Britain after a nuclear attack: the BBC film that shocked a generation

Inspired by the leaked Protect and Survive films, in 1984 a BBC team set out to create a relentlessly accurate vision of an atomic bomb landing on Sheffield. Here’s how they did it.

By NS Podcasts, May Robson and Jude Rogers

Threads, 1984. Photo by AJ Pics / Alamy Stock Photo

HARROWING

BritBox pulls Nuclear disaster film Threads ahead of the Ukraine war after it gave viewers nightmares

Mary Gallagher, 3 Mar 2022

BRITBOX pulled nuclear disaster film Threads from its platform ahead of the Ukraine war after it gave viewers nightmares.

The apocalyptic drama left people so terrified it was rarely repeated on the BBC after it first aired in 1984.

3The eighties BBC film has been off air for more than a decade and has now been pulled from BritBox over its distressing portrayal of nuclear war in BritainCredit: BBC

3Threads gave people nightmares when it first aired and clips of it are now doing the rounds on social mediaCredit: BBC

It did however land on BritBox, until earlier this year, and clips of the film also emerged on TikTok, with people saying that they “can’t believe” it was ever broadcast on the telly.

One distressing scene was captioned on TikTok: “Who as a kid had nightmares after watching this?”

And one comment from a user read: “To think they showed this in schools in the Eighties. No wonder 80s kids were hard as nails!”

Threads was about a nuclear attack in Sheffield.

Set in the near future, Threads examined a thirteen year period in the projected life - and death - of the city of Sheffield, during which time Britain is devastated by nuclear attacks.

When it first aired on BBC Two it was "the night Britain didn't sleep", so shocked were the people that had tuned in.

It aired once again the following year and didn't make it back on screen until 18 years later.

It was also released on DVD and aired once more on telly in April 2005.

BritBox pulls Nuclear disaster film Threads ahead of the Ukraine war after it gave viewers nightmares

Mary Gallagher, 3 Mar 2022

BRITBOX pulled nuclear disaster film Threads from its platform ahead of the Ukraine war after it gave viewers nightmares.

The apocalyptic drama left people so terrified it was rarely repeated on the BBC after it first aired in 1984.

3The eighties BBC film has been off air for more than a decade and has now been pulled from BritBox over its distressing portrayal of nuclear war in BritainCredit: BBC

3Threads gave people nightmares when it first aired and clips of it are now doing the rounds on social mediaCredit: BBC

It did however land on BritBox, until earlier this year, and clips of the film also emerged on TikTok, with people saying that they “can’t believe” it was ever broadcast on the telly.

One distressing scene was captioned on TikTok: “Who as a kid had nightmares after watching this?”

And one comment from a user read: “To think they showed this in schools in the Eighties. No wonder 80s kids were hard as nails!”

Threads was about a nuclear attack in Sheffield.

Set in the near future, Threads examined a thirteen year period in the projected life - and death - of the city of Sheffield, during which time Britain is devastated by nuclear attacks.

When it first aired on BBC Two it was "the night Britain didn't sleep", so shocked were the people that had tuned in.

It aired once again the following year and didn't make it back on screen until 18 years later.

It was also released on DVD and aired once more on telly in April 2005.

How One Apocalyptic BBC Movie Scarred a Generation of U.K. Schoolchildren

Rae Alexandra

Sep 26, 2019

This article is more than 3 years old.

The cover of 2018's remastered blu-ray set of 'Threads.' (BBC)

Thirty-five years ago this week, the BBC aired Threads, one of the most searing movies about nuclear war in TV history. The following year, the docu-drama aired on TBS and became, at the time, the most watched basic cable show in America. Today it can be found on dedicated horror streaming channel, Shudder. But back in 1984? It was recorded by teachers across the U.K. and shown to an entire generation of schoolchildren.

