The Glee You See From Fascists About State Violence is a Sexual Fetish

January 14, 2026

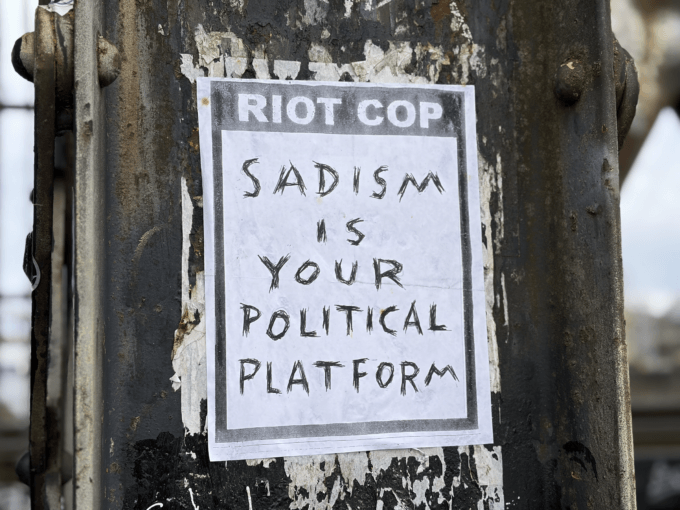

Photograph by Nathaniel St. Clair

There is a psychology at the root of what we are seeing behind the behavior MAGA fascists and far-right media these past few weeks that isn’t being addressed. One which is behind how they so openly defend the murder of an unarmed woman. Or how they cheer on the Trump regime’s imperialistic fever dreams. And all of this, while none of it improves their own life circumstances in the least.

If these people were to be transported back in time to when slavery was the law of the land, they would have adored the overseers and the bounty hunters and applauded any violence against runaway enslaved people or abolitionists. If they were transported back to 1930’s Germany, they would have cheered the Geheime Staatspolizei as they beat and rounded up communists, Roma, queer people and Jews in the streets. It isn’t a new script. It is the same story of grievance played out in a new setting.

The people who are most susceptible to this are notorious for suppressing sexual desires. And thus, there is an enormous amount of repressed fetishism happening within the celebration of ICE violence. They find unchecked, unaccountable power enticing. Its sadism is intoxicating because it allows them to disassociate from the crushing weight of their own inner turmoil. And because virtually none of them have ever taken the time to examine their own shadows, they project them onto everyone and everything.

This psychology of sadomasochism is not the kind one finds in consensual BDSM relationships or communities. Quite the opposite. The people who participate in consensual BDSM do it because it is cathartic. Because it is fun. Because they trust their partner.

But the kind we see among far-right and fascist groups is solely about demeaning those who have not submitted to the state or to a mob. This is a dynamic that extols an arrangement of power based solely upon punishment and cruelty against a dehumanized other. In this way, the supporters of ICE violence or the Trump regime’s cruelty are positioned as the voyeur, and thus derive pleasure from observing the pain meted out on a scapegoated and dehumanized other, on those who dissent, or anyone who gets in the way of power.

This plays out most especially in misogynistic terms. Patriarchal authoritarianism serves as the foundation for fascist psychopathology. Conservative patriarchal religion provides a framework for both the repression of sexual desire and human sexuality in general, and the oppression of women. And violence, from the burning or witches to the denial of reproductive rights, has often been the result. Fascism merely draws on this dark history of misogyny.

We see this clearly in the murder of Renee Nicole Good. A woman stood in the way of a man’s power. Her wife mocked him. Although they presented no danger to his life, they signified that they did not recognize his dominance. Thus, Good had to be punished. Shot in the face, which is the most intimate form of murder. That Good was later revealed to be in a lesbian relationship provided more ammunition for MAGA fascists. She was swiftly painted by far-right media as a traitor to her gender.

Wilhelm Reich wrote more about this in his book The Psychology of Fascism:

“More than economic dependency of the wife and children on the husband and father is needed to preserve the institution of the authoritarian family [and its support of the authoritarian state]. For the suppressed classes, this dependency is endurable only on condition that the consciousness of being a sexual being is suspended as completely as possible in women and in children. The wife must not figure as a sexual being, but solely as a child-bearer. Essentially, the idealization and deification of motherhood, which are so flagrantly at variance with the brutality with which the mothers of the toiling masses are actually treated, serve as means of preventing women from gaining a sexual consciousness, of preventing the imposed sexual repression from breaking through and of preventing sexual anxiety and sexual guilt-feelings from losing their hold. Sexually awakened women, affirmed and recognized as such, would mean the complete collapse of the authoritarian ideology.”

― Wilhelm Reich, The Mass Psychology of Fascism

White supremacist, Nick Fuentes, said: “You should not seek sex because if you seek sex you will become gay because sex is a gay act.” He elaborated on this thought with: “the straightest thing you could do is to never have sex.” The homophobia and sheer absurdity of these statements aside, it underscores the sexual repression at the heart of fascist thinking. It is a belief that sexual pleasure itself is to be rejected. It may appear contradictory, but it goes hand in hand with the notion that the only role women play in society is to bear and raise children. It is also why transgender people are so often a target of far-right malice. Their very existence is a challenge to an order that they see as essential and God-ordained.

