In 1670, the Virginia assembly, comprising some of the colony’s most successful and powerful men, forbade free Negroes and Indians to own Christian (that is to say, white) servants. In 1676, the assembly made it legal to enslave Indians. From 1680 on, white Christians were free to give "any negroe or other slave" who dare to lift his hand in opposition to a Christian 30 lashes on the bare back. In 1705, masters were forbidden to ‘whip a Christian white servant naked." Nakedness was for brutes, the uncivil, the non-Christian. That same year, all property – "horses, cattle, and hogs" – was confiscated from slaves and sold by church wardens for the benefit of poor whites. By means of such acts, the tobacco planters and ruling elite of Virginia raised the legal status of lower-class whites relative to that of Negroes and Indians, whether free, servant, or slave.

The legislators also raised the status of white servants, workers, and the white poor in relations to their masters and other white superiors. Until then the European indentured servants had lived and worked under the same conditions as the African slaves, the chief difference in their status being that the Europeans’ servitude was contracted for a specified period whereas the slaves, and their progeny, served for life. In 1705, the assembly required masters to provide white servants at the end of their indentureship with corn, money, a gun, clothing, and 50 acres of land. The poll tax was also reduced. As a result of these legally sanctioned changes in poor whites’ economic position, they gained legal, political, emotional, social, and financial status that depended directly on the concomitant degradation of Indians and Negroes.

By means of the race laws, Virginia’s ruling class systematically gave their blessing to lower-class whites, whom they nevertheless considered "the scruff and scum of England" and who, free no in the colonies after indentured servitude, were thought of as the rabble of Virginia. Social historian Edmund Morgan reminds us how radical the race laws were when he notes that the

Stereotypes of the poor expressed so often in England during the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were often identical with the descriptions of blacks expressed in colonies dependent upon slave labor, even to the extent of intimating the subhumanity of both: the [white] poor were ‘the vile and brutish part of mankind’; [blacks] ‘a brutish sort of people.’ In the eyes of unpoor Englishmen, the poor bore many of the marks of an alien race.

These descriptions were consistent with a contemporary usage of race denoting something like what we mean by class today. As cultural scholar Ann Laura Stoler notes in her book Race and the Education of Desire, the "race" of the rising English industrial class pertained not to their color or physiognomy but to their bourgeois class status, mores, and manners. Accordingly, racial superiority, and thus the right to rule, came to be equated with middle-class respectability. The poor, by definition, could never belong to this new bourgeois race.

Morgan writes that some of the ‘alien," bedraggled and penniless Englishmen and women were shipped to Virginia, and

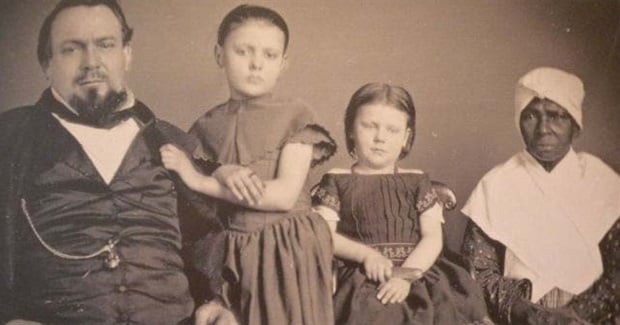

When their masters began to place people of another color in the fields beside them, the unfamiliar appearance of the newcomers may well have struck them as only skin deep. There are hints that the two despised groups initially saw each other as sharing the same predicament. It was common, for example, for servants and slaves to run away together, steal hogs together, get drunk together. It was not uncommon for them to make love together.

African-born slaves and European-born indentured servants collaborated throughout the Anglo-American colonies. In the British West Indies, for example, legislation was passed in 1701 that forbade the importation of Irish Catholics, and subsequently of any Europeans, to the island of Nevis because European servants had combined there with African slaves to rebel against the ruling elite. The Virginia race laws by which plantation masters elevated the racial status of their white servants, workers, and other "rabble" were enacted for the exact same reasons as the Nevis race laws.

