The Treaty Meant to Control Nuclear Risks is Under Strain 80 years after the US Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

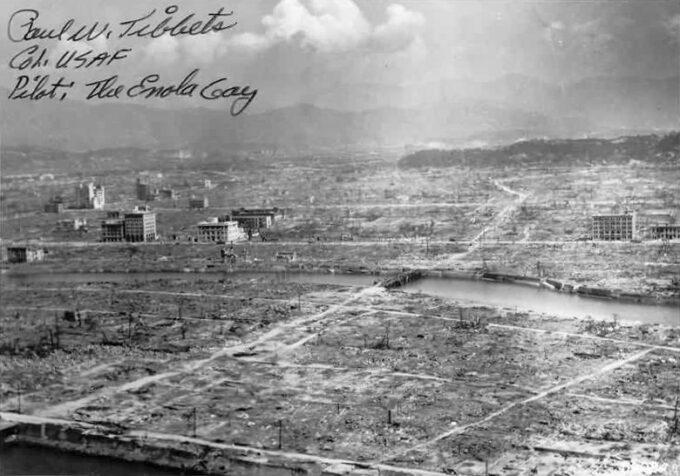

Hiroshima August 1945. Photograph Source: U.S. Navy Public Affairs Resources Website – Public Domain

Eighty years ago – on Aug. 6 and 9, 1945 – the U.S. military dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, thrusting humanity into a terrifying new age. In mere moments, tens of thousands of people perished in deaths whose descriptions often defy comprehension.

The blasts, fires and lingering radiation effects caused such tragedies that even today no one knows exactly how many people died. Estimates place the death toll at up to 140,000 in Hiroshima and over 70,000 in Nagasaki, but the true human costs may never be fully known.

The moral shock of the U.S. attacks reverberated far beyond Japan, searing itself into the conscience of global leaders and the public. It sparked a movement I and others continue to study: the efforts of the international community to ensure that such horrors are never repeated.

Racing toward the brink

The memories of Hiroshima and Nagasaki cast a long shadow over global efforts to contain nuclear arms. The 1968 Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, more commonly known as the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, was a powerful, if imperfect, effort to prevent future nuclear catastrophe. Its creation reflected not just morality, but also the practical fears and self-interests of nations.

As the years passed, views of the bombings as justified acts began to shift. Harrowing firsthand accounts from Hibakusha – the survivors – reached wide audiences. One survivor, Setsuko Thurlow, described the sight of other victims:

“It was like a procession of ghosts. I say ‘ghosts’ because they simply did not look like human beings. Their hair was rising upwards, and they were covered with blood and dirt, and they were burned and blackened and swollen. Their skin and flesh were hanging, and parts of the bodies were missing. Some were carrying their own eyeballs.”

Nuclear dangers increased further with the advent of hydrogen bombs, or thermonuclear weapons, capable of destruction far greater than the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. What had once seemed a decisive end to a global war now looked like the onset of an era wherein no city or civilization would truly be safe.

These shifting perceptions shaped how nations viewed the nuclear age. In the decades following World War II, nuclear technology rapidly spread. By the early 1960s, the United States and the Soviet Union aimed thousands of nuclear warheads at one another.

Meanwhile, there were concerns that countries in East Asia, Europe and the Middle East would acquire the bomb. U.S. President John F. Kennedy even warned that “15 or 20 or 25 nations” might be able to develop nuclear weapons during the 1970s, resulting in the “greatest possible danger” to humanity – the prospect of its extinction. This warning, like much of the early nonproliferation rhetoric, drew its urgency from the legacies of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Perhaps the starkest indication of the gravity of the stakes emerged during the Cuban missile crisis of October 1962. For 13 days, the world teetered on the edge of nuclear annihilation until the Soviet Union withdrew its missiles from Cuba in exchange for the secret withdrawal of U.S. missiles from Turkey. During those long days, U.S. and Soviet leaders – and external observers – witnessed how quickly the risks of global destruction could escalate.

Crafting the grand bargain

In the wake of such “close calls” – moments where nuclear war was narrowly averted due to individual judgment or sheer luck – diplomacy accelerated.

Negotiations on a treaty to control nuclear proliferation continued at meetings of the Eighteen Nation Disarmament Committee in Geneva from 1965 to 1968. While the enduring horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki helped to drive the momentum, national interests largely shaped the talks.

