Written byYunnan Chen, Andrew Herscowitz

ODI | ODI: Think change

04 April 2024

Haikou Xiuying Port Container Terminal.

Image license:DreamArchitect/Shutterstock

The Belt and Road Forum in October 2023 marked a decade of China’s flagship initiative, revitalising the rhetoric of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) following years of negative PR. It was a political signal that President Xi Jinping’s initiative was not going away. The forum also signalled a shift in the next phase of BRI in terms of China’s overseas finance, in a much leaner and more targeted direction, but also with a much more conservative risk appetite. With respect to both past Chinese investments and the future trajectory of Chinese investments, one financial institution has been critical to China’s management of its overseas risk: Sinosure.

A recent ODI report, Hedging Belts, De-risking Road: Sinosure in China’s overseas finance and the evolving international response, shines a light on Sinosure, China’s other export credit agency (ECA), whose less-profiled role in overseas finance has to date been little understood.

This is the first instalment of the three-part series, 'China’s overseas finance in the era of competition', that explores the rise of – and responses to – China’s distinct model of overseas finance. It examines the critical role of Sinosure in de-risking overseas lending and enabling this overseas finance at scale, with updated figures on its financing trends. A second ODI Insight will dive into the international responses to China’s influence on export credit and development finance, looking at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) institutions and European actors. A final piece offers the perspective from the United States (US), underscoring policy implications for the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) in the context of intensifying bilateral competition.

What does Sinosure do?

Unlike the Export–Import Bank of China (Eximbank), the policy bank that has been the most active in low- and middle-income countries, Sinosure’s role is not that of a lender but a policy insurer. Analogous to the World Bank Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) and many other export credit agencies, Sinosure specialises in guarantees and insurance covering political and commercial risk. Sinosure began largely with a trade-based mandate of promoting Chinese goods and services. But its role expanded dramatically following a major capital injection in 2011 from China’s sovereign wealth fund, to increasingly support not only the export of Chinese goods but also Chinese capital, via overseas investment and overseas lending.

In the promotion of the BRI, Sinosure has played a massive, critical role. According to its annual reports, by the end of 2022, Sinosure had provided over $1.3 trillion of insurance over projects in BRI countries. BRI-country activities in support of exports, financing and investment have constituted an estimated one-quarter of Sinosure’s total insurance activities over this period.

