Russia on Saturday hosts Intervision, an international song contest that was a regular fixture in Soviet states in the 1960s and ’70s. The revival follows Russia’s exclusion from Eurovision since its full-scale 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

Issued on: 20/09/2025 -

FRANCE24

By: Joanna YORK

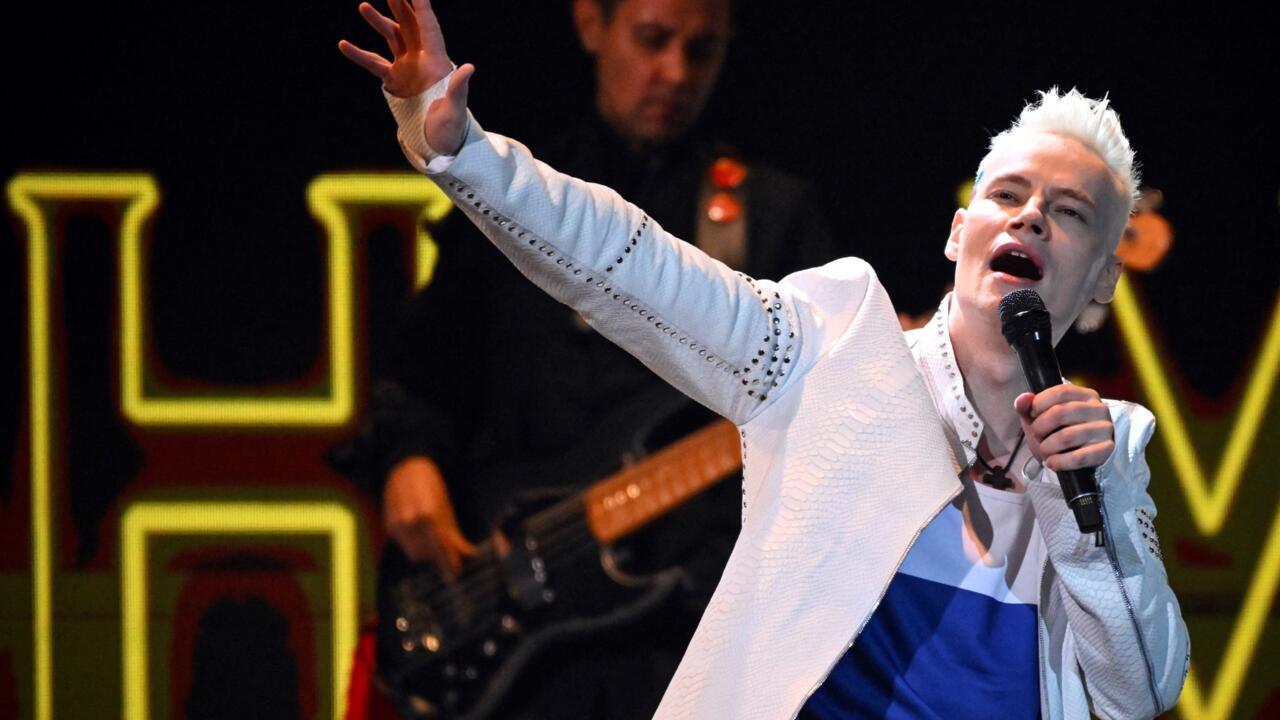

Russian pop idol Shaman (Yaroslav Dronov), performs on Moscow's Red Square on Flag Day, on August 22, 2024. © Alexander Nemenov, AFP

On Saturday night, the lights in Moscow’s 11,000-capacity Live Arena will go up on the Intervision song contest – marking the return of the Soviet-era counterpart to Europe’s pop juggernaut, Eurovision.

Compared with its heyday in the 1960s and ’70s, when Intervision was regularly held in Poland and mostly featured countries from the Eastern bloc, the 2025 revival promises a more global outlook.

The organisers of Saturday’s “spectacular show” have promised participants from around 20 countries – including Moscow’s heavyweight allies China, India and Saudi Arabia – as well as an entry from the United States.

Echoing Eurovision regulations – which ban songs with political messages – the Kremlin insists Intervision is not a political event but, rather, a forum for likeminded nations to promote “general cultural and spiritual values”.

“The Intervision competition is about talented people, not political decisions,” said Russia’s Culture Minister Olga Lyubimova.

But the line-up suggests otherwise. Russian contestant Yaroslav Dronov – who uses the stage name “Shaman” – is a prominent celebrity known for his support of the war in Ukraine and patriotic pop songs such as “Ya Russky” (I’m Russian).

Members of the jury are also far from impartial, including, for example, Colombia’s ambassador to Russia.

The event has “the hallmark of Kremlin-sponsored media and cultural projects”, says Dr Precious Chatterje-Doody, specialist in Russian foreign policy and senior lecturer at the Open University. “Despite the attempt to portray this as an inclusive international music event, it is political through and through.”