There were three groups of negotiating parties. The United States was joined by its NATO allies Britain, Canada, Italy and France – which only observed. The Soviet Union led a communist bloc containing Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Poland and Romania. And there were nonaligned countries: Brazil; Burma, now known as Myanmar; Ethiopia; India; Mexico; Nigeria; Sweden, which only joined NATO in 2024; and the United Arab Republic, now known as Egypt.

For the superpowers, a treaty to limit the spread of the bomb was as much a strategic opportunity as a moral imperative.

Keeping the so-called “nuclear club” small would not only stabilize international tensions, but it would also cement Washington’s and Moscow’s global leadership and prestige.

U.S. leaders and their Soviet counterparts therefore sought to promote nonproliferation abroad. Perhaps just as important as ensuring nuclear forbearance among their adversaries was preventing a cascade of nuclear proliferation among allies that could embolden their friends and spiral out of control.

Standing apart from these Cold War blocs were the nonaligned countries. Many of them approached the atomic age through a humanitarian and moral lens. They demanded meaningful action toward nuclear disarmament to ensure that no other city would suffer the tragic fate of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The nonaligned countries refused to accept a two-tiered treaty merely codifying inequality between nuclear “haves” and “have-nots.” In exchange for agreeing to forgo the bomb, they demanded two crucial commitments that shaped the resulting treaty into what historians often describe as a “grand bargain.”

The nonaligned countries agreed in the treaty to permit the era’s existing nuclear powers – Britain, China, France, the Soviet Union (later Russia) and the United States – to temporarily maintain their arsenals while committing to future disarmament. But in exchange, they were promised peaceful nuclear technology for energy, medicine and development. And to reduce the risks of anyone turning peaceful nuclear materials into weapons, the treaty empowered the International Atomic Energy Agency to conduct inspections around the world.

Legacies and limits

The treaty entered into force in 1970 and with, 191 member nations, is today among the world’s most universal accords. Yet, from the outset, its provisions faced limits. Nuclear-armed India, Israel and Pakistan have always rejected the treaty, and North Korea later withdrew to develop its own nuclear weapons.

In response to evolving challenges, such as the discovery of Iraq’s clandestine nuclear weapons program in the early 1990s, International Atomic Energy Agency safeguard efforts grew more stringent. Many countries agreed to accept nuclear facility inspections on shorter notice and involving more intrusive tools as part of the initiative to detect and deter the development of the world’s most powerful weapons. And the countries of the world extended the treaty indefinitely in 1995, reaffirming their commitment to nonproliferation.

The treaty represents a complex compromise between morality and pragmatism, between the painful memories of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and hard-edged geopolitics. Despite its many imperfections and its de facto promotion of nuclear inequality, the treaty is credited with limiting nuclear proliferation to just nine countries today. It has done so through civilian nuclear energy incentives and inspections that give countries confidence that their rivals are not building the bomb. Countries also put pressure on each other to obey the rules, such as when the international community condemned, sanctioned and isolated North Korea after it withdrew from the treaty and tested a nuclear weapon.

But the treaty continues to face serious challenges. Critics argue that its disarmament provisions remain vague and unfulfilled, with some scholars contending that nonnuclear countries should exit the treaty to encourage the great powers to disarm. Nuclear-armed countries continue to modernize – and in some cases, expand – their arsenals, eroding trust in the grand bargain.

The behavior of individual countries also points to strains on the treaty. Russia’s persistent nuclear threats during its war on Ukraine show how deeply possessors may still rely on these weapons as tools of coercive foreign policy. North Korea continues to wield its nuclear arsenal in ways that undermine international security. Iran might consider proliferation to deter future Israeli and U.S. strikes on its nuclear facilities.

Still, I would argue that declaring the treaty to be dead is simply premature. Critics have predicted its demise since the treaty’s inception in 1968. While many countries have growing frustrations with the existing system of nonproliferation, most of them still see more benefit in staying than walking away from the treaty.

The treaty may be embattled, but it remains intact. Worryingly, the world today appears far removed from the vision of avoiding nuclear catastrophe that Hiroshima and Nagasaki helped awaken. As nuclear dangers intensify and disarmament stalls, moral clarity risks fading into ritual remembrance.