To understand this fully requires attention to the new role slavery began to play in Virginia as the 17th century wore on. By 1660, it had become more profitable for the labor barons to buy slaves rather than the labor of indentured servants. A host of reasons explain this shift, including a dwindling pool of prospects for indentured servitude and a decline in mortality from diseases in the colony, which made slaves, although twice the price of indentured servants, a better long-term investment. Because slaves and their progeny served for life, the time and work extracted from them would more than repay the added cost. To increase slaves’ productivity, masters had only to increase the severity of beatings and maimings, meanwhile enacting laws to protect themselves from prosecution for the inadvertent killings that might result.

This new setup, however, required a new strategy for social control, for the natural class affinities between indentured servants and enslaved ones presented a danger to the masters. Until 1660, indentured servants outnumbered slaves on the Virginia tobacco plantations. They were kept in separate servant quarters, supervised by overseers, and whipped as a means of "correction." Like their 18th century slave counterparts, they were also underfed and underclothed. In response, they sometimes ran away but rarely, if ever, rebelled as a class.

As freedmen, however, they did rebel. Led by a well-born Englishman named Nathaniel Bacon, a government official who ironically held wealthy Virginians in contempt because of their "vile" (lower-class) beginnings, the freedmen first slaughtered Indians and then turned their guns on the ruling elite. The rebels were rankled by unfair taxes, legislators’ greed, and land use regulations that relegated most of them to the status of landless workers for hire. This 1676 "Bacon Rebellion" did not end before Jamestown was burned to the ground, Bacon died, and the English intervened militarily. Last to surrender was a group of 80 Negroes and 20 English servants.

With a swelling slave population, the masters faced the prospect of white freedmen with disappointed hopes joining forces with slaves of desperate hope to mount ever more virulent rebellions. The elites’ race strategy decreased the probability of such class rebellions. The problem of how to redirect the "rabble" so that they would not bond with slaves was resolved through the sinister design of racialization. Writes Morgan, "The answer to the problem, obvious if unspoken and only gradually recognized, was racism, to separate dangerous free whites from dangerous slave blacks by a screen of racial contempt."

Racial contempt would function as a wall between poor whites and blacks, protecting masters and their slave-produced wealthy from both lower-class whites and slaves. At the same time, the new laws led the poor whites to identify with the ruling elite, an identification with an objective basis in fact – otherwise this divide and conquer class strategy would not have worked. Laws like the ones that gave white freedmen the right to whip a Negro slave but prevented white servants from being whipped while naked engendered a psychological allegiance to the elite through abuse: the right to abuse those below them and a constraint on the abuse meted out by those above them. Of course, this allegiance, and the laws that engendered it, did not protect the white servant from being beaten. The laws simply limited the abuse and thus, in the guise of a humane reform, actually maintained the legal sanction of violence against both the black and white servant and worker.

In addition to their marginal privileges

vis-à-vis punishment, poor whites acquired new political and social advantage by means of these new laws, along with the legislated right to feel superior to all nonwhites. A quota of "deficiency laws" was established to link white workers to black slaves, thus ensuring the stability of the race-based economic status quo. Historian Theodore Allen writes that these laws required plantation owners to "employ at least one ‘white’ for every so many ‘Negroes,’ the proportion varying from colony to colony and time to time, from one-to-twenty (Nevis, 1701) to one-to-four (Georgia, 1750)."Other laws urged slave owners to bar Negroes from trades in order to preserve those positions for "white" artisans. / 17 / The increasingly pervasive link between white work and the degraded condition of the black led white workers to accept the reality of – and necessity for – black slavery.

Not surprisingly, however, poor whites never became the economic equals of the elite. Though both groups’ economic status rose, the gap between the wealthy and poor widened as a result of slave productivity. Thus, poor whites’ belief that they now shared status and dignity with their social betters was largely illusory.

The new multi-class "white race" that emerged from the Virginia laws wasn’t biologically engineered but socially constructed, then. As Allen points out, the race laws and the racial contempt they generated not only severed ties of mutual interest and goodwill between European and African servants and workers, but they also provided the ruling elite with a "buffer" of poor whites between themselves and the slaves to keep blacks down and prevent both groups from challenging the rule of the elite. A. Leon Higgenbotham Jr., the former chief judge of the United States court of Appeals for the third Circuit, is right when he says the Virginia race laws, which were soon imitated throughout the colonies, were designed to "presume, protect, and defend the ideal of superiority of whites and the inferiority of blacks." But we must not forget that white racism was from the start a vehicle for classism; its primary goal was not to elevate a race but to denigrate a class. White racism was thus a means to an end, and the end was the defense of Virginia’s class structure and the further subjugation of the poor of all "racial" colors.