While it's understandable that a film in which two-thirds of Britain is destroyed by nuclear bombs would be deemed school-worthy—especially during the Cold War—the imagery in Threads was extraordinarily visceral. At the moment of the country's destruction, for example, the film shows bodies burning (including a baby), rubble landing on people's heads, humans crawling through fire, buildings falling, charred hands, a cat dying, an elderly woman soiling herself and a man violently vomiting.

Lest any viewers miss the point of the horrors unfolding, there is a sporadic, authoritative BBC voiceover to move things along. "An explosion... has sucked up this debris and made it radioactive," it says in the bomb's immediate aftermath. "The wind has blown it here. This level of attack has broken most of the windows in Britain. Many roofs are open to the sky; some where the lethal dust gets in. In these early stages, the symptoms of radiation sickness and the symptoms of panic are identical."

Following that is a full hour of slow, harrowing deaths, interspersed with civilians being teargassed for wanting supplies, finally culminating in post-apocalyptic nuclear winter, the spread of disease, and a heavy veil of abject, filthy hopelessness. The film ends with a teenage girl having a stillbirth after being raped.

Mad Max and The Road ain't got nothin' on the second hour of this thing.

Rae Alexandra

Sep 26, 2019

This article is more than 3 years old.

The cover of 2018's remastered blu-ray set of 'Threads.' (BBC)

Thirty-five years ago this week, the BBC aired Threads, one of the most searing movies about nuclear war in TV history. The following year, the docu-drama aired on TBS and became, at the time, the most watched basic cable show in America. Today it can be found on dedicated horror streaming channel, Shudder. But back in 1984? It was recorded by teachers across the U.K. and shown to an entire generation of schoolchildren.

Threads starts by juxtaposing the mundane everyday activities of two normal English families with calamitous events playing out on the world stage. The film uses a worst case scenario (Soviet Union invades Iran, America retaliates, England gets caught in the crossfire) alongside the bleakest of visuals, to emphasize just how little power the average person has over their own fate. Both protest and prayer are depicted as utterly useless.

While it's understandable that a film in which two-thirds of Britain is destroyed by nuclear bombs would be deemed school-worthy—especially during the Cold War—the imagery in Threads was extraordinarily visceral. At the moment of the country's destruction, for example, the film shows bodies burning (including a baby), rubble landing on people's heads, humans crawling through fire, buildings falling, charred hands, a cat dying, an elderly woman soiling herself and a man violently vomiting.

Lest any viewers miss the point of the horrors unfolding, there is a sporadic, authoritative BBC voiceover to move things along. "An explosion... has sucked up this debris and made it radioactive," it says in the bomb's immediate aftermath. "The wind has blown it here. This level of attack has broken most of the windows in Britain. Many roofs are open to the sky; some where the lethal dust gets in. In these early stages, the symptoms of radiation sickness and the symptoms of panic are identical."

Following that is a full hour of slow, harrowing deaths, interspersed with civilians being teargassed for wanting supplies, finally culminating in post-apocalyptic nuclear winter, the spread of disease, and a heavy veil of abject, filthy hopelessness. The film ends with a teenage girl having a stillbirth after being raped.

Mad Max and The Road ain't got nothin' on the second hour of this thing.

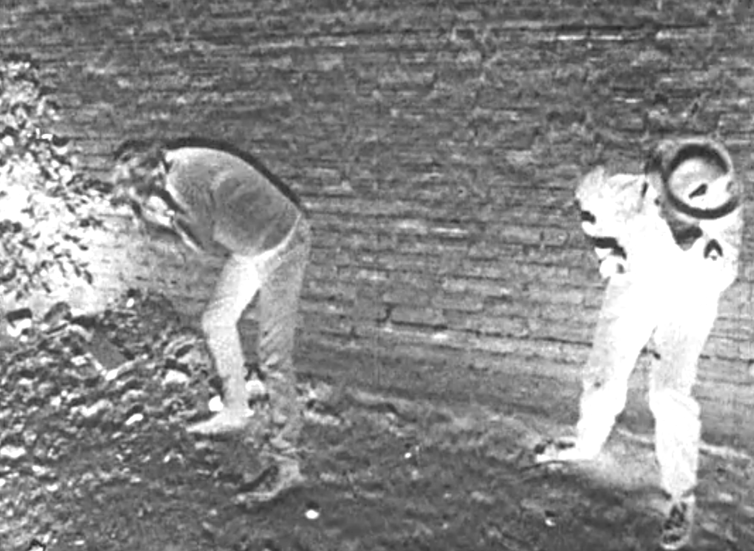

Unlucky survivors of the nuclear bomb in 'Threads.' (BBC)

