The passionate logic of Evald Ilyenkov

April 17th, 2019

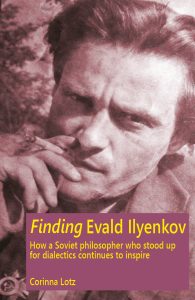

Finding Evald Ilyenkov is a bit of a detective story, charting the rediscovery of long-buried events and writings by a remarkable Soviet-era philosopher.

Much of his work is only now becoming available in English and other languages, as the imperative to study his thought becomes more urgent and widespread.

Evald Ilyenkov never wanted to write for the drawer, but too often his work was either not published or published in a censored form. It is astonishing that even with these problems, when people outside the USSR encountered his writings, they were excited and impressed.

As a young philosophy student, he battled to rescue Marxism from the dead hand of official formulae and the triviality of Soviet neo-positivism. This book explains how he was discovered in Britain, America and the Nordic countries, and how his influence continues to grow.

Ilyenkov (born 1924 and died by his own hand in 1979) is increasingly seen as a crucial 20th century thinker. He made an entirely original contribution to philosophy in the USSR – “the hardest country in which to be a Marxist”, as a Russian theorist has noted.

His achievement shows that whilst the victory of Stalinism in the Soviet Union appeared complete and hegemonic, there was an underground of Marxists who continued to work on concepts for a socialist future.

He and his co-thinkers fought for the acceptance of philosophy as a special study, not in a purist way but as Marx did – as a theoretical guide to practices to bring about a communist society.

He denied claims that the Soviet Union had fully achieved socialism and was on its way to being a communist state – a fantastically brave thing to do. He did it not as a politician or a dissident but as a communist and a philosopher.

He was one of the Sixties generation, who believed that the Khrushchev Thaw would make it possible to regenerate Soviet Marxism. In that spirit he joined battle with the dogmatic materialists of the Soviet academy and the crude positivists who dominated science and social science.

This approach is seen in his courageous letter to the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party, written in the late 1960s as the shutters were again coming down. He boldly stated that Marx’s and Lenin’s actual thought had practically zero influence in Soviet philosophy; that neo-positivism was rampant grafting ideas taken from cybernetics into philosophy, and that Soviet economists knew a great deal more about the economies of the US and Europe than they did about their own economy.

Philosophy can seem remote from practical problems in the sciences, pedagogy or politics. And yet, this book – written simply for Marxists and non-Marxist to understand – shows that the concepts which Ilyenkov championed can help us to understand the complex world of today from the standpoint of changing it.

He offers powerful assistance to activists who are battling the hegemony of neo-liberal capitalism whether in politics, education or the social sphere.

For those who prefer to stick to the “pre-Capital” Marx of the Economic Manuscripts – the so-called “humanist” Marx – Ilyenkov offers little comfort. He is focused on the Marx of Capital and sees his task as developing Marx’s method in philosophy – the book Marx could not find time to write.

The Ideal, Dialectical Logic, the Ascent from the Abstract to the Concrete – these key concepts were researched by Ilyenkov as active principles, with real force in the movement of nature, society and thought. He was concerned with the development of theory as a collective human endeavour; he completely disallowed the reduction of thinking to matter whilst also denying it as an activity solely taking place inside the head of the human individual.

The importance of human thought and ideas exchanged and developed with others in a co-operative and creative way – this was what Ilyenkov provided in his classes, in his home and in his work on the education of deaf/blind children.

In the age of burgeoning artificial intelligence and logarithmic data mining by social media giants, Ilyenkov’s championing of the importance and uniqueness of human thought is poignant and relevant.

In his essay on the Ideal and in his study of the concept of ‘substance’ in Spinoza he offers a brilliant way of understanding the dialectical relationship between social being, social consciousness, thought and the individual. In the era of “fake news” and the rising right, it offers a key to understanding how populism can take hold, as an aspect of degeneration of culture and society arising from the crisis of neoliberal capitalism.

A new ideal of human society is, willy nilly, being created out of this crisis. Ilyenkov with his focus on theoretically guided practice and collective action suggests how we can counter social and political degeneration. It is the actions and practical achievements of actual human beings, working in politics, economy, social and cultural initiatives – that can co-create an alternative ideal to that which is required for the continued existence of capitalism.

In the book, contributions by practitioners from a wide range of fields explain how they first encountered Ilyenkov, and what his work means to them in their different fields. You get a sense that Ilyenkov would have thoroughly enjoyed participating in their work which makes it all the more sad that he was prevented from participating in international researches in his lifetime.

The International Friends of Ilyenkov, jointly co-ordinated by the author of this book, offers exactly the kind of collective and supportive atmosphere Ilyenkov fostered in his life. The difference is that we are able to include people from across borders and continents.

From neoliberal hegemony to the development of AI to the purpose of education, IFI hosts online seminars with presentations from researchers and activists and positive, open discussion. There are occasional face-to-face conferences – so far in Helsinki and Copenhagen and. . . watch this space. When you’ve read this book, hopefully you will feel inspired to join this expanding global conversation.

Finding Evald Ilyenkov by Corinna Lotz (£5) can be ordered here.

Marx & Philosophy Review of BooksReviews

‘Finding Ilyenkov: How a Soviet Philosopher Who Stood Up for Dialectics Continues to Inspire’ by Corinna Lotz

reviewed by Dom Taylor

Corinna Lotz

Finding Ilyenkov: How a Soviet Philosopher Who Stood Up for Dialectics Continues to Inspire

Lupus Books, London, 2019, 64 pp., £ 8.50, pb

ISBN 9781916031814

Reviewed by Dom Taylor

About the reviewer

Dom Taylor is a librarian at the University of Manitoba.

Corinna Lotz

Finding Ilyenkov: How a Soviet Philosopher Who Stood Up for Dialectics Continues to Inspire

Lupus Books, London, 2019, 64 pp., £ 8.50, pb

ISBN 9781916031814

Reviewed by Dom Taylor

About the reviewer

Dom Taylor is a librarian at the University of Manitoba.

He holds an MA in Philosophy and an MLIS.

Corinna Lotz’ Finding Ilyenkov can be read in a few hours, but for those readers taken with its ideas and appeal to the relevance of Ilyenkov’s life and theory, this book provides a salient and fecund starting point for any variety of in-depth engagements relating to Ilyenkov, dialectical materialism and creative Soviet Marxism. This is a lovingly and comprehensively researched introduction to Ilyenkov’s thought, history and influence that will pique the interest of non-scholars and scholars alike. The book is divided into six concise chapters, including the introduction, which follow the course of Ilyenkov’s life, his work and its dissemination in a broadly chronological manner.

In the introduction and first chapter, the author frames her concise, fluid and well-analysed exposition of Ilyenkov’s body of work in relation, or more often in opposition, to past and current philosophical schools, including the official Soviet doctrine of dialectical materialism, diamat. Using the recently discovered and translated full text of the ‘Theses on Philosophy’ (1954), presented by Ilyenkov and his colleague only one year after Ilyenkov had completed his dissertation, Lotz shows that Ilyenkov was not merely content with rehearsing Soviet orthodoxy, but wanted philosophy to be a living practice (2-6). The ‘Theses’ are an open attack on the Soviet philosophy of the time, insisting that philosophy still had a role as an independent area of inquiry with both epistemological and metaphysical import. Among other things, the ‘Theses’ made positive references to Hegel, which provided the philosophical establishment of the time with material for charges of idealism and revisionism (7). This presentation set both Ilyenkov and his co-author apart from the majority of their colleagues, but also provided the basis on which Ilyenkov would be singled-out for scathing personal and professional critiques and censure the rest of his life (6-8).

Even though Ilyenkov was given a short reprieve during the Khrushchev Thaw (1956-1964), his work nonetheless came under constant and fierce attack primarily because it openly cut against the grain of official diamat, which had been formalized in Stalin’s Dialectical and Historical Materialism (1938). In her exposition of Ilyenkov’s ideas, paying specific attention to the concept of the ‘Ideal,’ Lotz puts welcome emphasis on Ilyenkov’s embrace of contradiction in the face of the Kantian antinomies of reason (12-13), which mirrors Hegel’s positive reconfiguration and affirmation of Kant’s antinomies as something ‘reason must run up against’ and through (Hegel, 2010: 158). In the most general terms, Ilyenkov’s ‘Ideal’ is a concept that refers to the cultural and material products of humanity achieved through activity and labour that is dependent upon, but cannot be reduced to individual consciousness and action (13-14). The Ideal provided Ilyenkov with a method, true to both Marx and his Hegelianism, to critique the neo-Kantian and positivist trends prevalent in the philosophical culture of his day. Furthermore, Ilyenkov saw his conception of the Ideal affirming the dialectical contradiction found in Marx’s Capital (e.g. use value vs. exchange value) (12). To this end, Lotz argues that according to Ilyenkov,

[t]he Ideal is internally contradictory. It exists in a negated way in the individual but also has an independent existence outside of the individual. It is objective because it is not the property of, nor does it arise from, one individual’s actions in the world— it is the objective form of the whole social existence of human beings (13).