I believe that for the sake of humanity’s future, the tragedies of the atomic bombings must remain a stark and unmistakable warning, not a precedent. Ultimately, the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty’s continued relevance depends on whether nations still believe that shared security begins with shared restraint.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

80 years since Hiroshima, a world without nuclear weapons is still possible

(RNS) — Instead, the US government is pouring billions more of our tax dollars into building a new generation of nuclear weapons and planning to resume nuclear testing.

FILE - The destruction at Hiroshima, Japan, caused by the atomic bomb dropped on the city in August 1945. (Photo courtesy of Creative Commons)

Bridget Moix

August 1, 2025

(RNS) — Eighty years ago, the United States detonated atomic bombs for the first time in history, ushering in a devastating new era of war and threat. The first explosion occurred during the Manhattan Project’s Trinity test in New Mexico in July 1945, followed weeks later by the U.S. bombings of Hiroshima on Aug. 6 and Nagasaki on Aug. 9.

The Trinity test created radiation fallout affecting unprotected communities across the state and beyond. The attacks on civilian populations in Japan killed hundreds of thousands of men, women and children and leveled most of both cities. The testing and the bombings left legacies of disease, mortality and environmental contamination affecting communities for decades to come.

This year, U.S. survivors of nuclear weapons testing — known as “downwinders” — won a major victory in Congress with the expansion of the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act. The expansion brings long-excluded groups into the program, including those in Utah, New Mexico, Idaho and Arizona — some exposed as early as 1945 at the Trinity Test site. It also covers communities harmed by Manhattan Project waste in parts of Missouri, Tennessee, Kentucky and Alaska.

Their advocacy turned grief into action, and action into law.

This is a major milestone, but it’s also bittersweet. Some impacted communities were left out of the expansion because it cost “too much.” These exclusions are unjust and unacceptable. There is still work to do. But this victory was only made possible by decades of grassroots leadership from directly impacted communities. They spoke out, even when no one was listening.

The hibakusha — Japanese survivors of the U.S. bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki — have spent decades bearing witness to the horrors of nuclear war. Yet unlike U.S. downwinders, they have received little recognition or recompense from the U.S. government. Many in the U.S. foreign policy establishment continue to justify the deliberate targeting of civilians as a necessary step to end World War II. But such acts are morally indefensible and widely condemned under international law. As history professor Richard Overy of the University of Exeter notes, Japan was already on the brink of surrender due to blockade and urban warfare. An alternative path was possible.

Eighty years later, the devastation of nuclear weapons is still with us, and the threat they pose to human life is greater than ever. In January, the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists moved its “Doomsday Clock,” a symbol created by scientists to illustrate humanity’s proximity to global catastrophe, one second closer to midnight, or 89 seconds away from nuclear holocaust. As tensions between the U.S. and Russia persist and the war in Ukraine drags on, the potential for these indiscriminate weapons being used again — by intention, miscommunication or accident — continue to rise.

For years, faith groups have condemned these weapons as immoral and called for their abolition. Quakers, my own community, have long advocated for a world free of nuclear weapons, though you do not have to be a pacifist to see the danger these weapons pose to us all.

Instead of leading the world to reduce the nuclear threat, the U.S. government is pouring billions more of our tax dollars into building a new generation of nuclear weapons and planning to resume nuclear testing. This is also provoking more nuclear risks and undermining nonproliferation efforts. The Trump administration’s recent bombing of Iranian nuclear sites interrupted renewed diplomatic talks between the U.S. and Iran on a deal to restrain the development of these weapons and ensure international monitoring. The attacks did little to destroy Iran’s nuclear capabilities and only heightened tensions between Iran’s government, Israel and the U.S.

As the world reflects on the devastation wreaked by nuclear weapons for 80 years, we must continue to imagine and work for a world free of nuclear weapons and the threat they pose to humanity. That world may seem far away right now, but we can keep advocating for it.

Specifically, we can urge our members of Congress to recommit to diplomacy and nuclear nonproliferation.

The New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) remains the last major arms control agreement between the United States and Russia, placing critical, verifiable limits on both countries’ nuclear arsenals. But this treaty is set to expire in 2026, and with it, the transparency and guardrails that have helped prevent catastrophe for more than a decade.

Congress must support efforts like H.Res. 100 and S.Res 61, which call for the U.S. to pursue a follow-on treaty to New START and reaffirm its commitment to nuclear arms control. Such an agreement between the U.S. and Russia — the world’s two largest nuclear arsenals — could lay the groundwork for future multilateral agreements, acting as a powerful first step toward bolder nuclear abolition efforts.