The contradictory nature of fascist thinking is a primary feature. It is how many of them could express anger about the Epstein Files, while ignoring that their leader, Donald Trump, figures large in their pages. It is how they can express devotion to religious institutions which have covered up child abuse for decades, while condemning drag queens. In sum, fascism is more about optics, than facts. It is about upholding traditional mores and myths, and strict gender roles, than human equality. It is about charismatic heterosexual male strongmen rather than things that are considered feminine, like empathy and kindness.

The seduction of state violence is nothing new. And it will always attract a segment of the population, mostly disaffected men. But the American project, with its characteristic predatory capitalism and Calvinist Christian patriarchal roots, has allowed it to grow and become emboldened. Racialized, Indigenous and queer women have known this violence since the first European set foot in North America, often meted out to them by white women who enjoyed a certain measure of privilege in a racist society. This is not to say white women were not also brutalized or treated as property, they were. But racialized and queer women have never enjoyed the same privilege.

As we see more and more incidents of ICE violence and the subsequent praise it receives from fascists, primarily fascist men, we should take time to understand the corrosive pathology at the root of it all. Fascism channels its sexual repression into aggression and absolute submission to charismatic male leaders and grand narratives about nationalistic glory. It thrives on the denigration, humiliation, torture and murder of dehumanized others. And it targets young men.

Understanding this may help us realize where it is coming from, how to oppose it effectively, and how to help a new generation of boys escape a similar fate.

The Pathology of Power: How America Learned to Love State Violence

There’s a scene playing out across American social media that should disturb anyone with a functioning conscience.

A woman lies dead, killed by federal agents while serving as a legal observer. The video evidence is clear: she was waving ICE vehicles forward, her SUV was moving with its wheels turned away from officers, and the fatal shots came from an agent standing to the side with ample space to disengage. Yet in comment sections across the internet, thousands celebrate her death with gleeful acronyms like “FAFO” – Fuck Around and Find Out.

This isn’t an isolated pathology. It’s the same reflex that defended George Floyd’s nine-minute murder under a cop’s knee. The same impulse that mocked Eric Garner’s final words – “I can’t breathe” – as he was choked to death for selling loose cigarettes. The same sickness that turns every police killing into a referendum on the victim’s character, clothing, compliance, or decisions made in fear of state violence.

What we are watching is a culture that has learned to reflexively sanctify the trigger pull, to treat human life as disposable when it inconveniences power, and to experience vicarious pleasure in watching the state kill people who step out of line.

This is what moral rot looks like when it reaches the core.

There’s a scene playing out across American social media that should disturb anyone with a functioning conscience.

A woman lies dead, killed by federal agents while serving as a legal observer. The video evidence is clear: she was waving ICE vehicles forward, her SUV was moving with its wheels turned away from officers, and the fatal shots came from an agent standing to the side with ample space to disengage. Yet in comment sections across the internet, thousands celebrate her death with gleeful acronyms like “FAFO” – Fuck Around and Find Out.

This isn’t an isolated pathology. It’s the same reflex that defended George Floyd’s nine-minute murder under a cop’s knee. The same impulse that mocked Eric Garner’s final words – “I can’t breathe” – as he was choked to death for selling loose cigarettes. The same sickness that turns every police killing into a referendum on the victim’s character, clothing, compliance, or decisions made in fear of state violence.

What we are watching is a culture that has learned to reflexively sanctify the trigger pull, to treat human life as disposable when it inconveniences power, and to experience vicarious pleasure in watching the state kill people who step out of line.

This is what moral rot looks like when it reaches the core.

The Psychology of Victim-Blaming

The comments celebrating and defending Renee Good’s death reveal a psychological pattern familiar to anyone who has studied authoritarian movements: the sadistic pleasure derived from watching power crush the powerless. It’s the same impulse that filled Roman coliseums and medieval execution squares. What should disturb us most is not that such impulses exist – they are part of our evolutionary inheritance – but that contemporary American culture actively cultivates and normalizes them.

When someone types “Yep, still a good shoot” with a meme of Tom Cruise grinning that says “Deal with it” in response to footage of a woman being killed, they are engaging in a form of participatory violence. They are experiencing the pleasure of dominance without the moral burden of pulling the trigger themselves. The state becomes their instrument, and every killing becomes a validation of their worldview: that those who do not perfectly comply with authority deserve to be killed.

This is victim-blaming in its most lethal form. Just as rape culture asks “But what was she wearing?” police violence culture asks “Why didn’t she just comply?”

Both deflect accountability from the person wielding power to the person experiencing violence.

Both manufacture justifications by scrutinizing the victim’s behavior rather than the perpetrator’s choice to commit violence.

Both require us to accept a sick logic: that somehow, the victim brought this on herself.

Rape culture follows a familiar script:

- “She was drinking”

- She shouldn’t have been at that party”

- “She went to his room”

- “She was flirting with him”

- “She didn’t fight back hard enough”

- “She didn’t say no clearly enough”

- “Why did she wait so long to report it?”

- “She has a history of…”

But let’s be absolutely clear. As the late Dick Gregory put it: “If I’m a woman and I’m walking down the street naked, you STILL don’t have a right to rape me.”

You see, the clothing was never the issue—the rapist’s choice to commit violence was. Police violence culture operates identically: absolutely nothing Renee Good did warranted lethal force. She could have been blocking traffic, she could have been scared by the assaulting officer trying to suddenly force her door open, she could have tried to drive away—none of it justifies lethal force.

