Final resting place of Sequoyah never found, but his impact on Cherokee culture remains

By Grant D. Crawford

Sep 23, 2020

Hunter Hodson examines the statue of Sequoyah in Northeastern State University's Centennial Plaza.

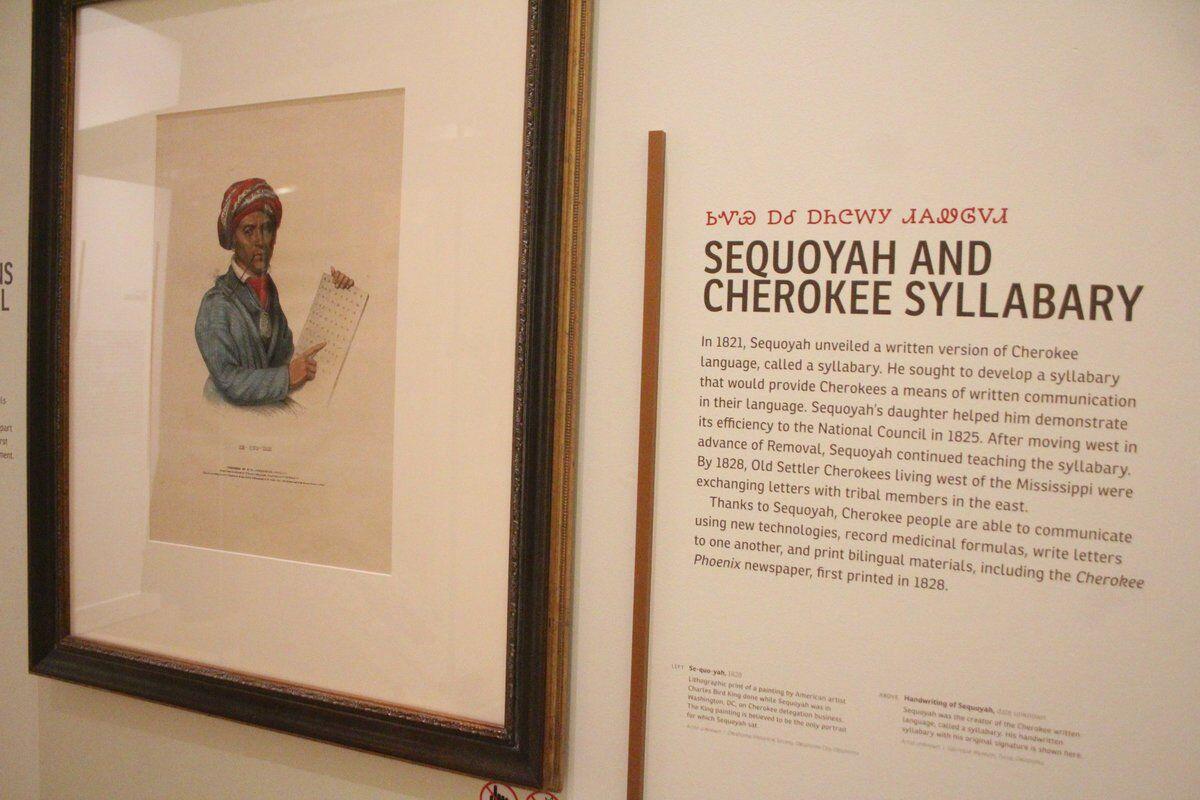

Among the pieces at the Cherokee Nation History Museum is a lithographic print of a painting by American artist Charles Bird King done while Sequoyah was in Washington, D.C., on Cherokee delegation business.

Grant Crawford

The final resting place of perhaps the most famous Cherokee has never been officially confirmed, but the impact he made on Cherokee culture is still in full effect today.

Best known for his creation of the Cherokee syllabary, Sequoyah was also considered a statesman and diplomat of the Cherokee Nation. His gravesite has never been formally identified, although people in the past have claimed to have found his remains. What was documented is his trip to Mexico, from which he never returned.

