INDIA

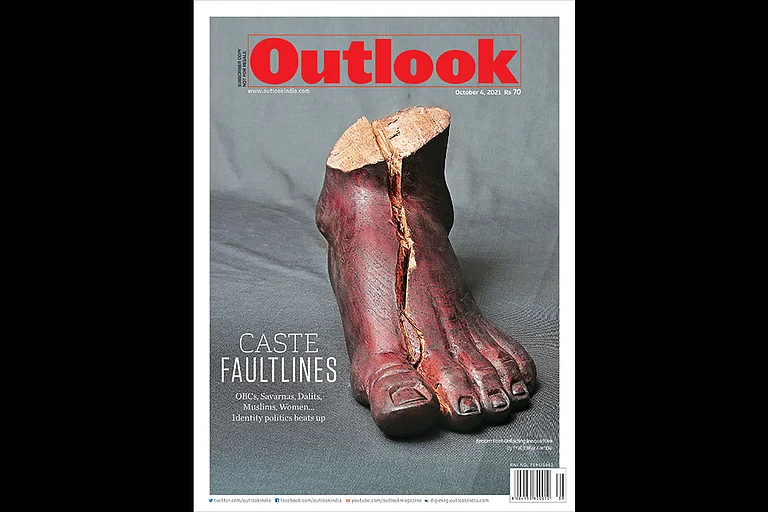

Anatomy of Humiliation: Caste Violence in Constitutional Era

Understanding violence against Dalits necessitates moving beyond a mere enumeration of physical atrocities to defining the systemic denial of dignity and the imposition of comprehensive social exclusion. The persistence of caste discrimination, despite the constitutional abolition of untouchability, reveals that caste operates as a profound societal architecture—a “state of the mind”—that actively facilitates dehumanisation. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s seminal critique identified Hinduism as a structure fostering beliefs inherently unjust and oppressive.

Historical practices underscore the institutional roots of this humiliation, which are alarmingly mirrored and even innovated upon in contemporary India. Accounts from the Peshwa rule describe how untouchables were prevented from using public streets due to the polluting effect of their shadow; in Poona, they were forced to wear a broom attached to their waist to sweep away their footprints. Visuals of such a humiliating practice has been immortalised by Dalit writers and poets (Dalit shahirs)—performers in the late 19th and 20th centuries—that created a body of literature and theatre known as Dalit jalse.[1] Such ritual enforcement of segregation persists today in modernised forms of humiliation. This includes incidents where a 12-year-old Dalit boy died by suicide after being locked in a cowshed and shamed for accidentally entering an upper-caste house in Himachal Pradesh (October 2025), or the horrific case of a 14-year-old Dalit child forced to consume his own faeces (July 2020).

CJP is dedicated to finding and bringing to light instances of Hate Speech, so that the bigots propagating these venomous ideas can be unmasked and brought to justice. To learn more about our campaign against hate speech, please become a member. To support our initiatives, please donate now!

The continuance –in the 21st century — of these ritualistic forms of violence, seven decades after India’s independence, confirms a profound failure of the constitutional promise of equality. The violence is often preceded by symbolic degradation—the imposition of dominant caste thought and perception—which acts as a necessary pre-condition for the subsequent material and physical violence. This structural denial of humanity maintains the cultural and ritual authority of the caste system, fundamentally resisting constitutional mandates.