For Ilyenkov, the positive (re)affirmation of contradiction provided the necessary grounding for any philosophy that wished to move beyond the neo-Kantian confines and strictures of bourgeois thought (13-14).

Chapters two to four provide an overview of the dissemination of Ilyenkov’s work at home and abroad during and after his lifetime. Lotz gives a fascinating description of how Trotskyists, primarily Gerry Healy, played a key role in bringing Ilyenkov’s ideas to the United Kingdom in the late 1970s, where they both informed theoretical debates and questions of political practice (19-21). She also discusses the eventual controversy raised by some Trotskyists about promoting a ‘Stalinist,’ which Lotz indicates was a reductive misnomer at best (22-23). From here, Lotz details how Soviet ‘openness’ in the early 1980s helped introduce and solidify Ilyenkov’s contribution to education and psychology in the United States and a number of Scandinavian countries (27). In these contexts, Ilyenkov’s focus on activity as being the generator of the Ideal and, therefore, knowledge, among other things, was used for a number of purposes, including providing a theoretical basis for the primacy of practice in the process of learning and child development (30-33, 41).

Chapter 4 hones in on Vesa Oittenen’s engagement with and promotion of Ilyenkov’s ideas. Given that Oittenen is an important Finish scholar that has written extensively on Ilyenkov’s philosophy, including critical appraisals of Ilyenkov’s work, this chapter will be of special interest to those engaging with current scholarship on Ilyenkov from a philosophical perspective. Namely, Lotz describes Oittenen’s leadership in convening an international symposium on Ilyenkov in 1999, which resulted in the publication of Evald Ilyenkov’s Philosophy Revisited in 2000, the second English-language full-length study of Ilyenkov (41). Lotz also identifies the significance of the David Bakhurst’s 1991 Consciousness and Revolution in Soviet Philosophy: From the Bolsheviks to Evald Ilyenkov on increasing Ilyenkov’s presence in Enlgish-language philosophy.

The final chapter brings us to current day. In this chapter, Lotz identifies current projects in Ilyenkov studies, including the work of Andy Blunden in translating and editing Ilyenkov’s works for the Internet Marxist Archive, as well as Ilyenkov scholar Andrey Maidanksy in maintaining a ‘multi-lingual Ilyenkov Intenet archive’ (46). This chapter also includes a fascinating account of the author’s own engagement with Ilyenkov, through the UK Marxists group, during the early 1990s (43-44). This involved members of UK Marxists, including Lotz, going to Russian in order to meet with and interview Ilyenkov’s former classmates, colleagues and friends. Among other things, these interviews helped reveal some of the context surrounding Ilyenkov’s tragic suicide in 1979 (44, 48).

Reading this book was highly engaging and inspiring in terms of how it makes explicit Ilyenkov’s continued relevance to philosophy, education, and psychology, despite the efforts made during his lifetime to censor, if not bury, his work. The only note of caution that can be raised is that Lotz’ approach to Ilyenkov lacks any significant critical commentary. While there is sufficient attention paid to Ilyenkov’s critics in the diamat state apparatus, this is done largely to emphasize that Ilyenkov was single-minded in his pursuit of good philosophy and willing to challenge calcified and hostile structures of power. Lotz’ treatment of Oittenen could have benefitted from an engagement with Oittenen’s criticisms of Ilyenkov, which are hinted at (39). Further, the book seems to describe Ilyenkov as primarily being focused on epistemology (11-12, 29, 31), whereas, as Oittenen is cited in the book as saying, Ilyenkov ‘stubbornly insisted on the unity— yes, the identity— of dialectics, logics, and the theory of cognition’ (p37). As this hints at, Ilyenkov, in fact, rejected the epistemological focus of his neo-Kantian colleagues, which puts knowledge within the confines of the conditions for the possibility of knowing. The neo-Kantianism that Ilyenkov rails at extensively in his work (cf. Ilyenkov, 2018), puts logic in the mind alone, leaving thought out of touch with the world. By extending logic to dialectics and the theory of cognition, Ilyenkov is in effect unifying epistemology and metaphysics, making logic immanent in the world as a concrete totality. Having said this, it should be noted that the Lotz acknowledges being restricted by space and, therefore, what she could tackle in a slim volume. This should not detract from anyone interested in Marxism, including scholars interested specifically in creative Soviet Marxism and Ilyenkov, from engaging with this illuminating work. This call for a return to Ilyenkov is welcome.

29 August 2019

References

Hegel, G.W.F. 2010 The Science of Logic Trans. G. Di Giovanni, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Ilyenkov, Evald 2018 Lenin’s Idea of the Coincidence of Logic, Theory of Cognition and Dialectics Intelligent Materialism: Essays on Hegel and Dialectics Historical Materialism Book Series, Volume 181, Ed. and Trans. E.V. Pavlov, Leiden: Brill

URL: https://marxandphilosophy.org.uk/reviews/17316_finding-ilyenkov-how-a-soviet-philosopher-who-stood-up-for-dialectics-continues-to-inspire-by-corinna-lotz-reviewed-by-dom-taylor/

This review is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0

PDF OF BOOK

Soviet Psychology: ACTIVITY AND IDEALISM ... - Marxists Internet Archive

https://www.marxists.org › books › ilyenkov › ideal-activity

Evald Vasilyevich Ilyenkov (1924-1979). 1. Philosophy, 2. ... lationship of the material and the ideal in human life. ... process of goal directed human actions.

e-flux Journal #88 - Alexei Penzin - Contingency and Necessity in Evald Ilyenkov’s Communist Cosmology

https://www.e-flux.com/journal/88/174178/contingency-and-necessity-in-evald-ilyenkov-s-communist-cosmology/

The Ilyenkov Triangle: Marxism in Search of its Philosophical Roots

Andrey Maidansky

Corinna Lotz’ Finding Ilyenkov can be read in a few hours, but for those readers taken with its ideas and appeal to the relevance of Ilyenkov’s life and theory, this book provides a salient and fecund starting point for any variety of in-depth engagements relating to Ilyenkov, dialectical materialism and creative Soviet Marxism. This is a lovingly and comprehensively researched introduction to Ilyenkov’s thought, history and influence that will pique the interest of non-scholars and scholars alike. The book is divided into six concise chapters, including the introduction, which follow the course of Ilyenkov’s life, his work and its dissemination in a broadly chronological manner.

In the introduction and first chapter, the author frames her concise, fluid and well-analysed exposition of Ilyenkov’s body of work in relation, or more often in opposition, to past and current philosophical schools, including the official Soviet doctrine of dialectical materialism, diamat. Using the recently discovered and translated full text of the ‘Theses on Philosophy’ (1954), presented by Ilyenkov and his colleague only one year after Ilyenkov had completed his dissertation, Lotz shows that Ilyenkov was not merely content with rehearsing Soviet orthodoxy, but wanted philosophy to be a living practice (2-6). The ‘Theses’ are an open attack on the Soviet philosophy of the time, insisting that philosophy still had a role as an independent area of inquiry with both epistemological and metaphysical import. Among other things, the ‘Theses’ made positive references to Hegel, which provided the philosophical establishment of the time with material for charges of idealism and revisionism (7). This presentation set both Ilyenkov and his co-author apart from the majority of their colleagues, but also provided the basis on which Ilyenkov would be singled-out for scathing personal and professional critiques and censure the rest of his life (6-8).