As Terumi Tanaka, survivor of U.S. atomic bombing of Nagasaki and recent recipient of the 2024 Nobel peace prize, reminds us, “It is the heartfelt desire of the Hibakusha that, rather than depending on the theory of nuclear deterrence, which assumes the possession and use of nuclear weapons, we must not allow the possession of a single nuclear weapon.”

Diplomacy is our best defense against the unimaginable. Preventing a new arms race requires courage, foresight and leadership. Eighty years after the first mushroom cloud rose over New Mexico, we owe it to past and future generations to reject a world governed by fear and to build a future rooted in cooperation, accountability and peace.

(Bridget Moix is the general secretary of the Friends Committee on National Legislation and leads two other Quaker organizations, Friends Place on Capitol Hill and the FCNL Education Fund. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

Hiroshima

A warning from history: ‘This is what is going to happen to you’

Wednesday 6 August 2025, by Allen Myers

Eighty years ago, the United States government exploded over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki the only two nuclear bombs ever used in wartime against a civilian population. Never before in human history had a single weapon caused such widespread death and destruction.

A report by engineers and scientists of the Manhattan Project (the US project that developed the bombs), based on a 1946 investigation in both cities, estimated that more than two-thirds of Hiroshima’s 90,000 buildings had been destroyed or badly damaged, including everything within one mile (1.6km) of ground zero, aside from a few structures made from reinforced concrete. In Nagasaki, buildings with reinforced concrete walls 25cm thick, more than 600 metres from ground zero, collapsed.

In Hiroshima, the bomb destroyed 26 of 33 firefighting stations, killing or badly injuring three-fourths of their personnel. It killed or badly wounded more than 1,800 of 2,400 nurses and medical orderlies, and left only 30 of 298 registered doctors able to treat survivors. Many of those not killed immediately burned to death in the subsequent firestorm, or drowned trying to escape it in rivers, or died within hours or days of radiation sickness.

The Manhattan Project report estimated that Hiroshima suffered 135,000 casualties—more than half its population—and Nagasaki 64,000 out of a population of 195,000. Both figures were underestimates because they did not include prisoners of war and other foreigners, such as thousands of Korean forced labourers present in both cities.

People who survived the immediate effects of the blasts were not necessarily safe. Two years after the bombings, there was a notable increase in the rate of leukaemia among initial survivors, which spiked four to six years later. The largest number of victims were children.

But while the power of the bombs was unprecedented, the mass slaughter of civilians was anything but new. All of the major powers involved in the war carried out or assisted deliberate massive attacks on civilians: Japan’s 1937-38 Rape of Nanjing, which killed up to 300,000 Chinese civilians and disarmed soldiers; the German Blitz of Britain, which killed around 43,000; the US-British firebombing of Dresden, which destroyed 90 percent of the city’s centre and killed at least 25,000 people, many of whom died of suffocation as all available oxygen was consumed by the conflagration; there are numerous other examples.

If the ruling classes of the warring countries had a similar amoral sense (the belief that any slaughter they engaged in was justified), the course of the war and a technological lead gave the US rulers the opportunity and confidence that they could get away with the greatest atrocities. In the last year of the war, US air raids systematically destroyed Tokyo, taking advantage of the large number of highly combustible houses to create firestorms. Early on 10 March 1945, some 279 US bombers firebombed most of eastern Tokyo, killing 90,000 to 100,000 people and leaving a million homeless; the destruction was even greater than that of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In part, the atomic bombs were more “efficient” than earlier air raids: in the 10 March raid on Tokyo, fourteen US aircraft were shot down. But strategic decisions directed against the Soviet Union were a more important consideration. This was summed up by South Africa’s Nelson Mandela in 2003:

“Fifty-seven years ago, when Japan was retreating on all fronts, they [the US] decided to drop the atom bomb in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Killed a lot of innocent people, who are still suffering from the effects of those bombs. Those bombs were not aimed against the Japanese. They were aimed against the Soviet Union. To say, look, this is the power that we have. If you dare oppose what we do, this is what is going to happen to you.”

Looking forward to the next war between the “allies” was also evident in a memo issued to British airmen on the night of the attack on Dresden:

“The intentions of the attack are to hit the enemy where he will feel it most, behind an already partially collapsed front, to prevent the use of the city in the way of further advance, and incidentally to show the Russians when they arrive what Bomber Command can do.”

