Physicists from the University of California, Irvine (UCI) found never-before-seen "ghost particles", or neutrinos, in the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) during an experiment called FASER, a report from New Atlas reveals.

Neutrinos are electrically neutral elementary particles with a mass close to zero. The reason they're known as ghost particles is that, though they are incredibly common, they have no electric charge, meaning they are difficult to detect as they rarely interact with matter.

'Ghost particles' could carry immense amounts of information

Alongside the FASER experiments at the LHC, a series of in-development neutrino observatories, designed to detect neutrino sources in space, have the potential to reveal many of the universe's mysteries. Despite their name, ghost particles might actually provide a wealth of information due to the fact that they don't interact with other matter as they travel through the universe — unlike light particles, photons, which are distorted by interactions as they traverse space. The problem, so far, has been our ability to detect these ghost particles or neutrinos.

Neutrinos are produced in stars, supernovae, and quasars, as well as in human-made sources. It has long been believed, for example, that particle accelerators such as LHC should also produce them, though they have likely gone undetected. Now, a paper published in the journal Physical Review D, provides the first evidence of neutrinos, in the form of six neutrino interactions, at the LHC.

"Prior to this project, no sign of neutrinos has ever been seen at a particle collider," study co-author Jonathan Feng said in a press statement. "This significant breakthrough is a step toward developing a deeper understanding of these elusive particles and the role they play in the universe."

The FASER experiment will be expanded by 2022

Back in 2018, the FASER experiment installed an instrument to detect neutrinos, some 1,575 ft (480 m) down from where particle collisions occur in the LHC. The instrument uses a detector composed of plates of lead and tungsten, which are set apart by layers of emulsion. When neutrinos smash into nuclei in the metals, they produce particles that then travel through the layers of emulsion. This creates marks that are visible following a processing procedure that's somewhat similar to film photography. During the experiments, six of these marks were spotted after processing.

According to Feng, the team is "now preparing a new series of experiments with a full instrument that's much larger and significantly more sensitive," so as to collect more data. This larger version will be called FASERnu. It will weigh 2,400 lb (1,090 kg) — a lot more than the first version's 64 lb (29 kg) — allowing it to detect many more of the elusive ghost particles. David Casper, another co-author of the study, says the UCI team expects FASERnu to "record more than 10,000 neutrino interactions in the next run of the LHC, beginning in 2022."

By UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA - IRVINE NOVEMBER 27, 2021

Scientific first at CERN facility a preview of upcoming 3-year research campaign.

