Mickleburgh’s take on BC unions

April 29th, 2019

The notion that workers should collectivize to support one another and prevent exploitation is increasingly viewed as arcane in the Age of Tweets. The Winnipeg General Strike happened 100 years—and few Canadians can tell you what it was, and what happened.

Society barely bats an eye as unionization of the workplace declines, and more and more workers are hired under contract with no job security and few benefits. Rights and conditions workers fought for years to achieve – some gave their lives – are being steadily being eroded.

Hence judges selected Rod Mickleburgh’s On the Line: A History of the British Columbia Labour Movement (Harbour $44.95) as the 2019 winner of the George Ryga Award for Social Awareness.

The two runners-up were Chelene Knight for her second book, Dear Current Occupant (Book Thug) and Sarah Cox for Breaching the Peace: The Site C Dam and a Valley’s Stand Against Big Hydro (On Point Press).

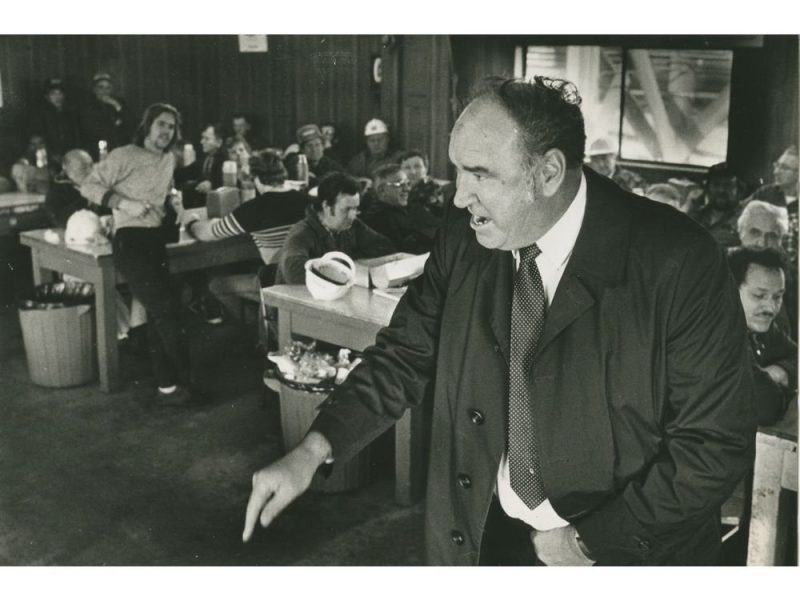

Mickleburgh, formerly a labour reporter for both the Vancouver Sun and Province and a senior writer for The Globe and Mail, has documented the broad historical sweep of what has been Canada’s most volatile and progressive provincial labour force, re-educating British Columbians to why unions are essential for a progressive society.

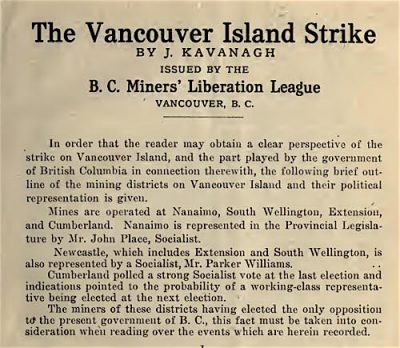

The story begins back in 1849 when Scottish labourers went on strike to protest barbaric working conditions at B.C.’s first coal mine at Fort Rupert on Vancouver Island and continues into the second decade of the 21st century to recount the successful campaign led by the B.C. Teacher’s Federation (BCTF) to improve classroom conditions and class sizes.

The Ryga Award was presented to Rod Mickleburgh in Victoria—on Saturday, April 27th—at the James Bay Library branch, 385 Menzies Street. The City of Vancouver also declared Author Appreciation Day in his honour.

Here is Rod Mickleburgh’s acceptance speech.

*

It’s hard to put into words how honoured and pleased I am to receive this year’s George Ryga Award for Social Awareness. But I guess words are my business, so here goes.

It’s hard to put into words how honoured and pleased I am to receive this year’s George Ryga Award for Social Awareness. But I guess words are my business, so here goes.

I’m honoured, first of all, because this award carries the name of George Ryga. In addition to being such a celebrated BC writer, he takes me back to my long-lost youth. I am old enough to have seen the storied Vancouver Playhouse production of The Ecstasy of Rita Joe, George Ryga’s powerful play about the plight of an indigenous woman in the big city. There had never been anything like it in the then tame landscape of Canadian theatre and it broke the hearts of all who saw it.

A year later, in 1969, when I began my so-called brilliant career as sports editor of the mighty Penticton Herald, I discovered the famous man lived just up the road in Summerland. A guy on the paper kept regaling me about the rambunctious, wine-enhanced gatherings he went to at George Ryga’s place, a place that welcomed anyone who aspired to write. I remember being so jealous. As a lowly sports guy writing about the local junior hockey team, I felt too intimidated to think I would fit in.