When the Soviet Union tested its first atomic bomb in August 1949, considerably earlier than the US expected, the US quickly recognised a need to “outcompete” its rivals, beginning serious steps toward developing a thermonuclear (hydrogen) bomb. An investigation of the desirability and possibility of building the new bomb, chaired by Robert Oppenheimer, the physicist who had headed the Manhattan Project’s Los Alamos laboratory, concluded: “The extreme danger to mankind inherent in the proposal wholly outweighs any military advantage”.

The extreme danger to the human race was less important than the military needs of imperialism. US President Harry Truman approved the development of the hydrogen bomb in January 1950. The first thermonuclear bomb was tested on 1 November 1952. It was more than 450 times as powerful as the Nagasaki bomb, with an explosive force of 15 megatons of TNT.

The US thermonuclear monopoly lasted less than a year, the Soviet Union testing its first hydrogen bomb in the following August. And although 15 megatons was an already unimaginable force, the Soviet government in 1961 tested a bomb with a force of 50 megatons. Within the test zone, brick buildings 55km from ground zero were destroyed. The heat from the blast was capable of causing third-degree burns 100km away.

That test was, in part, an experiment designed to discover whether there was any inherent limit to the potential explosive power of a nuclear bomb. There wasn’t; in a report for the US Atomic Energy Commission, physicists Enrico Fermi and Isidor Isaac Rabi concluded that hydrogen bombs potentially have “unlimited destructive power”.

At the time, the 50-megaton thermonuclear bomb was too heavy to be carried by any existing missile or aeroplane. But technological “progress” has since created hydrogen bombs light enough for ten or more to be carried by a single missile.

And yet, today, all of the nine nuclear-armed states—United States, Russia, France, United Kingdom, China, India, Pakistan, Israel and North Korea—are attempting to “modernise” their arsenals, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, “upgrading existing weapons and adding newer versions”.

SIPRI calculates the world nuclear arsenal at 12,241 warheads. “An estimated 3,912 of those warheads were deployed with missiles and aircraft ... Around 2,100 of the deployed warheads were kept in a state of high operational alert on ballistic missiles. Nearly all of these warheads belonged to Russia or the USA, but China may now keep some warheads on missiles during peacetime.”

In 2010, the USA and Russia agreed to a treaty (New Start) to limit their nuclear stockpiles and the number of warheads deployed on strategic missiles. But that treaty expires next February, and neither side has shown any real interest in renewing it, so the number of warheads able to be fired in minutes if not seconds is expected to increase.

Despite most nuclear arsenals being labelled “deterrents” by those who wield them, no government keeps nuclear bombs for peaceful purposes; they are intended for use when military and political conditions make that seem advisable. While the US and Russia have the biggest stockpiles, does anyone imagine that moral or humanitarian considerations would have more of a restraining influence on Benjamin Netanyahu than they have on Donald Trump or Vladimir Putin? At least one minister within the Israeli government has publicly advocated using an atomic bomb against Gaza—on which Israel has already inflicted destruction comparable to what was done to Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In short, the danger of capitalist governments letting loose nuclear weapons has not significantly decreased since 1945; in many respects, it is greater.

6 August 2025

Source: Red Flag.

Attached documentsa-warning-from-history-this-is-what-is-going-to-happen-to_a9113.pdf (PDF - 912.7 KiB)

Extraction PDF [->article9113]

Allen Myers is a longtime Australian activist who writes for Red Flag.

International Viewpoint is published under the responsibility of the Bureau of the Fourth International. Signed articles do not necessarily reflect editorial policy. Articles can be reprinted with acknowledgement, and a live link if possible.

U.S. Atomic Bombings Didn’t Save Lives or End the War

August 6, 2025

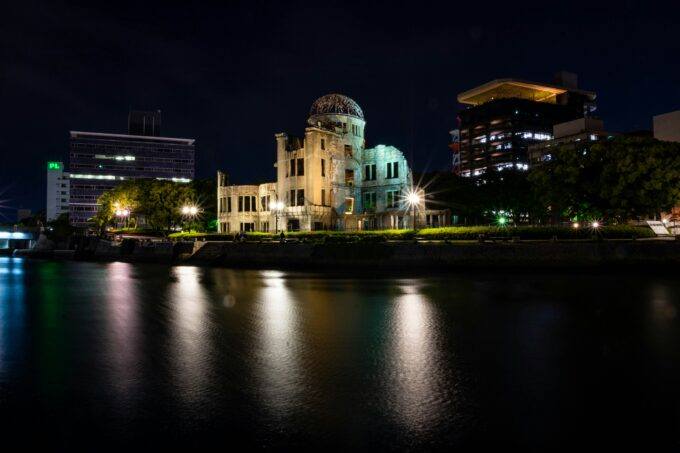

Atomic Bomb Dome, Hiroshima, Japan. Image by Alessandro Stech.