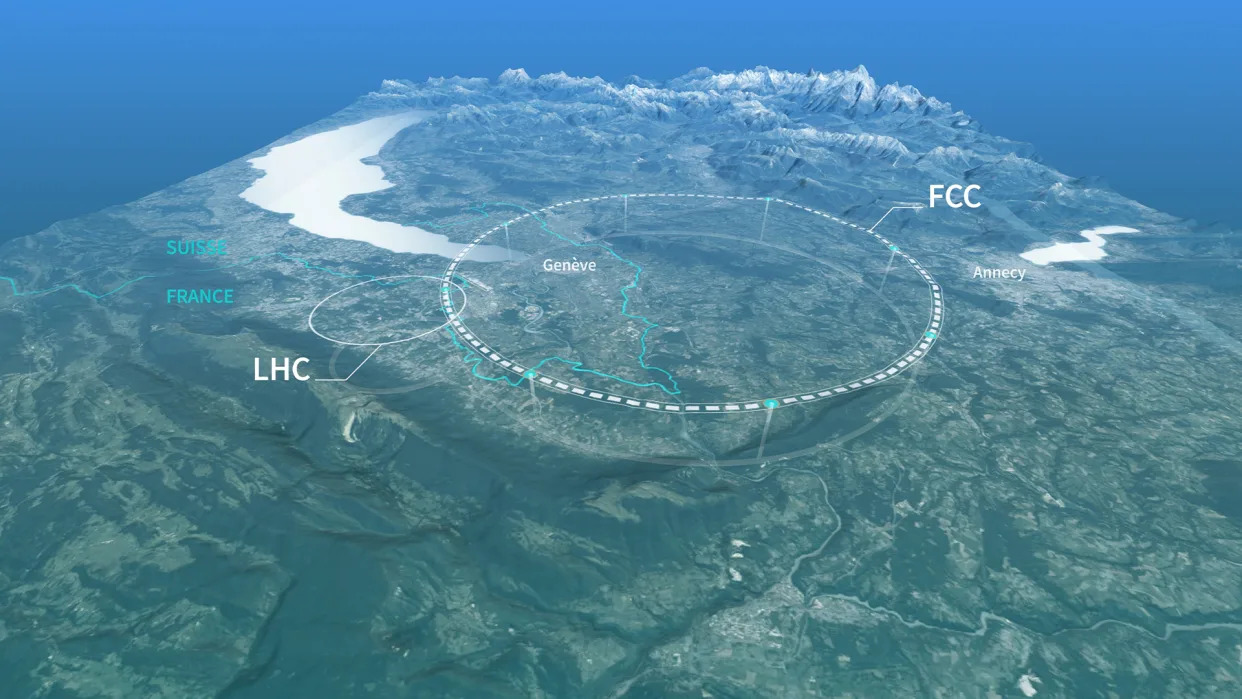

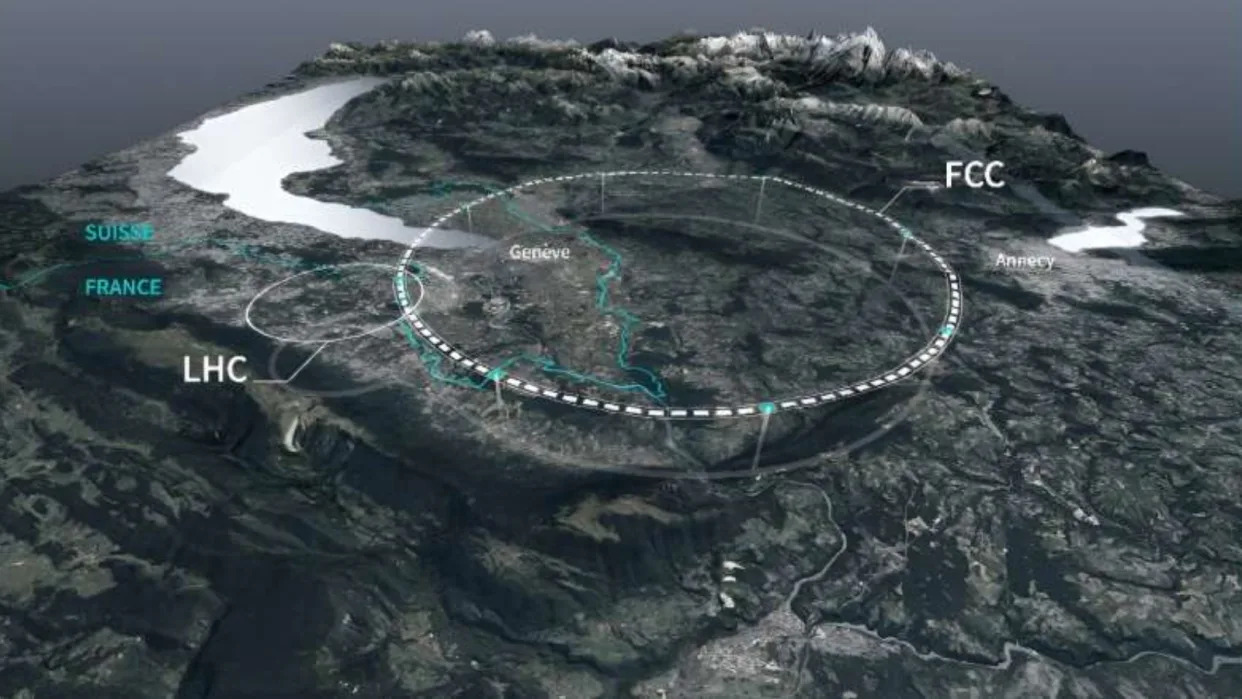

The international Forward Search Experiment team, led by physicists at the University of California, Irvine, has achieved the first-ever detection of neutrino candidates produced by the Large Hadron Collider at the CERN facility near Geneva, Switzerland.