Both systems train us to ask the wrong questions.

Not “Why did he choose to rape?” but “What was she wearing?”

Not “Why did the officer shoot someone driving away?” but “Why didn’t she comply?”

The interrogation always flows toward the victim, excavating any detail that might transform violence into something the victim brought upon themselves.

And just as crucially, both systems ignore the role of the aggressor in creating the crisis they claim justified their violence. Seconds before Renee Good was killed, the situation was calm. Her final words to one officer were “It’s fine, dude. I’m not mad at you.” Then another agent dramatically escalated—yelling “get out of the car” while forcefully trying to open her door, creating the very fear and panic that preceded her attempt to leave. No one asks why he chose that escalation. No one questions why he transformed a de-escalated moment into a chaotic confrontation. The focus remains laser-fixed on her response to the panic he created, never on his choice to create it.

This is the pattern: agents of power escalate, then claim the victim’s reaction to that escalation justified further violence. She panicked because he made her panic. She tried to leave because staying felt dangerous. Then they killed her for the fear they manufactured and called it self-defense.

The comments celebrating and defending Renee Good’s death reveal a psychological pattern familiar to anyone who has studied authoritarian movements: the sadistic pleasure derived from watching power crush the powerless. It’s the same impulse that filled Roman coliseums and medieval execution squares. What should disturb us most is not that such impulses exist – they are part of our evolutionary inheritance – but that contemporary American culture actively cultivates and normalizes them.

When someone types “Yep, still a good shoot” with a meme of Tom Cruise grinning that says “Deal with it” in response to footage of a woman being killed, they are engaging in a form of participatory violence. They are experiencing the pleasure of dominance without the moral burden of pulling the trigger themselves. The state becomes their instrument, and every killing becomes a validation of their worldview: that those who do not perfectly comply with authority deserve to be killed.

This is victim-blaming in its most lethal form. Just as rape culture asks “But what was she wearing?” police violence culture asks “Why didn’t she just comply?”

Both deflect accountability from the person wielding power to the person experiencing violence.

Both manufacture justifications by scrutinizing the victim’s behavior rather than the perpetrator’s choice to commit violence.

Both require us to accept a sick logic: that somehow, the victim brought this on herself.

Rape culture follows a familiar script:

- “She was drinking”

- She shouldn’t have been at that party”

- “She went to his room”

- “She was flirting with him”

- “She didn’t fight back hard enough”

- “She didn’t say no clearly enough”

- “Why did she wait so long to report it?”

- “She has a history of…”

But let’s be absolutely clear. As the late Dick Gregory put it: “If I’m a woman and I’m walking down the street naked, you STILL don’t have a right to rape me.”

You see, the clothing was never the issue—the rapist’s choice to commit violence was. Police violence culture operates identically: absolutely nothing Renee Good did warranted lethal force. She could have been blocking traffic, she could have been scared by the assaulting officer trying to suddenly force her door open, she could have tried to drive away—none of it justifies lethal force.

Both systems train us to ask the wrong questions.

Not “Why did he choose to rape?” but “What was she wearing?”

Not “Why did the officer shoot someone driving away?” but “Why didn’t she comply?”

The interrogation always flows toward the victim, excavating any detail that might transform violence into something the victim brought upon themselves.

And just as crucially, both systems ignore the role of the aggressor in creating the crisis they claim justified their violence. Seconds before Renee Good was killed, the situation was calm. Her final words to one officer were “It’s fine, dude. I’m not mad at you.” Then another agent dramatically escalated—yelling “get out of the car” while forcefully trying to open her door, creating the very fear and panic that preceded her attempt to leave. No one asks why he chose that escalation. No one questions why he transformed a de-escalated moment into a chaotic confrontation. The focus remains laser-fixed on her response to the panic he created, never on his choice to create it.

This is the pattern: agents of power escalate, then claim the victim’s reaction to that escalation justified further violence. She panicked because he made her panic. She tried to leave because staying felt dangerous. Then they killed her for the fear they manufactured and called it self-defense.

A Culture of Normalized Violence

This pathology didn’t emerge spontaneously. It was carefully constructed through decades of policy choices, media narratives, and cultural conditioning.

Start with the militarization of American policing. When we equip local police departments with armored vehicles, automatic weapons, and training that emphasizes “warrior mentality” over community service, we shouldn’t be surprised when they treat citizens as enemy combatants. The weapons don’t just kill—they shape psychology. Officers trained to see lethal threats everywhere will escalate situations until their fears materialize, then cite the crisis they created as proof they were right all along.

Add qualified immunity, which shields officers from accountability for all but the most egregious violations. When cops know they can kill with minimal consequences – perhaps a paid administrative leave, perhaps a transfer to another department – the incentive structure actively encourages lethal force. Why take the time to de-escalate when you can shoot and face no meaningful punishment?

Layer on media narratives that frame every police encounter as life-or-death drama, every person killed as a “dangerous criminal,” every protest as a riot. Decades of “copaganda” shows like Law & Order have trained Americans to identify with the badge, to experience every limit on police power as a personal threat, to see civil liberties as obstacles to justice rather than its foundation.

The result is a culture of learned helplessness and moral resignation. We accept as inevitable what other democracies consider intolerable.