Even though Ilyenkov was given a short reprieve during the Khrushchev Thaw (1956-1964), his work nonetheless came under constant and fierce attack primarily because it openly cut against the grain of official diamat, which had been formalized in Stalin’s Dialectical and Historical Materialism (1938). In her exposition of Ilyenkov’s ideas, paying specific attention to the concept of the ‘Ideal,’ Lotz puts welcome emphasis on Ilyenkov’s embrace of contradiction in the face of the Kantian antinomies of reason (12-13), which mirrors Hegel’s positive reconfiguration and affirmation of Kant’s antinomies as something ‘reason must run up against’ and through (Hegel, 2010: 158). In the most general terms, Ilyenkov’s ‘Ideal’ is a concept that refers to the cultural and material products of humanity achieved through activity and labour that is dependent upon, but cannot be reduced to individual consciousness and action (13-14). The Ideal provided Ilyenkov with a method, true to both Marx and his Hegelianism, to critique the neo-Kantian and positivist trends prevalent in the philosophical culture of his day. Furthermore, Ilyenkov saw his conception of the Ideal affirming the dialectical contradiction found in Marx’s Capital (e.g. use value vs. exchange value) (12). To this end, Lotz argues that according to Ilyenkov,

[t]he Ideal is internally contradictory. It exists in a negated way in the individual but also has an independent existence outside of the individual. It is objective because it is not the property of, nor does it arise from, one individual’s actions in the world— it is the objective form of the whole social existence of human beings (13).

For Ilyenkov, the positive (re)affirmation of contradiction provided the necessary grounding for any philosophy that wished to move beyond the neo-Kantian confines and strictures of bourgeois thought (13-14).

Chapters two to four provide an overview of the dissemination of Ilyenkov’s work at home and abroad during and after his lifetime. Lotz gives a fascinating description of how Trotskyists, primarily Gerry Healy, played a key role in bringing Ilyenkov’s ideas to the United Kingdom in the late 1970s, where they both informed theoretical debates and questions of political practice (19-21). She also discusses the eventual controversy raised by some Trotskyists about promoting a ‘Stalinist,’ which Lotz indicates was a reductive misnomer at best (22-23). From here, Lotz details how Soviet ‘openness’ in the early 1980s helped introduce and solidify Ilyenkov’s contribution to education and psychology in the United States and a number of Scandinavian countries (27). In these contexts, Ilyenkov’s focus on activity as being the generator of the Ideal and, therefore, knowledge, among other things, was used for a number of purposes, including providing a theoretical basis for the primacy of practice in the process of learning and child development (30-33, 41).

Chapter 4 hones in on Vesa Oittenen’s engagement with and promotion of Ilyenkov’s ideas. Given that Oittenen is an important Finish scholar that has written extensively on Ilyenkov’s philosophy, including critical appraisals of Ilyenkov’s work, this chapter will be of special interest to those engaging with current scholarship on Ilyenkov from a philosophical perspective. Namely, Lotz describes Oittenen’s leadership in convening an international symposium on Ilyenkov in 1999, which resulted in the publication of Evald Ilyenkov’s Philosophy Revisited in 2000, the second English-language full-length study of Ilyenkov (41). Lotz also identifies the significance of the David Bakhurst’s 1991 Consciousness and Revolution in Soviet Philosophy: From the Bolsheviks to Evald Ilyenkov on increasing Ilyenkov’s presence in Enlgish-language philosophy.

The final chapter brings us to current day. In this chapter, Lotz identifies current projects in Ilyenkov studies, including the work of Andy Blunden in translating and editing Ilyenkov’s works for the Internet Marxist Archive, as well as Ilyenkov scholar Andrey Maidanksy in maintaining a ‘multi-lingual Ilyenkov Intenet archive’ (46). This chapter also includes a fascinating account of the author’s own engagement with Ilyenkov, through the UK Marxists group, during the early 1990s (43-44). This involved members of UK Marxists, including Lotz, going to Russian in order to meet with and interview Ilyenkov’s former classmates, colleagues and friends. Among other things, these interviews helped reveal some of the context surrounding Ilyenkov’s tragic suicide in 1979 (44, 48).

Reading this book was highly engaging and inspiring in terms of how it makes explicit Ilyenkov’s continued relevance to philosophy, education, and psychology, despite the efforts made during his lifetime to censor, if not bury, his work. The only note of caution that can be raised is that Lotz’ approach to Ilyenkov lacks any significant critical commentary. While there is sufficient attention paid to Ilyenkov’s critics in the diamat state apparatus, this is done largely to emphasize that Ilyenkov was single-minded in his pursuit of good philosophy and willing to challenge calcified and hostile structures of power. Lotz’ treatment of Oittenen could have benefitted from an engagement with Oittenen’s criticisms of Ilyenkov, which are hinted at (39). Further, the book seems to describe Ilyenkov as primarily being focused on epistemology (11-12, 29, 31), whereas, as Oittenen is cited in the book as saying, Ilyenkov ‘stubbornly insisted on the unity— yes, the identity— of dialectics, logics, and the theory of cognition’ (p37). As this hints at, Ilyenkov, in fact, rejected the epistemological focus of his neo-Kantian colleagues, which puts knowledge within the confines of the conditions for the possibility of knowing. The neo-Kantianism that Ilyenkov rails at extensively in his work (cf. Ilyenkov, 2018), puts logic in the mind alone, leaving thought out of touch with the world. By extending logic to dialectics and the theory of cognition, Ilyenkov is in effect unifying epistemology and metaphysics, making logic immanent in the world as a concrete totality. Having said this, it should be noted that the Lotz acknowledges being restricted by space and, therefore, what she could tackle in a slim volume. This should not detract from anyone interested in Marxism, including scholars interested specifically in creative Soviet Marxism and Ilyenkov, from engaging with this illuminating work. This call for a return to Ilyenkov is welcome.

29 August 2019

References

Hegel, G.W.F. 2010 The Science of Logic Trans. G. Di Giovanni, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Ilyenkov, Evald 2018 Lenin’s Idea of the Coincidence of Logic, Theory of Cognition and Dialectics Intelligent Materialism: Essays on Hegel and Dialectics Historical Materialism Book Series, Volume 181, Ed. and Trans. E.V. Pavlov, Leiden: Brill

URL: https://marxandphilosophy.org.uk/reviews/17316_finding-ilyenkov-how-a-soviet-philosopher-who-stood-up-for-dialectics-continues-to-inspire-by-corinna-lotz-reviewed-by-dom-taylor/

This review is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0

PDF OF BOOK

Soviet Psychology: ACTIVITY AND IDEALISM ... - Marxists Internet Archive

https://www.marxists.org › books › ilyenkov › ideal-activity

Evald Vasilyevich Ilyenkov (1924-1979). 1. Philosophy, 2. ... lationship of the material and the ideal in human life. ... process of goal directed human actions.

e-flux Journal #88 - Alexei Penzin - Contingency and Necessity in Evald Ilyenkov’s Communist Cosmology

https://www.e-flux.com/journal/88/174178/contingency-and-necessity-in-evald-ilyenkov-s-communist-cosmology/

Russian Studies in Philosophy, vol. 48, no. 4 (Spring 2010), pp. 63–75.

© 2010 M.E. Sharpe, Inc. All rights reserved.

1061–1967/2010 $9.50 + 0.00.

DOI 10.2753/RSP1061-1967480403

Andrey D. Maidansky

Ascent Toward the Ideal

The article discusses Ilyenkov’s concept of the ideal and its phenomena.

It attempts to reconstruct the authentic meaning assigned to this notion

by the thinker himself as well as to map the directions of contemporary

polemic concerning the concept of the ideal.

The category of the ideal forms the axis about which the thinking of E.V. Ilyenkov always turned. He regarded the ideal and its phenomena as the sole real object of philosophy. Philosophy is the

science of ideas and of the ideal. It has no other object. Throughout

his life, Ilyenkov investigated the category of the ideal, in its various hypostases—the forms of value, personality, and talent and of social ideals—and, of course, in its own logical form

The Ilyenkov Triangle: Marxism in Search of its Philosophical Roots

Andrey Maidansky

Studying the phenomena of the ideal, Evald Ilyenkov checks every important step in his thinking with Hegel and Spinoza. Their philosophical teachings form the foundation for the triangle of “dialectical logic”, at the peak of which is Marx with his method of “ascending to the concrete”. This work will carry out a comparison of the conceptions of Ilyenkov and Western European Marxists along the “Hegel–Spinoza” line.https://www.academia.edu/37220507/The_Ilyenkov_Triangle_Marxism_in_Search_of_its_Philosophical_Roots

The concept of the ideal appeared at the epicentre of the heated controversy between two main trends in post-war Soviet philosophy – practical and somatic materialism. Ilyenkov saw a source of the ideal in labour, defining the ideal as a ‘subjective image of objective reality’. With this, he contested as a reduction of the ideal to functions of brain, as a projection of this concept onto the external nature, as it exists beyond the sphere of practical activity of the social man.