Insuring the BRI and overseas lending

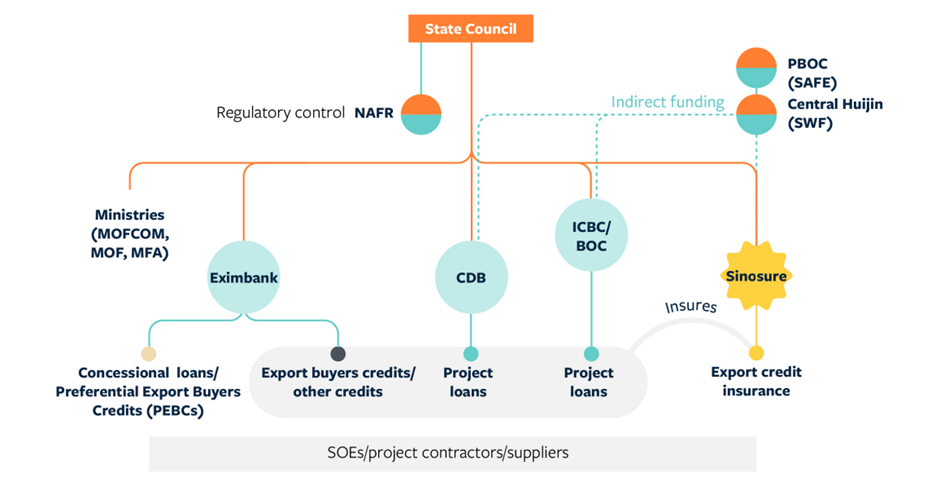

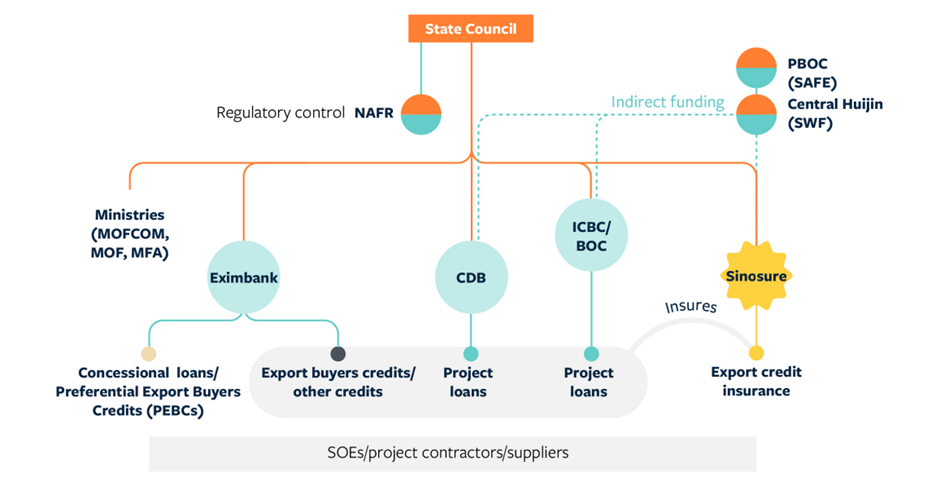

Perhaps most intriguing has been Sinosure’s role in guaranteeing China’s overseas lending, which has been a key – and controversial – feature of China’s BRI. Sinosure doesn’t cover all lending, but it can cover significant portions of policy bank lending from China Eximbank and the China Development Bank (CDB; Figure 1), as well as commercial bank loans, taking on the higher-value projects of Eximbank’s portfolio and allowing Eximbank to expand its lending capacity and take on more risk. Meanwhile, for state-owned commercial banks, which have a lower risk tolerance in high-risk countries, Sinosure guarantees are seen as practically essential for them to be willing to finance.

Image credit:Figure 1: Sinosure’s insurance is eligible for most commercial loans from policy banks and state-owned commercial banks

This de-risking function has been instrumental in expanding the risk appetite of Chinese commercial lending, mobilising a significant layer of overseas financing. Sinosure has been critical in underwriting some of the largest infrastructure projects under BRI, including the Maputo–Katembe suspension bridge in Mozambique; the flagship standard gauge railways in Kenya and Ethiopia; and multiple projects under the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), among many others. Estimates based on figures from AidData up to 2021 indicate that around $230 billion – at least 12% – of China’s overseas lending from 2000–2021 was enabled through Sinosure coverage.

Once bitten, twice shy

However, this function has also generated clear moral hazards in China’s overseas lending. Policy banks, commercial banks and Sinosure are mandated to support the promotion of Chinese goods, services and technologies. Much of this has been enabled by the small portfolio of medium- to long-term (MLT) insurance (Figure 2), which typically covers 95% of the project value. This means Sinosure bears nearly all the default risk, but with limited capacity to influence or refuse projects considered strategic. Meanwhile, Chinese state-owned enterprise contractors, who often help broker projects with host governments, bear little of the risk if governments default down the line.

A Flourish data visualization

A Flourish data visualization

Figure 2: Sinosure’s portfolio activities 2014–2022. Source: Sinosure annual reports 2019, 2021, 2022

Once burned, Sinosure learned. The squeeze in MLT coverage after 2018 (Figure 2) coincides with several restructurings in this period, where it made payouts on significant BRI project loans. The subsequent decrease in risk appetite mirrors the broader, well-noted decline in overseas lending, indicating that the shrinking in Sinosure’s risk appetite contributed to the broader pullback in lending from Chinese banks. Remarkably, other instruments such as overseas investment insurance and domestic trade credit insurance have not decreased; instead, the latter has grown to buffer Chinese exporters from the impacts of the US–China trade war.