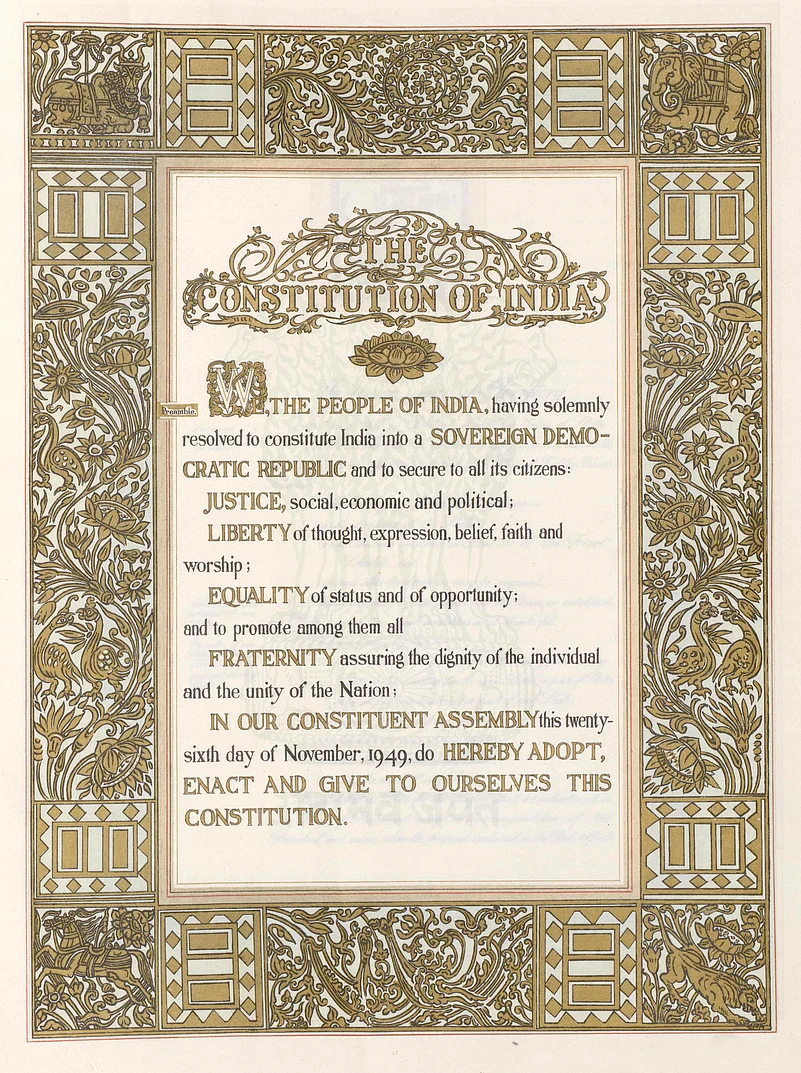

In 1950, the Constitution of India promised a radical rupture: the abolition of untouchability (Article 17), equality before the law (Article 14), and a vision of dignity that sought to transcend birth-based hierarchy. Even then, as Indians celebrated a vision of equality and non-discrimination, there was vocal resistance (in the Constituent Assembly) to a complete and total abolition of Caste itself at the time of the Constituent Assembly debates; finally, as a compromise, Article 17 was enacted. Seven decades later, the persistence and intensification of violence against Dalits across regions and institutions suggest that even the limited promise remains incomplete.

In recent years, this crude form of violence and exclusion has acquired new visibility — and new legitimacy. Incidents of caste humiliation no longer remain confined to villages or agrarian conflicts; they permeate public spaces, reflective of the re-legitimisation of this othering by the dominance of the political ideology ruling at the Centre and over a dozen states: Schools, cities, social media, and even the judiciary’s symbolic space have been breached: it is as if a shrill messaging is being broadcast of the casteist majoritarian regime in power; that caste exclusion and hierarchy is not simply justified but will be violently imposed. When an advocate of India’s apex court “dares” flinging a shoe at the present Chief Justice of India (CJI), a Buddhist and this is followed by singular racial abuse online, it shatters the comforting belief that institutional achievement insulates against stigma. Such episodes illuminate a wider social truth: caste not only continues to function as India’s deepest grammar of power, adapting to modern structures rather than disappearing within them. Caste resurgence is the order of the day, being re-imposed, brutally by this dispensation. What India is witnessing is the classic form of counter-revolution.

This article maps this regression. Mostly drawing upon recent incidents documented in 2025 —including those in Thoothukudi, Panvel, Meerut, and Madhya Pradesh—it reconstructs what can be termed the “new architecture of caste attacks.” Major incidents before 2025 have also been included to show a pattern. Violence and exclusion today occur through overlapping arenas: the village, the city, the school, the digital sphere, and the state itself. Each arena reveals how caste’s social logic survives despite constitutional guarantees.

Notably, all the incidents referred to in this piece has been provided in detail in a separate document below:

The Ascending Hierarchy of Attack: From ritual to institutional apex

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar envisioned the Constitution as a path towards both a moral and social revolution. The formal abolition of untouchability was meant not merely to criminalise discrimination but to destroy its social roots. Yet Ambedkar warned in the Constituent Assembly that “political equality” without “social and economic equality” would leave democracy vulnerable to caste hierarchy’s return.

The decades following independence saw significant legislative advances—the Protection of Civil Rights Act (1955), the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act (1989)—but these were accompanied by obdurate police and administrative non-application and followed by a persistent social backlash. Caste privilege adapted: open exclusion gave way to subtler forms of humiliation and violence disguised as defence of “tradition,” “honour,” or “religion.”

The post-2014 political climate added a new layer. In 1999, India had already experienced a glimpse of what was in store to come, when the National Democratic Alliance (in its first form) had the RSS-inspired Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) only as a minority. Yet, following the 2002 Gujarat pogrom, the ghastly lynching of five Dalit men in the village of Dulina, Jhajjar district, Haryana, after being falsely accused of cow slaughter, on October 15, 2002, shook the nation. A spate of such crimes continued and were documented.[2] The complicity of the police and the alleged involvement of far right organisations like the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) was part of the details recorded.

The ascent of cultural majoritarianism, the mainstreaming of “Sanatani” rhetoric, and the weaponisation of social media have together normalised casteist discourse while weakening institutional checks. The result is not the re-emergence of caste, but its reconfiguration through new technologies, idioms, and legitimations.

The analysis of caste violence must recognise its escalating and diversifying trajectory. The attacks are no longer confined solely to remote rural pockets but have ascended a hierarchy of space and institution, moving from localised ritual control to sophisticated psychological control in urban institutions, and finally culminating in explicit political and ideological confrontation with the nation’s highest constitutional offices.

The sheer volume of reported cases underscores the crisis. According to National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data, in 2023, 57,789 cases of crimes against SCs were registered, a slight 0.4% increase from 57,582 cases in 2022. Looking at a wider period reveals a substantial escalation. A study by the Dalit Human Rights Defenders Network noted a 177.6% rise in crimes against SCs between 1991 and 2021.

This violence is not exclusive to villages; urban centres exhibit alarming rates. As per the statistics, Uttar Pradesh (15,130 cases) reported the highest number of crimes against SCs, followed by Rajasthan (8,449), Madhya Pradesh (8,232), and Bihar (7,064). Despite these statistics, the true incidence is severely underreported. Research suggests that only about 5% of assaults are officially recorded, often due to police indifference, bribery demands, or outright dismissal of complaints, particularly rape reports.

The structural progression of violence can be categorised across distinct spheres, illustrating the systemic nature of exclusion in the modern Republic.

Table 1: Typology of Caste Atrocities: The continuum of humiliation

Ground Zero: Traditional sites of visceral violence (village to street)

Despite rapid urbanisation, the village remains the most enduring theatre of caste violence. In rural Madhya Pradesh, Dalit families were beaten and their seeds confiscated for cultivating common land (July 2025); in Chhatarpur, twenty families faced social boycott for accepting prasad from a Dalit neighbour (January 2025). Similar patterns appear across Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Bihar.