In a paper published on November 24, 2021, in the journal Physical Review D, the researchers describe how they observed six neutrino interactions during a pilot run of a compact emulsion detector installed at the LHC in 2018.

“Prior to this project, no sign of neutrinos has ever been seen at a particle collider,” said co-author Jonathan Feng, UCI Distinguished Professor of physics & astronomy and co-leader of the FASER Collaboration. “This significant breakthrough is a step toward developing a deeper understanding of these elusive particles and the role they play in the universe.”

He said the discovery made during the pilot gave his team two crucial pieces of information.

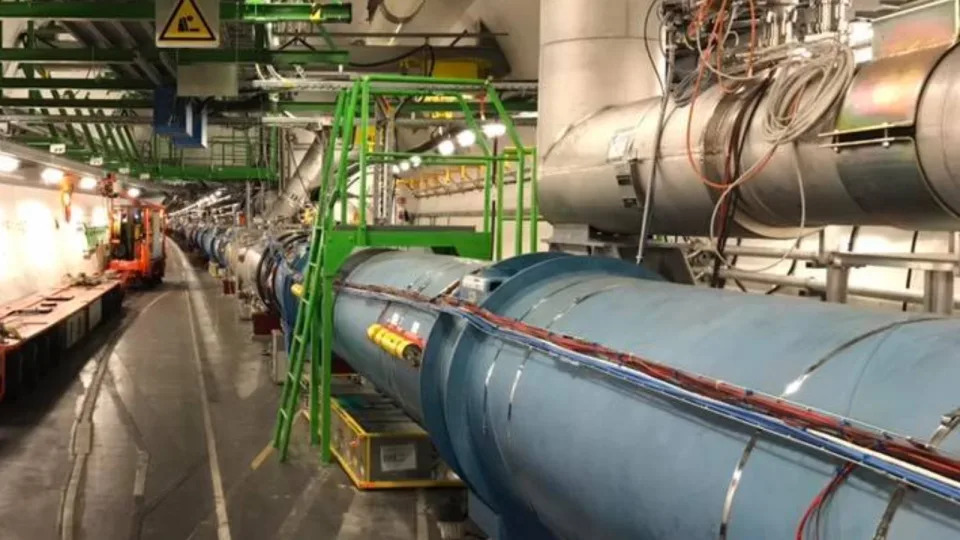

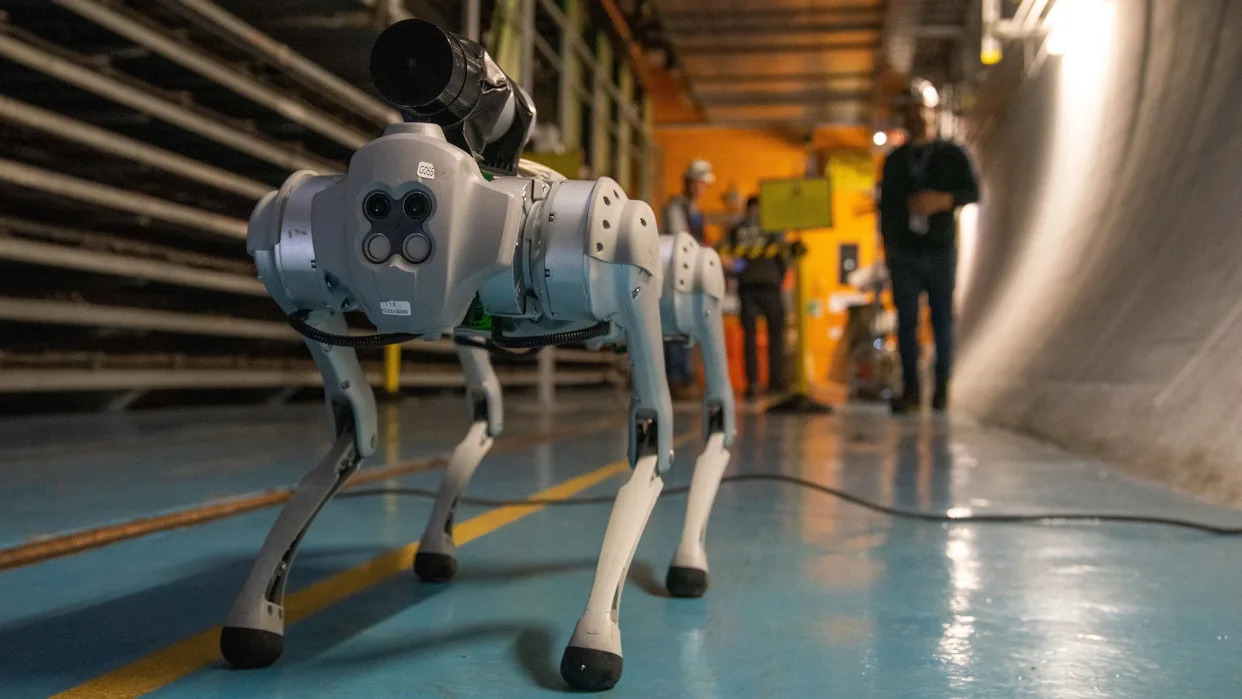

The FASER particle detector that received CERN approval to be installed at the Large Hadron Collider in 2019 has recently been augmented with an instrument to detect neutrinos. The UCI-led FASER team used a smaller detector of the same type in 2018 to make the first observations of the elusive particles generated at a collider. The new instrument will be able to detect thousands of neutrino interactions over the next three years, the researchers say. Credit: Photo courtesy of CERN