Some quick thoughts about what kind of philosopher Ilyenkov is

The publication of the full version of E.V. Ilyenkov’s Dialectics of the Ideal for the first time in English is a milestone in the re-discovery of creative Soviet materialist dialectics. His focus on the essential and contradictory nature of the Ideal – its origins in transformational social human activity and its objective independent existence – is a powerful tool for understanding the nature of today’s economic, ecological and political crises. We connect the dialectics of the Ideal with Lenin’s conspectus of Hegel’s Science of Logic to outline a process and practice of cognition, ascending from the concrete to the abstract and from there to practice. The paper explores the active nature of the Ideal as a concrete universal in three key aspects of today’s crisis: our place in nature, the value-form of globalised capital and the state and democracy. We show how the conflict between the Ideal and the real generates movements that require systemic change in order to succeed. Finally, we touch on the need for new forms of revolutionary organisation in the light of contemporary conditions.

http://www.aworldtowin.net/resources/Contradictions-within-the-Ideal.html

The publication of the full version of E.V. Ilyenkov’s Dialectics of the Ideal for the first time in English is a milestone in the re-discovery of creative Soviet materialist dialectics. His focus on the essential and contradictory nature of the Ideal – its origins in transformational social human activity and its objective independent existence – is a powerful tool for understanding the nature of today’s economic, ecological and political crises. We connect the dialectics of the Ideal with Lenin’s conspectus of Hegel’s Science of Logic to outline a process and practice of cognition, ascending from the concrete to the abstract and from there to practice. The paper explores the active nature of the Ideal as a concrete universal in three key aspects of today’s crisis: our place in nature, the value-form of globalised capital and the state and democracy. We show how the conflict between the Ideal and the real generates movements that require systemic change in order to succeed. Finally, we touch on the need for new forms of revolutionary organisation in the light of contemporary conditions.

http://www.aworldtowin.net/resources/Contradictions-within-the-Ideal.html

http://www.aworldtowin.net/resources/SpinozaIlyenkovWestern%20Marxism.html

Evald Ilyenkov

http://www.historicalmaterialism.org/node/1180

Evald Ilyenkov (1924–1979), the brilliant Russian philosopher whose suicide in March 1979 was directly linked to his growing isolation and ostracism in more orthodox academic circles in Russia. One source refers to a ‘witch hunt’ against him.

When Ilyenkov wrote his first major work The Dialectic of the Abstract and the Concrete in Marx’s Capital in 1956, the director of the Institute of Philosophy, Fedoseyev, having read the proofs, ordered the type-setting of the book to be destroyed. The Italian publisher Feltrinelli (the ‘red millionaire’, as he was called) got hold of a copy and was about to publish it in Italian (to Fedoseyev’s utter rage!) when the Russians forced Ilyenkov to publish the original but in a drastically reduced form and only after removing the most “Hegelian” passages as well as his criticisms of formal logic. (The Italian translation came out in 1961 and has always been one of my most treasured books.)

On the Italian episode see Maidansky’s excellent article here; http://www.academia.edu/…/The_Dialectical_Logic_of_Evald_Il…

Ilyenkov read Hegel in a materialist way, rejecting both Cartesian dualism and the tedious dichotomies between ‘idealism’ & vulgar (physiological!) materialism which, as Alex Levant says in the link below, he saw as complete dead-ends.

As a student of his said in a recent interview, Ilyenkov “developed the idea of the identity (italics!) of being and thought” as the key aspect of Marx’s dialectic. For Ilyenkov ‘the ideal’ was not something subjective or simply ‘in the head’ but the imprint that humans make on the world through their activity. This gave Marx’s concept of value a wider philosophical basis, one based on a fusion of Spinoza and Hegel. (Maidansky says, ‘His heroes were Spinoza, Hegel and Marx, and as regards music – Richard Wagner. His favourite reading was Orwell’s 1984 ’.)

The whole of Evald Ilyenkov’s philosophical career was marred by bureaucracies determined to clamp down on anything remotely resembling creative intellectual work.

The HM series collection “Dialectics of the Ideal” (after a paper of that name by Ilyenkov) is a good introduction to his philosophical theories. It includes the interesting interview with Mareev cited above as well as discussion of Ilyenkov’s interest in Vygotsky, whose seminal work in developmental psychology, imbued with the same passion for Spinoza and Hegel, was cut prematurely short when he died of TB in 1934.

http://www.brill.com/products/book/dialectics-ideal

DOCUMENTS

On the Coincidence of Logic with Dialectics and the Theory of Knowledge of Materialism

by Evald Ilyenkov

(Jan 01, 2020) MONTHLY REVIEW

Evald Ilyenkov by Mary Skies. From DeviantArt.

This essay by Evald Vasilyevich Ilyenkov (1924–79), “On the Coincidence of Logic with Dialectics and the Theory of Knowledge of Materialism,” was published in his most widely known work, Dialectical Logic: Essays on Its History and Theory (first edition in Russian, 1974). The English translation by H. Campbell Creighton is from the edition published by Progress Publishers, Moscow 1977. In this adapted essay, Ilyenkov discusses the idea of the coincidence of dialectics, logics, and theory of knowledge, which was one of the hallmarks of the Ilyenkovian current in post-Stalin Soviet philosophy. Originally, the idea was jotted down by V. I. Lenin in his Philosophical Notebooks when he was reading G. W. F. Hegel in 1914 and 1915, as a critique against the separation of the theory of knowledge from other fields of philosophy.

Ilyenkov was one of the most important and controversial Soviet Marxist philosophers. He contributed substantially to the Marx Renaissance that emerged in the so-called Thaw Period and aimed at the reconstruction of Marx’s original methodology. In 1960, his first book, The Dialectics of the Abstract and the Concrete in Marx’s “Capital,” was published, to be followed by important articles and studies on the concept of the ideal and on problems of dialectical logic. Ilyenkov was known as an ardent critic of technocratic tendencies in the Soviet Union. He stressed that socialist society should express humanist values and not merely be an engineering project. Although Ilyenkov had constant problems with the Soviet philosophical establishment, which viewed his innovatory ideas with suspicion, he did not regard himself as a dissident and remained a member of the Party. He died by his own hands on March 21, 1979. For more information on Ilyenkov, see: Ilyenkov’s website.

—Vesa Oittinen

- January 2014

- In book: Dialectics of the Ideal: Evald Ilyenkov and Creative Soviet Marxism (pp.125-143)

- Publisher: Brill

- Editors: Alex Levant and Vesa Oittinen

Some quick thoughts about what kind of philosopher Ilyenkov is

Contradictions within the Ideal, mediation and transformation in global capitalist society

By Corinna Lotz, Paul Feldman, Penny Cole and Gerry Gold

A paper given at

Evald Ilyenkov – Prospects and Retrospects in Philosophy and Psychology:

An international symposium arranged by the Aleksanteri Institute and the Centre of Research on Activity, Development and Learning (CRADLE), University of Helsinki

15-16 April 2014

Evald Ilyenkov – Prospects and Retrospects in Philosophy and Psychology:

An international symposium arranged by the Aleksanteri Institute and the Centre of Research on Activity, Development and Learning (CRADLE), University of Helsinki

15-16 April 2014

Abstract

The ‘heretic’ philosopher who challenged Stalinism

Evald Ilyenkov was an important Soviet philosopher who came into conflict with the Stalinist authorities. He developed the ideas of the 17th century philosopher Benedict Spinoza as a way of opposing and exposing the conversion of Marxism into dogma.

A World to Win recently participated in an international conference in Helsinki, presenting a paper on the contemporary significance of both Ilyenkov and Spinoza.

Spinoza, Ilyenkov & Western Marxism – meeting the challenges of the global crisis

Corinna Lotz and Penny Cole

Introduction

Evald Ilyenkov took Spinoza’s philosophy as the starting point for his own critique of positivism and mechanical materialism. While this assumed a strictly philosophical form, its political source was Ilyenkov’s profound conviction that a turn towards materialist dialectics was critical for the future of the Soviet Union.

Ilyenkov’s position as an “orthodox heretic” [1] philosopher may help to explain why he identified so closely with Benedict Spinoza. Like Spinoza some 300 years earlier, he was a child of his time, but in equally deep conflict with proponents of dogma. In Spinoza’s case it was religious dogma, in both its Judaic and Christian forms. With Ilyenkov it was Marxist dogma turned into a state religion through Stalinism – and dogma’s ugly sister – the mechanistic positivist scientism which invaded Soviet philosophy during the 1960s. [2]

Ilyenkov championed those sides of the 17th century philosopher’s ideas which made a decisive impact in the late 18th century on Hölderlin and Hegel, and later on Feuerbach, Marx and Engels. He drew on Lenin to establish materialist dialectics once again as the theory of knowledge of Marxism. Like Lenin, Ilyenkov found himself swimming against the tide but was not deflected from his goals.