1. Controlling the Essentials: Land, water, and ritual space

In rural India, the primary mechanisms of caste control revolve around denying access to essential resources and ritual spaces, thereby enforcing physical and ritual segregation. Access to water, a non-negotiable human right, remains violently conditional upon caste status. The case of the 8-year-old Dalit boy in Barmer, Rajasthan, who was severely beaten and hung upside down for touching a water pot intended for upper castes, is a visceral demonstration of this control (September 2025). Similarly, the suicide of the 12-year-old Dalit boy in Himachal Pradesh was a direct consequence of humiliation for trespassing on upper-caste property (October 2025).

Ritual spaces, intended to be public, are often violently guarded to enforce untouchability. Dalits have been barred from offering prayers at a Durga Puja Pandal in Madhya Pradesh (September 2025) and violently assaulted for attempting to enter a temple during a religious procession in Churu, Rajasthan (September 2025). The Madras High Court was recently compelled to intervene and issue instructions to the Tenkasi administration regarding the equitable distribution of water due to persistent caste bias, highlighting how essential services are used as weapons of caste control (July 2025). The requirement for police to guard a Dalit wedding in Gujarat, sometimes using drones, underscores the fragility of civil rights protection when faced with entrenched local hierarchy (May 2025).

2. Policing Dalit Assertion: Rites of passage and mobility

Caste violence is inherently triggered not just by deviation from purity codes but by the assertion of equality and self-respect. This is most vividly manifest in attacks aimed at policing Dalit mobility and rites of passage, particularly wedding processions (baraats).

The act of a Dalit groom riding a horse, traditionally reserved for dominant castes, often leads to violence. Incidents across Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan involve grooms being pulled off their horses and guests being attacked (February 2025). This violence becomes ideologically intensified when Dalit identity is asserted. In Mathura, a Dalit baraat was attacked with stones and sticks after the Thakur community objected to the playing of songs related to Dr. Ambedkar and the Jatav community (July 2025). This deliberate suppression of public visibility and self-respect confirms that the violence is preventative, aimed at suppressing any public display of Dalit parity, thereby revealing the fundamentally anti-democratic nature of caste control.

Furthermore, intimate choices that threaten the integrity of caste endogamy are met with brutal force. Honor killings and extreme violence against inter-caste relationships are widespread. A Dalit youth in Tamil Nadu was hacked to death over an inter-caste relationship, with his girlfriend implicating her own family. In another incident, a Dalit boy in Tamil Nadu was stripped, beaten, and subjected to caste slurs for meeting a Vanniyar girl. (July 2025) The alleged honour killing of a Dalit man in Pune over his marriage to a Maratha woman, characterised by his family as a caste murder, confirms that this policing of reproductive choices transcends the rural-urban divide (February 2025).

3. The geography of forced servitude and political disobedience

Economic empowerment and political participation by Dalits are routinely met with retributive violence designed to re-establish feudal control. Violence often flares up when Dalits refuse forced labour or assert their rights over agricultural resources. In Madhya Pradesh, a Dalit youth was brutally beaten and his house set ablaze for refusing to work as a labourer (August 2025). Other attacks have involved dominant caste men snatching seeds and assaulting Dalit families cultivating their land (June 2025).

The targeting extends explicitly to Dalit political empowerment. A Dalit woman Sarpanch and her husband in Rajasthan were attacked with an axe over disputes regarding MNREGA road work (June 2025). This illustrates that achieving political mobility through constitutional offices is tolerated only as long as it does not challenge the economic and social dominance of local power structures. When a Dalit woman attempts to administer public projects (MNREGA), the challenge to local caste authority is met with physical terror, fundamentally linking economic development to caste subjugation.

The Modern Crucible: Institutionalised discrimination (city to school)

Cities were once imagined as caste’s antithesis—sites of anonymity and merit. Yet attacks on Dalit wedding processions in Agra and Meerut, and stone-pelting during Ambedkar-Jayanti rallies in Rajasthan, show that urbanity merely relocates caste antagonism.

Public celebrations become battlegrounds for visibility. The sight of a Dalit groom on a horse, or the sound of Ambedkarite songs, is treated as provocation. The violence is performative: it polices who may occupy the street, who may celebrate publicly, and which forms of joy are legitimate. In several districts, local authorities have begun escorting Dalit weddings with police and drones—an image at once tragic and telling.

Urban caste violence underscores how modern citizenship collides with inherited status. It also demonstrates the selective nature of state protection: preventive deployment rather than structural reform, treating equality as an event to be managed, not a norm to be lived.

1. The Cost of Merit: Caste in elite academia

Caste discrimination has infiltrated the highest echelons of Indian society, shifting the site of exclusion from the village field to the university lecture hall, resulting in a disturbing incidence of student suicides. Elite educational institutions, far from being meritocratic safe spaces, operate under a constant atmosphere of systemic, psychological violence against marginalised students. This structural violence is enacted through ridicule, ostracism, administrative bias, and academic sabotage.

Between November and December 2025 itself, three deaths of Dalit students across India underscored the lethal intersection of caste discrimination, institutional neglect, and structural exclusion in educational spaces. On November 6, a 19-year-old Dalit student of Deshbandhu College, Delhi University, and sister of JNUSU presidential candidate Raj Ratan Rajoriya, was found dead in her Govindpuri rented flat, with BAPSA alleging grave procedural lapses by the police, absence of medical personnel and female officers, and broader “institutional apathy” by Delhi University, including its failure to provide adequate hostel accommodation for marginalised students, forcing them into unsafe and isolating housing conditions. On November 20, an 18-year-old Dalit student, S Gajini, from Government Arignar Anna Arts College in Villupuram, succumbed to injuries ten days after attempting suicide, allegedly driven by caste-based abuse and assault by men from a dominant caste following a road altercation; despite an FIR under the SC/ST Act, the accused remain unidentified. On December 12, a 17-year-old Dalit student at a DIET institute in Kurnool died by suicide after prolonged distress linked to her struggle with English-medium coursework, highlighting how language barriers, caste location, and lack of institutional academic support continue to disproportionately burden first-generation and marginalised learners.

