Historical Association Finds Long-Sought Wreck of 19th-Century Schooner

The prolific wreckfinders at the Wisconsin Historical Society and the Wisconsin Underwater Archaeology Association have unveiled another historic Great Lakes shipwreck. Over the weekend, the association announced that it has discovered the long-sought wreck of the F.J. King, which foundered in Lake Michigan in 1886.

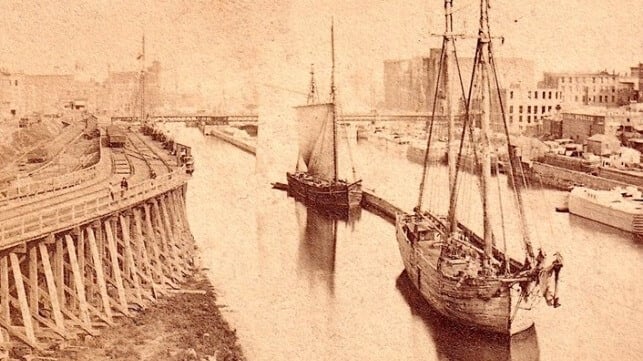

The F.J. King was a wooden cargo schooner built in 1867 for bulk trades on the Great Lakes. Her dimensions allowed her to transit the Welland Canal, expanding her opportunities for trading.

On September 14, 1886, F.J. King was under way with a load of iron ore, headed for Chicago. Off the Door Peninsula, she was hit by a gale and seas of up to 10 feet. In the pounding, her wooden hull began to admit water. The crew pumped by hand in an attempt to keep her afloat, but within a few hours it became apparent that the ship would sink. The master ordered abandon ship, and all the crew got off safely. At about 0200 hours on the 15th, the schooner sank below bow-first; the survivors were rescued by another schooner and delivered safely to Baileys Harbor. There were no fatalities.

The location of the wreck remained a mystery, and a point of local curiousity. The master's last reported position didn't line up with visual observations of the vessel's masts from the local lighthouse keeper. Clues and hints to the site's whereabouts showed up periodically - like bits of wreckage that came up in fishing nets - but decades of searching yielded nothing, even after a local club posted a healthy bounty.

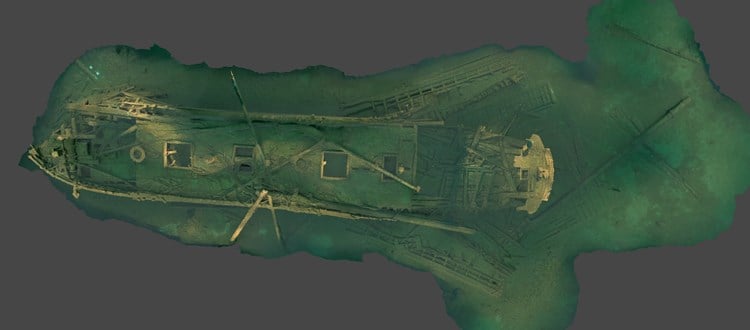

WUAA had a small search grid to run based on the lighthouse keeper's account, but didn't expect to find anything that day. They departed their pier on a trial run to familiarize themselves with a sidescan and a small ROV, and stumbled upon the wreck after two hours of operating. They measured its length on sonar and found it to be 140 feet - about the same as F.J. King. At this point they were pretty sure that they had it, and a quick ROV dive confirmed its identity and its remarkably intact condition.

Composite photo of the wreck site (WUAA)

“We reasoned that the captain may not have known where he was in the 2AM darkness, but the lighthouse keeper’s course and distance to the masts were probably accurate," said principal investigator Brendon Baillod. The wreck position was about half a mile from the lighthouse keeper's estimate.

Great Lakes wreckfinding is an active area of archaeological pursuit, and the Wisconsin Underwater Archaeology Association has discovered four other wrecks in the last three years. A similar group in Michigan, the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society, has found countless more. There are an estimated 1,500 shipwrecks in Lake Michigan alone

Marine Archaeologists Salvage Artifacts From Titanic's Sister Ship

Marine archaeologists in Greece have recovered artifacts from the wreck of the HMHS Britannic, a sister ship of the Titanic and the largest vessel lost during the First World War.

Britannic was built at Harland & Wolff at the height of WWI and delivered in late 1915. While she had been ordered as a passenger ship, but she was immediately pressed into service as a hospital ship in Royal Navy service, requisitioned for transporting casualties of the costly and ultimately unsuccessful Gallipoli campaign.

She made three voyages, including the evacuation of the Dardanelles in January 1916. After that, she was paid off and dispatched to Belfast for a refit as a passenger liner - but was immediately recalled to duty in the middle of the conversion and dispatched to the Mediterranean again for an additional two voyages as a hospital ship.

Her design was modified to benefit from the safety lessons of the Titanic's sinking, including a double hull in way of the engineering compartments and raising up her watertight bulkheads another six decks. The revised design was intended to keep the vessel afloat with six compartments flooded. In the event of an abandon-ship scenario, she carried extra lifeboats and could in theory reposition them from one side to the other to enable full launch with a heavy list.

But these changes were not enough to save her from meeting the same fate as Titanic. The Brittanic's career only lasted about 11 months in total: on the morning of November 21, 1916, she hit a German mine in the Kea Channel in the Cyclades. There were no patients on board, just the normal crew complement of 674 seafarers and 392 medical staff.

Though only four compartments initially flooded, the ship listed and began downflooding through open portholes in lower-deck wards, which had been left ajar for ventilation. A failed watertight door between two boiler rooms added to the problem.

The master navigated the vessel towards shore, hoping to effect an intentional grounding. During this evolution, two lifeboats were launched without authorization on the port side and were demolished by the exposed port propeller, killing 30 people. Ultimately the screws were stopped and the abandon-ship order given; 35 lifeboats made it away, and 1036 personnel survived.

Brittanic lay on the bottom in shallow water, her position unknown until 1975, when she was rediscovered by Jacques Cousteau. This year, in May, a British team of archaeological divers revisited the site to conduct a recovery operation, with support from Greek authorities. Despite challenging site conditions, they resurfaced historical artifacts from the wreck, including ceramic tiles, cabin fittings, a navigation lamp, a bell, and a passenger's personal binoculars.

All of the recovered items were taken to specialized underwater antiquities labs in Athens for proper treatment. The ultimate plan is to put them on display in Piraeus' new National Museum of Underwater Antiquities.

No comments:

Post a Comment