That Threads was deemed appropriate viewing for young schoolchildren is unfathomable for a lot of the adults who were forced to watch it the first time around. "I was 13 and I believe the school showed it to us in a Religious Studies lesson," British father-of-two, Chris West says. "I remember the immediate fear of how real it all looked. Most of the stuff I had seen up until then had been a steady diet of Star Wars and Superman, so the gritty British camerawork and acting had a real impact. From that night on, I had night terrors—the most hideous and real nightmares—for years. Sirens I heard in even the daytime would make me stop dead in my tracks."

Like West, Will Jones, 44, had recurring nightmares for a decade after being shown Threads in English class 30 years ago. "It was terrifying because it was so believable," he says. "I remember talking about it extensively with friends and hoping it would never happen, but believing it would. I’m not sure it’s fair for teenagers to have this dumped on them."

Threads was not the first time children were subjected to adult horrors in the course of their school day. In the '50s and '60s, there were atomic duck and cover videos and drills.

Today, of course, children of all ages in almost all American public schools suffer through active shooter drills on a regular basis—and it's not without consequence. According to the New York Times, "Psychologists and many educators say frequent, realistic drills contribute to anxiety and depression in children," and that "nearly 60 percent of American teenagers said they were very or somewhat worried about a mass shooting at school."

Where Threads distinguished itself though, is in the fact that it offered no instruction or advice whatsoever. In fact, the film quite emphatically told viewers there was absolutely nothing they could do to stay safe in the event of a nuclear explosion. The best they could hope for was instant death.

Threads was not specifically made for a young audience, nor was it the BBC's intention for it turn into an educational video for school-aged children. Still, it remains an example of how kids can get caught up in the proverbial crossfire when adults aren't doing the right thing—something this month's climate change protesters can surely relate to.

Fortunately for those who saw Threads in the '80s, the end of the Cold War, plus time, has enabled some of those once-terrified children to develop a sense of humor about it all. And, in 1984, this surely felt impossible...

That Threads was deemed appropriate viewing for young schoolchildren is unfathomable for a lot of the adults who were forced to watch it the first time around. "I was 13 and I believe the school showed it to us in a Religious Studies lesson," British father-of-two, Chris West says. "I remember the immediate fear of how real it all looked. Most of the stuff I had seen up until then had been a steady diet of Star Wars and Superman, so the gritty British camerawork and acting had a real impact. From that night on, I had night terrors—the most hideous and real nightmares—for years. Sirens I heard in even the daytime would make me stop dead in my tracks."

Like West, Will Jones, 44, had recurring nightmares for a decade after being shown Threads in English class 30 years ago. "It was terrifying because it was so believable," he says. "I remember talking about it extensively with friends and hoping it would never happen, but believing it would. I’m not sure it’s fair for teenagers to have this dumped on them."

Threads was not the first time children were subjected to adult horrors in the course of their school day. In the '50s and '60s, there were atomic duck and cover videos and drills.

Today, of course, children of all ages in almost all American public schools suffer through active shooter drills on a regular basis—and it's not without consequence. According to the New York Times, "Psychologists and many educators say frequent, realistic drills contribute to anxiety and depression in children," and that "nearly 60 percent of American teenagers said they were very or somewhat worried about a mass shooting at school."

Where Threads distinguished itself though, is in the fact that it offered no instruction or advice whatsoever. In fact, the film quite emphatically told viewers there was absolutely nothing they could do to stay safe in the event of a nuclear explosion. The best they could hope for was instant death.