“First, it verified that the position forward of the ATLAS interaction point at the LHC is the right location for detecting collider neutrinos,” Feng said. “Second, our efforts demonstrated the effectiveness of using an emulsion detector to observe these kinds of neutrino interactions.”

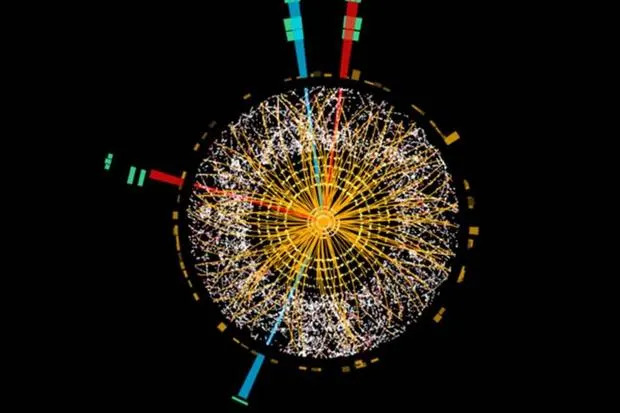

The pilot instrument was made up of lead and tungsten plates alternated with layers of emulsion. During particle collisions at the LHC, some of the neutrinos produced smash into nuclei in the dense metals, creating particles that travel through the emulsion layers and create marks that are visible following processing. These etchings provide clues about the energies of the particles, their flavors – tau, muon or electron – and whether they’re neutrinos or antineutrinos.

According to Feng, the emulsion operates in a fashion similar to photography in the pre-digital camera era. When 35-millimeter film is exposed to light, photons leave tracks that are revealed as patterns when the film is developed. The FASER researchers were likewise able to see neutrino interactions after removing and developing the detector’s emulsion layers.

“Having verified the effectiveness of the emulsion detector approach for observing the interactions of neutrinos produced at a particle collider, the FASER team is now preparing a new series of experiments with a full instrument that’s much larger and significantly more sensitive,” Feng said.