The environment becomes hostile because of the active weaponisation of meritocracy. Dalit students are frequently taunted as “non-meritorious” or “quota products”. This psychological assault on their intellect and dignity constitutes epistemic violence, a modernised replacement for ritual pollution, turning academic spaces into sites of structural harassment.

Case studies vividly illustrate this pattern:

- Rohith Vemula, 2016 (Hyderabad University)[3]: Vemula’s administrative exclusion, which forced him and four others to sleep in a makeshift “Dalit ghetto,” was recognised by his peers as a modern form of villevarda. While his death sparked a national political movement, the later police closure report attempted to undermine the caste-based motivation by questioning his Scheduled Caste status, thereby reinforcing the pernicious stigma of “fake merit”.

- Darshan Solanki, 2023 (IIT Bombay)[4]: Solanki died by suicide after allegedly facing ostracisation and ridicule from peers for asking basic questions in technical subjects. The institutional response from IIT Bombay, which prematurely denied any caste discrimination before a full inquiry was completed, exemplified institutional denial and refusal to confront endemic caste bias.

This environment of toxic exclusion is responsible for widespread trauma, with reports indicating that 80% of suicides in seven IITs were committed by Dalit students. Furthermore, the bias extends beyond performance, affecting administrative representation. Ten Dalit professors at Bangalore University resigned from their administrative roles, citing discrimination. The perpetuation of this violence reveals a fundamental rigidity: caste acts as a boundary that professional success cannot breach.

Table 2: Manifestations of exclusion in educational institutions

2. Invisible Barriers: Urban exclusion and professional glass ceilings

For Dalits who successfully navigate the hostile academic environment and achieve high professional status, the violence persists, though it adopts subtler, institutionalised forms. This reality demonstrates that economic independence does not translate into the annihilation of caste.

The suicide of Dalit IPS officer Puran Kumar, who questioned unfair promotions and postings, tragically illustrated that rank and wealth do not grant immunity; caste prejudice penetrates the highest echelons of bureaucracy (October 2025). Similarly, a Dalit Assistant Professor at SV Veterinary University was subjected to public humiliation when his chair was allegedly removed, forcing him to perform his duties while sitting on the floor (June 2025).

Discrimination is also structural in the dynamic urban private sector. Research indicates that job applicants with a Dalit name face significant discrimination, having approximately two-thirds the odds of receiving an interview compared to dominant-caste Hindu applicants with equivalent qualifications. This demonstrates that social exclusion is not a rural remnant but is actively practiced in the most modern sectors of the economy. This systemic sabotage of upward mobility means that educational and professional achievements merely shift the form of violence from physical assault to debilitating psychological and institutional harassment.

3. The digitalisation of hate and incitement

The rise of digital media has provided a new, pervasive medium for the normalisation and amplification of caste hatred. Based on a 2019 report by the human rights organisation Equality Labs, caste-based hate speech was found to make up 13% of the hate content reviewed on Facebook India. This digital sphere has facilitated the de facto normalisation of caste-hate speech and is recognised as a medium for oppressing and humiliating Dalits.

This toxic online envionment is actively utilized by right-wing extremist organisations, which have grown in prominence, sometimes using platforms like Instagram to promote hateful content and even fundraising. Major digital platforms demonstrated a historical disregard for addressing this issue, taking years to incorporate “caste” as a protected characteristic in their hate speech policies, and often failing to list it as an option in their reporting forms.

This digital rhetoric creates a climate of ideological validation that can incite physical violence. Harassment campaigns against high-profile Dalit figures, such as the Chief Justice of India, function as a coordinated form of symbolic violence intended to normalise the rejection of constitutional equality and test the boundaries of legal impunity.

The Politicalisation of Caste Warfare: The current regime context

Beyond violence lies symbolic appropriation. Dalit culture—its festivals, songs, and icons—is increasingly commodified or sanitised within a homogenised “Sanatani” narrative. The exclusion of India’s tribal President from the Ram Mandir inauguration exemplifies this politics of selective inclusion: representation without recognition.

In West Bengal, the “vegetarianisation” of Durga Puja since 2019 reflects a subtler transformation. Non-Sanatani groups, including many Dalit and Bahujan communities, are labelled “non-sattvic,” their rituals cast as impure. This recoding of religiosity transforms caste into cultural hierarchy.

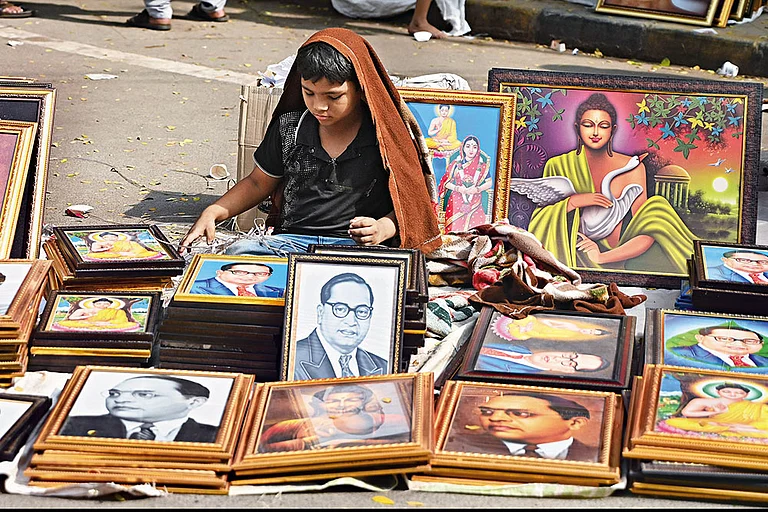

At the same time, Ambedkar’s image is everywhere—on posters, statues, and government programmes—yet his emancipatory thought is domesticated. The appropriation of Ambedkar without the politics of equality amounts to symbolic capture: a neutralised memory that conceals continuing oppression.

