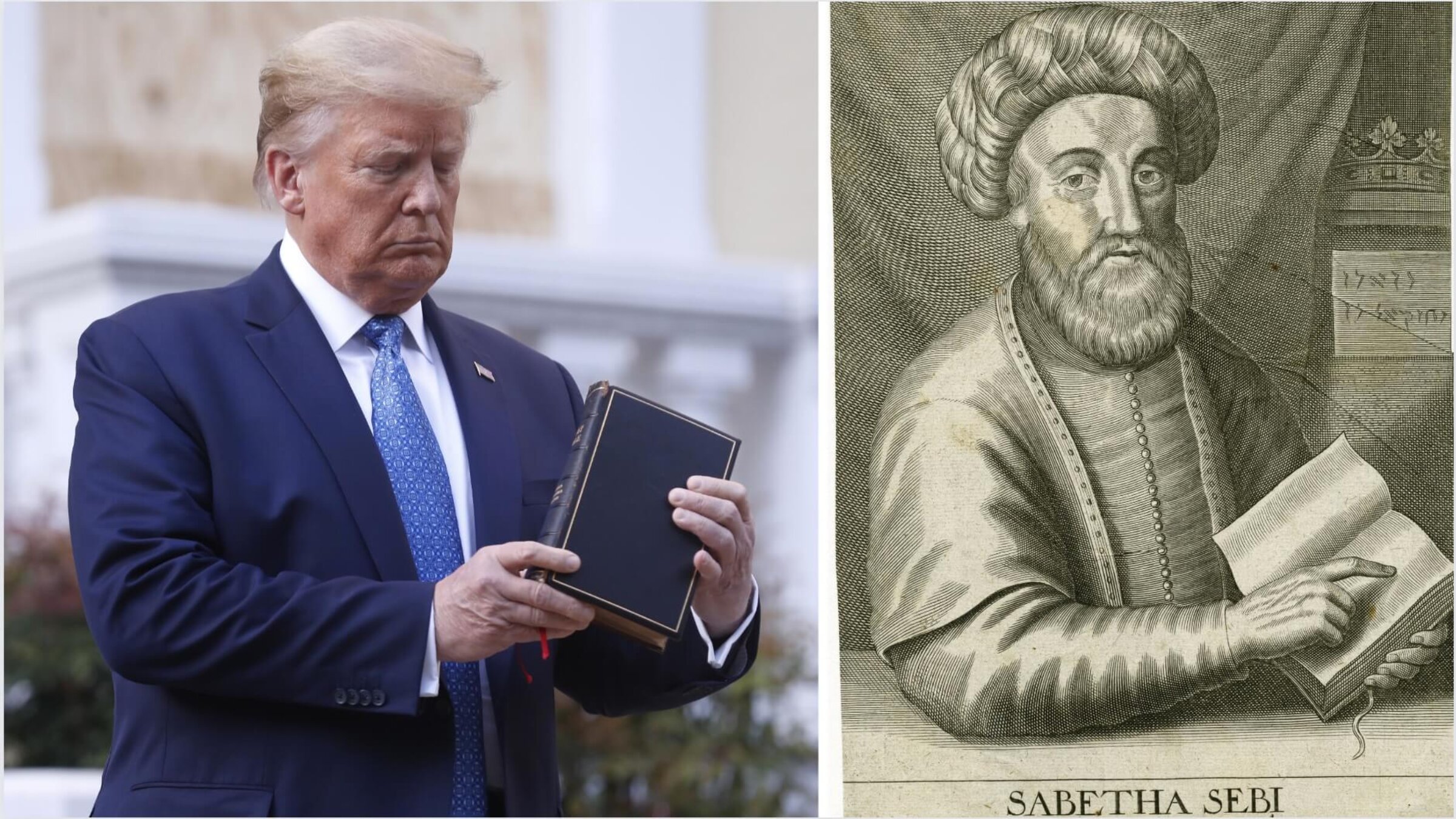

Donald Trump and Sabbatai Sevi — separated by centuries; joined by some common themes. Photo by Getty Images/Wikimedia Commons

By Robert Zaretsky

On the strange but insistent parallels between Sabbatai Sevi of Smyrna and Donald Trump of Queens

Donald Trump and Sabbatai Sevi — separated by centuries; joined by some common themes. Photo by Getty Images/Wikimedia Commons

By Robert Zaretsky

August 8, 2023

The Sabbatian movement, one of the most convulsive episodes in Jewish history, was launched 375 years ago. It is named after Sabbatai Sevi, a young native of Smyrna (present-day Izmir), who in 1648 announced that he was the Messiah. Sabbateanism, the movement hatched by this epiphany, ranks among the more striking examples of millenarianism, a worldview that anticipates the world’s end — tomorrow, if not today — when the forces of good and evil will meet in an apocalyptic clash, leading to a world of perfect peace and prosperity.

