The Biggest Crane Barge on the Baltimore Bridge Project Has a CIA Past

The largest crane barge on the U.S. East Coast has arrived in Baltimore to help remove the wreckage of the Francis Scott Key Bridge - and its past may come as a surprise.

The Chesapeake 1000 (ex name Sun 800) is a floating derrick with a capacity of 1,000 short tons. The venerable crane barge was built at Sun Shipbuilding in 1972, the same year as the famed CIA spy ship Glomar Explorer. This was not a coincidence: the barge was constructed by Sun Ship for use in its own yard, specifically for installing super-heavy components for the Glomar Explorer project.

The Glomar Explorer was one of the most remarkable covert projects of the Cold War era, with a cover story worthy of a spy novel. In the early 1970s, the CIA decided to build a ship that could retrieve a lost Soviet ballistic missile submarine from the seafloor off Hawaii. This unique ship would have a massive grab claw, which would scoop the submarine up and retrieve it (hopefully) in one piece.

In order to make sure that Moscow didn't learn of this plan, CIA leaders asked reclusive billionaire Howard Hughes to help out with a pretext for the operation. The future Glomar Explorer would be billed to the press as a Hughes-led expedition to prospect for deep-sea minerals in the Pacific - the first deep-sea mining project of its kind. Even Sun Shipbuilding, which won the contract for construction, did not appear to be in on the real mission.

When the real story leaked out in 1975, government sources told journalists that the mission was a partial success: Glomar Explorer arrived on site, deployed its claw, and retrieved the forward third of the submarine. The true mission objectives - the sub's code books and missiles - were lost when the other two-thirds of the sub slipped back down to the bottom.

The Sun 800 wasn't along for this deep-sea mission, but played an essential role in making it happen. The heavy derrick barge lifted the Glomar Explorer's 630-ton gimbal onto the ship during construction. (The vessel had a fully-gimbaled, heave-compensated derrick platform designed to damp out ship motion in the swells of the open Pacific.)

After the project, Sun Shipbuilding kept the Sun 800 on hand for other yard work, as well as marine construction and civil engineering projects. It was eventually sold on to another shipyard, then to salvor Donjon Marine, which operates it today as the Chesapeake 1000. It is expected to play a high-profile role in removing the wrecked bridge truss from the bow of the boxship Dali, which is currently pinned in place by the weight of the span.

For more on the infamous Glomar Explorer, be sure to read The Maritime Executive's two-part history of the project: https://maritime-executive.com/features/grand-finale-for-infamous-glomar-explorer

Salvage Operation Focuses on Temporary Channels for Baltimore Harbor

The U.S. Coast Guard leading the Unified Command and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers are focusing on the opening of temporary alternative channels as they respond to the bridge collapse in Baltimore. They outlined the phased approach highlighting that they expect to open three successively larger channels to begin to resume some ship movements in Baltimore Harbor.

The first of the three channels is planned for the north side and teams from the command were already seen yesterday, March 31, placing the first buoys in the water around the debris from the Francis Scott Key Bridge. Officials were hoping to open the channel today, April 1, noting that it will be in place quickly for smaller, essential vessels.

The first temporary channel, however, will just have a depth of 11 feet limiting the vessels that will be able to use it. It will have a 264-foot horizontal clearance and a vertical clearance of 96 feet. Officially are describing its use for response vessels and those participating in the salvage operation.

“This will mark an important first step along the road to reopening the port of Baltimore,” said Capt. David O’Connell, Federal On-Scene Coordinator, Key Bridge Response 2024. “By opening this alternate route, we will support the flow of marine traffic into Baltimore.”

USCG teams began placing markers on Sunday for the first temporary channel (Unified Command)

Within a few days, they also expect to add a second channel Captain O’Connell described during an interview with CBS News. He said that some of the debris will have to be cleared first but they would then add a channel to the south with a depth of about 14 feet. He called it a start in the plans to restore vessel movement saying it should be able to accommodate some smaller tugs.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers outlined the phases saying that they are focusing on clearing the federal channel. To achieve this, they are working on establishing a consolidation point for the wreckage. They will also focus on removing the roadway and bridge span on the bow of the Dali.

O’Connell told CBS News this would permit them to open a third channel with a depth of 20 to 25 feet. He said that was in the works saying it would permit “a lot more commercial vessels,” to resume sailing into and out of Baltimore harbor.

The Army Corps said they were also focusing on objectives to stabilize the Dali and analyze the internal bridge truss structure. On Sunday, in addition to the cutting teams working on the north side of the collapsed bridge truss, three dive teams were surveying sections of the bridge and the Dali. The Army Corps wants to prevent the ship from pivoting and then prepare for the removal first of the bridge structure and then damaged or destabilized containers as necessary.

As the work progresses, they said they would position assets for repositioning and then refloating the Dali. In the second phase, they look to remove the ship before the final phase which will complete clearing all the wreckage.