Cultural exclusion thus performs two contradictory gestures—erasure and incorporation—both of which depoliticise Dalit assertion while reaffirming upper-caste control over meaning.

1. The Rise of Neo-Traditionalism: Sanatana dharma and exclusion

The period following 2014 has been marked by a significant ideological shift, where the ruling party’s emphasis on Hindu nationalism has provided an explicit political and cultural sanction for traditional caste principles. The concept of Sanatana Dharma has become a central ideological tool. Critics argue that this philosophy inherently justifies and maintains the rigid caste hierarchy, contrasting sharply with the constitutional ideals of liberty and equality. Any critique of caste discrimination, such as those made by Udhayanidhi Stalin regarding the system prevalent in Sanatana Dharma, is immediately framed by the dominant political ecosystem as an attack on Hinduism, aimed at polarising the electorate.

This ideological polarisation was directly responsible for the attempted shoe attack on Chief Justice B.R. Gavai (October 2025). The attacker, Rakesh Kishore, specifically shouted, “Sanatan ka apmaan nahi sahenge” (We will not tolerate the insult of Sanatan Dharma). This action linked a perceived anti-Hindu judicial stance (related to the Khajuraho deity ruling) directly to the caste identity of the judge. The incident functioned as an ideological declaration: constitutional morality, when used by a Dalit judge to challenge majoritarian religious claims, is deemed an “insult” that must be violently resisted, placing religious tradition above constitutional law.

2. Selective appropriation of Ambedkar and Hindutva strategy

The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and its political affiliates have engaged in a sustained and deliberate political strategy to appropriate the legacy of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, primarily to secure electoral gains and neutralise the profound ideological threat his philosophy poses to the foundational principles of Hindutva.

This strategy involves selectively invoking aspects of Ambedkar’s life, such as his conversion to Buddhism, while simultaneously minimising or ignoring his radical denunciation of Hinduism as being incompatible with democratic values. The attempt is to portray Ambedkar as a “Hindu social reformer” rather than a foundational critic of the caste system, thereby drawing Dalit politics into a unified, but hierarchical, “Hindu” fold. This co-option strategy is further highlighted by political attempts to link Ambedkar to RSS founders, despite historical evidence to the contrary.

The tactical use of Ambedkar’s image is often contradicted by ground realities. For instance, symbolic gestures are performed alongside reported policy failures, such as the denial of scholarships to 3,500 Dalit students in Uttar Pradesh, forcing public condemnation from Dalit leaders (June 2025). This gap between rhetoric and action confirms that the strategy is one of symbolic integration designed to neutralise dissent, rather than a genuine commitment to substantive social justice.

3. Symbolic constitutional exclusion

The pattern of exclusion extends to high constitutional functionaries from marginalised communities. The noticeable absence of President Droupadi Murmu, an Adivasi (Scheduled Tribe) and the constitutional head of state, from the inauguration of the highly politicised Ram Mandir in Ayodhya was widely criticised by opposition leaders, who connected it to her earlier exclusion from the Parliament building inauguration.

Although President Murmu belongs to the Adivasi community, the incident forms part of a larger pattern of ritual exclusion of marginalised constitutional authorities from highly faith-based state functions. The event, serving as a defining moment for the new majoritarian ideology, suggests a reordering of constitutional hierarchy. The exclusion of the head of state, particularly one from a marginalised background, implies that ritual purity and majoritarian religious identity are positioned to supersede constitutional hierarchy and the democratic principle of representation.

The Assault on the Constitutional Apex: Targeting the judiciary

1. The CJI Incident: From judicial remark to caste attack

The attempted shoe attack on Chief Justice of India B.R. Gavai stands as the most explicit act of caste-based political defiance directed at the core institutions of the Republic. The violence was ideologically motivated, following the CJI’s remarks during a hearing about a Vishnu idol in Khajuraho.

The caste dimension was immediately clear. The ideological defence of the attacker, Rakesh Kishore, who invoked Sanatan Dharma, and the support of influential right-wing figures like YouTuber Ajeet Bharti, who called Gavai a “lousy, undeserving judge” and accused him of “anti-Hindu sentiments”, establishes a crucial political point. The attack was not aimed at judicial competence but at the perceived “anti-Sanatan” judicial decision, rooted in the judge’s Dalit identity. This confrontation establishes that challenging ritual caste authority through constitutional interpretation is now publicly deemed an act of ideological treason.

2. Impunity and state response

The response of the state apparatus to the assault and subsequent incitement has set a dangerous precedent of selective justice. The attacker, Rakesh Kishore, was released shortly after questioning because the CJI declined to press charges. Kishore subsequently expressed no remorse for his actions.

Crucially, those who digitally incited further violence were also handled with remarkable leniency. YouTuber Ajeet Bharti, who made provocative remarks about the CJI and allegedly suggested actions such as spitting on the judge, was briefly taken in for questioning by Noida Police but was not arrested and was later released.