August 6 and 9 are the 80th anniversaries of the U.S. atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The killing of 140,000 civilians at Hiroshima was the effect of detonating a 60-million-degree Celsius explosion (ten thousand times hotter than the surface of the sun) over the city. Richard Rhodes’ The Making of the Atomic Bomb reported, “People exposed within half a mile of the … fireball were seared to bundles of smoking black char in a fraction of a second as their internal organs boiled away…”

The use of atomic bombs was rationalized after-the-fact using myths that transformed the burning of children into a positive good. President Truman and government propagandists justified the attacks claiming they “ended the war” and “saved lives” ⸺ stories still believed today ⸺ but, as historian Gar Alperovitz has demonstrated in The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb, and the Architecture of an American Myth the pretext of “saving lives” was fabricated.

General Dwight Eisenhower, who had been the Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, notes in his book Mandate for Change that he told Secretary of War Henry Stimson at the July 1945 Potsdam Conference that he opposed using the bomb because it was “no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives.” Ike told Stimson, “Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary.”

Broad declassification of wartime documents and personal diaries has made it possible to learn the facts. One key example, reported by Gar Alperovitz reports in The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb, is the April 30, 1946 report by the Intelligence Group of the War Department’s Military Intelligence Division (“Use of Atomic Bomb on Japan”), first discovered in 1989, which concluded “almost certainly that the Japanese would have capitulated upon the entry of Russia into the war…” which occurred on August 8. Japan surrendered a week later.

Researchers have found so much that refutes official propaganda, that the historian of the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, J. Samuel Walker, reported in the winter 1990 edition of the journal Diplomatic History: “The consensus among scholars is that the bomb was not needed to avoid an invasion of Japan and to end the war within a relatively short time.”

Dozens of leaders who ran the war agree. Winston Churchill wrote in his history of WWII, “It would be a mistake to suppose that the fate of Japan was settled by the atomic bomb. Her defeat was certain before the first bomb fell.”

Admiral William Leahy, the Chief of Staff to Presidents Roosevelt and Truman, declared in his memoir I was there, “The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender. The use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. I was not taught to make war in that fashion, and wars cannot be won by destroying women and children.”

Major General Curtis LeMay, who directed the devastating incendiary destruction of Japan’s 67 largest cities prior to August 1945, was more emphatic. Asked by a reporter at a Sept. 20, 1945 press conference, “Had they [Japan] not surrendered because of the atomic bomb?” Gen. LeMay declared, “The atomic bomb had nothing to do with the end of the war at all.”

Gen. “Hap” Arnold, commander of the Army Air Force, wrote in Global Mission (1949), “It always appeared to us that atomic bomb or no atomic bomb the Japanese were already on the verge of collapse.”

Likewise, Brig. Gen. Bonner Fellers reported in Reader’s Digest, “Obviously … the atomic bomb neither induced the emperor’s decision to surrender nor had any effect on the ultimate outcome of the war.” And the renown Gen. Douglas MacArthur, said “he saw no military justification for the dropping of the bomb.”

Religious and cultural leaders contemporaneously condemned the attacks, as on March 5, 1946, when the Federal Council of Churches issued a statement signed by 22 prominent Protestant religious leaders saying in part, “the surprise bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are morally indefensible. … Both bombings, moreover, must be judged to have been unnecessary for winning the war.”

Nuclear weapons are still protected by lies like “limited nuclear war.” This month’s anniversaries remind us to rebel against them, to demand that the United States apologize to Japanese and Korean survivors and their descendants for the crime; that the U.S. abandon its nuclear attack plans and preparations (deterrence); and that it finally stands-down and eliminates the crown jewels and poisoned foundation of all government waste, fraud, and abuse ⸺ nuclear weapons.