Sabbatai Sevi certainly had an eager audience for his claim. In some ways, 1648 was the best of times for European Jewry. The Treaty of Westphalia, which ended the Thirty Years’ War, created an independent Netherlands, which proceeded to become a haven of tolerance for Jews across the continent. In other ways, though, 1648 was the worst of times for European Jewry. Under the leadership of Bogdan Chmelnicki, the Cossacks, launching their war against their Polish rulers, torched and terrorized Jewish villages across the region. And it was also the strangest of times, thanks to this self-proclaimed Messiah from Smyrna whose credibility was strengthened by a Kabbalistic prediction that a Messiah would appear that very year.

Even stranger, perhaps, is that while Sabbatai Sevi died in 1676, as a convert to Islam, the apocalyptic worldview he represented remains with us to this very day. Nearly half a millennium after Sevi’s life and death, we are again living through a millenarian movement, one as apocalyptic as that of the Sabbatian movement.

A new Messiah

This, at least, is what a reader might take away from two of European Jewry’s most imaginative minds, Gershom Scholem and Isaac Bashevis Singer. It seems the two men never met, but both spent their lives exploring the world of Jewish mysticism. (When asked what made him Jewish, Allen Ginsberg cited his love of the “bohemian mysticism of Scholem and Singer.”) Singer and Scholem were both especially taken, observed the Yiddish scholar Ruth Wisse, “to the frenzy of the Sabbatian movement.” Such frenzy, both men also grasped, was not limited to a single place, time and people. Instead, it was a potential that resided in all of us, capable of erupting given the right conditions.

This awareness infuses Scholem’s magisterial work Sabbatai Sevi: The Mystical Messiah, 1626-1676, first published in Hebrew in 1957 and translated into English in 1973. (Re-issued as a Princeton Classic in 2016, it runs exactly 1000 pages, preceded by a critical and lucid introduction by Yaacob Dweck.) Though the title suggests a biography, the book is not really about Sabbatai Sevi, whom Scholem summarily diagnoses (and dismisses) as manic-depressive.

The Sabbatian movement, one of the most convulsive episodes in Jewish history, was launched 375 years ago. It is named after Sabbatai Sevi, a young native of Smyrna (present-day Izmir), who in 1648 announced that he was the Messiah. Sabbateanism, the movement hatched by this epiphany, ranks among the more striking examples of millenarianism, a worldview that anticipates the world’s end — tomorrow, if not today — when the forces of good and evil will meet in an apocalyptic clash, leading to a world of perfect peace and prosperity.

Sabbatai Sevi certainly had an eager audience for his claim. In some ways, 1648 was the best of times for European Jewry. The Treaty of Westphalia, which ended the Thirty Years’ War, created an independent Netherlands, which proceeded to become a haven of tolerance for Jews across the continent. In other ways, though, 1648 was the worst of times for European Jewry. Under the leadership of Bogdan Chmelnicki, the Cossacks, launching their war against their Polish rulers, torched and terrorized Jewish villages across the region. And it was also the strangest of times, thanks to this self-proclaimed Messiah from Smyrna whose credibility was strengthened by a Kabbalistic prediction that a Messiah would appear that very year.

Even stranger, perhaps, is that while Sabbatai Sevi died in 1676, as a convert to Islam, the apocalyptic worldview he represented remains with us to this very day. Nearly half a millennium after Sevi’s life and death, we are again living through a millenarian movement, one as apocalyptic as that of the Sabbatian movement.

A new Messiah

This, at least, is what a reader might take away from two of European Jewry’s most imaginative minds, Gershom Scholem and Isaac Bashevis Singer. It seems the two men never met, but both spent their lives exploring the world of Jewish mysticism. (When asked what made him Jewish, Allen Ginsberg cited his love of the “bohemian mysticism of Scholem and Singer.”) Singer and Scholem were both especially taken, observed the Yiddish scholar Ruth Wisse, “to the frenzy of the Sabbatian movement.” Such frenzy, both men also grasped, was not limited to a single place, time and people. Instead, it was a potential that resided in all of us, capable of erupting given the right conditions.

