How Africa Can Save the World From

a Never-Ending Pandemic

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- As the rest of the world prepares for a vaccine-driven return to normal over the next few months, at her community health center in a poor, working class neighborhood of Cape Town, Andrea Mendelsohn is dreading the arrival of April and May—that’s when the weather will get cooler in the southern hemisphere and bring a surge in coronavirus cases.

Few people in South Africa—aside from medical staff like Mendelsohn—will be vaccinated by then. Elsewhere on the continent even health workers won’t be inoculated, making Africa a large reservoir of the virus that has infected almost 117 million people across the globe and killed more than 2.5 million.

“The arrival of vaccines is going to have zero impact on the third wave but at least I can be confident that when I go to work I won’t die,” Mendelsohn, a senior medical officer in the Western Cape Province’s Department of Health, said in an interview. “I am sure health workers in Malawi and Tanzania want to have the same relief.”

Most countries in Africa have yet to start inoculating their citizens. While developed countries have rushed to vaccinate their populations against Covid-19, fewer than half a million people have received shots in Sub-Saharan Africa, a region of 1.1 billion people. In contrast, the U.S., with a population of about 330 million, has administered over 90 million vaccine doses, while more than a third of the U.K.’s 67 million people have gotten at least one shot.

But anyone in the developed world who thinks they are unaffected by large swaths of un-vaccinated people in Africa, needs to think again, says Phionah Atuhebwe, the New Vaccines Introduction Medical Officer on the continent for the World Health Organization. As long as the pandemic continues to rage among un-vaccinated populations, spawning new, more virulent, vaccine-resistant strains, no one is safe, she said.

“The virus will definitely mutate and will keep mutating; the longer we keep the virus around the more mutations we’ll see,” Atuhebwe said in an interview from Brazzaville, in the Republic of Congo. “If Africa is not vaccinated and we are a source of mutations, we put the whole world at risk.”

Already the vaccine developed by AstraZeneca Plc and the University of Oxford has proved largely ineffective in preventing mild disease from infections with a strain of the virus first identified in South Africa. That mutation has spread to at least 48 countries, including the U.K. and the U.S.

Rich nations pre-paid for their vaccines and also got organized quicker and earlier, leaving countries in Africa scrambling for scraps. The affluent world’s vaccine grab was characterized in January by WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus as a “catastrophic moral failure.” Just 10 countries administered 75% of all vaccinations, United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said in February, calling it “wildly uneven and unfair.”

A report by anti-poverty group One said last month that the world’s richest countries are on track to accumulate over 1 billion more doses than they need to fully vaccinate their populations, adding that the excess shots alone would be sufficient to inoculate the entire adult population of Africa.

“It’ll be a fatal mistake if the developed world sees this as a case where we’ll vaccinate our people and then people in other parts of the world take care of their own business,” said John Nkengasong, director of the Africa Center for Disease Control and Prevention. “Covid won’t be defeated until it’s defeated everywhere.”

The mad dash to corner vaccines shows rich countries have learned little from the global swine flu pandemic in 2009, when poor nations were left high and dry, says Helen Rees, chairwoman of the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority. Despite the heightened risk of the virus spreading with increased interconnectedness, “there was not a thought about what would happen to the rest of the world,” she said.

Countries from Nigeria to Ethiopia and Zimbabwe have large numbers of their citizens living and working in Europe, North America and even Asia, and regular flights mean that just as easily as the virus arrived in Africa from Europe, mutated strains could be spread into the developed world by returning travelers.

In addition, a slow vaccine rollout could further delay the economic recovery in Africa, which contracted for the first time in 25 years last year. Already, Zambia has defaulted on its debt and Ethiopia and Chad are seeking debt relief. The developed world relies on the continent’s natural resources for much of the raw materials it needs. West Africa accounts for 60% of the world's cocoa supply, the Democratic Republic of Congo is the key source of cobalt needed for electric vehicles and tantalum used in mobile phones. South Africa is the world's biggest source of platinum.

Vaccines are slowly trickling into Africa. The African Union has secured some supplies, China has provided vaccines to Zimbabwe and other African nations and countries such as Israel are beginning to donate excess supplies. Still, most African countries are almost entirely reliant on Covax—the initiative backed by the WHO, the vaccine alliance Gavi and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations that offers vaccines cheaply to developing countries. Covax began distributing vaccines to countries such as Ghana and the Ivory Coast last month.

But the program will only cover 20% of the populations of its members by year-end. Of the 304 million doses administered worldwide so far, fewer than 0.2% have been in Sub-Saharan Africa, home to 14% of the world’s population.