No, Nuking Cities Did Not Save Lives

It’s oddly encouraging that the New York Post had to bring up its kookiest right-wing propagandist on Friday to argue that nuking Hiroshima and Nagasaki saved lives. It’s almost as if the New York Times’ kookiest right-wing propagandist’s claiming that killing Palestinians is not genocide had to be one-upped by the Post. It’s even more encouraging that the Post felt obliged to expand the usual definition of “lives” to include the lives of Japanese people, claiming that nuking people saved not only U.S. lives but also Japanese lives — an argument it would have been very hard to find even being attempted during the early decades of this myth.

But it isn’t true that claims that nukes saved lives or nukes ended the war are only made by fringe crackpots. Those claims may be fading out among serious historians, but they are basic accepted fact to the general public, even the most educated sections of the general public; so they continue popping up like zombies in books and articles whose authors seem to have no idea they’re even writing anything controversial, much less utterly debunked. (The Post calls it “one of the most controversial historical questions in American history.”)

The argument in the Post (quoting an author named Richard Frank) is this:

“Not only has no relevant document been recovered from the wartime period, but none of them,” he writes of Japan’s top leaders, “even as they faced potential death sentences in war-crimes trials, testified that Japan would have surrendered earlier upon an offer of modified terms, coupled to Soviet intervention or some other combination of events, excluding the use of atomic bombs.”

Well here’s a relevant document. Weeks before the first bomb was dropped, on July 13, 1945, Japan had sent a telegram to the Soviet Union expressing its desire to surrender and end the war. The United States had broken Japan’s codes and read the telegram. Truman referred in his diary to “the telegram from Jap Emperor asking for peace.” President Truman had already been informed through Swiss and Portuguese channels of Japanese peace overtures as early as three months before Hiroshima. Japan objected only to surrendering unconditionally and giving up its emperor, but the United States insisted on those terms until after the bombs fell, at which point it allowed Japan to keep its emperor. So, the desire to drop the bombs may have lengthened the war. The bombs did not shorten the war.

It’s odd for the Post to build its case entirely on the absence of a certain type of testimony by proud Japanese defendants facing trials for their lives with zero motivation to admit that the Japanese government had been wanting to surrender, and for the Post to completely omit the testimony of all U.S. authorities.

Defenders of nuking cities may now claim the nukes saved lives, but at the time the bombs were not even intended to do any such thing. The war ended six days after the second nuke, six days into the Russian invasion of Japan. But the war was going to end anyway, without either of those things. The United States Strategic Bombing Survey concluded that, “… certainly prior to 31 December, 1945, and in all probability prior to 1 November, 1945, Japan would have surrendered even if the atomic bombs had not been dropped, even if Russia had not entered the war, and even if no invasion had been planned or contemplated.”

One dissenter who had expressed this same view to the Secretary of War and, by his own account, to President Truman, prior to the bombings was General Dwight Eisenhower. Under Secretary of the Navy Ralph Bard, prior to the bombings, urged that Japan be given a warning. Lewis Strauss, Advisor to the Secretary of the Navy, also prior to the bombings, recommended blowing up a forest rather than a city. General George Marshall apparently agreed with that idea. Atomic scientist Leo Szilard organized scientists to petition the president against using the bomb. Atomic scientist James Franck organized scientists who advocated treating atomic weapons as a civilian policy issue, not just a military decision. Another scientist, Joseph Rotblat, demanded an end to the Manhattan Project, and resigned when it was not ended. A poll of the U.S. scientists who had developed the bombs, taken prior to their use, found that 83% wanted a nuclear bomb publicly demonstrated prior to dropping one on Japan. The U.S. military kept that poll secret. General Douglas MacArthur held a press conference on August 6, 1945, prior to the bombing of Hiroshima, to announce that Japan was already beaten.

The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Admiral William D. Leahy said angrily in 1949 that Truman had assured him only military targets would be nuked, not civilians. “The use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender,” Leahy said. Top military officials who said just after the war that the Japanese would have quickly surrendered without the nuclear bombings included General Douglas MacArthur, General Henry “Hap” Arnold, General Curtis LeMay, General Carl “Tooey” Spaatz, Admiral Ernest King, Admiral Chester Nimitz, Admiral William “Bull” Halsey, and Brigadier General Carter Clarke. As Oliver Stone and Peter Kuznick summarize, seven of the United States’ eight five-star officers who received their final star in World War II or just after — Generals MacArthur, Eisenhower, and Arnold, and Admirals Leahy, King, Nimitz, and Halsey — in 1945 rejected the idea that the atomic bombs were needed to end the war. “Sadly, though, there is little evidence that they pressed their case with Truman before the fact.”