‘Legitimising the regime’

The return of Intervision comes three years after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine saw it expelled from the annual Eurovision Song Contest – a significant blow to the Kremlin’s image on the global stage.

Although Eurovision is often derided as kitsch, it is also a cultural behemoth that each year ranks among the world’s most-watched non-sporting events.

Official figures show 166 million people tuned in to the 2025 contest, which was broadcast by 37 media outlets, with online posts and videos garnering 2 billion views.

On Saturday night, the lights in Moscow’s 11,000-capacity Live Arena will go up on the Intervision song contest – marking the return of the Soviet-era counterpart to Europe’s pop juggernaut, Eurovision.

Compared with its heyday in the 1960s and ’70s, when Intervision was regularly held in Poland and mostly featured countries from the Eastern bloc, the 2025 revival promises a more global outlook.

The organisers of Saturday’s “spectacular show” have promised participants from around 20 countries – including Moscow’s heavyweight allies China, India and Saudi Arabia – as well as an entry from the United States.

Echoing Eurovision regulations – which ban songs with political messages – the Kremlin insists Intervision is not a political event but, rather, a forum for likeminded nations to promote “general cultural and spiritual values”.

“The Intervision competition is about talented people, not political decisions,” said Russia’s Culture Minister Olga Lyubimova.

But the line-up suggests otherwise. Russian contestant Yaroslav Dronov – who uses the stage name “Shaman” – is a prominent celebrity known for his support of the war in Ukraine and patriotic pop songs such as “Ya Russky” (I’m Russian).

Members of the jury are also far from impartial, including, for example, Colombia’s ambassador to Russia.

The event has “the hallmark of Kremlin-sponsored media and cultural projects”, says Dr Precious Chatterje-Doody, specialist in Russian foreign policy and senior lecturer at the Open University. “Despite the attempt to portray this as an inclusive international music event, it is political through and through.”

‘Legitimising the regime’

The return of Intervision comes three years after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine saw it expelled from the annual Eurovision Song Contest – a significant blow to the Kremlin’s image on the global stage.

Although Eurovision is often derided as kitsch, it is also a cultural behemoth that each year ranks among the world’s most-watched non-sporting events.

Official figures show 166 million people tuned in to the 2025 contest, which was broadcast by 37 media outlets, with online posts and videos garnering 2 billion views.

Crowds watch Sweden's KAJ perform at the Eurovision Song Contest in Basel, Switzerland, on May 17, 2025. © Martin Meissner, AP

For Moscow, Eurovision was a vehicle for “projecting soft power to the world and rewriting prevailing narratives about its values. It had a track record of sending songs that endorse peace and international harmony,” says William Lee Adams, Eurovision commentator and author of “Wild Dances: My Queer and Curious Journey to Eurovision.”

Hosting the 2009 Eurovision final in Moscow was an endeavour the Kremlin took seriously: the event was a $30 million extravaganza – then the most expensive in Eurovision history – including a stage so vast it used nearly a third of the world’s stock of LED screens.

A successful event was a way to “legitimise Putin’s regime” domestically and overseas, says Vitaly Kazakov, postdoctoral fellow at Aarhus University in Denmark and a specialist in the politics of cultural and sports events.

“It allowed the Russian political, cultural and economic elites to signal an image of domestic stability, prosperity and support for the Kremlin,” he adds.

For Moscow, Eurovision was a vehicle for “projecting soft power to the world and rewriting prevailing narratives about its values. It had a track record of sending songs that endorse peace and international harmony,” says William Lee Adams, Eurovision commentator and author of “Wild Dances: My Queer and Curious Journey to Eurovision.”

Hosting the 2009 Eurovision final in Moscow was an endeavour the Kremlin took seriously: the event was a $30 million extravaganza – then the most expensive in Eurovision history – including a stage so vast it used nearly a third of the world’s stock of LED screens.

A successful event was a way to “legitimise Putin’s regime” domestically and overseas, says Vitaly Kazakov, postdoctoral fellow at Aarhus University in Denmark and a specialist in the politics of cultural and sports events.

“It allowed the Russian political, cultural and economic elites to signal an image of domestic stability, prosperity and support for the Kremlin,” he adds.

The ‘decadent, liberal West’

Re-launching a home-grown counterpart to Eurovision gives Russia a chance to return to the global stage on its own terms.

At Intervision, “Russia can set the agenda of a music contest in opposition to the cultural initiatives of what it calls the ‘decadent, liberal West’, including Eurovision,” says Dr Ben Noble, associate professor of Russian politics at University College London.

Even before its expulsion, Russia was becoming an awkward fit at Eurovision. In 2014 – the year that Moscow illegally annexed Crimea and introduced sweeping anti-LBGT laws – Russia’s competition entry featured a pair of angelic-looking teenage twins performing on a giant see-saw.

“It was a surreal and theatrical bid for sympathy,” Adams says. “The audience booed them anyway.”