This awareness infuses Scholem’s magisterial work Sabbatai Sevi: The Mystical Messiah, 1626-1676, first published in Hebrew in 1957 and translated into English in 1973. (Re-issued as a Princeton Classic in 2016, it runs exactly 1000 pages, preceded by a critical and lucid introduction by Yaacob Dweck.) Though the title suggests a biography, the book is not really about Sabbatai Sevi, whom Scholem summarily diagnoses (and dismisses) as manic-depressive.

Gershom Scholem is the author of ‘Sabbatai Sevi: The Mystical Messiah.’ Photo by Wikimedia Commons

With a doctorate in history from the University of Munich, Scholem was the wrong sort of doctor to make such a diagnosis. Moreover, it was a diagnosis based on centuries-old contemporary accounts of Sevi.

Nevertheless, Scholem was the right sort of doctor to offer a historical account that portrays Sevi as almost accidental to the history of Sabbateanism. What was essential, Scholem argues, was the role played by Nathan of Gaza. In 1665, this young and gifted Kabbalist, who had shortly before prophesized the arrival of the Messiah, met Sevi during the latter’s ramblings across the Middle East. According to a key account, Nathan “fell to the ground before Sevi,” convinced that the man who had been mostly shunned or ignored by Jewish communities until then was indeed the Messiah.

The rest is the stuff of history, partly because Nathan shaped that history. He was at once, in Scholem’s words, “the John the Baptist and the Paul of the new Messiah.” Or, as we might now say, Nathan was the crisis manager for a Messiah who, when the sultan gave him the choice between death or conversion, plumped for the latter. Expecting redemption at any moment, the thousands of Jews who had flocked to Sevi were dumbfounded. Had they been sold a bill of soteriological goods?

To survive a leader’s act of apostasy, whether political or theological, a movement needs both a base filled with fanatical devotion and a front office led by a skilled spinmeister. More than up to the task, Nathan sought to reassure Sevi’s followers that the Kabbalist texts made clear the “necessity” of this apostasy. In short, Nathan warned them not to believe not just the Messiah’s many enemies, but what witnesses saw with their own eyes. For the faithful who hold fast to their leader, “they will taste celestial delights.” That they never did hardly dampened the enthusiasm of Sevi’s base; if anything, the fact that Sevi seemed to be a loser made his followers’ conviction that he was a winner all the stronger.

More than two decades before Scholem published his book, Singer had already anticipated his findings. In 1933, he published Satan in Goray in a Warsaw literary journal while still living in his native Poland. It is, Wisse believes, Singer’s best novel. Published the same year Hitler came to power in Germany and Stalin launched the famine in Ukraine, the novel is certainly Singer’s most prescient work.

It is also much shorter than Scholem’s. In barely 200 pages, Singer unfolds the story of Goray, a Jewish village ravaged by the Cossacks under Chmelnicki. “They slaughtered one very hand, flayed men alive, murdered small children, violated women and afterward ripped open their bellies and sewed cats inside.” When those who fled eventually returned, they buried the bones of those who had remained, but they could not bury the memory of what had happened.

With a doctorate in history from the University of Munich, Scholem was the wrong sort of doctor to make such a diagnosis. Moreover, it was a diagnosis based on centuries-old contemporary accounts of Sevi.

Nevertheless, Scholem was the right sort of doctor to offer a historical account that portrays Sevi as almost accidental to the history of Sabbateanism. What was essential, Scholem argues, was the role played by Nathan of Gaza. In 1665, this young and gifted Kabbalist, who had shortly before prophesized the arrival of the Messiah, met Sevi during the latter’s ramblings across the Middle East. According to a key account, Nathan “fell to the ground before Sevi,” convinced that the man who had been mostly shunned or ignored by Jewish communities until then was indeed the Messiah.

The rest is the stuff of history, partly because Nathan shaped that history. He was at once, in Scholem’s words, “the John the Baptist and the Paul of the new Messiah.” Or, as we might now say, Nathan was the crisis manager for a Messiah who, when the sultan gave him the choice between death or conversion, plumped for the latter. Expecting redemption at any moment, the thousands of Jews who had flocked to Sevi were dumbfounded. Had they been sold a bill of soteriological goods?

To survive a leader’s act of apostasy, whether political or theological, a movement needs both a base filled with fanatical devotion and a front office led by a skilled spinmeister. More than up to the task, Nathan sought to reassure Sevi’s followers that the Kabbalist texts made clear the “necessity” of this apostasy. In short, Nathan warned them not to believe not just the Messiah’s many enemies, but what witnesses saw with their own eyes. For the faithful who hold fast to their leader, “they will taste celestial delights.” That they never did hardly dampened the enthusiasm of Sevi’s base; if anything, the fact that Sevi seemed to be a loser made his followers’ conviction that he was a winner all the stronger.

