Alexandra Mae Jones

CTVNews.ca writer

@AlexandraMaeJ Contact

Hydrofractures occur when the pressure of liquid water on top of ice causes it to split due to the water being denser.

Amery Ice Shield is the third-largest ice shelf branching off from Antarctica on the east side of the continent, and at 1,400 metres thick, it is rare to see a hydrofracture crack it open completely.

Researchers described the process of tracking this event in a paper published last week in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

The lake itself was unnamed, and had resided inside the shelf, covered by a cap of ice. When the shelf cracked open under the lake and the water drained out, it left behind a wide depression in the ice shelf.

This is an ice “doline” — a term that means a naturally enclosed depression in the ground, usually referring to sinkholes.

The ice doline was around 11 square kilometres, and was peppered with some of the cracked remnants of the ice lid that once sat on top of the lake.

It was a small lake in terms of length, but still around half the size of Lake Minnewanka in Alberta, or 12 times the size of Lake Louise.

And it was deep, containing around 600-750 million cubic metres of water, around twice the volume of San Diego Bay, according to another release from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. This far exceeds the amount of meltwater that the shelf normally sees.

How did researchers figure out the amount of water? The loss of a lake that size made a marked difference in the elevation of the ice shelf itself, something that can be seen from space if you look close enough.

Researchers used a laser instrument on NASA’s ICESat-2 in order to calculate the exact change in elevation caused by the drainage of the lake.

“ICESat-2 orbits with exactly repeating ground tracks and comparing elevations before and after the lake drained showed us the dramatic vertical scale of the disruption,” Helen Fricker, a professor at Scripps Institution of Oceanography and coauthor of the study, said in the first news release.

After the lake drained, that region of the ice shelf tipped up, with the surface of the shelf rising by “as much as 36 metres around the lake,” Warner said.

“The loss of lake water locally reduced the weight on the floating ice shelf so that ocean pressure lifted it upwards at the doline.”

The lake itself sunk deeper into the shelf, with the basin of the cavity found 80 metres below the original lake surface.

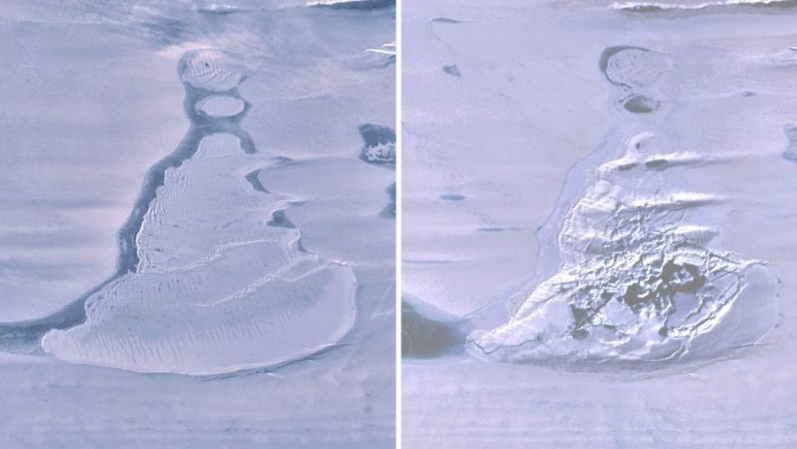

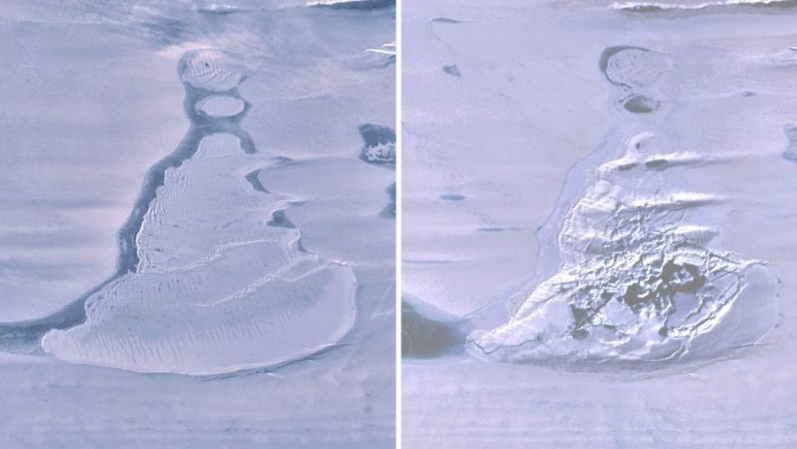

Photos of the lake from a satellite showing the before-and-after process show how the movement of the ice shelf also created a new, smaller pool of water on what used to be an arm of water moving away from the lake, with the original lake surface appearing visibly cracked and drained.

It’s possible that the doline could fill up with water once again, or that the hydrofracture could reopen and drain that water again, Warner said.

