In Hinduism, women creating spaces for their own leadership

By DEEPTI HAJELA

When Sushma Dwivedi started seriously thinking about performing wedding rites and other Hindu religious blessings in New York City and elsewhere, she knew who she needed to talk to - her grandmother.

Together, they went through the mantras that are recited by pandits, the priests who perform Hindu religious rituals, to find the ones that resonated with what Dwivedi was trying to do -- offer Hindu blessings and services that were welcoming of all, irrespective of gender identity, sexual orientation, race, any of it.

Her grandmother isn’t a pandit — in India, as well as in Indian diaspora communities, that’s been a domain that is largely populated by men, with cultural mores at play. But she had a wealth of religious knowledge, of ritual, of proper pronunciation, to share with her granddaughter.

And that her grandmother played an integral role in Dwivedi’s understanding and practice of Hinduism reflects a larger religious reality. Those who study the religion and its traditions say that while there aren’t a lot of women priests (although that is changing in India and in other places), women in Hinduism globally continue to take on leadership roles in other ways - building communities, taking on positions in organizations, passing on knowledge.

“We just jammed together and sort of went through scriptures. ... And in that sense, that’s the ‘old school’-est Hindu way on Earth, right? You pass it down,” Dwivedi said.

After all, it was through her grandparents, immigrants from India, that Dwivedi had been exposed to Hinduism while growing up in Canada. They helped build a Hindu mandir, or temple, in their Montreal community, and made the religion an integral part of her life from childhood.

Full Coverage: Women in religion

___

This story is part of a series by The Associated Press and Religion News Service on women’s roles in male-led religions.

___

Hinduism encompasses a range of practices and philosophies, and has a pantheon of divine figures encompassing both male and female. People can call themselves Hindus and yet practice in different ways from each other. There is no central authority, like an equivalent to the role the pope plays in Catholicism.

So leadership, in India as well as Indian immigrant communities, is decentralized and diverse, encompassing religious scholars, Hindu temple boards and more, said Vasudha Narayanan, a religion professor at the University of Florida who studies Hinduism in India and in the Indian diaspora.

“I would also say that women sometimes create the spaces where they can be leaders in all these other ways,” she said.

Dr. Uma Mysorekar, president of the Hindu Temple Society of North America, sits in her office in the Flushing neighborhood of New York's Queens borough Friday, Dec. 3, 2021. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

They’re women like Dr. Uma Mysorekar, who serves as president of the Hindu Temple Society of North America. It runs one of the oldest Hindu temples in the United States in the Flushing section of New York City’s Queens borough.

Mysorekar, trained as a physician, got involved with the temple in the mid-1980s, and has been part of its administration for years, as it expanded its facilities as well as its programming. There are programs for seniors as well as young adults; the temple kitchen is available on food delivery apps.

Being an administrator wasn’t her intention when she started, Mysorekar said.

“I didn’t get involved to become a president. But when the circumstances were forced in, I did accept that challenge.”

She’s convinced that in Hinduism, women can be leaders simply by virtue of their ability to communicate the faith to others, notably to children.

“How many women have led ... going back to times immemorial, and what they have contributed, it should give you that exemplary feeling,” she said. “It’s not that women have to be priests to be leaders, women have to be able to spread the teachings.”

And in this modern age, when so much vital activity occurs online, women are making a difference there, too, said Dheepa Sundaram, assistant professor of Hindu studies, critical theory and digital religion at the University of Denver.

“If you look at social media spaces, you see a lot of women leading different kinds of groups now,” she said.

She pointed to shubhpuja.com as an example, a site co-founded by a woman, Saumya Vardhan, that allows people all over the world to connect with pandits in India, who perform pujas, the religious rituals, that can be seen via videoconferencing.

“We’re seeing women carve out different spaces in the spirituality ecosystem to find a way to actually gain power in that ecosystem,” she said.

And there are examples of women making inroads even when it comes to being pandits, of pushing back against patriarchal restraints.

Manisha Shete, a practicing Hindu priest, smiles as she performs posthumous rituals for her client's mother at a residence in Pune, India, Wednesday, Oct. 20, 2021. (AP Photo/Abhijit Bhatlekar)

Manisha Shete, 51, a female priest who has been working as the coordinator at Jnana Prabodhini, a Hindu reformist school in Pune in western India that trains men and women to perform rituals, first began to officiate at religious ceremonies in 2008.

Her aspirations stemmed in part from an interest in India’s ancient scriptures; after getting married, she studied

“After my wedding, I studied Indology — the history, culture, languages and literature of India.

“During my research work at the Sanskrit language department in Jnana Prabodhini ... I felt that I can do this and I should do it. It was my favorite subject,” Shete told The Associated Press.

Shete said at her school in Pune, where the course for the priesthood can extend up to 18 months, 80% of the students were women, including many who had been housewives and many others who voluntarily their jobs to enter the school.

She said the demand for female priests is growing in urban areas, especially among young women, and she often gets requests even from Indian families overseas to conduct rituals.

“People have started accepting women priests. Every reform comes with some obstacles. But it is happening.”

___

Associated Press religion coverage receives support from the Lilly Endowment through The Conversation U.S. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

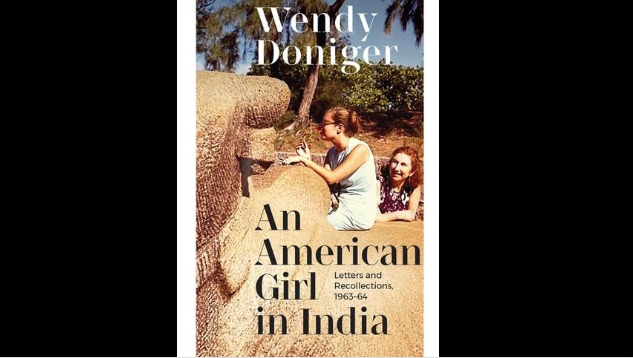

S1 E4 Wendy Doniger on Hinduism – Thinking About Religion

Dr. Wendy Doniger’s On Hinduism is a sort of captstone on an epic career exploring Hindu literature, religion, and history. In this conversation we discuss a number of themes from the book, including her own religious background, common misconceptions about Hinduism, the caste system, orientalism, the so-called “Hindu Trinity,” Hindu nationalism, a controversy in India over the charge that she committed …

Wendy Doniger and the Hindus | by Murali Balaji | The New ...

In her essay “India: Censorship by the Batra Brigade” [NYR, May 8], Wendy Doniger touches on a number of issues when it comes to the academic study of religion and larger questions of representation. She frames the debate over her book, as well as other topics when it comes to Hinduism, as one between Hindu right-wing activists and scholars, which essentializes a complex history that involves academic …

On Hinduism - Wendy Doniger - Oxford University Press

Wendy Doniger. Includes more than 60 essays and lectures spanning the decades-long career of one of Hinduism's most prominent scholars. Examines a rich array of Hindu concepts--polytheism, death, gender, art, contemporary puritanism, non-violence, and many more. On Hinduism. Wendy Doniger.