A renewed interest in Spinoza is blossoming internationally. Historical research is shedding light on Spinoza’s circles and the connection between the political-religious conflicts in the Dutch Republic and his role as “the philosopher of modernity”. [3] The significance of Spinoza for political practice in the present conjuncture has become a rich and contentious arena in philosophy. A number of thinkers, in particular, theorisers of contemporary globalisation such as Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt, have based their ideas on aspects of Spinoza’s Ethics, his Theological Political Treatise and the Political Treatise.

Negri’s espousal of Spinoza has its critics. We will argue that Negri bases his theorising on Spinoza’s mystical and static aspects as part of his rejection of the dialectical and objective implications of Spinoza’s monism, which are precisely those sides which Ilyenkov championed and developed. While the post-structuralist critique of “Modernity” recognises and diagnoses the transformations of subjectivity, it idealises the possibility of contradiction-free transition. This results in an impoverished reading of Spinoza which tends to make resistance into a fixture within an eternal framework. Like the poor, resistance will always be with us.

The abjuring of the concepts of dialectical negation, transformation and the possibility of qualitative leaps leads to an eternalising, timeless “antagonism” thereby re-introducing the metaphysical duality which Spinoza resolved through his concept of substance. Spinozan-Ilyenkovian dialectics offers a path beyond the impasse of 21st century philosophy. Understanding the dialectics of contemporary globalisation and its crisis creates the ground for transforming the ideal into the real.http://www.aworldtowin.net/resources/SpinozaIlyenkovWestern%20Marxism.html

Evald Ilyenkov

http://www.historicalmaterialism.org/node/1180

Evald Ilyenkov (1924–1979), the brilliant Russian philosopher whose suicide in March 1979 was directly linked to his growing isolation and ostracism in more orthodox academic circles in Russia. One source refers to a ‘witch hunt’ against him.

When Ilyenkov wrote his first major work The Dialectic of the Abstract and the Concrete in Marx’s Capital in 1956, the director of the Institute of Philosophy, Fedoseyev, having read the proofs, ordered the type-setting of the book to be destroyed. The Italian publisher Feltrinelli (the ‘red millionaire’, as he was called) got hold of a copy and was about to publish it in Italian (to Fedoseyev’s utter rage!) when the Russians forced Ilyenkov to publish the original but in a drastically reduced form and only after removing the most “Hegelian” passages as well as his criticisms of formal logic. (The Italian translation came out in 1961 and has always been one of my most treasured books.)

On the Italian episode see Maidansky’s excellent article here; http://www.academia.edu/…/The_Dialectical_Logic_of_Evald_Il…

Ilyenkov read Hegel in a materialist way, rejecting both Cartesian dualism and the tedious dichotomies between ‘idealism’ & vulgar (physiological!) materialism which, as Alex Levant says in the link below, he saw as complete dead-ends.

As a student of his said in a recent interview, Ilyenkov “developed the idea of the identity (italics!) of being and thought” as the key aspect of Marx’s dialectic. For Ilyenkov ‘the ideal’ was not something subjective or simply ‘in the head’ but the imprint that humans make on the world through their activity. This gave Marx’s concept of value a wider philosophical basis, one based on a fusion of Spinoza and Hegel. (Maidansky says, ‘His heroes were Spinoza, Hegel and Marx, and as regards music – Richard Wagner. His favourite reading was Orwell’s 1984 ’.)

The whole of Evald Ilyenkov’s philosophical career was marred by bureaucracies determined to clamp down on anything remotely resembling creative intellectual work.

The HM series collection “Dialectics of the Ideal” (after a paper of that name by Ilyenkov) is a good introduction to his philosophical theories. It includes the interesting interview with Mareev cited above as well as discussion of Ilyenkov’s interest in Vygotsky, whose seminal work in developmental psychology, imbued with the same passion for Spinoza and Hegel, was cut prematurely short when he died of TB in 1934.

http://www.brill.com/products/book/dialectics-ideal

DOCUMENTS

On the Coincidence of Logic with Dialectics and the Theory of Knowledge of Materialism

by Evald Ilyenkov

(Jan 01, 2020) MONTHLY REVIEW

Evald Ilyenkov by Mary Skies. From DeviantArt.

This essay by Evald Vasilyevich Ilyenkov (1924–79), “On the Coincidence of Logic with Dialectics and the Theory of Knowledge of Materialism,” was published in his most widely known work, Dialectical Logic: Essays on Its History and Theory (first edition in Russian, 1974). The English translation by H. Campbell Creighton is from the edition published by Progress Publishers, Moscow 1977. In this adapted essay, Ilyenkov discusses the idea of the coincidence of dialectics, logics, and theory of knowledge, which was one of the hallmarks of the Ilyenkovian current in post-Stalin Soviet philosophy. Originally, the idea was jotted down by V. I. Lenin in his Philosophical Notebooks when he was reading G. W. F. Hegel in 1914 and 1915, as a critique against the separation of the theory of knowledge from other fields of philosophy.

Ilyenkov was one of the most important and controversial Soviet Marxist philosophers. He contributed substantially to the Marx Renaissance that emerged in the so-called Thaw Period and aimed at the reconstruction of Marx’s original methodology. In 1960, his first book, The Dialectics of the Abstract and the Concrete in Marx’s “Capital,” was published, to be followed by important articles and studies on the concept of the ideal and on problems of dialectical logic. Ilyenkov was known as an ardent critic of technocratic tendencies in the Soviet Union. He stressed that socialist society should express humanist values and not merely be an engineering project. Although Ilyenkov had constant problems with the Soviet philosophical establishment, which viewed his innovatory ideas with suspicion, he did not regard himself as a dissident and remained a member of the Party. He died by his own hands on March 21, 1979. For more information on Ilyenkov, see: Ilyenkov’s website.

—Vesa Oittinen

LONG READ

https://monthlyreview.org/2020/01/01/on-the-coincidence-of-logic-with-dialectics-and-the-theory-of-knowledge-of-materialism/

INTERVIEW

Evald Ilyenkov and Soviet Philosophy

by Andrey Maidansky and Vesa Oittinen

(Jan 01, 2020) MONTHLY REVIEW

Evald Ilyenkov's philosophy revisited by Vesa Oittinen.

Andrey Maidansky is a professor of philosophy at the University of Belgorod, Russia. He has published, in Russian, many books and articles on Baruch Spinoza, Marxism, and history of Soviet philosophy. One of his main interests is the well-known and controversial Soviet philosopher Evald Ilyenkov (1924–79), who left behind a vast archive of unpublished materials that will be published in a ten-volume collection edited by Maidansky.

Vesa Oittinen is a professor at the Aleksanteri Institute, University of Helsinki, Finland. He and Maidansky are longtime collaborators. They edited a book together on the activity approach in Soviet philosophy of the 1960s and ’70s, The Practical Essence of Man: The “Activity Approach” in Late Soviet Philosophy (Haymarket Books, 2017).

Vesa Oittinen: The Soviet philosopher Evald Ilyenkov died in 1979. Since then, his fame has steadily grown, slowly at first, but he has received increasing international attention in the last few years. How would you explain this phenomenon? After all, Soviet philosophy in general has the reputation of being rather dull.

Andrey Maidansky: Indeed, Ilyenkov’s popularity has been growing, especially over the last ten to fifteen years, while the rest of Soviet Marxism (with the exception of Lev Vygotsky’s cultural-historical psychology) has practically turned into a museum piece. Almost every year we see new translations of Ilyenkov’s works, especially into English and Spanish. Recently, in Western Europe, the International Friends of Ilyenkov group was formed (their second symposium was held in Copenhagen the summer of 2018).

I believe that two main factors contribute to the growing attraction of Ilyenkov’s works.

First is a new wave of interest in Karl Marx and creative Marxism around the world, against a background of rapid social transformation, expectations of another economic crisis, and so on. And Ilyenkov managed to take the best from Marx—that is, Marx’s method of thinking and his critical spirit. In Ilyenkov’s work, there is minimal ideological veiling and scholasticism, which turns many intelligent people away from Marxism.Secondly, there remained many texts in Ilyenkov’s archive that he could not publish during his lifetime, and they were sometimes even more interesting than his published works. Here, I would mention his impressive Cosmology of the Spirit (which was recently translated into German and English for the first time); his writings on psychology and pedagogy; his study of the phenomenon of alienation of man in modern society (his critique of machine-like socialism is especially interesting); and his quest for historical ways of shedding alienation. The flow of publications of Ilyenkov’s manuscripts has continued unabated, rousing public curiosity. More than half of his handwritten heritage remained on his desk. He had not managed to print even his cherished Dialectics of the Ideal.