This lenient approach towards both the physical attacker and the digital instigator demonstrates a deep political hesitation to punish ideologically driven attacks rooted in majoritarian caste sentiment, even when directed at the highest judicial authority. This establishes a political environment that minimises the gravity of such threats, potentially intimidating the judiciary and compromising its ability to enforce social justice laws without fear of retribution.

Gendered Violence and Custodial Deaths: The deepest layer of impunity

Caste and gender intersect to produce some of India’s most brutal crimes. Dalit women continue to face disproportionate sexual violence, often as retribution for asserting dignity or property rights. Cases from Uttar Pradesh’s Sitapur district (2023) and Madhya Pradesh’s Sidhi forest region (2024) illustrate patterns where rape is both punishment and warning.

Custodial deaths compound the pattern. Dalit men arrested on minor charges have died in custody under suspicious circumstances, their families alleging torture. Investigations are often perfunctory, medical reports delayed, and officers reinstated. Such cases demonstrate how state power fuses with social prejudice, converting constitutional guardians into instruments of caste discipline.

The intersection of caste and gender is absent from mainstream criminal jurisprudence. The law individualises crime; caste violence is collective. Without recognising this collective dimension, justice remains procedural rather than transformative.

Regional Patterns: The southern paradox

Contrary to common perception, official data and recent reportage show high incidence of atrocities in southern states—Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Kerala—regions long celebrated for social reform. The Thoothukudi incident (2023) and the string of attacks in Tirunelveli district (over 1,000 cases in five years) reveal both persistence and visibility.

This “southern paradox” has sociological roots: assertive Dalit movements and higher reporting rates coexist with dominant-caste backlash. Greater literacy and media presence ensure documentation but not necessarily deterrence. The violence is thus both a measure of progress (assertion) and of resistance (repression).

The Post-2014 Inflection: Normalisation and silence

The last decade marks a qualitative shift. Three developments stand out:

- Cultural majoritarianism: The language of “Sanatan Dharma” has become a political grammar through which caste is re-inscribed as divine order. Public discourse valorises hierarchy as heritage.

- Digital propagation: Organised online ecosystems amplify caste-coded slurs and mobilise outrage with unprecedented speed.

- Institutional silence: From police stations to ministries, selective inertia signals tacit endorsement. Silence becomes policy.

This triad—rhetoric, technology, and silence—has rendered caste violence socially negotiable. The constitutional ethos of equality competes with a cultural ethos of graded dignity.

The Constitutional Abyss: Implications for the Indian republic

1. The Failure of the SC/ST (PoA) Act: Legal protections as fiction

The rampant escalation of violence highlights the systemic failure of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989 (PoA Act). Designed as a potent legal shield, the Act is continually undermined by institutional resistance and poor enforcement, leading to low conviction rates.[5]

Police inaction is endemic; research documents the prevalent practice of police failing to register FIRs or prematurely closing cases through “Final Reports”. Despite the Supreme Court’s, clear directive that FIR registration is mandatory for cognizable offenses, police show a “differential stance” on enforcing the PoA Act compared to other statutes, demonstrating systemic bias in justice delivery.

Moreover, the state apparatus frequently operates as an agent of caste oppression. Incidents include police custody deaths of Dalit individuals, police brutality against a Dalit woman in Haryana, and officers being booked for assaulting a retired Dalit official. This pattern demonstrates that the constitutional mandate to protect Dalits is often betrayed by the very instruments of state power, rendering legal protections fictional.

The SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act 1989 and its 2015 Amendment remain India’s most potent instruments against caste violence, yet enforcement deficits persist. The act mandates immediate FIR registration, establishment of special courts, and protection of victims. Ground reports show chronic under-registration, downgrading of charges, and police bias.

Judicial interpretation oscillates between protection and dilution. The Supreme Court’s 2018 Subhash Kashinath Mahajan judgment introduced safeguards against “false cases,” effectively softening arrest provisions until partially reversed by Parliament. This episode revealed how institutional anxiety about misuse can overshadow concern for victims’ safety.

At stake is not merely criminal justice but constitutional morality—Ambedkar’s phrase for the ethical framework that must animate state action. When police or courts treat caste violence as routine, they erode that morality. The Republic then survives in form but not in substance.

2. The conceptual meaning of exclusion and humiliation

The pervasive violence is structurally maintained through exclusion, which is the combined outcome of deliberate deprivation and systemic discrimination, preventing Dalits from exercising full economic, social, and political rights.

Humiliation serves as a continuous psychological weapon, seeking to deny the basic humanity of the Dalit individual and enforce ritual hierarchy. Whether through being stripped and beaten, forced into humiliating acts, or subjected to taunts questioning their merit, the goal remains the denial of constitutional dignity. Dr. Ambedkar’s formulation established that democracy requires the foundational principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity. The evidence suggests that when Dalits attempt to live a democratic life—by asserting social equality (riding a horse), achieving academic merit (joining an elite institution), or claiming high constitutional office (CJI)—they are met with structural violence and, frequently, death. This structural opposition confirms that the traditional social order fundamentally rejects the core ethical commitments of the Indian Constitutional Republic.

Conclusion: Safeguarding constitutional morality

Philosophers from Avishai Margalit to Axel Honneth define humiliation as the denial of recognition essential to personhood. Caste violence operates precisely through such denial. Its power lies not only in inflicting pain but in publicly authorising inequality. When a Dalit child is beaten for entering a temple, or when a Chief Justice is abused online, the message is continuous: certain bodies remain conditional citizens. Humiliation thus functions as pedagogy—teaching both victim and perpetrator the limits of equality. To counter it requires more than punishment; it requires re-socialisation—a transformation of cultural consciousness that law alone cannot produce.