In Sweden, police are trained to treat lethal force as a genuine last resort. De-escalation is mandatory. Firing at vehicles is extraordinarily rare. Officers face real investigation and prosecution when force is unjustified. The result? Dramatically fewer police killings – not chaos, not crime spikes, but a society that manages to maintain order without treating human life as disposable.

American culture shrugs at deaths that would spark national crises elsewhere. We’ve been conditioned to accept lower standards through a systematic propaganda campaign that conflates criticism of police with opposition to public safety, that treats accountability as anti-cop bias, that frames every demand for restraint as weakness in the face of threats.

This pathology didn’t emerge spontaneously. It was carefully constructed through decades of policy choices, media narratives, and cultural conditioning.

Start with the militarization of American policing. When we equip local police departments with armored vehicles, automatic weapons, and training that emphasizes “warrior mentality” over community service, we shouldn’t be surprised when they treat citizens as enemy combatants. The weapons don’t just kill—they shape psychology. Officers trained to see lethal threats everywhere will escalate situations until their fears materialize, then cite the crisis they created as proof they were right all along.

Add qualified immunity, which shields officers from accountability for all but the most egregious violations. When cops know they can kill with minimal consequences – perhaps a paid administrative leave, perhaps a transfer to another department – the incentive structure actively encourages lethal force. Why take the time to de-escalate when you can shoot and face no meaningful punishment?

Layer on media narratives that frame every police encounter as life-or-death drama, every person killed as a “dangerous criminal,” every protest as a riot. Decades of “copaganda” shows like Law & Order have trained Americans to identify with the badge, to experience every limit on police power as a personal threat, to see civil liberties as obstacles to justice rather than its foundation.

The result is a culture of learned helplessness and moral resignation. We accept as inevitable what other democracies consider intolerable.

In Sweden, police are trained to treat lethal force as a genuine last resort. De-escalation is mandatory. Firing at vehicles is extraordinarily rare. Officers face real investigation and prosecution when force is unjustified. The result? Dramatically fewer police killings – not chaos, not crime spikes, but a society that manages to maintain order without treating human life as disposable.

American culture shrugs at deaths that would spark national crises elsewhere. We’ve been conditioned to accept lower standards through a systematic propaganda campaign that conflates criticism of police with opposition to public safety, that treats accountability as anti-cop bias, that frames every demand for restraint as weakness in the face of threats.

The Legal Theater of Justification

The excuses marshaled to defend Renee Good’s killing follow a familiar script, designed to create the appearance of legal justification where none exists.

“The car is a deadly weapon.”

Only if it’s being used as one. A vehicle moving away at low speed from an agent with space to step aside does not present an imminent threat. DOJ policy is explicit: firearms may not be discharged at moving vehicles unless the vehicle threatens death or serious injury and no other reasonable means of defense exist, including moving out of the path. The agent walked in front of the vehicle, then stepped aside while firing. He created the “danger,” had space to disengage, and shot anyway. Self-defense does not apply.

“Split-second decisions.”

Use-of-force policy exists precisely for fast moments. Training instructs officers to create space, move laterally, use cover, and avoid shooting at moving vehicles except to stop an immediate threat. If the officer had time to stand, aim, and fire from the flank, he had time to step back and disengage. Speed is not a license for killing – it’s a reason for restraint. Professionals in genuinely dangerous occupations make split-second decisions without killing people all the time.

“Failure to comply.”

Even conceding non-compliance, lethal force requires an imminent threat under Graham v. Connor and DHS policy. The video shows her SUV moving away from the officer, who simply steps aside. Mere resistance, obstruction, or failure to follow orders never justifies killing someone. If it did, every traffic stop could end in execution.

“Officer safety comes first.”

This slogan has become a blank check for violence. Officer safety is protected by tactics, not bullets. Do not walk in front of a running vehicle. Do not escalate a calm situation just because you are being heckled. Use calm language to reduce panic. Once the vehicle was in motion, the officer could step aside (he did) and reassess. Every option short of gunfire was available to an officer not pinned, not dragged, and not struck.

“He feared for his life.”

Fear is a terribly pathetic excuse for officers supposedly trained to behave professionally under stressful situations. I saw an apt comment from a woman who remarked, “If I shot a man in the head every time I’ve felt afraid, the streets would be lined with bodies.”

“We have to back our agents.”

Accountability is how you back them. Lowering the bar for deadly force endangers officers by teaching bad tactics and eroding public trust. The standard must be higher for the person with state power and a gun, not lower. Every unjustified killing makes the next officer’s job more dangerous by deepening the divide between law enforcement and the communities they’re supposed to serve.

None of these excuses are legal arguments – they’re narrative tricks designed to move the goalposts after someone is dead.

Bottom line: there was no imminent threat, no pinned officer, a vehicle moving away, and ample alternatives.

The justification for lethal force fails necessity, proportionality, and last-resort tests.

The excuses marshaled to defend Renee Good’s killing follow a familiar script, designed to create the appearance of legal justification where none exists.

“The car is a deadly weapon.”

Only if it’s being used as one. A vehicle moving away at low speed from an agent with space to step aside does not present an imminent threat. DOJ policy is explicit: firearms may not be discharged at moving vehicles unless the vehicle threatens death or serious injury and no other reasonable means of defense exist, including moving out of the path. The agent walked in front of the vehicle, then stepped aside while firing. He created the “danger,” had space to disengage, and shot anyway. Self-defense does not apply.