Demolition Contractors Remove First Piece of Baltimore Bridge's Wreckage

On Saturday, contractors for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began removing the first piece of the wrecked Francis Scott Key Bridge, launching a carefully-planned process to clear a channel and reopen the Port of Baltimore. The work will proceed around the clock, Maryland Gov. Wes Moore said at a press conference Saturday.

The demolition teams are beginning work to the north of the main span, and their first task will be to open up an auxiliary shallow-draft channel.

"We'll continue planning efforts for once we open that up for tug and barge traffic to come into the Port of Baltimore," said Coast Guard 5th District Commander Rear Adm. Shannon Gilreath at a press conference Saturday. "Even if it's not the deep draft [channel], we want to take advantage of that opportunity."

After the debris is cleared, the auxiliary channel will be carefully surveyed to determine draft restrictions. The Coast Guard will place buoys to outline the safe fairway for tug operators. Traffic may be subject to restrictions in order to ensure that it does not interfere with the work to clear the rest of the bridge, Gilreath said.

As predicted by many shipping analysts, other East Coast ports are absorbing Baltimore's containerized cargo without much difficulty, Virginia Port Authority's Steve Edwards told CBS. "I think the economic shock is local," he said. "It's not across the region, and it's not across the nation." Port of Baltimore is on many of the same service strings as the much larger Port of New York and New Jersey and the Port of Virginia, so Baltimore-bound boxes can be offloaded at earlier or later port calls and then trucked to their final destinations. With the late-pandemic import boom long over, other East Coast ports have spare capacity to accept extra cargo.

The alternative arrangements for offloading ro/ro cargo - cars and rolling equipment - are less clear; Baltimore leads the nation in these cargo categories, and only one of its ro/ro terminals is still functioning. "This is the No. 1 auto port in the entire United States, so there will absolutely be some disruption when you have both import and export vehicles. But we don't know the extent of disruption because companies are working on ways to reroute things," said Alliance for Automotive Innovation CEO John Bozzella.

In the meantime, Port of Baltimore's land-side operations remain open, and longshore workers continue to send import cargo out the gates for final-mile delivery. The port is also exploring other opportunities to bring longshoremen back to work until shipping resumes.

As the bridge is dismantled, the wreckage will be transported to a scrapping site at nearby Tradepoint Atlantic, Dredging Contractors of America CEO Bill Doyle told The Maritime Executive. He could not give an exact timeline for the work's completion, but said that it would be faster than many observers might think, thanks to an abundance of available private-sector resources.

Workers at the bridge site have two barge cranes on scene to assist, one rated at 650 tons and one at 330 tons. The East Coast's heaviest crane barge, the Chesapeake 1,000, is standing by to assist when needed. In addition to the resources of the Army Corps of Engineers and its contractors, the U.S. Navy's Supervisor of Diving and Salvage has chartered additional barges to carry wreckage and is mobilizing 12 support vessels to Baltimore, according to Navy Times.

In Baltimore, Ship Strike "Never Occurred to Anybody"; In Delaware, It Did

Two former Maryland transport officials told the Washington Post that the state didn't consider the risk of an allision at the Key Bridge