Threads was not specifically made for a young audience, nor was it the BBC's intention for it turn into an educational video for school-aged children. Still, it remains an example of how kids can get caught up in the proverbial crossfire when adults aren't doing the right thing—something this month's climate change protesters can surely relate to.

Fortunately for those who saw Threads in the '80s, the end of the Cold War, plus time, has enabled some of those once-terrified children to develop a sense of humor about it all. And, in 1984, this surely felt impossible...

BEFORE THREADS ON BW TV

The War Game: how I showed that BBC bowed to government over nuclear attack film

Published: June 2, 2015

The revolving door

Why did the BBC permit its cherished independence to be compromised in this way? The reasons take us to the heart of the relations between British broadcasting and the state during the Cold War era. The chair of the BBC board of governors, Lord Normanbrook, who had first written to Trend to alert Whitehall to the film, was himself a former cabinet secretary who had actually helped draw up the very civil-defence plans in case of nuclear war which Watkins’ film was now exposing as inadequate.

He was part of a revolving door between Whitehall and the BBC at this time. There was a “Home Office liaison official” working at the heart of the BBC as a “partner” in civil defence. One has to remember this was only 20 years after the end of World War II and just three after the Cuban missile crisis, which had brought the world to the brink of nuclear conflict

A history of intervention

The affair recalls other crises with government in the BBC’s history, such as the Real Lives: At The Edge of The Union documentary from 1985, which profiled Ulster Unionist and Sinn Féin politicians. Then home secretary Leon Brittan threatened to veto it if the BBC went ahead with transmission.

More recent was the Hutton Inquiry of 2003-04. It led to the resignations of both BBC director-general Greg Dyke and chair of the BBC board of governors Gavyn Davies, following Lord Hutton’s criticisms of the BBC over its reporting of the alleged “sexing up” of the British government’s dossier on supposed weapons of mass destruction in Iraq.

The difference between these later controversies and The War Game is that both At The Edge of The Union and Huttongate were examples of conflict between government and the broadcaster. In the case of The War Game, the censorship was entirely consensual at the most senior levels of the corporation.

As Whitehall officials noted with typical civil-service nuance in their memo concerning Greene’s meeting with Bowden, if the BBC and government were to disagree over whether the film should be shown, that would be a matter in which government ministers might have to intervene. But “there is no need to consider this possibility, with its serious political implications, at the moment”. Not with such a pliant leadership team at the BBC.

Published: June 2, 2015

The War Game depicted true horror of nuclear war.

On the front of a folder of declassified 1965 Cabinet Office papers from the national archives, scribbled in pencil by an unknown hand, is a legend that reads: “HMG censorship of BBC film The War Game”. It is enough to make anyone familiar with the troubled history of this film draw a sharp intake of breath.

Fifty years ago Peter Watkins, a brilliant 29-year-old director at the BBC, made The War Game, a powerful dramatised documentary that portrayed what might happen if Britain were subject to a nuclear strike. Depicting harrowing scenes of firestorms, radiation sickness and the complete breakdown of civil defence and law and order, the film was banned from screening by the BBC.

Despite having commissioned it, the corporation claimed The War Game was “too horrific for the medium of broadcasting”. It stressed it had reached this decision on its own and without “outside pressure of any kind”. But when it emerged that prior to announcing its ban, the BBC had invited officials from Whitehall to preview the film, it became a major cause célèbre.

Watkins resigned from the BBC in protest, claiming its much-vaunted charter of independence from government had been violated. The furore helped The War Game become one of the iconic films of the 1960s, especially when after a limited cinema release in 1966, it went on to win an Oscar for Best Documentary Feature. It was not shown on television until 1985.

On the front of a folder of declassified 1965 Cabinet Office papers from the national archives, scribbled in pencil by an unknown hand, is a legend that reads: “HMG censorship of BBC film The War Game”. It is enough to make anyone familiar with the troubled history of this film draw a sharp intake of breath.