“Split-second decisions.”

Use-of-force policy exists precisely for fast moments. Training instructs officers to create space, move laterally, use cover, and avoid shooting at moving vehicles except to stop an immediate threat. If the officer had time to stand, aim, and fire from the flank, he had time to step back and disengage. Speed is not a license for killing – it’s a reason for restraint. Professionals in genuinely dangerous occupations make split-second decisions without killing people all the time.

“Failure to comply.”

Even conceding non-compliance, lethal force requires an imminent threat under Graham v. Connor and DHS policy. The video shows her SUV moving away from the officer, who simply steps aside. Mere resistance, obstruction, or failure to follow orders never justifies killing someone. If it did, every traffic stop could end in execution.

“Officer safety comes first.”

This slogan has become a blank check for violence. Officer safety is protected by tactics, not bullets. Do not walk in front of a running vehicle. Do not escalate a calm situation just because you are being heckled. Use calm language to reduce panic. Once the vehicle was in motion, the officer could step aside (he did) and reassess. Every option short of gunfire was available to an officer not pinned, not dragged, and not struck.

“He feared for his life.”

Fear is a terribly pathetic excuse for officers supposedly trained to behave professionally under stressful situations. I saw an apt comment from a woman who remarked, “If I shot a man in the head every time I’ve felt afraid, the streets would be lined with bodies.”

“We have to back our agents.”

Accountability is how you back them. Lowering the bar for deadly force endangers officers by teaching bad tactics and eroding public trust. The standard must be higher for the person with state power and a gun, not lower. Every unjustified killing makes the next officer’s job more dangerous by deepening the divide between law enforcement and the communities they’re supposed to serve.

None of these excuses are legal arguments – they’re narrative tricks designed to move the goalposts after someone is dead.

Bottom line: there was no imminent threat, no pinned officer, a vehicle moving away, and ample alternatives.

The justification for lethal force fails necessity, proportionality, and last-resort tests.

What We’re Really Defending

When someone rushes to justify clearly excessive force, they’re not really defending that specific officer’s split-second decision. They’re defending an entire worldview – one where authority is sacred, where questioning power is the real crime, where the “wrong kind of people” stepping out of line deserve whatever they get.

This worldview is not compatible with democracy. Democracy requires the capacity to challenge power, to resist unjust policies, to document and expose misconduct. When people are conditioned to reflexively side with the badge, to treat every limit on state violence as dangerous, to experience pleasure when protesters, legal observers, or anyone who “doesn’t comply” gets hurt or killed, they’re being trained to act like obedient subjects, not citizens.

The sickest element is the glee. Not grudging acceptance or tragic necessity, but celebration. The comments sections I’ve witnessed these past 48 hours reveal people who aren’t reluctantly accepting “a tough but necessary call” – they’re enjoying it. They experience the killing as entertainment, as righteous retribution, as satisfying proof that “our side” has the power and will to dominate “theirs.”

This is the psychology of fascism, and it doesn’t require jackboots or swastikas. It just requires enough people who have learned to derive pleasure from watching the state hurt the right people.

When someone rushes to justify clearly excessive force, they’re not really defending that specific officer’s split-second decision. They’re defending an entire worldview – one where authority is sacred, where questioning power is the real crime, where the “wrong kind of people” stepping out of line deserve whatever they get.

This worldview is not compatible with democracy. Democracy requires the capacity to challenge power, to resist unjust policies, to document and expose misconduct. When people are conditioned to reflexively side with the badge, to treat every limit on state violence as dangerous, to experience pleasure when protesters, legal observers, or anyone who “doesn’t comply” gets hurt or killed, they’re being trained to act like obedient subjects, not citizens.

The sickest element is the glee. Not grudging acceptance or tragic necessity, but celebration. The comments sections I’ve witnessed these past 48 hours reveal people who aren’t reluctantly accepting “a tough but necessary call” – they’re enjoying it. They experience the killing as entertainment, as righteous retribution, as satisfying proof that “our side” has the power and will to dominate “theirs.”

This is the psychology of fascism, and it doesn’t require jackboots or swastikas. It just requires enough people who have learned to derive pleasure from watching the state hurt the right people.

The Question That Matters

When someone tries to deflect criticism of a clearly unjustified killing by searching for hypocrisy – “But did you condemn mockery on the other side?” – they’re engaging in a familiar evasion. Whether any individual critic is perfectly consistent has nothing to do with whether this specific killing was excessive, criminal, and should never have happened.

But let’s be clear: as a student of Thich Nhat Hanh’s teachings on compassion and nonviolence, I opposed Luigi’s assassination of UnitedHealthcare’s CEO. When Charlie Kirk was assassinated, I condemned his killing without qualification, grounded in a philosophy that refuses to dehumanize our political opponents.

Yes, revelry and jokes about Charlie Kirk’s death disturbed me too—they reflect the same slide toward conditional empathy that corrodes a society’s moral foundation. But for every finger pointed at isolated reactions on the left, three point back at the systematic celebration of violence on the right: from the gleeful reactions to George Floyd’s murder to the countless MAGA supporters cheering the killing of 80+ victims at sea by Pete Hegseth, which legal experts called war crimes, murder or both. Even White House, DHS, and other official social media accounts now openly post memes mocking their enemies.

