Authors from Carl Jung to Aldous Huxley and Susan Blackmore explore the deep mysteries of what it means to be a person

Charles Foster

Wed 29 Sep 2021 12.00 BST

Do you know what sort of animal you are? It’s rather important to know. If you call yourself a humanist, for instance, don’t you need some idea of what a human is so that you can make sure your behaviour accords with your ethics? If you think that humans are just a little lower than the angels, as the Judaeo-Christian tradition says, shouldn’t you know how much lower, so you can be appropriately aspirational but not frustrated or cocky?

And then there’s the problem of personal identity. When you say “I love you”, or “I‘m afraid”, how confident are you about wielding that mighty and mysterious pronoun? Are you as confident as modern neuroscientists that “you” are just the chemical events that happen in your brain? Does that explanation satisfy you?

I expect, if you’re asked what “you” are, part of your answer would involve saying that you were human. So we’re back to the first problem.

All these questions worried me sick. I thought the best way to address them was to go on a journey back through the human story, pausing and immersing myself, using a kind of archaeological method acting, in three pivotal ages – ages when seismic shifts in human self-understanding occurred. These were the Upper Palaeolithic (the vast majority of our history: we’re still really hunter-gatherers, even if we wear a suit and sit slumped in front of a laptop), the Neolithic (when we caged the natural world and ourselves), and the Enlightenment (when the universe, previously seen as fizzing with consciousness, was declared to be merely a machine).

I wrote a book about this journey. It’s called Being a Human. I’m now a bit less queasy than I was about saying “I love you”. Though many mysteries have deepened and multiplied, I think I’ve got some idea of the sort of animal you are and I am.

Here are a few of the books I took along the road. Some were congenial; some infuriating.

1. The Matter With Things by Iain McGilchrist

A massive book and a massive achievement. A follow-up to McGilchrist’s epic The Master and His Emissary, which explored the way in which our perception of the world, and of ourselves, is influenced by – or is – the conversation or stand-off between the two cerebral hemispheres. The Matter With Things is a devastating assault on the view that there is only matter (whatever that is), and that consciousness can emerge from a conglomeration of unconscious units.

2. Scatterlings by Martin Shaw

Very few books about the wild are wild, and so very few are worthy of their subject. This one is. It’s a tale of how to be claimed by a place, and about how we’re dying because (being stories ourselves) we need good stories as we need clean air, and yet we’re offered only the tawdry stories of material reductionism and the free market – stories which literally de-mean us. Shaw knows how stories seep out of the earth. The earth, like everything, has agency, and it wants us to audition for parts in its constantly evolving stories. What is a thriving human? For Shaw, as for Upper Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers, it’s something that has a human body, which defines its position by reference to everything else in the world rather than by reference to itself, and which gets a good part in the local story.

3. The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind by Julian Jaynes

Often parodied, seldom read, Jaynes argues that (for instance) the voices of the gods in the heads of the Homeric heroes were really the voices of one compartment of the mind, overheard by another, and that true modern consciousness arose when the wall between those compartments dissolved. Though there’s too much dissonance with the archaeological record to convince me, it’s a fascinating thesis, supported by a dizzying range of references, and Jaynes is a brave and swashbuckling writer.

4. The Hidden Spring by Mark Solms

The market is awash with books expressing blithe optimism that neuroscience is about to tell us what consciousness is, why it’s there, and how it is generated. Solms is with the mainstream materialist cohort in thinking that consciousness is a function of brain activity. I’d prefer to say that brains receive, process, and perhaps broadcast consciousness. But Solms’s book stands out from the herd, marked by fitting wonderment and doubt.

