Sunken worlds under the Pacific?

ETH Zurich

image:

A new computer model visualizes material in the lower mantle that cannot come from subducted plates.

view moreCredit: Sebastian Noe / ETH Zurich

No one can see inside the Earth. Nor can anyone drill deep enough to take rock samples from the mantle, the layer between Earth’s core and outermost, rigid layer the lithosphere, or measure temperature and pressure there. That's why geophysicists use indirect methods to see what's going on deep beneath our feet.

For example, they use seismograms, or earthquake recordings, to determine the speed at which earthquake waves propagate. They then use this information to calculate the internal structure of the Earth. This is very similar to how doctors use ultrasound to image organs, muscles or veins inside the body without opening it up.

Seismic waves provide information

Here's how it works: when the Earth trembles, seismic waves spread out from the epicentre in all directions. On their way through the Earth, they are refracted, diffracted or reflected. The speed at which the waves spread depends on the type of wave, but also on the density and elasticity of the material through which the waves pass. Seismographic stations record these different waves, and on the basis of these recordings, geophysicists can draw conclusions about the structure and composition of the Earth and examine the processes that take place inside it.

Using seismic recordings, Earth scientists determined the position of submerged tectonic plates throughout the Earth's mantle. They always found them where they expected them to be: in an area known as subduction zones, where two plates meet and one subducts beneath the other into the Earth's interior. This has helped scientists investigate the plate tectonic cycle, i.e., the emergence and destruction of plates at Earth’s surface, through our planet’s history.

Plate remnants where there shouldn't be any

Now, however, a team of geophysicists from ETH Zurich and the California Institute of Technology has made a surprising discovery: using a new high-resolution model, they have discovered further areas in the Earth's interior that look like the remains of submerged plates. Yet, these are not located where they were expected; instead, they are under large oceans or in the interior of continents – far away from plate boundaries. There is also no geological evidence of past subduction there. This study was recently published in the journal Scientific Reports.

What is new about their modelling approach is that the ETH researchers are not just using one type of earthquake wave to study the structure of the Earth's interior, but all of them. Experts call the procedure full-waveform inversion. This makes the model very computationally intensive, which is why the researchers used the Piz Daint supercomputer at the CSCS in Lugano. Is there a lost world beneath the Pacific Ocean?

“Apparently, such zones in the Earth's mantle are much more widespread than previously thought,” says Thomas Schouten, first author and doctoral student at the Geological Institute of ETH Zurich.

One of the newly discovered zones is under the western Pacific. However, according to current plate tectonic theories and knowledge, there should be no material from subducted plates there, because it is impossible that there were subduction zones nearby in the recent geological history. The researchers do not know for certain what material is involved instead, and what that would mean for Earth’s internal dynamics. “That's our dilemma. With the new high-resolution model, we can see such anomalies everywhere in the Earth's mantle. But we don't know exactly what they are or what material is creating the patterns we have uncovered.”

It's like a doctor who has been examining blood circulation with ultrasound for decades and finds arteries exactly where he expects them, says ETH professor Andreas Fichtner. “Then if you give him a new, better examination tool, he suddenly sees an artery in the buttock that doesn't really belong there. That's exactly how we feel about the new findings,” explains the wave physicist. He developed the model in his group and wrote the code.

Extracting more information from waves

So far, the researchers can only speculate. “We think that the anomalies in the lower mantle have a variety of origins,” says Schouten. He believes it is possible that they are not just cold plate material that has subducted in the last 200 million years, as previously assumed. “It could be either ancient, silica-rich material that has been there since the formation of the mantle about 4 billion years ago and has survived despite the convective movements in the mantle, or zones where iron-rich rocks accumulate as a consequence of these mantle movements over billions of years” he notes.

For the doctoral student, this means above all that more research with even better models is needed to see further details of Earth’s interior. “The waves we use for the model essentially only represent one property, namely the speed at which they travel through the Earth's interior,” says the Earth scientist. However, this does not do justice to the Earth's complex interior. “We have to calculate the different material parameters that could generate the observed speeds of the different wave types. Essentially, we have to dive deeper into the material properties behind the wave speed,” says Schouten.

Journal

Scientific Reports

Method of Research

Computational simulation/modeling

Article Title

Full-waveform inversion reveals diverse origins of lower mantle positive wave speed anomalies

James Churchward - Wikipedia

Churchward was born in Bridestow, Okehampton, Devon at Stone House to Henry and Matilda (née Gould) Churchward. James had four brothers and four sisters. In November 1854, Henry died and the family moved in with Matilda's parents in the hamlet of Kigbear, near Okehampton. Census records indicate the family next moved to London when James was 18 after his grandfather George Gould died.

THE SACRED SYMBOLS OF MU - James Churchward

COLONEL JAMES CHURCHWARD AUTHOR OF "THE LOST CONTINENT OF MU" "THE CHILDREN OF MU" ILLUSTRATED IVES WASHBURN; NEW YORK Scanned at sacred-texts.com, December, 2003.

3 Beards Podcast: Is the Lost Continent of Mu Real?

Author Jack Churchward joins the show to talk about his books that cover The Lost Continent of Mu, a subject brought to life by the works of his great grandfather Col. James Churchward.

Lifting the Veil on the Lost Continent of Mu: The Motherland of Men

The Stone Tablets of Mu

Crossing the Sands of Time

are books Jack Churchward has penned to cover the works of his great grandfather and bring into focus on what is fact and what is fiction.