But consistency is beside the point. The real issue is what kind of society we’re building.

What kind of culture reflexively excuses excessive lethal force by police or our government at every turn?

Those in the comments hunting for hypocrisy would do well to turn their questions inward: what am I doing to make this world a more compassionate and humane place for our children to inherit?

What am I doing?

What’s my role?

Am I living in service to life and human dignity for all? Am I challenging illegitimate abuses of power, or serving it?

When you see footage of someone being killed by agents of the state, and your first impulse is to search for reasons why they deserved it, you need to examine what has happened to your moral compass. When you type “FAFO” and get a little dopamine hit, you have crossed a line that separates civilization from barbarism.

When someone tries to deflect criticism of a clearly unjustified killing by searching for hypocrisy – “But did you condemn mockery on the other side?” – they’re engaging in a familiar evasion. Whether any individual critic is perfectly consistent has nothing to do with whether this specific killing was excessive, criminal, and should never have happened.

But let’s be clear: as a student of Thich Nhat Hanh’s teachings on compassion and nonviolence, I opposed Luigi’s assassination of UnitedHealthcare’s CEO. When Charlie Kirk was assassinated, I condemned his killing without qualification, grounded in a philosophy that refuses to dehumanize our political opponents.

Yes, revelry and jokes about Charlie Kirk’s death disturbed me too—they reflect the same slide toward conditional empathy that corrodes a society’s moral foundation. But for every finger pointed at isolated reactions on the left, three point back at the systematic celebration of violence on the right: from the gleeful reactions to George Floyd’s murder to the countless MAGA supporters cheering the killing of 80+ victims at sea by Pete Hegseth, which legal experts called war crimes, murder or both. Even White House, DHS, and other official social media accounts now openly post memes mocking their enemies.

But consistency is beside the point. The real issue is what kind of society we’re building.

What kind of culture reflexively excuses excessive lethal force by police or our government at every turn?

Those in the comments hunting for hypocrisy would do well to turn their questions inward: what am I doing to make this world a more compassionate and humane place for our children to inherit?

What am I doing?

What’s my role?

Am I living in service to life and human dignity for all? Am I challenging illegitimate abuses of power, or serving it?

When you see footage of someone being killed by agents of the state, and your first impulse is to search for reasons why they deserved it, you need to examine what has happened to your moral compass. When you type “FAFO” and get a little dopamine hit, you have crossed a line that separates civilization from barbarism.

The Alternative We Refuse to Imagine

The most pernicious lie embedded in these defenses is that this is simply how things must be. That police work is so dangerous, we can’t expect better outcomes. That questioning lethal force endangers officers and invites chaos, or is “anti-American.”

This is learned helplessness and nationalist ideology disguised as realism. Other democracies prove it’s a lie.

Police in England, Germany, Japan, and Scandinavia face dangerous situations without killing people at anywhere near American rates. They manage this not because their citizens are more compliant or their criminals less dangerous, but because their training, policies, and culture prioritize de-escalation over dominance, view lethal force as a genuine last resort rather than a routine tool, and hold officers accountable when they exceed those boundaries.

The argument that “American gun culture makes this impossible” ignores that the most egregious police killings occur in situations that don’t involve suspects with guns. George Floyd wasn’t armed. Eric Garner wasn’t armed. Tamir Rice had a toy gun and was killed within two seconds. Renee Good was in a slowly moving vehicle. The vast majority of these killings are tactical failures, not unavoidable shootouts.

The argument that “police need better training” also miss the point entirely. Reports indicate Renee Good’s killer had extensive training. The problem isn’t a skills deficit—it’s a culture of violence. It’s fascism wearing a badge.

This becomes undeniable when you watch the video where you can hear an ICE officer calling Good a “fucking bitch” after she was shot, lying bleeding in her vehicle. When they refused to let her get medical help as she died, an officer replied, “I don’t care.” That’s not an undertrained officer making a tragic mistake. That’s an officer who wanted her dead, and who felt entitled to kill her because his feelings were hurt moments before.

Any honest police officer will tell you they have the capacity to engage, contain, and disengage without killing people. Other democracies prove this every day. American cops choose not to because they operate within a culture that treats such deaths not as failures but as features—acceptable, even desirable demonstrations of power. This isn’t about maintaining public safety. It’s about maintaining a specific kind of order: one where any challenge to authority, no matter how minor, no matter how lawful, is met with overwhelming force. Where the state’s monopoly on violence must be demonstrated repeatedly, viscerally, lethally, to remind everyone who holds power and what happens when you forget your place.

The most pernicious lie embedded in these defenses is that this is simply how things must be. That police work is so dangerous, we can’t expect better outcomes. That questioning lethal force endangers officers and invites chaos, or is “anti-American.”

This is learned helplessness and nationalist ideology disguised as realism. Other democracies prove it’s a lie.

Police in England, Germany, Japan, and Scandinavia face dangerous situations without killing people at anywhere near American rates. They manage this not because their citizens are more compliant or their criminals less dangerous, but because their training, policies, and culture prioritize de-escalation over dominance, view lethal force as a genuine last resort rather than a routine tool, and hold officers accountable when they exceed those boundaries.

The argument that “American gun culture makes this impossible” ignores that the most egregious police killings occur in situations that don’t involve suspects with guns. George Floyd wasn’t armed. Eric Garner wasn’t armed. Tamir Rice had a toy gun and was killed within two seconds. Renee Good was in a slowly moving vehicle. The vast majority of these killings are tactical failures, not unavoidable shootouts.