Now, irony of irony, here I am accepting the George Ryga Award. It’s a funny old world.

I can’t resist adding one more example of George Ryga and me. I noticed on Wikipedia yesterday, that as a young man, he attended the World Assembly for Peace in Helsinki in 1955. My father was at the very same conference.

More importantly, I am also deeply honoured and pleased that this is the George Ryga Award for Social Awareness, something that was fundamental to Ryga’s own writing. Given the way unions and their contributions to society are so often marginalized, social awareness is not something one might normally associate with a history of the BC labour movement, however well done it is. (smile).

But when you look at all those things we take for granted today – the eight-hour day, the five-day work week, paid vacations, overtime, sick leave, pensions, safe working conditions, maternity leave, pay equity and on and on – where did that come from? How did that happen? Not one was granted voluntarily by benevolent, Nice Guy employers. Each and every breakthrough had to be fought for by workers and their unions. And it was never easy, especially in the days when unions had no rights and bosses could pretty well do as they pleased, backed all the way by governments and police.

As someone who spent 15 years as a labour reporter, in the days when there WERE labour reporters, I thought I knew something about the sacrifices of those early union members and the heroic struggles of the past. I had no idea. What I didn’t know, until I began researching for this book, and this came as a total surprise, was that until World War Two when legislation finally compelled employers to bargain with their unions, just about every single major strike was lost. Time after time, from the 1870s onward, workers would take on unscrupulous employers, wanting only a decent wage and working hours, a safe workplace and recognition of their union, but the deck was always stacked against them.

David Lester has depicted the “Battle of Ballantyne Pier” when locked-out waterfront workers fought police in Vancouver in 1935.

The moment a union went on strike, the company would hire strike-breakers, protected by private security goons, police and sometimes even the militia. If the strikers tried to stop the scabs, guess who went to jail? As well, workers who went on strike were regularly blacklisted, meaning they could never return to their old jobs. With strike-breakers maintaining normal production and companies, under no requirement to bargain, supported by governments, police, the media and hysterical law-and-order citizens, there was virtually no way for a union to win. Yet, in spite of defeat after defeat, workers kept fighting back.

While most of us probably have this general awareness that unions had a tough time in the old days, it’s only when you examine events in individual dispute after individual dispute that you realize just how terrible the injustices were and what workers and their unions went through. What they sacrificed for rights and benefits that we enjoy today is truly remarkable. Some paid with their lives. Ginger Goodwin you probably know, but lest we forget, Frank Rogers, shot dead on the Vancouver waterfront in 1903 by a CPR security guy and, incidentally one of the subjects of Geoff Meggs’ recent book, Strange New Country, Joseph Mairs, a young coal miner and cyclist arrested for virtually nothing during the valiant TWO YEAR STRIKE by Vancouver Island coal miners who died in Oakalla, Bob Gardner, savagely beaten by a rogue cop during the fierce union Battle of Blubber Bay on Texada Island in 1938. He never recovered from the four broken ribs he suffered and died, like Joseph Mairs, in Oakalla.

Hundreds, if not thousands of other workers, were clubbed, beaten, jailed, fined, blacklisted, red-baited, and deported – all for the great crime of fighting for decent wages and working conditions and the right to form a union. It’s really a shocking history.

Hundreds, if not thousands of other workers, were clubbed, beaten, jailed, fined, blacklisted, red-baited, and deported – all for the great crime of fighting for decent wages and working conditions and the right to form a union. It’s really a shocking history.

But over time, by fighting back, those basic gains were won that benefited all British Columbians, not just those in a union. We owe them so much.

So I applaud and thank the judges for recognizing On the Line, a history of the BC labour movement, for bringing to light unions’ contributions to society and enhancing our social awareness. And, dare we hope, perhaps ever inspire people to renew the fight for better lives in this debilitating gig economy.

It’s mystifying why these courageous early trade unionists are not more known today. Some are true heroes. We now celebrate the suffragettes and other women activists, activists of colour, First Nations leaders, Louis Riel, and so on, as we should. But try and find a union leader on a stamp, on our money, on a street sign or even in the histories we teach in the schools. With the notable exception of Ginger Goodwin, it’s as if they never existed.

We now have Ginger Goodwin Way again, up near Cumberland, and hopefully this time it will be left in place, and not taken down by the next non-NDP government.

Otherwise, we have streets and landmarks named after politicians, ruthless anti-union capitalists (hello there, Robert Dunsmuir) and the likes of the notorious Joseph Trutch, who was responsible for reducing the size of BC First Nations reserves by more than 90 per cent in the 19th century. Why not union leaders. It’s time.

At this point, I should point out that On the Line covers 150 years of labour history, not just the bad old, head-bashing days. It’s a top to bottom chronicle that carries on right up the landmark Supreme Court of Canada in late 2016 that delivered victory to BC teachers after 14 years of fighting the stripping of their contracts by the Campbell government in 2002.