Interestingly, there was early resistance to these race laws by the newly whited lower classes. When, for example, the Virginia Assembly in 1691 outlawed mixed marriages and thus mulatto offspring ("that abominable mixture and spurious issue"), residents petitioned the assembly in 1699 "for the Repeale of the Act of Assembly, Against English people’s Marrying with Negroes Indians or Mulattoes." The petition, after internal legislative maneuvers, was ignored. During this same period, an Englishwoman named Ann Wall was arraigned by a county court and charged with "keeping company with a negro under pretense of marriage." She was convicted, bound with her two mulatto children to indentured service in another county, and told that if she ever returned to her home in Elizabeth City, she would be banished to Barbados.

Gradually, however, the new legislation began to influence both the class and racial perceptions of the "white" Virginians, as the memories of communal life and work shared by indentured Euro-American and enslaved African American workers were lost with the death of the first generations of Virginians. Thus, by 1825, free white laborers either emigrated to the West or festered in extraordinary poverty because their race pride prevented them from working alongside free Negroes. For example, in 1825, a petition circulated among citizens of Henrico County in Virginia asserted that "white [the free negro] re- / 18 / mained here … no white laborer will seek employment near him. Hence it is that in some of the richest counties east of the Blue Ridge the white population is stationary and in many others it is retrograde." Noting the pattern of white emigration from Virginia, Governor Smith in his 1847 message to the legislature said, "I venture the opinion that a larger emigration of our white laborers is produced by our free negroes than by the institution of slavery." Poor whites’ racial antipathy toward free Negro Virginians not only staved off political collaboration but further enriched the white employers, who preferred Negro freedmen over whites because they worked cheaper. Also, because they had no legal protections, they were totally subject to their employers’ wishes. As Governor Smith complained in 1848, free Negroes "perform a thousand little menial services to the exclusion of the white man. [They are] preferred by their employers because of the authority and control which they can exercise and frequently because of the ease and facility with which they can remunerate such services." Classism augmented by racism thus succeeded in disempowering the white Virginia lower classes, but these whites’ own racism further disempowered them by distracting them from the class exploitation that they shared with Negroes.

As W.E.B. Du Bois notes in his seminal work, Black Reconstruction in America: 1860-1880, the poor white man couldn’t conceive of himself as a laborer because of labor’s association with Negro toil. Rather, the poor white, if he aspired at all, aspired to become a planter and own "niggers." Accordingly, he transferred his hatred for the slave system to the Negro and by so doing stabilized the entire slave system as "overseer, slave driver and member of the patrol system. But above and beyond this role in maintaining the slave system, it fed his vanity because it associated [him] with the masters." The poor white’s association with the southern elite, however, was a one-way affair. As one observer noted, "For twenty years, I do not recollect ever to have seen or heard these non-slaveholding whites referred to by the Southern gentlemen as constituting any part of what they called the South."

The poor whites’ vanity was thus based on both fact and illusion. The fact pertained to the poor whites’ race. They did have the race privilege of not being slaves and legal rights as citizens because they were white. The illusion pertained to their class status. Their race made them think of themselves as planters and aristocrats, while their actual economic and social condition was dire. Only 25 percent of the poor whites were literate. Frederick L. Olmstead in his 1856 book A Journey to the Seaboard Slave States details their living conditions in the following description of a white backwoods settlement:

A wretched log hut or two are the only habitations in sight. Here reside, or rather take shelter, the miserable cultivators of the ground, or a still more destitute class who make a precarious living by peddling "lightwood" in the city…

These cabins … are dens of filth. The bed if there be a bed is a layer of something in the corner that defies scenting. If the bed is nasty, what of the floor? What of the whole enclosed space? What of the creatures themselves? Pough! Water in use as a purifier is unknown. Their faces are bedaubed with the muddy accumulation of weeks. They just give them a wipe when they see a stranger to take off the blackest dirt…. The poor wretches seem startled when you address them, and answer your questions cowering like culprits."

As for poor urban whites, he wrote:

I saw as much close packing, filth and squalor, in certain blocks inhabited by laboring whites in Charleston, as I have witnessed in any Northern town of its size; and greater evidences of brutality and ruffianly character, than I have ever happened to see, among an equal population of this class, before."