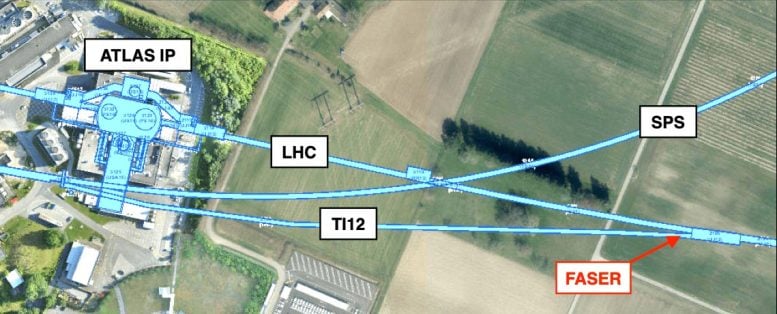

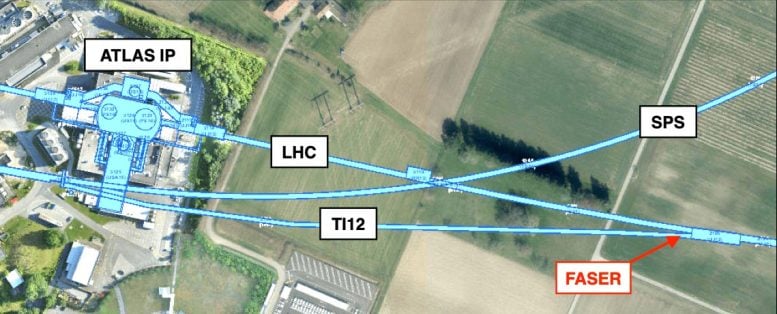

The FASER experiment is situated 480 meters from the ATLAS interaction point at the Large Hadron Collider. According to Jonathan Feng, UCI Distinguished Professor of physics & astronomy and co-leader of the FASER Collaboration, this is a good location for detecting neutrinos that result from particle collisions at the facility. Credit: Photo courtesy of CERN

Since 2019, he and his colleagues have been getting ready to conduct an experiment with FASER instruments to investigate dark matter at the LHC. They’re hoping to detect dark photons, which would give researchers a first glimpse into how dark matter interacts with normal atoms and the other matter in the universe through nongravitational forces.

With the success of their neutrino work over the past few years, the FASER team – consisting of 76 physicists from 21 institutions in nine countries – is combining a new emulsion detector with the FASER apparatus. While the pilot detector weighed about 64 pounds, the FASERnu instrument will be more than 2,400 pounds, and it will be much more reactive and able to differentiate among neutrino varieties.

“Given the power of our new detector and its prime location at CERN, we expect to be able to record more than 10,000 neutrino interactions in the next run of the LHC, beginning in 2022,” said co-author David Casper, FASER project co-leader and associate professor of physics & astronomy at UCI. “We will detect the highest-energy neutrinos that have ever been produced from a human-made source.”

What makes FASERnu unique, he said, is that while other experiments have been able to distinguish between one or two kinds of neutrinos, it will be able to observe all three flavors plus their antineutrino counterparts. Casper said that there have only been about 10 observations of tau neutrinos in all of human history but that he expects his team will be able to double or triple that number over the next three years.

“This is an incredibly nice tie-in to the tradition at the physics department here at UCI,” Feng said, “because it’s continuing on with the legacy of Frederick Reines, a UCI founding faculty member who won the Nobel Prize in physics for being the first to discover neutrinos.”

“We’ve produced a world-class experiment at the world’s premier particle physics laboratory in record time and with very untraditional sources,” Casper said. “We owe an enormous debt of gratitude to the Heising-Simons Foundation and the Simons Foundation, as well as the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and CERN, which supported us generously.”

Reference: “First neutrino interaction candidates at the LHC” by Henso Abreu et al. (FASER Collaboration), 24 November 2021, Physical Review D.

DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevD.104.L091101

Savannah Shively and Jason Arakawa, UCI Ph.D. students in physics & astronomy, also contributed to the paper.