The investigation into the hierarchy of attacks against Dalits, tracing the violence from ritual control in the village to ideological confrontation at the highest constitutional levels, confirms a severe crisis of constitutional morality in India. The nature of caste warfare has transitioned from covert rural brutality to overt, high-profile ideological confrontations in the urban and judicial spheres. This escalation is profoundly enabled by a political climate that prioritises majoritarian traditionalism over the egalitarian principles of the Constitution. The targeting of a Dalit Chief Justice, sanctioned by ideological rhetoric and met with institutional leniency, signifies that the foundational democratic tenet of equality is now under explicit, active threat.

To address this existential challenge, a set of structural and policy reforms is necessary to transform nominal guarantees into substantive equality:

- Mandatory and independent police accountability: Legislation must be introduced to mandate the immediate and unconditional registration of FIRs under the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act for all cognizable offenses, coupled with the establishment of independent police accountability commissions with the authority to prosecute officers who violate or fail to enforce the Act.

- Criminalising institutional caste bias: Stringent anti-discrimination laws, backed by criminal penalties, must be implemented across all educational, corporate, and governmental institutions to address structural and psychological harassment, ending the systemic institutional denial of caste discrimination.

- Digital accountability for incitement: Robust legal and regulatory measures are necessary to hold social media platforms accountable for the unchecked proliferation of caste-based hate speech and the incitement of violence, recognising it as a direct threat to public order and democratic principles.

The escalation of caste violence against Dalits—from the exclusion of a child from water access to the political assault on the Chief Justice—is a gauge of the Republic’s health. If the judiciary cannot be protected from attacks based on the caste identity of its leader, the entire legal and democratic framework built to secure social justice stands compromised.

More than seventy-five years after independence, the Indian Republic stands at a moral crossroads. Formally, it is a constitutional democracy; substantively, it remains stratified by caste. The incidents chronicled in 2025 itsef—stretching from rural Madhya Pradesh to the Supreme Court’s digital corridors—suggest not an aberration but a continuum.

The question is therefore not whether caste survives, but how the state and society have adapted to its survival. The new architecture of attacks—spanning villages, cities, institutions, and cyberspace—reveals that violence and exclusion now coexist comfortably with democratic form.

Ambedkar warned that “Democracy in India is only a top-dressing on an Indian soil which is essentially undemocratic.” The task ahead is to deepen the soil—to cultivate a culture where dignity is not negotiable, where equality is not episodic, and where the law’s promise finally becomes social reality. Until then, every assault on a Dalit body, image, or word remains an assault on the Constitution itself.

References

Indian colleges are hotbeds of casteism. How can they do better? – The News Minute https://www.thenewsminute.com/news/indian-colleges-are-hotbeds-casteism-how-can-they-do-better-176683

Caste and the Dalits: An Introduction – Global Ministries https://www.globalministries.org/resource/caste-and-the-dalits-an-introduction/

A clash of ideologies: Why Ambedkar and Hindutva are poles apart – The Polity https://thepolity.co.in/article/173

Hate Speech against Dalits on Social Media – Brandeis Library Open Access Journals https://journals.library.brandeis.edu/index.php/caste/article/download/260/61/1048

View of Hate Speech against Dalits on Social Media: Would a Penny Sparrow be Prosecuted in India for Online Hate Speech? https://journals.library.brandeis.edu/index.php/caste/article/view/260/61

Caste-hate speech – International Dalit Solidarity Network

https://idsn.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Caste-hate-speech-report-IDSN-2021.pdf

Atrocities on Dalits in Contemporary India Even After 75 Years of Indian Independence https://ijfans.org/uploads/paper/5af7bf7ae1851636fe726333533b1c8b.pdf

Dalit scholar’s protest exposes casteism in India’s higher education – FairPlanet https://www.fairplanet.org/story/dalit-scholars-protest-exposes-casteism-in-indias-higher-education/

IIT-Bombay Dalit student death | Senior says Darshan Solanki felt alienated by roommate, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/iit-bombay-dalit-student-death-senior-says-darshan-solanki-felt-alienated-by-roommate/article66611752.ece

Attack on CJI: Union MoS Athawale seeks SC/ST Act charges as BJP does a tightrope walk https://indianexpress.com/article/political-pulse/shoe-attack-cji-mos-athawale-sc-st-act-bjp-10298249/

Ram Mandir Invitation: NCP Leader Raises Concerns about Draupadi Murmu’s Exclusion,

Rohith Vemula: Foregrounding Caste Oppression in Indian Higher Education Institutions, https://www.epw.in/engage/article/rohith-vemula-foregrounding-caste-oppression

IIT Student Suicides: Curse Of Caste On Campus? | Left, Right & Centre – YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fhDhIhQiRWQ

How many lives will it take before India acknowledges dominant caste hegemony in educational institutes? – Citizens for Justice and Peace

https://cjp.org.in/how-many-lives-will-it-take-before-india-acknowledges-dominant-caste-hegemony-in-educational-institutes/

India’s caste system: ‘They are trying to erase dalit history. This is a martyrdom, a sacrifice’ https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jan/24/student-suicide-untouchables-stuggle-for-justice-india

Suicide by Dalit students in 4 years – The Hindu https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/Madurai/suicide-by-dalit-students-in-4-years/article2425965.ece

Unveiling The Tragic Link: Caste Discrimination And Suicides In Higher Education https://theprobe.in/stories/unveiling-the-tragic-link-caste-discrimination-and-suicides-in-higher-education/

Urban Labour Market Discrimination – GSDRC

https://gsdrc.org/document-library/urban-labour-market-discrimination/

Indian women, Dalits, Adivasis, Muslims face discrimination in earnings and jobs: Oxfam report https://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/2022/Sep/15/indian-women-dalits-adivasis-muslims-face-discrimination-in-earnings-and-jobs-oxfam-report-2498476.html