Richer nations are beginning to acknowledge that poorer countries need better access to vaccines. In an interview with the Financial Times in February, French President Emmanuel Macron called the vaccine gap “an unprecedented acceleration of global inequality.” At their meeting last month, leaders of the G7 countries pledged $7.5 billion to Covax and also called on countries to donate surplus supplies.

Granted, African governments haven’t helped themselves. Few made attempts to secure supplies directly from pharmaceutical companies, with South Africa—which has a wealth of medical expertise and is the site of five coronavirus vaccine trials—only signing deals this year.

“The bulk of the blame should be placed on African leaders for being somewhat nonchalant and non-proactive,” said Ifeoluwapu Asekun-Olarinmoye, an epidemiologist at Nigeria’s Babcock University.

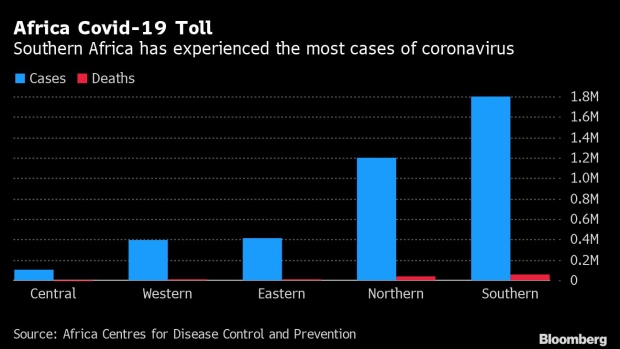

That’s in part because the official Covid-related death toll across Africa is just under 106,000 with almost 4 million cases reported, small compared to the rest of the world. But testing has been sparse and many infections and deaths have gone unrecorded. At times over the last few months hospitals from Cape Town to Harare and Lagos have groaned under the strain. Doctors and oxygen have been in short supply and people have taken to social media to search for beds for their afflicted relatives.

With vaccines beginning to arrive, other challenges are coming to the fore. The continent is plagued by poor health infrastructure, a shortage of trained personnel and inadequate data on the people who need to be vaccinated.

Take Nigeria, for instance. Africa’s most populous nation has about 214 million people, most living in areas that are hard to reach. Fewer than a third of the country’s 195,000 kilometer (121,170-mile) road network is paved; power supply—even in the biggest cities—is unreliable, making it a challenge to keep vaccines refrigerated; and a 15-year gap since the last census means the government has little idea about the whereabouts of vulnerable groups like the elderly. The same applies to many African countries.

“We don’t know where they live, we don’t know how many there are, we don’t know how to find them,” Atuhebwe said in a webinar.

In countries like Tanzania virus denial is holding back attempts to immunize the population. President John Magufuli has declared his country Covid-free even as people continue to die from it. Vaccine skepticism runs high in some countries, with 15 high school students taken to hospital in south-west Cameroon last month after leaping from the second floor to escape what they thought was a team of medics arriving to vaccinate them.

Meanwhile, some shots—like Russia’s Sputnik V and vaccines from China’s CanSino Biologics Inc.—have sparked concern. They use a cold germ to carry the genetic material of the Covid virus into patients’ cells to trigger an immune response. A trial in South Africa of an HIV vaccine using the same vector more than a decade ago was tied to an increase in HIV infections. South Africa has the world’s biggest AIDS epidemic and many of its neighbors have similar infection rates.

Even when vaccines are suitable, some African countries can’t afford shots outside the Covax system. Since African countries didn’t contribute to the development of the shots and didn’t pre-order, they don’t get the discounts offered to richer countries. In January, Anban Pillay, a deputy director general in South Africa’s Department of Health, said the country would pay $5.25 per dose of AstraZeneca’s shot compared with about $3 the European Union was paying.

All that has meant a very slow pace of vaccination. South Africa, the continent’s most developed country, is inoculating at most about 11,000 people a day with the single-dose Johnson & Johnson shot, a pace that would take a decade to cover the 40 million people the government wants to vaccinate. Most vaccines available to African nations require two shots. If a double-dose regime is followed and 780 million Africans inoculated over 12 months to attain herd immunity, there would need to be 7 million vaccinations a day, according to Ernest Darkoh, founder of Cape Town-based Broadreach Group, which works with governments on healthcare.

That’s unlikely to happen without a lot of help.

“The whole world needs to walk this journey together,” said Mmboneni Muofhe, a deputy director general at South Africa’s Department of Science and Technology. “We are going to find ourselves sitting with a variant that defies all the vaccines. We are sitting on a ticking time bomb.”

— With Ruth Olurounbi, Katarina Hoije, Pius Lukong, and Zoe Schneeweiss

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.

No comments:

Post a Comment