Although this phenomenon isn’t thought to be necessarily directly connected to climate change, the movement of ice sheets on the edge of regions such as Antarctica are critical to track. The loss of an ice sheet, or the fracturing of an ice sheet away from the continent, could speed up the loss of ice on the land mass itself, which would contribute to a rise in sea levels if it melted.

@AlexandraMaeJ Contact

Published Wednesday, June 30, 2021

Landsat 8 images over the Southern Amery Ice Shelf on the east coast of Antarctica show the ice-covered lake before drainage and the resulting ice doline with summer meltwater (Landsat 8/ UC San Diego, Scripps Institution of Oceanography)

TORONTO -- In 2019, a lake on an ice sheet in East Antarctica vanished completely over the course of three days.

The strange occurrence went unnoticed until the next summer, when Dr. Roland Warner, a glaciologist with the Australian Antarctic Program Partnership at the University of Tasmania, noticed discrepancies in satellite images of the Amery Ice Shelf.

As he investigated further, he and other researchers concluded that something rare had happened: a hydrofracture.

Read the release: Scientists detect sudden loss of large Antarctic lake

“We believe a large crack opened briefly in the floating ice shelf and drained the entire lake into the ocean within three days,” Warner said in a news release.

“The lake held more water than Sydney Harbour and the flow into the ocean beneath would have been like the flow over Niagara Falls, so it would have been an impressive sight.”

Landsat 8 images over the Southern Amery Ice Shelf on the east coast of Antarctica show the ice-covered lake before drainage and the resulting ice doline with summer meltwater (Landsat 8/ UC San Diego, Scripps Institution of Oceanography)

TORONTO -- In 2019, a lake on an ice sheet in East Antarctica vanished completely over the course of three days.

The strange occurrence went unnoticed until the next summer, when Dr. Roland Warner, a glaciologist with the Australian Antarctic Program Partnership at the University of Tasmania, noticed discrepancies in satellite images of the Amery Ice Shelf.

As he investigated further, he and other researchers concluded that something rare had happened: a hydrofracture.

Read the release: Scientists detect sudden loss of large Antarctic lake

“We believe a large crack opened briefly in the floating ice shelf and drained the entire lake into the ocean within three days,” Warner said in a news release.

“The lake held more water than Sydney Harbour and the flow into the ocean beneath would have been like the flow over Niagara Falls, so it would have been an impressive sight.”

Hydrofractures occur when the pressure of liquid water on top of ice causes it to split due to the water being denser.

Amery Ice Shield is the third-largest ice shelf branching off from Antarctica on the east side of the continent, and at 1,400 metres thick, it is rare to see a hydrofracture crack it open completely.

Researchers described the process of tracking this event in a paper published last week in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

The lake itself was unnamed, and had resided inside the shelf, covered by a cap of ice. When the shelf cracked open under the lake and the water drained out, it left behind a wide depression in the ice shelf.

This is an ice “doline” — a term that means a naturally enclosed depression in the ground, usually referring to sinkholes.

The ice doline was around 11 square kilometres, and was peppered with some of the cracked remnants of the ice lid that once sat on top of the lake.

It was a small lake in terms of length, but still around half the size of Lake Minnewanka in Alberta, or 12 times the size of Lake Louise.

And it was deep, containing around 600-750 million cubic metres of water, around twice the volume of San Diego Bay, according to another release from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. This far exceeds the amount of meltwater that the shelf normally sees.

How did researchers figure out the amount of water? The loss of a lake that size made a marked difference in the elevation of the ice shelf itself, something that can be seen from space if you look close enough.

Researchers used a laser instrument on NASA’s ICESat-2 in order to calculate the exact change in elevation caused by the drainage of the lake.

“ICESat-2 orbits with exactly repeating ground tracks and comparing elevations before and after the lake drained showed us the dramatic vertical scale of the disruption,” Helen Fricker, a professor at Scripps Institution of Oceanography and coauthor of the study, said in the first news release.

After the lake drained, that region of the ice shelf tipped up, with the surface of the shelf rising by “as much as 36 metres around the lake,” Warner said.

“The loss of lake water locally reduced the weight on the floating ice shelf so that ocean pressure lifted it upwards at the doline.”

The lake itself sunk deeper into the shelf, with the basin of the cavity found 80 metres below the original lake surface.

Photos of the lake from a satellite showing the before-and-after process show how the movement of the ice shelf also created a new, smaller pool of water on what used to be an arm of water moving away from the lake, with the original lake surface appearing visibly cracked and drained.

It’s possible that the doline could fill up with water once again, or that the hydrofracture could reopen and drain that water again, Warner said.

Although this phenomenon isn’t thought to be necessarily directly connected to climate change, the movement of ice sheets on the edge of regions such as Antarctica are critical to track. The loss of an ice sheet, or the fracturing of an ice sheet away from the continent, could speed up the loss of ice on the land mass itself, which would contribute to a rise in sea levels if it melted.

No comments:

Post a Comment