Fifty years ago Peter Watkins, a brilliant 29-year-old director at the BBC, made The War Game, a powerful dramatised documentary that portrayed what might happen if Britain were subject to a nuclear strike. Depicting harrowing scenes of firestorms, radiation sickness and the complete breakdown of civil defence and law and order, the film was banned from screening by the BBC.

Despite having commissioned it, the corporation claimed The War Game was “too horrific for the medium of broadcasting”. It stressed it had reached this decision on its own and without “outside pressure of any kind”. But when it emerged that prior to announcing its ban, the BBC had invited officials from Whitehall to preview the film, it became a major cause célèbre.

Watkins resigned from the BBC in protest, claiming its much-vaunted charter of independence from government had been violated. The furore helped The War Game become one of the iconic films of the 1960s, especially when after a limited cinema release in 1966, it went on to win an Oscar for Best Documentary Feature. It was not shown on television until 1985.

Spin by any other name

The question of who banned The War Game – the government or the BBC – has raged for years. It has been the subject of claim and counter-claim not least by Watkins himself, now retired in France. But the trail within BBC archives goes cold as to who exactly banned it, which has meant that there has always been a tantalising lack of hard evidence.

That changed when I gained access to the previously classified Cabinet Office papers. They appear to show the role of Whitehall in the film’s original TV banning was much more extensive than anything publicly acknowledged by either the government or the BBC at the time.

Examining the files, I was surprised at the level of scrutiny the government paid to the film and how explicit discussions were to suppress it. Politicians, not just civil servants, were involved, including then prime minister Harold Wilson. None of the discussions concerned preserving the independence of the corporation, but rather how to find a way to suppress the film without implicating the government or embarrassing the BBC. Much as we think we live in the era of political spin, the emphasis in the discussions was less on whether to censor but how best to present that censorship to the public.

Sir Burke Trend, Wilson’s cabinet secretary, was explicit in an internal briefing document of October 6 1965, following his invitation by the BBC to see the film in the late September:

The difficulty for the BBC, no less than for the government is to think of some reason for suppressing the film which would not stir up controversy or provoke suspicion that it was motivated by political prejudice.

The question of who banned The War Game – the government or the BBC – has raged for years. It has been the subject of claim and counter-claim not least by Watkins himself, now retired in France. But the trail within BBC archives goes cold as to who exactly banned it, which has meant that there has always been a tantalising lack of hard evidence.

That changed when I gained access to the previously classified Cabinet Office papers. They appear to show the role of Whitehall in the film’s original TV banning was much more extensive than anything publicly acknowledged by either the government or the BBC at the time.

Examining the files, I was surprised at the level of scrutiny the government paid to the film and how explicit discussions were to suppress it. Politicians, not just civil servants, were involved, including then prime minister Harold Wilson. None of the discussions concerned preserving the independence of the corporation, but rather how to find a way to suppress the film without implicating the government or embarrassing the BBC. Much as we think we live in the era of political spin, the emphasis in the discussions was less on whether to censor but how best to present that censorship to the public.

Sir Burke Trend, Wilson’s cabinet secretary, was explicit in an internal briefing document of October 6 1965, following his invitation by the BBC to see the film in the late September:

The difficulty for the BBC, no less than for the government is to think of some reason for suppressing the film which would not stir up controversy or provoke suspicion that it was motivated by political prejudice.

The revolving door

Why did the BBC permit its cherished independence to be compromised in this way? The reasons take us to the heart of the relations between British broadcasting and the state during the Cold War era. The chair of the BBC board of governors, Lord Normanbrook, who had first written to Trend to alert Whitehall to the film, was himself a former cabinet secretary who had actually helped draw up the very civil-defence plans in case of nuclear war which Watkins’ film was now exposing as inadequate.