More than two decades before Scholem published his book, Singer had already anticipated his findings. In 1933, he published Satan in Goray in a Warsaw literary journal while still living in his native Poland. It is, Wisse believes, Singer’s best novel. Published the same year Hitler came to power in Germany and Stalin launched the famine in Ukraine, the novel is certainly Singer’s most prescient work.

It is also much shorter than Scholem’s. In barely 200 pages, Singer unfolds the story of Goray, a Jewish village ravaged by the Cossacks under Chmelnicki. “They slaughtered one very hand, flayed men alive, murdered small children, violated women and afterward ripped open their bellies and sewed cats inside.” When those who fled eventually returned, they buried the bones of those who had remained, but they could not bury the memory of what had happened.

In Satan in Goray, Isaac Bashevis Singer, pictured here in 1968 outside the Forward Building, depicted a land gripped by Messianic fervor.

Photo by Getty Images

The massacres, the narrator drily notes, “were the birth-pangs of the Messiah.” The survivors of Goray are left wide open to a second invasion, one advertised in the Messianic message carried by the followers of Sevi. Blazing like a deadly pathogen through a vulnerable population, tales of miraculous events, each portending Messianic redemption, crackled through the shtetls and ghettos across the continent. These mysterious occurrences all led back to Sabbatai Sevi, a maker of miracles who, as one visitor to Goray affirms, “was as tall as a cedar” and whose face was too brilliant to behold.

The tidal wave of Messianic fervor washing over Goray, a devastated place desperate for hope, sweeps away those who, like Rabbi Benish, refuse to surrender their reason. What follows, depicted by Singer in crisp, nearly clinical language, is petrifying. Certain that redemption was around the corner, the villagers indulge in every imaginable excess, turning Goray into a place where any and all kinds of behavior, whether in the bedroom or the synagogue, was not just permitted, but expected.

Once news of Sevi’s apostasy reaches Goray, the depths of human behavior are fully plumbed. As factions arise between those who know Sevi is pulling the wool over the sultan’s eyes and those who know Sevi has pulled the wool over their own eyes, Goray slips into civil war. Moreover, there are differences even within the first camp, with one group concluding that if they are to be redeemed, they must first test the outermost limits of evil. They outdid one another in ways to desecrate the Sabbath, from practicing serial acts of adultery to the practice of adulterating kosher meat.

What Singer and Scholem understood about us

For both Singer and Scholem, Jewish mysticism is clearly so much more than a bohemian tendency. It was too enticing to take wonders in the writings of Isaac Luria, the founder of modern Kabbalah, and transform them into a howl against the way things had been for an entire people since time immemorial. Hence the promise of Lurianic mysticism, for it contains the promise of making the world whole again. But it also contains the potential of unmaking the world entirely. While Scholem warned against making any comparisons between events in the 17th and 20th centuries, he nevertheless did so toward the end of his life.

In an interview in 1980 with the historian David Biale, Scholem declared that the very same apocalyptic fervor that defined the Sabbatian movement also fired the Messianism of the Jewish settler movement.

As for Singer, historical events come and go, but human nature stays the same. In her introduction to Satan in Goray, Wisse quotes Singer’s recollection about arguments he had with his brother Israel over the idea of human progress. Always the optimist, Israel believed that “little by little, humankind would learn from its mistakes. My brother needed this faith in moral progress, although the facts refuted him left and right.”

His task, he then believed, was to “mercilessly destroy his humanistic illusions.” It was only years later, Singer concludes, that he came to regret his destruction of Israel’s beliefs, if only because he had nothing with which to replace them.

Despite Scholem’s warning, it is hard to ignore the many parallels we can draw between now and then. Just as Scholem, perhaps mistakenly, puts Sevi on the couch (and then in a straitjacket), we have done, perhaps no less mistakenly, with Donald Trump. While his followers vaunt him as the Messiah who will fix our country, too many specialists and non-specialists have put him on the couch (and then, it is hoped, in a prison cell).

Or, again, just as Nathan of Gaza devoted his life to putting Sevi’s outrageous acts and words into the proper Kabbalist context, Tucker of Fox, along with others, has devoted a career to putting Trump’s vile remarks in their proper context. Or, finally, just as Sevi’s apostasy reinforced the attachment of his followers — only a seeming paradox, since the psychic cost of admitting the truth was too great — so too with the support of Trump’s base, which deepens with each new indictment.