But Sinosure’s appetite, and capacity, for risk has dropped. Recently, Sinosure has taken the step of cutting back its risk coverage provision in countries that have previously defaulted or are in arrears. Even in Pakistan, one of the biggest BRI partners, Sinosure has reduced its coverage capacity for the country from 95% to 70%, in response to Pakistan’s fiscal issues and payment delays. While not refusing new projects outright, this pullback essentially reflects a soft veto, forcing banks, contractors and project owners to either seek additional coverage elsewhere, or to share more of the financial risk. The next decade of the BRI 2.0 will not see the same exuberance of lending as the last – and creditors will be much stingier.

Sinosure in debt restructuring

Debt sustainability has also become a live issue that has pushed Sinosure into the limelight, as part of China’s participation in the G20 Common Framework. In theory, in the event of default, Sinosure has subrogation rights, giving it the legal authority to renegotiate across all Chinese creditors, and having the final approval over any restructured loans. But despite its cross-institutional role and vantage point across multiple Chinese creditors, Sinosure’s participation in debt restructurings has been curiously muted. Instead, it has taken a backseat to China Eximbank, which has acted as lead representative for all Chinese official creditors.

Even so, Sinosure has exerted influence over debt norms: in Zambia, Sinosure, with Eximbank, pushed back on the inclusion of Sinosure-guaranteed loans as ‘official’ loans despite their state-guarantee – breaking with the Paris Club norm for ECA-guaranteed debt. This likely comes from resistance to extending the eligible portfolio of debt for restructuring – Boston University GDP Center estimates an additional $4.1 billion of CDB loans for Zambia would have been then classified as ‘official’ debt for restructuring. But this choice has come with a trade-off; as Brad Setser and Theo Maret argue, Chinese commercial creditors are now disadvantaged relative to faster-moving bondholders in the process, further complicating the comparability-of-treatment issue, and deepening Zambia’s debt woes.

De-risking the next decade of the BRI

One thing is clear: the second decade of the BRI will not replicate the first. Sinosure guarantees have been a huge part of the BRI in the last decade, and a significant instrument in enabling Chinese banks in overseas lending. This era is over, and Sinosure’s diminished appetite and capacity for risk – and China’s own domestic economic headwinds – are likely to squeeze the capacity of banks and investors going forward.

Even with tightened constraints, Sinosure’s scale remains massive. Plans to overhaul MIGA’s provision of guarantees pledges to triple issuances to $20 billion by 2030 – compare this to Sinosure’s $70 billion of overseas investment insurance in 2022 alone (Figure 2). If the World Bank seeks to compete, it will need to seriously raise its ambitions in scale.

One big shift will be the sector focus. As China scales up clean energy development at home to meet its carbon neutrality and energy transition goals, it will be its clean tech sectors – renewables rather than railways – that ‘go out’ in the years to come. Sinosure, whose new motto of ‘small yet smart’ (echoing the official BRI motto of ‘small and beautiful’) is quickly ramping up its insurance of green and renewable projects and supporting green finance, as well as new expanding in the medical and health fields.

This is likely to be the new frontier of competition, as our next blog will discuss. The rise and scale of China’s official lending and guarantees have put huge pressure on the existing norms and frameworks that govern aid and industrial competition. This great power competition will have potentially unanticipated consequences for OECD rules themselves, as new reforms seek to level the playing field.

Many thanks to Frederique Dahan and Mark Miller for their feedback and comments, and to Zoe Zongyuan Liu for her inputs.

The Belt and Road Forum in October 2023 marked a decade of China’s flagship initiative, revitalising the rhetoric of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) following years of negative PR. It was a political signal that President Xi Jinping’s initiative was not going away. The forum also signalled a shift in the next phase of BRI in terms of China’s overseas finance, in a much leaner and more targeted direction, but also with a much more conservative risk appetite. With respect to both past Chinese investments and the future trajectory of Chinese investments, one financial institution has been critical to China’s management of its overseas risk: Sinosure.