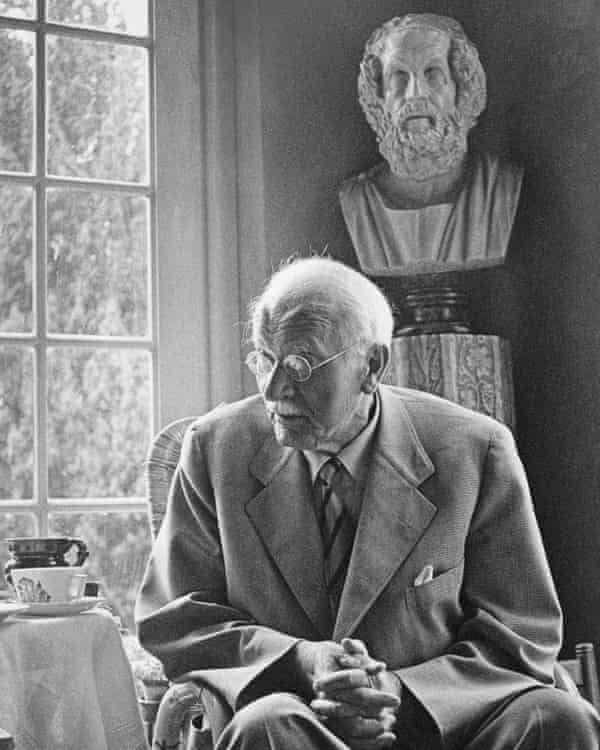

5. Modern Man in Search of a Soul by Carl Jung

Our consciousness is relatively uninteresting and insignificant compared with our unconscious. Most of what “I” really am and what “I” actually do wells up from far below the surface. Jung is one of the great explorers of the dark but sovereign subconscious. You’ll bump into his archetypes if you dream diligently, fast long enough, or sit down in a winter wood and stare into the middle distance.

6. Nine-Headed Dragon River by Peter Matthiessen

Matthiessen, best known for The Snow Leopard, was an advanced Zen practitioner. This book contains some of his meditation diaries. They’re full of vertiginous worked examples, showing how to watch your own mind working.

7. Consciousness: A Very Short Introduction by Susan Blackmore

The most accessible overview of the subject, bracingly written. She thinks my views are credulous and atavistic, and says so splendidly and compellingly. Ponder her question: “What were you conscious of a moment ago?”’'

8. Breaking Convention: Essays on Psychedelic Consciousness

One of a set of proceedings of a biennial conference focusing on the academic study of psychedelics and related subjects such as shamanism and out of body and near-death experiences. Tectonic scientific progress is made by looking at the outliers – the evidence that doesn’t fit with your comforting old preconceptions. These studies do that.

9. Beyond Words by Carl Safina

Moving accounts of the reasons to suppose that various non-humans, including orcas, wolves and elephants, have emotions and a type of consciousness akin to ours. If they are conscious, why shouldn’t stones be conscious too?

10. The Doors of Perception by Aldous Huxley

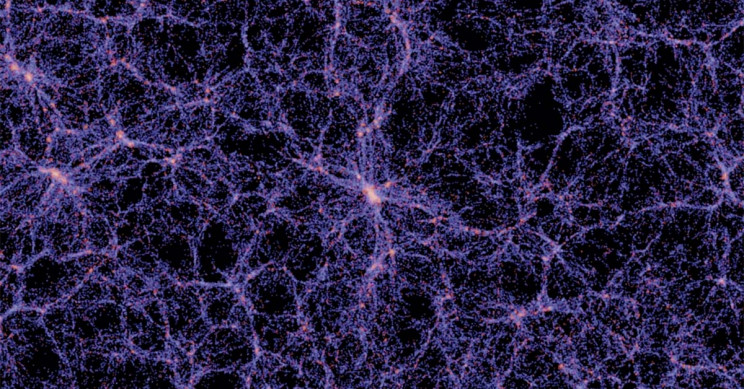

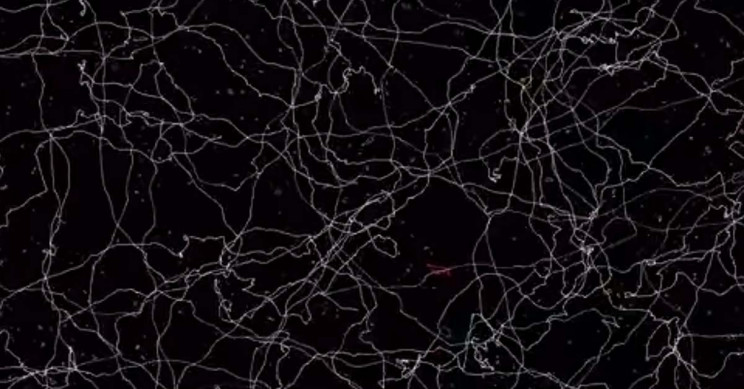

Based on his experiences of taking the hallucinogen mescaline. Huxley concluded that the brain acted like a reducing valve, slowing down the influx of data into our brains to a manageable dribble. We may be drawing conclusions about the universe on the basis of a tiny fraction of the available information. We might be misreading it radically. It has recently been shown that human neural networks can process 11 dimensions. We usually use only four. We’re wired up for much, much more reality than we think.

Being a Human by Charles Foster is published by Profile in the UK and Metropolitan in the US.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/69926085/hudf_hst_6200x6200_print.0.jpeg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22884302/9682953582_7029d9580d_b.jpeg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22887154/timeline.jpeg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22885255/niac2020_bandyopadhyay.jpeg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6030221/gravitywaves.gif)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22885277/slide_09_A1_LISA_orbits2.2021_09_28_14_50_25.gif)