Clearly, then, the poor white masses, like the black slaves, were also racial victims of the upper class. The two exploited, racialized groups differed, however, in their degree of self-awareness. Virtually all slaves knew they were victims of white racism, while very few whites knew that they were, too.

A good example of the racial violence meted out to the whited lower classes by the ruling elite involved the voting eligibility requirements in the South. Here we find the white-on-white class conflict that interracial conflict was designed to obscure. As Du Bois observes, "most Southern state governments required a property qualification for the Governor, and in South Carolina," the minimum value of his financial worth was stipulated: $10,000. He adds, "In North Carolina, a man must own 50 acres to vote for a Senator." Thus in 1828, out of 250 votes in Wilmington, North Carolina, only 48 men could vote in senatorial elections.

The white southern elite also established the "extraordinary rule" of allowing slave owners to exercise the vote of all or at least three-fifths of their black slaves. This concentration of political power not only degraded, in theory, the personhood of people with African ancestry by counting many such persons as only three-fifths human, but it effectively disenfranchised virtually all white southerners except for the biggest slaveholders. And at the beginning of the Civil War, seven percent of white southerners owned almost three quarters (three million) of the slaves in this country. Thus, although the South had two million slaveholders in 1860, an oligarchy of 8,000 actually ruled the region, controlling the five million whites too poor to own slaves. The lower classes responded with self-contempt and blindness to such of their own class interests as went beyond their perceived racial interests as whites.

The psychological self-destruction entailed in poor whites’ celebration of race to the detriment of their own class interests takes us into the realm of lower-class white shame. The 1941 classic The Mind of the South, by the southern essayist and social critic W.J. Cash, gives us an intimate and detailed description of the hidden injury done to the southern Euro-American’s personality structure by the racialization of class issues described above.

Cash tersely assesses the psychological price paid by the southern Euro-American man of any class who defines himself as white: "a fundamental split in his psyche [resulting] from a sort of social schizophrenia." Those at the top believed they were as grand and aristocratic as the Virginians after who they modeled themselves. Backwater cotton planters thus imitated the Virginians in manner, dress, and comportment, but they could never, Cash argues, "endow their subconscious with the aristocrat’s experience, which is the aristocratic manner’s essential warrant. In their inmost being they carried nearly always, I think, an uneasy sensation of inadequacy for their role."

The common man also wrapped himself in class illusions that separated him from the actual experiences of his life. He actively embraced the idea that he was an aristocrat, identifying with the planter class through a glowing sense of participation in the common brotherhood of white men. The "ego-warming and ego-expanding distinction between the white man and the black" elevated this common white man, Cash argues,

to a position comparable to that of, say, the Doric knight of ancient Sparta. Not only was he not exploited directly, he was himself made by extension a member of the dominant class – was lodged solidly on a tremendous superiority, which, however much the blacks in the "big house" might sneer at him, and however much their masters might privately agree with them, he could never publicly lose. Come what might, he would always be a white man. And before that vast and capacious distinction, all others were foreshortened, dwarfed, and all but obliterated.

The grand outcome was the almost complete disappearance of economic and social forces on the part of the masses. One simply did not have to get on in this world in order to achieve security, independence, or value in one’s estimation and in that of one’s fellows.

This delusional "vast and capacious distinction," by blinding the white poor to their own class interests, reduced the common white man’s economic worth to naught. Writes Cash, "let him be stripped of this proto-Dorian rank and he would be left naked, a man without status." In effect, the emotional security lent by the hand of a fine gentleman on the common man’s shoulder in a friendly greeting became a substitute for economic security. Having shifted focus form class issues to racial feelings, the common white man, in effect, had been robbed of almost everything by his own racial "brothers."

Reproduced from: World: The Journal of the Unitarian Universalist Association. Vol. XII No: 4 (July/August 1998), pp. 14 –20)

Rev. Dr. Thandeka is the author of Learning to be White."No reader of Thandeka's book will ever be able to think about race in quite the same way again."

- John B. Cobb, Jr., The Claremont Graduate School

"No other study so fully demonstrates the origins of white identity in misery and defeat, as well as in power and privilege. Whiteness, Thandeka shows, is a shame which divides and afflicts whites as well as the nation."

- David Roediger, author of The Wages of Whiteness