A recent ODI report, Hedging Belts, De-risking Road: Sinosure in China’s overseas finance and the evolving international response, shines a light on Sinosure, China’s other export credit agency (ECA), whose less-profiled role in overseas finance has to date been little understood.

This is the first instalment of the three-part series, 'China’s overseas finance in the era of competition', that explores the rise of – and responses to – China’s distinct model of overseas finance. It examines the critical role of Sinosure in de-risking overseas lending and enabling this overseas finance at scale, with updated figures on its financing trends. A second ODI Insight will dive into the international responses to China’s influence on export credit and development finance, looking at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) institutions and European actors. A final piece offers the perspective from the United States (US), underscoring policy implications for the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) in the context of intensifying bilateral competition.

What does Sinosure do?

Unlike the Export–Import Bank of China (Eximbank), the policy bank that has been the most active in low- and middle-income countries, Sinosure’s role is not that of a lender but a policy insurer. Analogous to the World Bank Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) and many other export credit agencies, Sinosure specialises in guarantees and insurance covering political and commercial risk. Sinosure began largely with a trade-based mandate of promoting Chinese goods and services. But its role expanded dramatically following a major capital injection in 2011 from China’s sovereign wealth fund, to increasingly support not only the export of Chinese goods but also Chinese capital, via overseas investment and overseas lending.

In the promotion of the BRI, Sinosure has played a massive, critical role. According to its annual reports, by the end of 2022, Sinosure had provided over $1.3 trillion of insurance over projects in BRI countries. BRI-country activities in support of exports, financing and investment have constituted an estimated one-quarter of Sinosure’s total insurance activities over this period.

Insuring the BRI and overseas lending

Perhaps most intriguing has been Sinosure’s role in guaranteeing China’s overseas lending, which has been a key – and controversial – feature of China’s BRI. Sinosure doesn’t cover all lending, but it can cover significant portions of policy bank lending from China Eximbank and the China Development Bank (CDB; Figure 1), as well as commercial bank loans, taking on the higher-value projects of Eximbank’s portfolio and allowing Eximbank to expand its lending capacity and take on more risk. Meanwhile, for state-owned commercial banks, which have a lower risk tolerance in high-risk countries, Sinosure guarantees are seen as practically essential for them to be willing to finance.

Image credit:Figure 1: Sinosure’s insurance is eligible for most commercial loans from policy banks and state-owned commercial banks

This de-risking function has been instrumental in expanding the risk appetite of Chinese commercial lending, mobilising a significant layer of overseas financing. Sinosure has been critical in underwriting some of the largest infrastructure projects under BRI, including the Maputo–Katembe suspension bridge in Mozambique; the flagship standard gauge railways in Kenya and Ethiopia; and multiple projects under the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), among many others. Estimates based on figures from AidData up to 2021 indicate that around $230 billion – at least 12% – of China’s overseas lending from 2000–2021 was enabled through Sinosure coverage.

Once bitten, twice shy

However, this function has also generated clear moral hazards in China’s overseas lending. Policy banks, commercial banks and Sinosure are mandated to support the promotion of Chinese goods, services and technologies. Much of this has been enabled by the small portfolio of medium- to long-term (MLT) insurance (Figure 2), which typically covers 95% of the project value. This means Sinosure bears nearly all the default risk, but with limited capacity to influence or refuse projects considered strategic. Meanwhile, Chinese state-owned enterprise contractors, who often help broker projects with host governments, bear little of the risk if governments default down the line.