The argument that “police need better training” also miss the point entirely. Reports indicate Renee Good’s killer had extensive training. The problem isn’t a skills deficit—it’s a culture of violence. It’s fascism wearing a badge.

This becomes undeniable when you watch the video where you can hear an ICE officer calling Good a “fucking bitch” after she was shot, lying bleeding in her vehicle. When they refused to let her get medical help as she died, an officer replied, “I don’t care.” That’s not an undertrained officer making a tragic mistake. That’s an officer who wanted her dead, and who felt entitled to kill her because his feelings were hurt moments before.

Any honest police officer will tell you they have the capacity to engage, contain, and disengage without killing people. Other democracies prove this every day. American cops choose not to because they operate within a culture that treats such deaths not as failures but as features—acceptable, even desirable demonstrations of power. This isn’t about maintaining public safety. It’s about maintaining a specific kind of order: one where any challenge to authority, no matter how minor, no matter how lawful, is met with overwhelming force. Where the state’s monopoly on violence must be demonstrated repeatedly, viscerally, lethally, to remind everyone who holds power and what happens when you forget your place.

Resisting the Sickness

Part of staying human in a sick culture is resisting “the way it is” and demanding better. It means refusing to let your moral intuitions be overridden by narratives designed to justify the unjustifiable. It means recognizing that the reflex to defend state violence isn’t driven by law or evidence – it’s cultural conditioning.

When you see footage that disturbs you, that conflicts with official narratives claiming “imminent threat,” “domestic terrorist,” or “officer safety,” trust your eyes. Trust your moral sense that something is deeply wrong when the state kills someone who could have been easily addressed without lethal force.

When you encounter people celebrating that death, understand what you’re witnessing: not legitimate debate about a difficult judgment call, but the pathological pleasure of watching power crush someone who stepped out of line. These people are not guardians of public safety. They are apologists for bloodletting.

To anyone who truly believes what you saw warrants execution: you have absolutely zero respect for the sacredness of life and you should be considered a danger to the people around you.

That’s not hyperbole. A person who cheers the state’s right to kill someone for imperfect compliance has revealed something profound about their character. They have demonstrated that they value obedience to authority above human life. But that absence of empathy doesn’t confine itself to strangers on screens—it shapes how they treat everyone around them.

This mindset, if it’s not obvious, is not a foundation for a free society. It’s the psychology that enables atrocity – not just through deliberate malice, but through learned indifference to suffering when it happens to people we’ve been conditioned to see as “other.”

Part of staying human in a sick culture is resisting “the way it is” and demanding better. It means refusing to let your moral intuitions be overridden by narratives designed to justify the unjustifiable. It means recognizing that the reflex to defend state violence isn’t driven by law or evidence – it’s cultural conditioning.

When you see footage that disturbs you, that conflicts with official narratives claiming “imminent threat,” “domestic terrorist,” or “officer safety,” trust your eyes. Trust your moral sense that something is deeply wrong when the state kills someone who could have been easily addressed without lethal force.

When you encounter people celebrating that death, understand what you’re witnessing: not legitimate debate about a difficult judgment call, but the pathological pleasure of watching power crush someone who stepped out of line. These people are not guardians of public safety. They are apologists for bloodletting.

To anyone who truly believes what you saw warrants execution: you have absolutely zero respect for the sacredness of life and you should be considered a danger to the people around you.

That’s not hyperbole. A person who cheers the state’s right to kill someone for imperfect compliance has revealed something profound about their character. They have demonstrated that they value obedience to authority above human life. But that absence of empathy doesn’t confine itself to strangers on screens—it shapes how they treat everyone around them.

This mindset, if it’s not obvious, is not a foundation for a free society. It’s the psychology that enables atrocity – not just through deliberate malice, but through learned indifference to suffering when it happens to people we’ve been conditioned to see as “other.”

What Actually Needs to Change

The solutions aren’t complicated. Other democracies have already implemented them. The question is whether we have the political will to dismantle systems that serve power at the expense of human life.

Enforce the policies we already have. ICE’s own guidelines discourage shooting at moving vehicles. The officer who killed Renee Good violated them. But policies mean nothing without enforcement, investigation, and prosecution. Officers who violate use-of-force standards must face criminal charges, not paid leave and internal whitewashing.

End qualified immunity. When cops can kill with minimal consequences—perhaps paid leave, perhaps a transfer—the incentive structure actively encourages lethal force. Officers must face real civil liability for rights violations. If doctors can be sued for malpractice, cops should be sued for killing people who posed no threat.

Root out the infiltration. The FBI has warned for decades about white supremacists and far-right extremists infiltrating law enforcement. Any officer with ties to extremist groups must be immediately terminated and barred from law enforcement. Any agency that refuses to purge these elements should lose federal funding.

Abolish ICE. An agency whose founding purpose was mass deportation, whose culture celebrates cruelty, whose agents operate with near-total impunity, cannot be reformed. It must be dismantled. Immigration enforcement existed before ICE and can exist after—but not through an organization that has become a magnet for extremists and an incubator for violence.