The Tolmachevy Sisters represented Russia at the Eurovision Song Contest in Copenhagen, Denmark, 2014. © Bax Lindhardt, AFP

Putin’s call for Intervision to reflect “traditional values” seems a direct rebuttal to Eurovision’s inclusive stance and the platform it gives former Soviet states – like Ukraine – to reassert their independence.

Since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Russia has also been banned from competing in the football World Cup and the Olympics, which Moscow tried to counterbalance by hosting the 2024 edition of the BRICS Games, an international multi-sport competition for emerging economies.

Hosting events like Intervision and the BRICS Games “remains important to the Russian authorities as a way of signalling to the Russian population and international audiences that things are ‘normal’, even despite the ongoing war,” says Kazakov.

They are also a chance for Moscow to “counter the narrative” that it is isolated on the world stage, says Noble, and to make the broader point “that Russia doesn’t just join the projects of other states – it can host its own initiatives, including international cultural events”.

‘More than half the world’

The inclusion of any Western performer at Intervison is rare – one of the only examples is the inclusion of Germany’s Boney M, which performed their disco hit Rasputin in 1979.

But this year, two Western performers will participate. R&B singer Brendan Howard, rumoured to be Michael Jackson’s son (he has denied the claims), will represent the United States while Balkan music legend Slobodan Trkulja will represent EU-candidate country Serbia.

Although Washington will not send an official delegation or take part in the jury, the US administration has not objected to Howard’s participation, according to the Russian foreign ministry.

The inclusion of two Western performers is an additional boon for Russia, says Kazakov. “It plays directly into its messaging about how the West is ‘divided’.”

According to Russian figures, the breadth of countries performing at Intervision could lead to unprecedented viewership.

The populations of the 23 participating countries make up “more than half the world”, noted Sergey Kiriyenko, chairman of the Intervision supervisory board, in comments to Russia’s Tass news agency, adding that 4.3 billion people will be able to watch the broadcast.

But how many will tune in?

Part of what makes Eurovision an enduring success is the fact that participating countries all watch at the same time and vote together, says Adams. In contrast, “there are 11 time zones between Brazil and Vietnam, both of whom are reportedly broadcasting Intervision”.

And a final word must go to the music itself. If Eurovision has carved itself a niche for flamboyant Europop that ranks highly in terms of entertainment value, what will Intervision offer as an alternative?

Putin’s call for a focus on “traditional values” could be the competition’s downfall.

“It could feel a bit too vanilla,” Adams observes.

“Those rules do not a pop banger make.”

Putin’s call for Intervision to reflect “traditional values” seems a direct rebuttal to Eurovision’s inclusive stance and the platform it gives former Soviet states – like Ukraine – to reassert their independence.

Since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Russia has also been banned from competing in the football World Cup and the Olympics, which Moscow tried to counterbalance by hosting the 2024 edition of the BRICS Games, an international multi-sport competition for emerging economies.

Hosting events like Intervision and the BRICS Games “remains important to the Russian authorities as a way of signalling to the Russian population and international audiences that things are ‘normal’, even despite the ongoing war,” says Kazakov.

They are also a chance for Moscow to “counter the narrative” that it is isolated on the world stage, says Noble, and to make the broader point “that Russia doesn’t just join the projects of other states – it can host its own initiatives, including international cultural events”.

‘More than half the world’

The inclusion of any Western performer at Intervison is rare – one of the only examples is the inclusion of Germany’s Boney M, which performed their disco hit Rasputin in 1979.

But this year, two Western performers will participate. R&B singer Brendan Howard, rumoured to be Michael Jackson’s son (he has denied the claims), will represent the United States while Balkan music legend Slobodan Trkulja will represent EU-candidate country Serbia.

Although Washington will not send an official delegation or take part in the jury, the US administration has not objected to Howard’s participation, according to the Russian foreign ministry.

The inclusion of two Western performers is an additional boon for Russia, says Kazakov. “It plays directly into its messaging about how the West is ‘divided’.”

According to Russian figures, the breadth of countries performing at Intervision could lead to unprecedented viewership.

The populations of the 23 participating countries make up “more than half the world”, noted Sergey Kiriyenko, chairman of the Intervision supervisory board, in comments to Russia’s Tass news agency, adding that 4.3 billion people will be able to watch the broadcast.

But how many will tune in?

Part of what makes Eurovision an enduring success is the fact that participating countries all watch at the same time and vote together, says Adams. In contrast, “there are 11 time zones between Brazil and Vietnam, both of whom are reportedly broadcasting Intervision”.

And a final word must go to the music itself. If Eurovision has carved itself a niche for flamboyant Europop that ranks highly in terms of entertainment value, what will Intervision offer as an alternative?

Putin’s call for a focus on “traditional values” could be the competition’s downfall.

“It could feel a bit too vanilla,” Adams observes.

“Those rules do not a pop banger make.”

No comments:

Post a Comment