Figure 2: Sinosure’s portfolio activities 2014–2022. Source: Sinosure annual reports 2019, 2021, 2022

Once burned, Sinosure learned. The squeeze in MLT coverage after 2018 (Figure 2) coincides with several restructurings in this period, where it made payouts on significant BRI project loans. The subsequent decrease in risk appetite mirrors the broader, well-noted decline in overseas lending, indicating that the shrinking in Sinosure’s risk appetite contributed to the broader pullback in lending from Chinese banks. Remarkably, other instruments such as overseas investment insurance and domestic trade credit insurance have not decreased; instead, the latter has grown to buffer Chinese exporters from the impacts of the US–China trade war.

But Sinosure’s appetite, and capacity, for risk has dropped. Recently, Sinosure has taken the step of cutting back its risk coverage provision in countries that have previously defaulted or are in arrears. Even in Pakistan, one of the biggest BRI partners, Sinosure has reduced its coverage capacity for the country from 95% to 70%, in response to Pakistan’s fiscal issues and payment delays. While not refusing new projects outright, this pullback essentially reflects a soft veto, forcing banks, contractors and project owners to either seek additional coverage elsewhere, or to share more of the financial risk. The next decade of the BRI 2.0 will not see the same exuberance of lending as the last – and creditors will be much stingier.

Sinosure in debt restructuring

Debt sustainability has also become a live issue that has pushed Sinosure into the limelight, as part of China’s participation in the G20 Common Framework. In theory, in the event of default, Sinosure has subrogation rights, giving it the legal authority to renegotiate across all Chinese creditors, and having the final approval over any restructured loans. But despite its cross-institutional role and vantage point across multiple Chinese creditors, Sinosure’s participation in debt restructurings has been curiously muted. Instead, it has taken a backseat to China Eximbank, which has acted as lead representative for all Chinese official creditors.

Even so, Sinosure has exerted influence over debt norms: in Zambia, Sinosure, with Eximbank, pushed back on the inclusion of Sinosure-guaranteed loans as ‘official’ loans despite their state-guarantee – breaking with the Paris Club norm for ECA-guaranteed debt. This likely comes from resistance to extending the eligible portfolio of debt for restructuring – Boston University GDP Center estimates an additional $4.1 billion of CDB loans for Zambia would have been then classified as ‘official’ debt for restructuring. But this choice has come with a trade-off; as Brad Setser and Theo Maret argue, Chinese commercial creditors are now disadvantaged relative to faster-moving bondholders in the process, further complicating the comparability-of-treatment issue, and deepening Zambia’s debt woes.

De-risking the next decade of the BRI

One thing is clear: the second decade of the BRI will not replicate the first. Sinosure guarantees have been a huge part of the BRI in the last decade, and a significant instrument in enabling Chinese banks in overseas lending. This era is over, and Sinosure’s diminished appetite and capacity for risk – and China’s own domestic economic headwinds – are likely to squeeze the capacity of banks and investors going forward.

Even with tightened constraints, Sinosure’s scale remains massive. Plans to overhaul MIGA’s provision of guarantees pledges to triple issuances to $20 billion by 2030 – compare this to Sinosure’s $70 billion of overseas investment insurance in 2022 alone (Figure 2). If the World Bank seeks to compete, it will need to seriously raise its ambitions in scale.

One big shift will be the sector focus. As China scales up clean energy development at home to meet its carbon neutrality and energy transition goals, it will be its clean tech sectors – renewables rather than railways – that ‘go out’ in the years to come. Sinosure, whose new motto of ‘small yet smart’ (echoing the official BRI motto of ‘small and beautiful’) is quickly ramping up its insurance of green and renewable projects and supporting green finance, as well as new expanding in the medical and health fields.

This is likely to be the new frontier of competition, as our next blog will discuss. The rise and scale of China’s official lending and guarantees have put huge pressure on the existing norms and frameworks that govern aid and industrial competition. This great power competition will have potentially unanticipated consequences for OECD rules themselves, as new reforms seek to level the playing field.

Many thanks to Frederique Dahan and Mark Miller for their feedback and comments, and to Zoe Zongyuan Liu for her inputs.

No comments:

Post a Comment