VO: You mentioned the Cultural-Historical School of Soviet psychology (Aleksey Leontiev, Lev Vygotsky). Indeed, it seems that Ilyenkov was in many respects close to this school. The common ground between them was the theory of activity, or activity approach as it was called.

AM: Yes, Ilyenkov considered himself a champion of this powerful school in psychology. He wrote about “the superiority of Vygotsky’s school over any other scheme of explaining the psyche,” explicitly associating himself with this school. Ilyenkov worked along the lines of Leontiev and Petr Galperin’s activity theory. This is one of the branches of Vygotsky’s school, which presents the psyche as a form of search and orienting activity in the outside world. In the case of human beings, this activity is performed in the world of cultural objects, artifacts, created by human labor.

Ilyenkov was especially interested in the process of interiorization—the mechanics of enrooting (Vygotsky’s term) cultural functions within the individual (initially a nonhuman animal) psyche. At that moment, a human personality, or an own self, arises. This subtle process is seen especially clearly, as in a slow-motion film, in the Zagorsk experiment with deaf-blind children. Ilyenkov devoted more than ten years of his life to this experiment. After his tragic death (he committed suicide in 1979), his deaf-blind student Sasha Suvorov wrote a poem-dialogue, “The Focus of Pain,” about her teacher and another student, Natasha Korneeva, named her daughter Evaldina.

VO: Despite these affinities to the Soviet cultural-historical psychology, Ilyenkov was not a psychologist, but a philosopher. I believe we might say that it was he who started the activity approach in Soviet philosophy, an approach that previously was applied only in psychology?

AM: Ilyenkov was primarily a philosopher, of course, and in the field of psychology he dealt mainly with the problems of general methodological order: how the psyche is formed and what its primary “germ cell” is, what personality is, and so on.

As for the activity approach, it was formally declared in textbooks of Marxist philosophy, with relevant quotes from Marx’s Theses on Feuerbach about objective-practical activity and the need not only to interpret the world but to change it. The term activity approach is not used in textbooks, but Ilyenkov did not use it either (activity as an adjective, dejatel’nostnyj, does not occur in his works at all). Nonetheless, it was Ilyenkov who first turned his attention to the challenge of explaining the genesis and structure of human thought on the basis of objective activity—labor.

In the most general terms, the case appeared to him as follows. Human labor, as it were, turns natural phenomena inside out, revealing in practice the pure (ideal) forms of things. And only afterward, these forms, melted in the “retort of civilization,” imprint themselves on the human mind as “ideas.” The practical changing of the world serves as the basis and source of both artistic perception and logical thought, as well as of all specifically human abilities.

This principle was adopted by Ilyenkov’s talented students—Yury Davydov, Lev Naumenko, Genrikh Batishchev, and some others. Unfortunately, their main works were not translated into foreign languages. An English reader can get an idea of them perhaps, but only from the book we edited a couple of years ago.

VO: Ilyenkov thus was not only a professional philosopher, but also wanted his ideas concerning the role of activity in education to be applied widely in Soviet society. Here, we can see a union of theory and practice.

AM: It is true, Ilyenkov never was an armchair philosopher. During the Second World War, he served as an artilleryman, in peacetime he designed radio devices (including a huge tape recorder with excellent sound quality), and even installed a lathe in his study. He also worked a lot on economics and pedagogical psychology.

Ilyenkov was tormented by the question: Why did the state not wither away in the socialist countries, contrary to Marx’s prediction? Why does society not evolve into a self-governing commune? On the contrary, the power of the state over the human personality grew tremendously. Ilyenkov concluded that in order to build a society with a so-called human face, human personality itself had to be transformed. Hence his keen interest in the Zagorsk experiment with deaf-blind children, in which the principles of nurturing a new kind of personality could be honed and tested in practice. Cultural-historical psychology and developing pedagogy should teach us how to form a harmonious personality, one that could shed the yoke of megamachines of alienation—the state and the market.

Someone might call it a pedagogical utopia. Maybe. But, as Oscar Wilde said, “a map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which Humanity is always landing.”

VO: Seen from today’s perspective, Ilyenkov’s most original contribution to Marxist philosophy was perhaps the concept of the ideal, a concept that has since then been much debated.

AM: The 1962 publication of Ilyenkov’s article “The Ideal” in the Philosophical Encyclopedia caused a huge upsurge of controversy in the Soviet philosophical community. The ideological iron curtain prevented discussion of it reaching beyond the Soviet Union. Ilyenkov’s most important work on that subject was fully translated into English only quite recently and published in Dialectics of the Ideal, with comments clarifying the polemical context around the notion of the ideal.

The fate of this late manuscript was not simple. The director of the Institute of Philosophy, a former Communist Party official Boris Ukraintsev, did not allow Dialectics of the Ideal to be printed for several years. The manuscript was published only posthumously, after being abridged and under a modified title. So, Dialectics of the Ideal brought Roland Barthes’s hyperbole into practice: the reader’s birth had to be paid for by the death of the author.

This 1979 publication heaped fuel on the controversy around the concept of the ideal. Mikhail Lifshits, a coryphaeus of Soviet aesthetics, joined in the dispute. Ilyenkov treated Lifshits with great respect. (By the way, Lifshits was also a close friend of Georg Lukács.) Lifshits spoke out against the activity understanding of the ideal. According to him, the concept of the ideal sets a standard of perfection for anything and is applicable to all and everything in nature.

For his part, Ilyenkov saw in the ideal “a kind of stamp impressed on the substance of nature by social human life-activity.” Everything that falls within the circle of this life activity receives the “stamp” of ideality, becoming (while the activity persists) a dwelling place and a tool of the ideal. The cerebral cortex becomes an instrument of thought, silver and gold become money, and fire appears to be the deity of the hearth. Even the stars in the sky turn into zodiac signs, into a compass and a calendar. Ilyenkov calls the ideal a “relationship of representation” of things (of their inner essences and laws of existence, to be more precise) within the compass of human activity, within the process of producing social life.

Ilyenkov was deeply interested in the problem of ideal social order. In his book On Idols and Ideals (1968), he attempted to draw the vector of the communist movement in the modern world. He understood communism as the process of transferring the functions of managing social life into the hands of individual people, or, in other words, as the process of replacing the market and state machines with a “self-governing organization.” The young Marx called it the “removal of alienation” and the “reappropriation of man” (der menschlichen Wiedergewinnung).

To Ilyenkov’s chagrin, that very “cybernetic nightmare,” the idol of the Machine that so terrified him, appeared in the Soviet Union under the guise of the communist ideal. It was a machine-like socialism that was built in the country, instead of a society “with a human face.” I believe this undermined his will to live. George Orwell’s 1984 (which was banned in the Soviet Union) became his favorite book. Ilyenkov read it in German and even translated it into Russian for personal use.

VO: Ilyenkov had the reputation of being a Hegelian Marxist. It seems to me, however, that he was not the same kind of Hegelian as, for example, the Abram Deborin school of the 1920s in early Soviet philosophy. Maybe we could compare him with Lukács?

AM: As a philosopher, Ilyenkov grew up with Hegel’s books. He was deeply impressed by Hegel’s pamphlet Who Thinks Abstractly? He translated and commented on it twice in twenty years. At the same time, he reproached Hegel for thinking too abstractly—namely, for turning dialectic formulas into “a priori outlines” and for a “haughty and slighting attitude towards the world of empirically given facts, events, phenomena.” The leading lights of dialectical materialism (Ilyenkov mentions the names of Georgi Plekhanov, Joseph Stalin, and Mao Zedong) inherited this original sin of idealism from Hegel.

Ilyenkov made a similar rebuke against Plekhanov’s followers led by Deborin. These people created school courses of diamat and histmat (short for dialectical and historical materialism), which nauseated Ilyenkov. In Western literature, it is often claimed that Ilyenkov continued Deborin’s line in Marxist philosophy. Such opinion seems incorrect to me, although I do not deny the affinity between the two in their understanding of the subject of philosophy and certain categories of dialectics, as well as the fact that they have common sympathies for Hegel and Spinoza.

Lukács is quite another matter. Ilyenkov valued his book Young Hegel and the Problems of Capitalist Society very highly; he translated and commented on it jointly with his students. In Ilyenkov’s archive, his review of Lukács’s Ontology of Social Being, from the early 1970s, is preserved. It is written with great respect for Lukács, who died in 1971, despite the fact that Ilyenkov was an implacable opponent of the ontologization of dialectics. In his eyes, Lukács is a representative of the best, most vibrant Marxist tradition, in contrast to the stillborn scholasticism of diamat.