In the summer of 1842, Sequoyah and his son, Teesy, along with a group of Cherokees ventured to Mexico in search of Cherokees they believed had migrated that far south. According to a Cherokee man, The Worm, and a letter written to the Red River Trading Post from the Cherokees who were living in Mexico, Sequoyah died in the summer of 1843.

"I can't really guess what was on his mind leading up to leaving for Mexico, but obviously he felt passionate about finding those Cherokees who had migrated so far away from the rest of us," said Krystan Moser, cultural collections and exhibit manager for Cherokee Nation Cultural Tourism. "According to the account, he sought to bring them back and to unite them with the rest of the tribe. At least that's what we know based off the documentation we have."

It is believed that Sequoyah, also known by his English name George Guess, was buried somewhere near San Fernando Valley, but that has never been confirmed. The statement made by The Worm and the letter from the Cherokees differed in that regard. But by both accounts, it is understood the syllabary creator died after becoming ill.

"One thing to keep in mind, because we don't know exactly when he was born, he was between the ages of 70 and 80 when he made this trip," said Moser. "Both accounts state that he died of sickness and that he was buried in an unmarked grave."

News of Sequoyah's death didn't reached the Cherokee Nation until 1845, two years after. However, because nobody had heard from him in at least a year, it was believed that he died or that something happened preventing him from returning. So in 1843, the Cherokee Nation National Council passed two laws that benefited his family.

"They had put all of the salt operations into the Cherokee Nation's names, except for Sequoyah's," said Moser. "So his would still be his family's operation to generate income. Also, they granted a literary pension that would be issued to him, or in the event of his death, it would go to his wife Sally."

Former Principal Chief J.B. Milam, the first chief to be appointed by a U.S. president, funded an expedition in 1938 to search for his gravesite. A gravesite was found in Coahuila, Mexico, but it could not be determined to be the burial place of Sequoyah.

In an article published Oct. 2, 1952, in the Tahlequah Star-Citizen, former Oklahoma Gov. Johnston Murray announced that the "tomb of Sequoyah, the greatest of all American Indians, had been found by Mr. and Mrs. Omer L. Morgan, in Mexico, and that the remains may soon be returned to Oklahoma for re-burial." The article never included where the couple claims to have found the remains, aside from it being a Cherokee settlement in Mexico, but it went on to discuss where Sequoyah's bones would be returned to, including that Mr. Morgan and other Cherokees felt the proper place would be the courthouse square in Tahlequah.

According to The Oklahoman, in 2001, a man by the name of Charles Rogers of Brownsville, Texas, believed he had discovered the site inside a cave near the former village of Sara Rosa in northern Mexico. According to the article, he had no proof and past searches had been fruitless.

While many explorers have tried to find Sequoyah's resting place, it doesn't appear that any ever have - at least not officially. It is likely any of the belongings he would have had on his person would have decayed by now, leaving only bones. And while "the greatest of all Cherokee mysteries" may never truly be solved, the work he left behind forged the way for years of growth among the Cherokee Nation tribe.

What many consider to be his largest contribution to the Cherokee tribe, the creation of the Cherokee syllabary, was actually considered to be witchcraft before it was accepted.

"He and his daughter were put on trial for witchcraft," said Moser. "You have these talking leaves, something that the Cherokee people are not accustomed to seeing."

After Cherokees became convinced that it was indeed not witchcraft, the literacy rate among Cherokees exploded within a short amount of time, said Moser.

Sequoyah fought for the United States in the War of 1812, alongside John Ross, Andrew Jackson, and Sam Houston in the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. A war hero, he was honorably discharged and then later became a diplomat. Sequoyah moved west before the Trail of Tears, during the same period as the Old Settlers. After the Trail of Tears, when there was two factions of Cherokees residing in Indian Territory, he helped broker peace and unification between the two.

"So there was a little bit of unrest there, as you had these two opposing groups," said Moser. "He was one of the people who signed what is called the Act of Union in 1839, which unified the Cherokee Nation - the eastern Cherokees and the western Cherokees - under one name."

No comments:

Post a Comment