The mythical idea of the “Land of Mu” first appeared in the works of the British-American antiquarian Augustus Le Plongeon (1825–1908), after his investigations of the Maya ruins in Yucatán. He claimed that he had translated the first copies of the Popol Vuh, the sacred book of the K’iche’ from the ancient Mayan using Spanish. He claimed the civilization of Yucatán was older than those of Greece and Egypt, and told the story of an even older continent.

Col. James Churchward claimed that the landmass of Mu was located in the Pacific Ocean, and stretched east–west from the Marianas to Easter Island, and north–south from Hawaii to Mangaia. According to Churchward the continent was supposedly 5,000 miles from east to west and over 3,000 miles from north to south, which is larger than South America. The continent was believed to be flat with massive plains, vast rivers, rolling hills, large bays, and estuaries. He claimed that according to the creation myth he read in the Indian tablets, Mu had been lifted above sea level by the expansion of underground volcanic gases. Eventually Mu “was completely obliterated in almost a single night” after a series of earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, “the broken land fell into that great abyss of fire” and was covered by “fifty millions of square miles of water.” Churchward claimed the reasoning for the continent’s destruction in one night was because the main mineral on the island was granite and was honeycombed to create huge shallow chambers and cavities filled with highly explosive gases. Once the chambers were empty after the explosion, they collapsed on themselves, causing the island to crumble and sink.

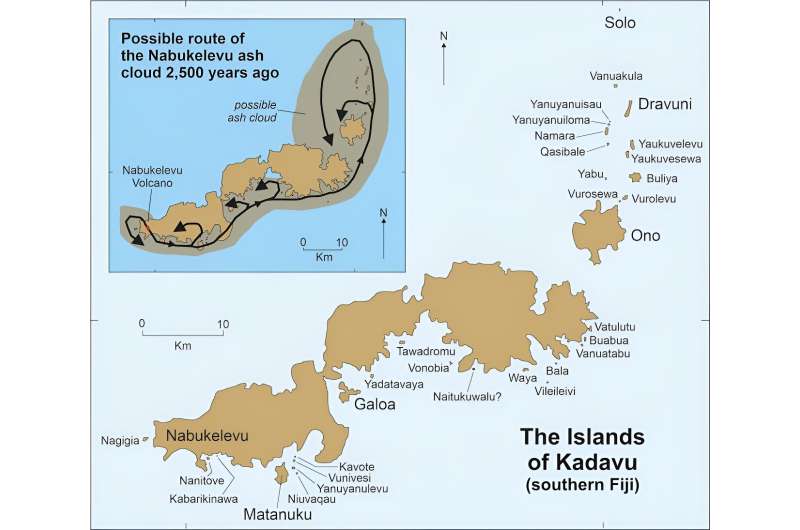

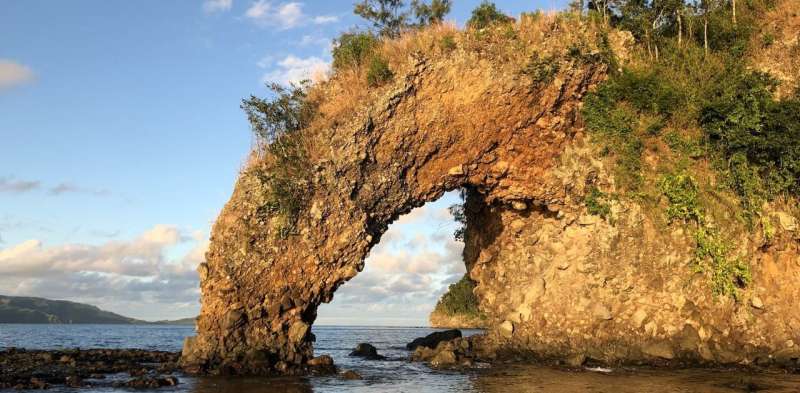

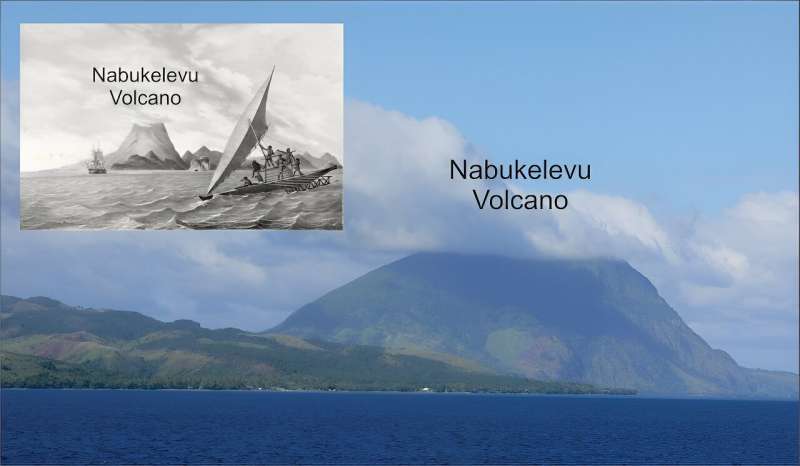

Nabukelevu from the northeast, its top hidden in cloud. Inset: Nabukelevu from the west in 1827 after the drawing by the artist aboard the Astrolabe, the ship of French explorer Dumont d’Urville. It is an original lithograph by H. van der Burch after original artwork by Louis Auguste de Sainson. Credit: Wikimedia Commons; Australian National Maritime Museum,

Nabukelevu from the northeast, its top hidden in cloud. Inset: Nabukelevu from the west in 1827 after the drawing by the artist aboard the Astrolabe, the ship of French explorer Dumont d’Urville. It is an original lithograph by H. van der Burch after original artwork by Louis Auguste de Sainson. Credit: Wikimedia Commons; Australian National Maritime Museum,