VO: You are at present editing the Collected Works of Ilyenkov. Could you tell me a bit more about this publication project? It would also be interesting to know whether the unpublished material from the Ilyenkov archive will affect the hitherto established image of his philosophy.

AM: In February 2019, the first of ten volumes of Ilyenkov’s Collected Works appeared in Russian. We have prepared three more volumes for printing. Academic Vladislav Lektorsky, Ilyenkov’s daughter Elena Illesh, and I worked on them.

Publication of the remaining materials from the Ilyenkov’s archive may add certain new features to his portrait, but it is unlikely to affect his current image significantly. The main part of his archive has already been published. Among the still unpublished works, I would single out the manuscript of his final book, which criticizes the technocratic project of building socialism, which Ilyenkov believed was being carried out in the Soviet Union. Since he was not allowed to criticize actual machine socialism directly, Ilyenkov argued with its ideologues, such as Alexander Bogdanov (V. I. Lenin’s closest ally, up to a certain period, and his opponent in philosophy) and the contemporary Polish Marxist Adam Schaff.

However, Soviet censorship tightly blocked everything that was written by Ilyenkov on this topic. Only a year after his death was his last book published—and even so, in a heavily censored form and under a title chosen by some censor: Leninist Dialectics and the Metaphysics of Positivism.

VO: Yet a final and inevitable question: Do you see any lacunae or problematic points in Ilyenkov’s philosophy?

AM: Great thinkers, like Ilyenkov, make intelligent mistakes. Their mistakes provide valuable material for reflection and indicate the growth points of a theory. That is, they are objective mistakes, conditioned by the spirit of the times and by contradictions in the very object of research, and not by a subjective weakness of the mind.

There are problems over which Ilyenkov cudgeled his brain long and hard, but could not cope with—such as, for example, the already mentioned withering away of the state. And the most serious lacuna can be found in that area. Ilyenkov frequently and wittily criticized the idea of designing a “Machine smarter than man,” that is, a supercomputer capable of planning economic development and managing social life better than living people. However, he never raised the obvious (for Marxists) question: How can a programmable electronic machine help us in “removing alienation” and the “reappropriation of man”? If “the hand-mill gives you society with the feudal lord; the steam-mill society with the industrial capitalist” (Marx), then what society does a computer-based mill give us?

To me, personally, the mental arguments with Ilyenkov are especially interesting and useful. The concept of “thinking body,” which Ilyenkov attributed to Spinoza, seems to me inadequate and confused (I had to wage a fierce debate with Ilyenkov’s students about that concept). Or, quite recently, in the pages of Mind, Culture, and Activity, I defended Vygotsky’s view of affect as a “germ cell” of psyche against Ilyenkov’s position, which considered sense image as such a “cell.” But even in such cases, I am accustomed to viewing things through lenses of logical categories polished by Ilyenkov. I have yet to encounter better theoretical optics.

INTERVIEW

Evald Ilyenkov and Soviet Philosophy

by Andrey Maidansky and Vesa Oittinen

(Jan 01, 2020) MONTHLY REVIEW

Evald Ilyenkov's philosophy revisited by Vesa Oittinen.

Andrey Maidansky is a professor of philosophy at the University of Belgorod, Russia. He has published, in Russian, many books and articles on Baruch Spinoza, Marxism, and history of Soviet philosophy. One of his main interests is the well-known and controversial Soviet philosopher Evald Ilyenkov (1924–79), who left behind a vast archive of unpublished materials that will be published in a ten-volume collection edited by Maidansky.

Vesa Oittinen is a professor at the Aleksanteri Institute, University of Helsinki, Finland. He and Maidansky are longtime collaborators. They edited a book together on the activity approach in Soviet philosophy of the 1960s and ’70s, The Practical Essence of Man: The “Activity Approach” in Late Soviet Philosophy (Haymarket Books, 2017).

Vesa Oittinen: The Soviet philosopher Evald Ilyenkov died in 1979. Since then, his fame has steadily grown, slowly at first, but he has received increasing international attention in the last few years. How would you explain this phenomenon? After all, Soviet philosophy in general has the reputation of being rather dull.

Andrey Maidansky: Indeed, Ilyenkov’s popularity has been growing, especially over the last ten to fifteen years, while the rest of Soviet Marxism (with the exception of Lev Vygotsky’s cultural-historical psychology) has practically turned into a museum piece. Almost every year we see new translations of Ilyenkov’s works, especially into English and Spanish. Recently, in Western Europe, the International Friends of Ilyenkov group was formed (their second symposium was held in Copenhagen the summer of 2018).

I believe that two main factors contribute to the growing attraction of Ilyenkov’s works.

First is a new wave of interest in Karl Marx and creative Marxism around the world, against a background of rapid social transformation, expectations of another economic crisis, and so on. And Ilyenkov managed to take the best from Marx—that is, Marx’s method of thinking and his critical spirit. In Ilyenkov’s work, there is minimal ideological veiling and scholasticism, which turns many intelligent people away from Marxism.Secondly, there remained many texts in Ilyenkov’s archive that he could not publish during his lifetime, and they were sometimes even more interesting than his published works. Here, I would mention his impressive Cosmology of the Spirit (which was recently translated into German and English for the first time); his writings on psychology and pedagogy; his study of the phenomenon of alienation of man in modern society (his critique of machine-like socialism is especially interesting); and his quest for historical ways of shedding alienation. The flow of publications of Ilyenkov’s manuscripts has continued unabated, rousing public curiosity. More than half of his handwritten heritage remained on his desk. He had not managed to print even his cherished Dialectics of the Ideal.

VO: You mentioned the Cultural-Historical School of Soviet psychology (Aleksey Leontiev, Lev Vygotsky). Indeed, it seems that Ilyenkov was in many respects close to this school. The common ground between them was the theory of activity, or activity approach as it was called.

AM: Yes, Ilyenkov considered himself a champion of this powerful school in psychology. He wrote about “the superiority of Vygotsky’s school over any other scheme of explaining the psyche,” explicitly associating himself with this school. Ilyenkov worked along the lines of Leontiev and Petr Galperin’s activity theory. This is one of the branches of Vygotsky’s school, which presents the psyche as a form of search and orienting activity in the outside world. In the case of human beings, this activity is performed in the world of cultural objects, artifacts, created by human labor.

Ilyenkov was especially interested in the process of interiorization—the mechanics of enrooting (Vygotsky’s term) cultural functions within the individual (initially a nonhuman animal) psyche. At that moment, a human personality, or an own self, arises. This subtle process is seen especially clearly, as in a slow-motion film, in the Zagorsk experiment with deaf-blind children. Ilyenkov devoted more than ten years of his life to this experiment. After his tragic death (he committed suicide in 1979), his deaf-blind student Sasha Suvorov wrote a poem-dialogue, “The Focus of Pain,” about her teacher and another student, Natasha Korneeva, named her daughter Evaldina.

VO: Despite these affinities to the Soviet cultural-historical psychology, Ilyenkov was not a psychologist, but a philosopher. I believe we might say that it was he who started the activity approach in Soviet philosophy, an approach that previously was applied only in psychology?

AM: Ilyenkov was primarily a philosopher, of course, and in the field of psychology he dealt mainly with the problems of general methodological order: how the psyche is formed and what its primary “germ cell” is, what personality is, and so on.

As for the activity approach, it was formally declared in textbooks of Marxist philosophy, with relevant quotes from Marx’s Theses on Feuerbach about objective-practical activity and the need not only to interpret the world but to change it. The term activity approach is not used in textbooks, but Ilyenkov did not use it either (activity as an adjective, dejatel’nostnyj, does not occur in his works at all). Nonetheless, it was Ilyenkov who first turned his attention to the challenge of explaining the genesis and structure of human thought on the basis of objective activity—labor.

In the most general terms, the case appeared to him as follows. Human labor, as it were, turns natural phenomena inside out, revealing in practice the pure (ideal) forms of things. And only afterward, these forms, melted in the “retort of civilization,” imprint themselves on the human mind as “ideas.” The practical changing of the world serves as the basis and source of both artistic perception and logical thought, as well as of all specifically human abilities.

This principle was adopted by Ilyenkov’s talented students—Yury Davydov, Lev Naumenko, Genrikh Batishchev, and some others. Unfortunately, their main works were not translated into foreign languages. An English reader can get an idea of them perhaps, but only from the book we edited a couple of years ago.