Spiritual self-defense. We must retain our humanity in the face of relentless propaganda training us to deaden our hearts and minds. The machinery of justification isn’t just institutional—it’s psychological. Every “FAFO” comment, every reflexive defense of obvious brutality, every search for some detail that makes a killing seem reasonable represents a small victory for forces that want us compliant, obedient, and numb to state violence.

They need us desensitized. They need us asking the wrong questions. They need us identifying with the badge instead of recognizing ourselves in the person being killed. Resisting this requires conscious effort: trusting your moral intuitions when they conflict with official narratives, recognizing that the reflex to defend state violence is cultural conditioning, not evidence-based reasoning. Your capacity for moral horror at unnecessary death is not naivete—it’s the last line of defense against normalized barbarism. Protect it fiercely.

The solutions aren’t complicated. Other democracies have already implemented them. The question is whether we have the political will to dismantle systems that serve power at the expense of human life.

Enforce the policies we already have. ICE’s own guidelines discourage shooting at moving vehicles. The officer who killed Renee Good violated them. But policies mean nothing without enforcement, investigation, and prosecution. Officers who violate use-of-force standards must face criminal charges, not paid leave and internal whitewashing.

End qualified immunity. When cops can kill with minimal consequences—perhaps paid leave, perhaps a transfer—the incentive structure actively encourages lethal force. Officers must face real civil liability for rights violations. If doctors can be sued for malpractice, cops should be sued for killing people who posed no threat.

Root out the infiltration. The FBI has warned for decades about white supremacists and far-right extremists infiltrating law enforcement. Any officer with ties to extremist groups must be immediately terminated and barred from law enforcement. Any agency that refuses to purge these elements should lose federal funding.

Abolish ICE. An agency whose founding purpose was mass deportation, whose culture celebrates cruelty, whose agents operate with near-total impunity, cannot be reformed. It must be dismantled. Immigration enforcement existed before ICE and can exist after—but not through an organization that has become a magnet for extremists and an incubator for violence.

Spiritual self-defense. We must retain our humanity in the face of relentless propaganda training us to deaden our hearts and minds. The machinery of justification isn’t just institutional—it’s psychological. Every “FAFO” comment, every reflexive defense of obvious brutality, every search for some detail that makes a killing seem reasonable represents a small victory for forces that want us compliant, obedient, and numb to state violence.

They need us desensitized. They need us asking the wrong questions. They need us identifying with the badge instead of recognizing ourselves in the person being killed. Resisting this requires conscious effort: trusting your moral intuitions when they conflict with official narratives, recognizing that the reflex to defend state violence is cultural conditioning, not evidence-based reasoning. Your capacity for moral horror at unnecessary death is not naivete—it’s the last line of defense against normalized barbarism. Protect it fiercely.

Choose Humanity

Choose to retain your capacity for moral horror. Choose to trust your eyes when they show you something wrong, even when authority insists you’re seeing it incorrectly. Choose to ask why the officer escalated rather than why she didn’t comply. Choose to recognize that her life had inherent worth regardless of her choices in those final seconds.

Choose to build a society where we hold power accountable rather than rush to excuse its failures. Where we demand de-escalation and restraint from those we grant badges and guns. Where we respond to unnecessary death with outrage and action rather than manufactured justifications and victim-blaming.

That choice—renewed daily in how we respond to each new killing, each new justification, each new celebration of cruelty—is what determines whether we’re building a democracy or a death cult.

There is no middle ground. Either human life is sacred, or it’s conditionally valuable based on compliance with authority. Either we hold power to the highest standards, or we grant it permission to kill anyone who inconveniences it.

Renee Good’s last words before the escalation were “It’s fine, dude. I’m not mad at you.” She was calm. She was kind. And then an agent created panic, and another agent killed her for the fear they manufactured.

If that doesn’t fill you with rage and determination to demand better, check your pulse. Reach out to friends and family. You might have already deadened something essential to being human.

The machinery of propaganda wants you numb, compliant, and willing to accept that “this is just how things are.” Resist that. Fiercely. Your humanity depends on it. So does any possibility of building a society worthy of our children to inherit.

Choose to retain your capacity for moral horror. Choose to trust your eyes when they show you something wrong, even when authority insists you’re seeing it incorrectly. Choose to ask why the officer escalated rather than why she didn’t comply. Choose to recognize that her life had inherent worth regardless of her choices in those final seconds.

Choose to build a society where we hold power accountable rather than rush to excuse its failures. Where we demand de-escalation and restraint from those we grant badges and guns. Where we respond to unnecessary death with outrage and action rather than manufactured justifications and victim-blaming.

That choice—renewed daily in how we respond to each new killing, each new justification, each new celebration of cruelty—is what determines whether we’re building a democracy or a death cult.

There is no middle ground. Either human life is sacred, or it’s conditionally valuable based on compliance with authority. Either we hold power to the highest standards, or we grant it permission to kill anyone who inconveniences it.

Renee Good’s last words before the escalation were “It’s fine, dude. I’m not mad at you.” She was calm. She was kind. And then an agent created panic, and another agent killed her for the fear they manufactured.

If that doesn’t fill you with rage and determination to demand better, check your pulse. Reach out to friends and family. You might have already deadened something essential to being human.

The machinery of propaganda wants you numb, compliant, and willing to accept that “this is just how things are.” Resist that. Fiercely. Your humanity depends on it. So does any possibility of building a society worthy of our children to inherit.