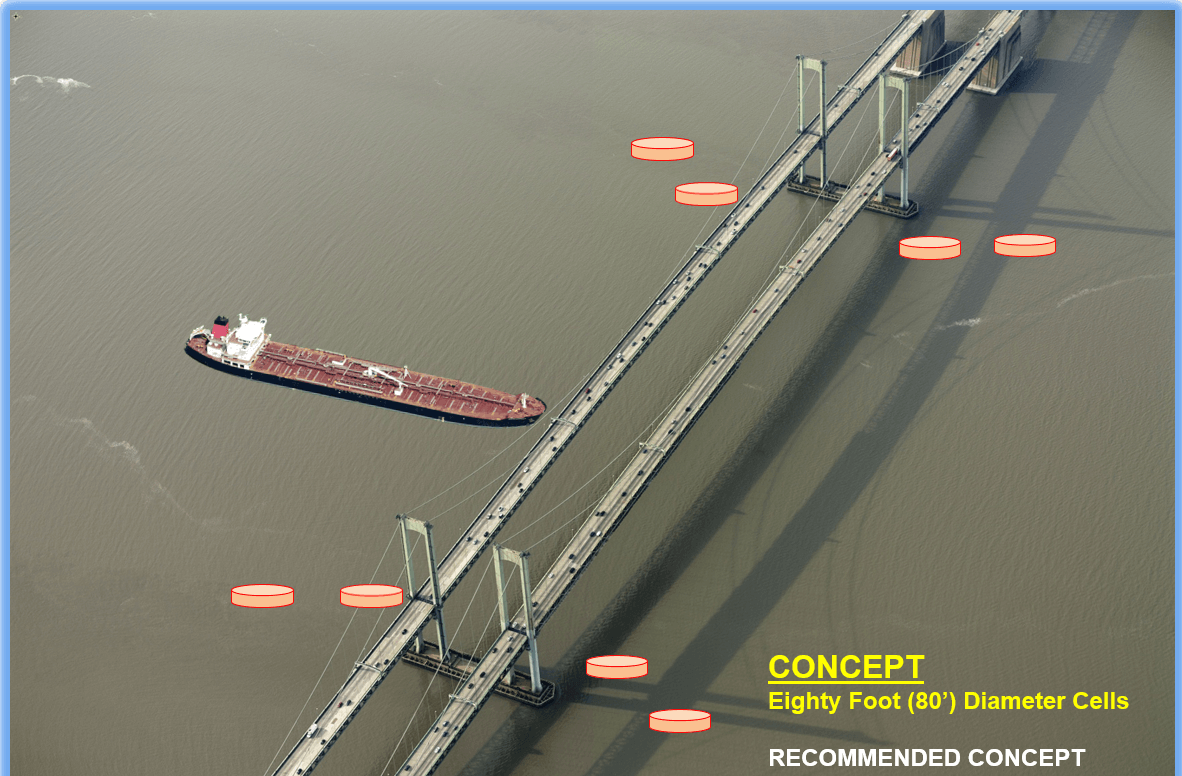

Nine years ago, in 2015, Delaware's bridge transport authority set aside $2.5 million to design new protective fenders for the Delaware Memorial Bridge. Tankers and boxships on the Delaware River were getting bigger, and the New Panama Canal would be bringing even larger ships to the Port of Wilmington soon.

In the unlikely event that one of these ships hit the Delaware Memorial Bridge's piers, it could potentially collapse the bridge, a Delaware River and Bay Authority spokesman told local media at the time. About 100,000 vehicles cross the eight-lane bridge every day, and it is vital to the region's economy.

This was too much risk for the DRBA. The agency hired consultants to design new protective bumpers of steel and rock (dolphins), and won a federal grant for $22 million to help pay for construction. The design spec for the new dolphins was intended to defend against a ship of up to 156,000 tonnes, moving at a speed of up to seven knots.

Illustration courtesy DRBA

Illustration courtesy DRBA

“[We've] come to the conclusion that these are the kind of protections that our bridges need,” Shekhar Scindia, a DRBA structural engineer, told Delaware Online in 2017. “Our complete preliminary design has been based on the calculations directed by the current code.”

They bundled the dolphin project into a large package of renovations, secured a permit from the Corps of Engineers, raised tolls on motorists, convinced two state governors to sign off on the cost, and issued bonds to raise funds. (This was not easy: New Jersey's governor initially vetoed the toll hikes, and DRBA had to negotiate to get the funding.)

Construction started on the eight protective steel-and-rock dolphins last year and should be done by 2025. The final cost will come to about $93 million.

“It never occurred to anybody”

On Tuesday, Baltimore's Francis Scott Key Bridge was struck by the Dali, a 10,000 TEU boxship. According to NTSB, she displaced (weighed) about 112,000 tonnes that day, including cargo, fuel and ballast - about 35,000 tonnes less than her maximum load. At about 0130, she slipped past the small dolphin on the bridge's southwest side, making about eight knots. When she hit the pier on the main span's support, the bridge collapsed within about 30 seconds, killing six and shutting down the ship channel with wreckage. The estimated cost of the casualty is in the range of $2-4 billion.

Four decades ago, the risk of a pier strike like this was on the minds of Maryland's highway engineers. In 1980, after a tanker struck and collapsed Florida's Sunshine Skyway Bridge, the Baltimore Sun quoted Maryland's top transport engineer saying that "a direct hit - it would knock [the Key Bridge] down."

But that hazard appears to have been forgotten in Maryland in recent years, two former highway agency officials told the Washington Post - even though the Key Bridge faced a similar threat as the Delaware Memorial Bridge, just 60 miles away on the same freeway system.

The idea of a ship hitting a pier on Baltimore's Key Bridge “never occurred to anybody," a former senior transport official told the Post. In recent years, risk-management conversations about the Key Bridge focused on acts of terror, like truck bombs, reflecting the post-9/11 security planning of the era, the official said.

The Dali allision involved approximately the same ship size, speed and outcome that Delaware authorities have been working to defend against at the Delaware Memorial Bridge since 2015. But even if Maryland transport officials had followed Delaware's lead, it is not clear that they could have done anything, engineering experts told the Washington Post. The center span on the Key Bridge is narrow, and installing protective dolphins or fenders would make it even narrower.

"That’s a pretty tight channel,” a former state transport official told the Post. "You might actually create a hazard rather than mitigate one."

Cost is also a factor. Engineers have to work within a budget, and the outside risk of a vessel strike has to compete with all the other risks and costs in the transport system, like traffic safety improvements and roadway repairs.

The National Transportation Safety Board - which first warned about the need for bridge pier protection in 1981 - is looking at the fender arrangements of the Key Bridge as part of its investigation.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.

No comments:

Post a Comment