VO: Ilyenkov thus was not only a professional philosopher, but also wanted his ideas concerning the role of activity in education to be applied widely in Soviet society. Here, we can see a union of theory and practice.

AM: It is true, Ilyenkov never was an armchair philosopher. During the Second World War, he served as an artilleryman, in peacetime he designed radio devices (including a huge tape recorder with excellent sound quality), and even installed a lathe in his study. He also worked a lot on economics and pedagogical psychology.

Ilyenkov was tormented by the question: Why did the state not wither away in the socialist countries, contrary to Marx’s prediction? Why does society not evolve into a self-governing commune? On the contrary, the power of the state over the human personality grew tremendously. Ilyenkov concluded that in order to build a society with a so-called human face, human personality itself had to be transformed. Hence his keen interest in the Zagorsk experiment with deaf-blind children, in which the principles of nurturing a new kind of personality could be honed and tested in practice. Cultural-historical psychology and developing pedagogy should teach us how to form a harmonious personality, one that could shed the yoke of megamachines of alienation—the state and the market.

Someone might call it a pedagogical utopia. Maybe. But, as Oscar Wilde said, “a map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which Humanity is always landing.”

VO: Seen from today’s perspective, Ilyenkov’s most original contribution to Marxist philosophy was perhaps the concept of the ideal, a concept that has since then been much debated.

AM: The 1962 publication of Ilyenkov’s article “The Ideal” in the Philosophical Encyclopedia caused a huge upsurge of controversy in the Soviet philosophical community. The ideological iron curtain prevented discussion of it reaching beyond the Soviet Union. Ilyenkov’s most important work on that subject was fully translated into English only quite recently and published in Dialectics of the Ideal, with comments clarifying the polemical context around the notion of the ideal.

The fate of this late manuscript was not simple. The director of the Institute of Philosophy, a former Communist Party official Boris Ukraintsev, did not allow Dialectics of the Ideal to be printed for several years. The manuscript was published only posthumously, after being abridged and under a modified title. So, Dialectics of the Ideal brought Roland Barthes’s hyperbole into practice: the reader’s birth had to be paid for by the death of the author.

This 1979 publication heaped fuel on the controversy around the concept of the ideal. Mikhail Lifshits, a coryphaeus of Soviet aesthetics, joined in the dispute. Ilyenkov treated Lifshits with great respect. (By the way, Lifshits was also a close friend of Georg Lukács.) Lifshits spoke out against the activity understanding of the ideal. According to him, the concept of the ideal sets a standard of perfection for anything and is applicable to all and everything in nature.

For his part, Ilyenkov saw in the ideal “a kind of stamp impressed on the substance of nature by social human life-activity.” Everything that falls within the circle of this life activity receives the “stamp” of ideality, becoming (while the activity persists) a dwelling place and a tool of the ideal. The cerebral cortex becomes an instrument of thought, silver and gold become money, and fire appears to be the deity of the hearth. Even the stars in the sky turn into zodiac signs, into a compass and a calendar. Ilyenkov calls the ideal a “relationship of representation” of things (of their inner essences and laws of existence, to be more precise) within the compass of human activity, within the process of producing social life.

Ilyenkov was deeply interested in the problem of ideal social order. In his book On Idols and Ideals (1968), he attempted to draw the vector of the communist movement in the modern world. He understood communism as the process of transferring the functions of managing social life into the hands of individual people, or, in other words, as the process of replacing the market and state machines with a “self-governing organization.” The young Marx called it the “removal of alienation” and the “reappropriation of man” (der menschlichen Wiedergewinnung).

To Ilyenkov’s chagrin, that very “cybernetic nightmare,” the idol of the Machine that so terrified him, appeared in the Soviet Union under the guise of the communist ideal. It was a machine-like socialism that was built in the country, instead of a society “with a human face.” I believe this undermined his will to live. George Orwell’s 1984 (which was banned in the Soviet Union) became his favorite book. Ilyenkov read it in German and even translated it into Russian for personal use.

VO: Ilyenkov had the reputation of being a Hegelian Marxist. It seems to me, however, that he was not the same kind of Hegelian as, for example, the Abram Deborin school of the 1920s in early Soviet philosophy. Maybe we could compare him with Lukács?

AM: As a philosopher, Ilyenkov grew up with Hegel’s books. He was deeply impressed by Hegel’s pamphlet Who Thinks Abstractly? He translated and commented on it twice in twenty years. At the same time, he reproached Hegel for thinking too abstractly—namely, for turning dialectic formulas into “a priori outlines” and for a “haughty and slighting attitude towards the world of empirically given facts, events, phenomena.” The leading lights of dialectical materialism (Ilyenkov mentions the names of Georgi Plekhanov, Joseph Stalin, and Mao Zedong) inherited this original sin of idealism from Hegel.

Ilyenkov made a similar rebuke against Plekhanov’s followers led by Deborin. These people created school courses of diamat and histmat (short for dialectical and historical materialism), which nauseated Ilyenkov. In Western literature, it is often claimed that Ilyenkov continued Deborin’s line in Marxist philosophy. Such opinion seems incorrect to me, although I do not deny the affinity between the two in their understanding of the subject of philosophy and certain categories of dialectics, as well as the fact that they have common sympathies for Hegel and Spinoza.

Lukács is quite another matter. Ilyenkov valued his book Young Hegel and the Problems of Capitalist Society very highly; he translated and commented on it jointly with his students. In Ilyenkov’s archive, his review of Lukács’s Ontology of Social Being, from the early 1970s, is preserved. It is written with great respect for Lukács, who died in 1971, despite the fact that Ilyenkov was an implacable opponent of the ontologization of dialectics. In his eyes, Lukács is a representative of the best, most vibrant Marxist tradition, in contrast to the stillborn scholasticism of diamat.

VO: You are at present editing the Collected Works of Ilyenkov. Could you tell me a bit more about this publication project? It would also be interesting to know whether the unpublished material from the Ilyenkov archive will affect the hitherto established image of his philosophy.

AM: In February 2019, the first of ten volumes of Ilyenkov’s Collected Works appeared in Russian. We have prepared three more volumes for printing. Academic Vladislav Lektorsky, Ilyenkov’s daughter Elena Illesh, and I worked on them.

Publication of the remaining materials from the Ilyenkov’s archive may add certain new features to his portrait, but it is unlikely to affect his current image significantly. The main part of his archive has already been published. Among the still unpublished works, I would single out the manuscript of his final book, which criticizes the technocratic project of building socialism, which Ilyenkov believed was being carried out in the Soviet Union. Since he was not allowed to criticize actual machine socialism directly, Ilyenkov argued with its ideologues, such as Alexander Bogdanov (V. I. Lenin’s closest ally, up to a certain period, and his opponent in philosophy) and the contemporary Polish Marxist Adam Schaff.

However, Soviet censorship tightly blocked everything that was written by Ilyenkov on this topic. Only a year after his death was his last book published—and even so, in a heavily censored form and under a title chosen by some censor: Leninist Dialectics and the Metaphysics of Positivism.

VO: Yet a final and inevitable question: Do you see any lacunae or problematic points in Ilyenkov’s philosophy?

AM: Great thinkers, like Ilyenkov, make intelligent mistakes. Their mistakes provide valuable material for reflection and indicate the growth points of a theory. That is, they are objective mistakes, conditioned by the spirit of the times and by contradictions in the very object of research, and not by a subjective weakness of the mind.

There are problems over which Ilyenkov cudgeled his brain long and hard, but could not cope with—such as, for example, the already mentioned withering away of the state. And the most serious lacuna can be found in that area. Ilyenkov frequently and wittily criticized the idea of designing a “Machine smarter than man,” that is, a supercomputer capable of planning economic development and managing social life better than living people. However, he never raised the obvious (for Marxists) question: How can a programmable electronic machine help us in “removing alienation” and the “reappropriation of man”? If “the hand-mill gives you society with the feudal lord; the steam-mill society with the industrial capitalist” (Marx), then what society does a computer-based mill give us?

To me, personally, the mental arguments with Ilyenkov are especially interesting and useful. The concept of “thinking body,” which Ilyenkov attributed to Spinoza, seems to me inadequate and confused (I had to wage a fierce debate with Ilyenkov’s students about that concept). Or, quite recently, in the pages of Mind, Culture, and Activity, I defended Vygotsky’s view of affect as a “germ cell” of psyche against Ilyenkov’s position, which considered sense image as such a “cell.” But even in such cases, I am accustomed to viewing things through lenses of logical categories polished by Ilyenkov. I have yet to encounter better theoretical optics.

No comments:

Post a Comment