Story by CBC/Radio-Canada

Dec. 20, 2025.

Every year, snowy owls spread their wings and migrate down to the Prairies, where they enjoy access to plenty of rodent prey in vast open spaces.

But this year's migration is the first of its kind, marked by the recent classification of snowy owls as a threatened species.

That designation was announced in May by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC), which assesses the at-risk status of native species and provides recommendations to the federal government.

Louise Blight, an adjunct associate professor at the University of Victoria's School of Environmental Studies and co-chair of the COSEWIC birds specialist sub-committee, said the decision to designate snowy owls as a threatened species was not made lightly. But, she said, their population has declined about 40 per cent in the past 24 years.

Snowy owls face many challenges, including habitat loss in their Arctic nesting grounds due to climate change, Blight said. Warming temperatures are melting sea ice, reducing platforms for the owls to sit on when hunting.

Snowy owls are also impacted by avian influenza — both contracting it and losing winter prey to the virus, said Blight. There have been 15 cases of avian influenza found in snowy owls in Canada since 2021, according to data compiled by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency.

Snowy owls face even more challenges when they embark on their lengthy migrations south. In their wintering grounds, they can be hit by vehicles, electrocuted by power lines, tangled in human structures, and become poisoned after eating prey that has been exposed to rodenticide.

Colin Weir, managing director of the Alberta Birds of Prey Foundation wildlife rehabilitation centre in Coaldale, has dealt with raptors affected by all of those.

"A lot of times when snowy owls come down from the Arctic ... they're coming into new areas with lots of man-made hazards around," Weir said.

Alberta Birds of Prey Foundation managing director Colin Weir holds a flightless snowy owl, which is one of two that became permanent residents of the facility after being hit by cars. (Amir Said/CBC)

The centre cares for injured birds from across Canada, and is currently home to two snowy owls that ended up unable to be released after being hit by cars.

"The thing to remember about roadways is they have ditches, which collect a lot of moisture and attract a lot of ground rodents," Weir said. "So, that's why birds get hit by cars. The roadside ditches are basically like buffet restaurants to them."

Weir said the busiest time for bird collisions in Alberta is May to September, as most migratory birds of prey are back from overwintering farther south at that time, but that's not the case for snowy owls.

"Just watching for wildlife in general is probably the number one thing," Weir said. "Not only for the safety of the creatures themselves, but just for people's own personal safety as well."

Snowy owls can be found in every Canadian province following their winter migration. NatureCounts, a biodiversity data platform operated by Birds Canada, estimates there are 15,000 snowy owls in the country — more than half of the estimated global population of 29,000.

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature classifies the worldwide population of snowy owls as vulnerable.

Tracking snowy owl numbers is tricky, scientist says

Snowy owls are particularly difficult to survey because of their nomadic nature, said Lisa Takats Priestley.

"They don't have sort of direct corridors," said Priestley, a wildlife biologist who has been studying owl populations and movement patterns for more than 20 years. "They're very hard to work with as far as trapping and banding."

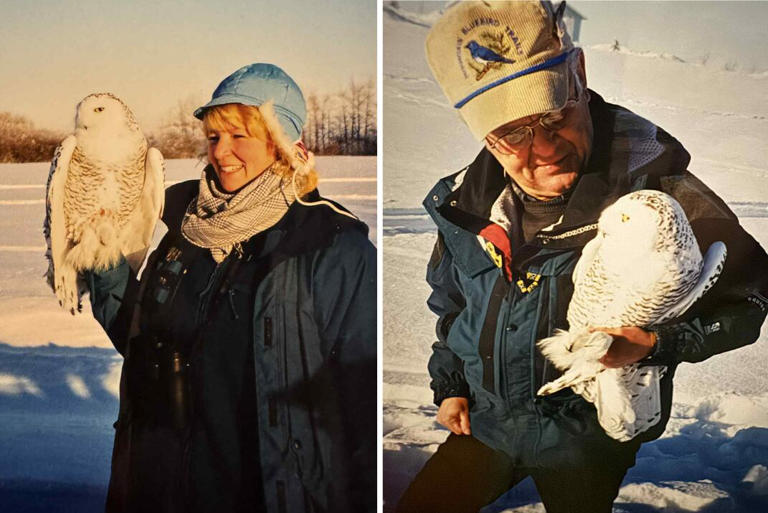

Researchers Lisa Takats Priestley, left, and Hardy Pletz pictured banding snowy owls in Fort Saskatchewan, Alta. Owl banding involves capturing the birds and putting bands on them to track populations and movement patterns for scientific purposes. One snowy owl banded by Pletz was first captured in 1994 and then recaptured in 2013, making it one of the oldest known wild snowy owls. (Submitted by Lisa Takats Priestley)

She said attaching transmitters to snowy owls has offered more insight into their movement patterns, but that does little to confirm population changes.

Much of the data on snowy owl numbers comes from Christmas Bird Counts, an annual citizen science initiative in which thousands of volunteers across Canada count all the birds they see in a specific area.

Because snowy owl movement patterns tend to be unpredictable, trying to track population trends based on visual counts may not be enough, Priestley said.