He was part of a revolving door between Whitehall and the BBC at this time. There was a “Home Office liaison official” working at the heart of the BBC as a “partner” in civil defence. One has to remember this was only 20 years after the end of World War II and just three after the Cuban missile crisis, which had brought the world to the brink of nuclear conflict

.

Key memo p.1, September 1965. Cabinet Office

The BBC’s director-general at this time, ostensibly its independent editor-in-chief, was Sir Hugh Carleton Greene. Greene is now commonly remembered as a great liberalising figure who opened the BBC up, shedding its establishment image with challenging programmes like That Was The Week That Was (1962-63) and The Wednesday Play (1964-70)

Key memo p.1, September 1965. Cabinet Office

The BBC’s director-general at this time, ostensibly its independent editor-in-chief, was Sir Hugh Carleton Greene. Greene is now commonly remembered as a great liberalising figure who opened the BBC up, shedding its establishment image with challenging programmes like That Was The Week That Was (1962-63) and The Wednesday Play (1964-70)

.

Same memo, p.2. Cabinet Office

But Greene was also a scion of the Cold War. Prior to becoming director-general, he had led psychological warfare against anti-communist guerrillas in Malaya and organised the BBC’s East European Service broadcasts to behind the Iron Curtain.

For senior BBC officials, the key issue with Peter Watkins’ carefully researched film was whether its graphic depiction of national collapse in the aftermath of thermonuclear attack would undermine public morale during the Cold War and give possible succour to the Soviets. This seems to be why Greene and Normanbrook were keen to refer the matter to government for a final decision.

Indeed the Cabinet Office papers reveal that Greene, in an early meeting with the leader of the House of Commons, Herbert Bowden, had even suggested that if the government decided not to show the film, he himself would be prepared to put out a press release to the effect that the BBC had taken the decision alone. This was exactly what did occur in November 1965.

Same memo, p.2. Cabinet Office

But Greene was also a scion of the Cold War. Prior to becoming director-general, he had led psychological warfare against anti-communist guerrillas in Malaya and organised the BBC’s East European Service broadcasts to behind the Iron Curtain.

For senior BBC officials, the key issue with Peter Watkins’ carefully researched film was whether its graphic depiction of national collapse in the aftermath of thermonuclear attack would undermine public morale during the Cold War and give possible succour to the Soviets. This seems to be why Greene and Normanbrook were keen to refer the matter to government for a final decision.

Indeed the Cabinet Office papers reveal that Greene, in an early meeting with the leader of the House of Commons, Herbert Bowden, had even suggested that if the government decided not to show the film, he himself would be prepared to put out a press release to the effect that the BBC had taken the decision alone. This was exactly what did occur in November 1965.

A history of intervention

The affair recalls other crises with government in the BBC’s history, such as the Real Lives: At The Edge of The Union documentary from 1985, which profiled Ulster Unionist and Sinn Féin politicians. Then home secretary Leon Brittan threatened to veto it if the BBC went ahead with transmission.

More recent was the Hutton Inquiry of 2003-04. It led to the resignations of both BBC director-general Greg Dyke and chair of the BBC board of governors Gavyn Davies, following Lord Hutton’s criticisms of the BBC over its reporting of the alleged “sexing up” of the British government’s dossier on supposed weapons of mass destruction in Iraq.

The difference between these later controversies and The War Game is that both At The Edge of The Union and Huttongate were examples of conflict between government and the broadcaster. In the case of The War Game, the censorship was entirely consensual at the most senior levels of the corporation.

As Whitehall officials noted with typical civil-service nuance in their memo concerning Greene’s meeting with Bowden, if the BBC and government were to disagree over whether the film should be shown, that would be a matter in which government ministers might have to intervene. But “there is no need to consider this possibility, with its serious political implications, at the moment”. Not with such a pliant leadership team at the BBC.

Author

John Cook

Professor in Media, Glasgow Caledonian University

Disclosure statement

John Cook has received past funding from AHRC.

Professor in Media, Glasgow Caledonian University

Disclosure statement

John Cook has received past funding from AHRC.

No comments:

Post a Comment