But these parallels either go only so far or not nearly far enough. They miss what both Scholem and Singer understood about us. As the narrator of Singer’s story concludes, “Goray, that small town at the edge of the world, was altered. No one recognized it any longer.” Perhaps we can say the same of our world today. But the funny thing is that, for those who try to keep their eyes open, they will always recognize the world for what it always, and unchangingly, was.

The massacres, the narrator drily notes, “were the birth-pangs of the Messiah.” The survivors of Goray are left wide open to a second invasion, one advertised in the Messianic message carried by the followers of Sevi. Blazing like a deadly pathogen through a vulnerable population, tales of miraculous events, each portending Messianic redemption, crackled through the shtetls and ghettos across the continent. These mysterious occurrences all led back to Sabbatai Sevi, a maker of miracles who, as one visitor to Goray affirms, “was as tall as a cedar” and whose face was too brilliant to behold.

The tidal wave of Messianic fervor washing over Goray, a devastated place desperate for hope, sweeps away those who, like Rabbi Benish, refuse to surrender their reason. What follows, depicted by Singer in crisp, nearly clinical language, is petrifying. Certain that redemption was around the corner, the villagers indulge in every imaginable excess, turning Goray into a place where any and all kinds of behavior, whether in the bedroom or the synagogue, was not just permitted, but expected.

Once news of Sevi’s apostasy reaches Goray, the depths of human behavior are fully plumbed. As factions arise between those who know Sevi is pulling the wool over the sultan’s eyes and those who know Sevi has pulled the wool over their own eyes, Goray slips into civil war. Moreover, there are differences even within the first camp, with one group concluding that if they are to be redeemed, they must first test the outermost limits of evil. They outdid one another in ways to desecrate the Sabbath, from practicing serial acts of adultery to the practice of adulterating kosher meat.

What Singer and Scholem understood about us

For both Singer and Scholem, Jewish mysticism is clearly so much more than a bohemian tendency. It was too enticing to take wonders in the writings of Isaac Luria, the founder of modern Kabbalah, and transform them into a howl against the way things had been for an entire people since time immemorial. Hence the promise of Lurianic mysticism, for it contains the promise of making the world whole again. But it also contains the potential of unmaking the world entirely. While Scholem warned against making any comparisons between events in the 17th and 20th centuries, he nevertheless did so toward the end of his life.

In an interview in 1980 with the historian David Biale, Scholem declared that the very same apocalyptic fervor that defined the Sabbatian movement also fired the Messianism of the Jewish settler movement.

As for Singer, historical events come and go, but human nature stays the same. In her introduction to Satan in Goray, Wisse quotes Singer’s recollection about arguments he had with his brother Israel over the idea of human progress. Always the optimist, Israel believed that “little by little, humankind would learn from its mistakes. My brother needed this faith in moral progress, although the facts refuted him left and right.”

His task, he then believed, was to “mercilessly destroy his humanistic illusions.” It was only years later, Singer concludes, that he came to regret his destruction of Israel’s beliefs, if only because he had nothing with which to replace them.

Despite Scholem’s warning, it is hard to ignore the many parallels we can draw between now and then. Just as Scholem, perhaps mistakenly, puts Sevi on the couch (and then in a straitjacket), we have done, perhaps no less mistakenly, with Donald Trump. While his followers vaunt him as the Messiah who will fix our country, too many specialists and non-specialists have put him on the couch (and then, it is hoped, in a prison cell).

Or, again, just as Nathan of Gaza devoted his life to putting Sevi’s outrageous acts and words into the proper Kabbalist context, Tucker of Fox, along with others, has devoted a career to putting Trump’s vile remarks in their proper context. Or, finally, just as Sevi’s apostasy reinforced the attachment of his followers — only a seeming paradox, since the psychic cost of admitting the truth was too great — so too with the support of Trump’s base, which deepens with each new indictment.

But these parallels either go only so far or not nearly far enough. They miss what both Scholem and Singer understood about us. As the narrator of Singer’s story concludes, “Goray, that small town at the edge of the world, was altered. No one recognized it any longer.” Perhaps we can say the same of our world today. But the funny thing is that, for those who try to keep their eyes open, they will always recognize the world for what it always, and unchangingly, was.

A professor at the University of Houston, Robert Zaretsky is also a culture columnist at the Forward. He is now writing a book on Stendhal and the art of living

SEE

No comments:

Post a Comment