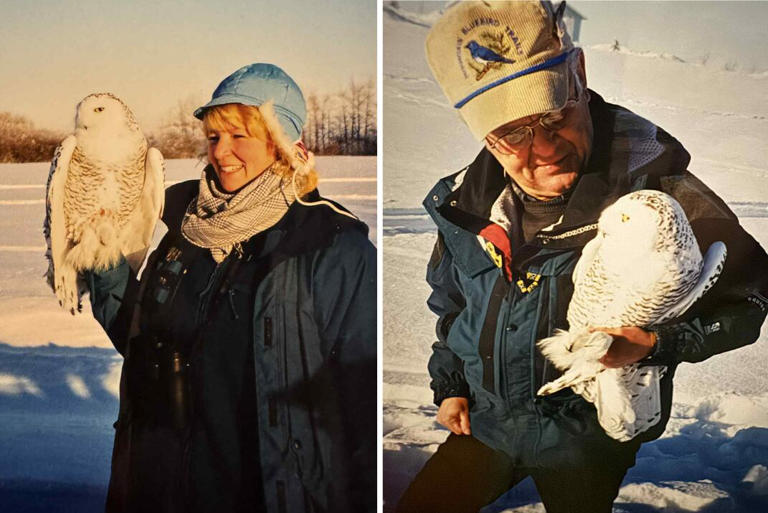

A snowy owl in southern Alberta, where the birds can be found looking for prey in open fields following their annual migration. Snowy owls travel from the Arctic to locations throughout Canada and the U.S. every year. (Amir Said/CBC)

Because of their recent designation as a threatened species in Canada, there might be an increased interest — and effort — from researchers to better understand snowy owl numbers.

"Now that snowy owl is listed, there will be a push to use more of the data collected from a variety of sources to help us understand where there may be more concerns in certain parts of the owl's range," Priestley said.

Every year, snowy owls spread their wings and migrate down to the Prairies, where they enjoy access to plenty of rodent prey in vast open spaces.

But this year's migration is the first of its kind, marked by the recent classification of snowy owls as a threatened species.

That designation was announced in May by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC), which assesses the at-risk status of native species and provides recommendations to the federal government.

Louise Blight, an adjunct associate professor at the University of Victoria's School of Environmental Studies and co-chair of the COSEWIC birds specialist sub-committee, said the decision to designate snowy owls as a threatened species was not made lightly. But, she said, their population has declined about 40 per cent in the past 24 years.

Snowy owls face many challenges, including habitat loss in their Arctic nesting grounds due to climate change, Blight said. Warming temperatures are melting sea ice, reducing platforms for the owls to sit on when hunting.

Snowy owls are also impacted by avian influenza — both contracting it and losing winter prey to the virus, said Blight. There have been 15 cases of avian influenza found in snowy owls in Canada since 2021, according to data compiled by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency.

Snowy owls face even more challenges when they embark on their lengthy migrations south. In their wintering grounds, they can be hit by vehicles, electrocuted by power lines, tangled in human structures, and become poisoned after eating prey that has been exposed to rodenticide.

Colin Weir, managing director of the Alberta Birds of Prey Foundation wildlife rehabilitation centre in Coaldale, has dealt with raptors affected by all of those.

"A lot of times when snowy owls come down from the Arctic ... they're coming into new areas with lots of man-made hazards around," Weir said.

Alberta Birds of Prey Foundation managing director Colin Weir holds a flightless snowy owl, which is one of two that became permanent residents of the facility after being hit by cars. (Amir Said/CBC)

The centre cares for injured birds from across Canada, and is currently home to two snowy owls that ended up unable to be released after being hit by cars.

"The thing to remember about roadways is they have ditches, which collect a lot of moisture and attract a lot of ground rodents," Weir said. "So, that's why birds get hit by cars. The roadside ditches are basically like buffet restaurants to them."

Weir said the busiest time for bird collisions in Alberta is May to September, as most migratory birds of prey are back from overwintering farther south at that time, but that's not the case for snowy owls.

"Just watching for wildlife in general is probably the number one thing," Weir said. "Not only for the safety of the creatures themselves, but just for people's own personal safety as well."

Snowy owls can be found in every Canadian province following their winter migration. NatureCounts, a biodiversity data platform operated by Birds Canada, estimates there are 15,000 snowy owls in the country — more than half of the estimated global population of 29,000.

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature classifies the worldwide population of snowy owls as vulnerable.

Tracking snowy owl numbers is tricky, scientist says

Snowy owls are particularly difficult to survey because of their nomadic nature, said Lisa Takats Priestley.

"They don't have sort of direct corridors," said Priestley, a wildlife biologist who has been studying owl populations and movement patterns for more than 20 years. "They're very hard to work with as far as trapping and banding."

Researchers Lisa Takats Priestley, left, and Hardy Pletz pictured banding snowy owls in Fort Saskatchewan, Alta. Owl banding involves capturing the birds and putting bands on them to track populations and movement patterns for scientific purposes. One snowy owl banded by Pletz was first captured in 1994 and then recaptured in 2013, making it one of the oldest known wild snowy owls. (Submitted by Lisa Takats Priestley)

She said attaching transmitters to snowy owls has offered more insight into their movement patterns, but that does little to confirm population changes.

Much of the data on snowy owl numbers comes from Christmas Bird Counts, an annual citizen science initiative in which thousands of volunteers across Canada count all the birds they see in a specific area.

Because snowy owl movement patterns tend to be unpredictable, trying to track population trends based on visual counts may not be enough, Priestley said.

A snowy owl in southern Alberta, where the birds can be found looking for prey in open fields following their annual migration. Snowy owls travel from the Arctic to locations throughout Canada and the U.S. every year. (Amir Said/CBC)

Because of their recent designation as a threatened species in Canada, there might be an increased interest — and effort — from researchers to better understand snowy owl numbers.

"Now that snowy owl is listed, there will be a push to use more of the data collected from a variety of sources to help us understand where there may be more concerns in certain parts of the owl's range," Priestley said.

No comments:

Post a Comment