On August 6, 1945, President Truman lied on the radio that a nuclear bomb had been dropped on an army base, rather than on a city. And he justified it, not as speeding the end of the war, but as revenge against Japanese offenses. “Mr. Truman was jubilant,” wrote Dorothy Day. We have to remember that in the U.S. media of the time, killing more Japanese people was decidedly preferable to killing fewer, and required no justification of supposedly saving lives or ending wars. Truman, the guy whose action is being defended and whose diary is being carefully ignored, made no such claims, as he was not doing restrospective propaganda.

So, why then were the bombs dropped?

Presidential advisor James Byrnes had told Truman that dropping the bombs would allow the United States to “dictate the terms of ending the war.” Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal wrote in his diary that Byrnes was “most anxious to get the Japanese affair over with before the Russians got in.” Truman wrote in his diary that the Soviets were preparing to march against Japan and “Fini Japs when that comes about.” The Soviet invasion was planned prior to the bombs, not decided by them. The United States had no plans to invade for months, and no plans on the scale to risk the numbers of lives that the Post will tell you were saved.

Truman ordered the bombs dropped, one on Hiroshima on August 6th and another type of bomb, a plutonium bomb, which the military also wanted to test and demonstrate, on Nagasaki on August 9th. The Nagasaki bombing was moved up from the 11th to the 9th to decrease the likelihood of Japan surrendering first. Also on August 9th, the Soviets attacked the Japanese. During the next two weeks, the Soviets killed 84,000 Japanese while losing 12,000 of their own soldiers, and the United States continued bombing Japan with non-nuclear weapons — burning Japanese cities, as it had done to so much of Japan prior to August 6th that, when it had come time to pick two cities to nuke, there hadn’t been many left to choose from.

Here’s what the Post claims was accomplished by killing a couple of hundred thousand people and commencing the age of apocalyptic nuclear danger:

“The end of the war made unnecessary a US invasion that could have meant hundreds of thousands of American casualties; saved millions of Japanese lives that would have been lost in combat on the home islands and to starvation; cut short the brief Soviet invasion (that alone accounted for hundreds of thousands of Japanese deaths); and ended the agony that Imperial Japan brought to the region, especially a China that suffered perhaps 20 million casualties.”

Notice that the Post feels obliged to blame (at the time it would have been credit) the Soviet invasion with killing hundreds of thousands of Japanese people, even while claiming, pace Truman, that it did not influence the Japanese decision to surrender. Notice also that the only alternative to the war ending after the nukes, in this view, would have been the war continuing for a great long time costing millions of Japanese lives. But the facts above do not bear this out. The 2025 propagandist is disagreeing with the consensus of the leaders of his beloved military in 1945.

Why is he doing that?

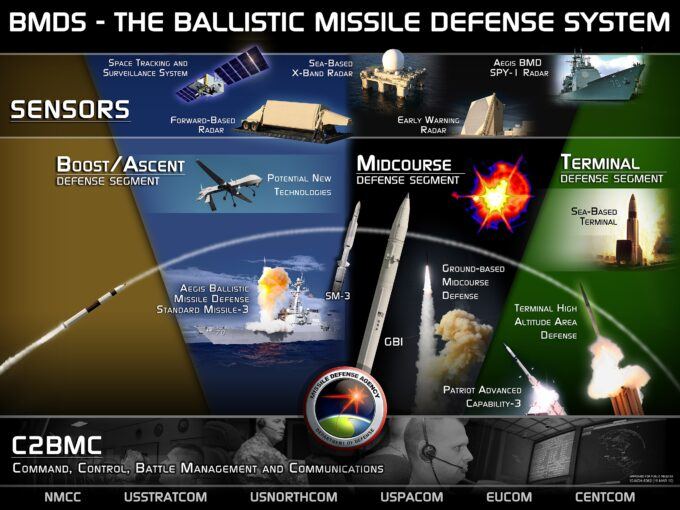

He concludes with his motivation: “This is why President Donald Trump’s vision of a Golden Dome to protect the U.S. from missile attack is so important, and why we need a robust nuclear force to deter our enemies.”

Here is a different view of what World War II tells us about a Golden Dome.

- First published at World Beyond War.

No comments:

Post a Comment