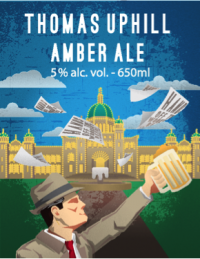

Oh, and it also manages to work in the recent unveiling of the Tom Uphill Amber Ale by a Victoria brewery, in honour of one of those great labour characters we should all know more about. In fact, maybe after this is over, we can all go and quaff a few.

Despite my extolling unions and those many heroes of the past. I don’t want to give the impression that On the Line is some sort of one-note pro-union propaganda screed. Unions and their leaders, like everything else, are not perfect and never have been. This is reflected in the book. The Red-baiting, the bitter internal divisions and the racism directed against Asian immigrants that characterized the labour movement for years, an attitude shared by most of the white population in BC, are all addressed. This is a warts-and-all history.

But what a history. It’s a rollicking tale, full of colourful, larger-than-life characters and compelling stories. I did my best to make On the Line a narrative, not an academic tract, And I think I succeeded. It’s a good read, he said modestly. And the workers deserved no less.

At the same time, On the Line focuses deliberately on more than just unions and strikes and the accomplishments of dead white guys, however heroic. Diversity is a strong part of the book, bringing to light the struggles of exploited immigrant workers, the role of women and particularly, the contribution of BC’s indigenous people to the province’s economy in the 19th century.

Not many know that BC’s first workers, and a majority of the population until 1890, were from the First Nations. They discovered coal on Vancouver Island and were the first miners. They were also loggers, early sawmills workers, longshoremen, labourers, farm hands, horse packers, sealers and of course, they were particularly dominant in the fishing industry, on the water and in the canneries. Without them, few economic wheels would have turned in 19th century British Columbia. They even formed a union or two. But, like trade unions, they, too, have been excluded from BC histories.

I am also proud of another feature of the book not normally part of labour histories. I pay a lot of attention to workplace health and safety and the role of the workers’ compensation board, subjects that rarely make headlines. But I believer they are more important to individual workers than any number of strikes or good contracts. What could be more basic than going to work and coming back safe and sound?

I can’t thank the BC Labour Heritage Centre enough for choosing me to tell labour’s rich history. Jack Munro, the Heritage Centre’s founder, had a vision that the contribution of workers and their unions was shamefully unknown, and needed to be told. As someone who spent years covering labour, I couldn’t agree more. Really, the Labour Heritage Centre had me at hello.

I would also like to thank Howard White of Harbour Publishing who never lost faith in my ability to do the job, my forebearing editor Silas White, the tireless Ken Novakowski and Donna Sacuta of the Labour Heritage Centre, and the community savings credit union, without whose deep generous pockets, I would still be writing labour history on Twitter.

And a heartfelt thank you, with love, to my life partner, Lucie McNeill, who was so supportive of this disorganized, grumbling old codger throughout the close to three years this project consumed me, the basement and most of the dining room.

On behalf of those labour leaders, union members and ordinary workers who fought so long and sacrificed so much to make British Columbia a better place, I accept the George Ryga Award for Social Awareness.

A last postscript. For a number of reasons, unions today are not what they are. But they are far from a spent force, and they could be vital once again in combatting a new economy in which increasing numbers of workers are becoming virtual slaves to the gig economy – longer hours, short-term contracts, no job security, few benefits, part-time work as the new normal. It’s the next great challenge for unions. It won’t be easy, but then, when has it ever been easy for unions.

Solidarity, and thanks for coming out!

*

During his long career, Rod Mickleburgh has worked for the Penticton Herald, Prince George Citizen, Vernon News and CBC TV, in addition to the Sun, Provinceand Globe and Mail. In 1992, he was nominated for a National Newspaper Award; in 1993, he was a co-winner, with André Picard, of the Michener Award.

Mickleburgh’s first book was Rare Courage: Veterans of the Second World War Remember (M&S 2005), a collection of 20 memoirs profiling Canadian veterans of World War II (with Rudyard Griffiths, executive director of the Dominion Institute) and he earned the 2013 Hubert Evans Non-Fiction Prize for The Art of the Impossible (Harbour 2012), co-authored with Geoff Meggs. It remains the definitive book on the early 1970s era of the NDP in British Columbia, in tandem with Dave Barrett’s autobiography, Barrett, A Passionate Political Life (Douglas & McIntyre, 1995), that was co-written with William Miller.

Judges for the Ryga Award were professor and author Trevor Carolan, Joe Fortes VPL branch manager Jane Curry and freelance writer and author Beverly Cramp.

*

“The eight-hour day, the five-day work week, paid vacations, overtime, sick leave, pensions, safe working conditions, maternity leave, pay equity and on and on – where did that come from? How did that happen? Not one was granted voluntarily by benevolent, Nice Guy employers” — Rod Mickleburgh

Please follow and like us:

No comments:

Post a Comment