An Introduction to Right-Wing Extremism in India – ScholarWorks at UMass Boston, https://scholarworks.umb.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1809&context=nejpp

For far-right groups in India, Instagram has become a place to promote violence, report shows – PBS

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/for-far-right-groups-in-india-instagram-has-become-a-place-to-promote-violence-report-shows

Online caste-hate speech: Pervasive discrimination and humiliation on social media, https://teaching.globalfreedomofexpression.columbia.edu/resources/online-caste-hate-speech-pervasive-discrimination-and-humiliation-social-media

Udayanidhi Stalin’s Critique of Sanatana Dharma – Two Articles – Janata Weekly

https://janataweekly.org/udayanidhi-stalins-critique-of-sanatana-dharma-two-articles/

The Eternal Discrimination Of Sanatana Dharma – Madras Courier, https://madrascourier.com/opinion/the-eternal-discrimination-of-sanatana-dharma/

Dr.Ambedkar, Sanatan Dharma and Dalit Politics – Countercurrents, https://countercurrents.org/2023/09/dr-ambedkar-sanatan-dharma-and-dalit-politics/

(PDF) The attack on the CJI and the shadow of caste – ResearchGate https://www.researchgate.net/publication/396310357_The_attack_on_the_CJI_and_the_shadow_of_caste

Right-wing influencer Ajeet Bharti faces scrutiny online after ‘shoe attack’ on CJI Gavai, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/after-shoe-attack-on-cji-right-wing-youtuber-ajeet-bharti-faces-scrutiny-online-101759830247046.html

RSS and Ambedkar: A Camaraderie That Never Existed – Janata Weekly, https://janataweekly.org/rss-and-ambedkar-a-camaraderie-that-never-existed/

From criticism to praise: How RSS changed stance on Ambedkar – Deccan Herald, https://www.deccanherald.com/india/from-criticism-to-praise-how-rss-changed-stance-on-ambedkar-3492843

Appropriating Ambedkar: Effort to merge Left and Ambedkarite politics – The Hindu, https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/appropriating-ambedkar-effort-to-merge-left-and-ambedkarite-politics/article8500076.ece

RSS At 100 And The Philosophy Of A Nation’s Unmaking – OpEd – Eurasia Review, https://www.eurasiareview.com/08102025-rss-at-100-and-the-philosophy-of-a-nations-unmaking-oped/

Who Is Ajeet Bharti? YouTuber Questioned After Controversial Comments On CJI Shoe Attack https://zeenews.india.com/india/who-is-ajeet-bharti-youtuber-questioned-after-controversial-comments-on-cji-shoe-attack-2969348.html

Why did Noida Police question Ajeet Bharti? What he commented on CJI BR Gavai after ‘shoe attack’ | Latest News India – Hindustan Times

https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/why-did-noida-police-question-ajeet-bharti-what-he-commented-on-cji-br-gavai-after-shoe-attack-101759894807122.html

Prof Abhay Dubey on Ajit Bharti Arrested for Inciting Violence Against CJI Gavai after Shoes Hurled – YouTube

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DqpJ8s7HZhk

YouTuber Ajeet Bharti Taken in for Questioning After Remarks on CJI Shoe Incident, Released Later – LawBeat

https://lawbeat.in/news-updates/youtuber-ajeet-bharti-taken-in-for-questioning-after-remarks-on-cji-shoe-incident-released-later-1533340

‘Final Reports’ under Sec-498A and the SC/ST Atrocities Act | Economic and Political Weekly, https://www.epw.in/journal/2014/41/commentary/final-reports-under-sec-498a-and-scst-atrocities-act.html

Dalits and Social Exclusion: An Overview – International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR)

https://www.ijsr.net/archive/v8i7/ART20199584.pdf

India Exclusion Report 2013-2014 – Selected caste extracts

https://idsn.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/India-Exclusion-Report-2013-Selected-caste-extracts.pdf

The Death of a Dalit in a Democracy – Caste – The India Forum, https://www.theindiaforum.in/caste/death-dalit-democracy

[1] This body of work is also a major source for stories and protest songs (Qawwali) that focus on anti-caste movements and give voice to Dalit struggles wherein the broom and pot would be consistent imagery for this protest tradition.

[2] https://www.hrw.org/reports/2007/india0207/6.htm; https://frontline.thehindu.com/social-issues/article30193600.ece#:~:tex….

[3] https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/we-all-failed-rohith/

[4] https://cjp.org.in/iit-mumbai-report-on-darshan-solanki-death-crucial-e…

[5] https://sabrang.com/cc/archive/2005/mar05/cover.html

Courtesy: Sabrang India

Republic-Day Special:

Contemporary political realities, including centralisation, the use of constitutional provisions, and debates over secularism, continue to test the promises of Justice, Liberty, Equality and Fraternity embedded in the opening words: “We, the People of India.”

Ainnie Arif

Updated on: 27 January 2026

The Preamble of India Photo: wiki commons

Summary of this article

India’s Republic was shaped by a long constitutional journey, from the 1929 call for Purna Swaraj and the first Independence Day on January 26, 1930, to the adoption of the Constitution

Foundational debates on equality, federalism and the balance of power between the Centre and the states reflected deep anxieties after Independence.

It produced a Constitution that envisioned a strong Centre while warning against over-centralisation.

Every year, as Republic Day passes, the country is swept up in familiar scenes of celebration: patriotic songs blare from radios, billboards shift to the tricolour, television channels air films steeped in nationalism, and schoolchildren return from Republic Day functions with hands full of ladoos.

Much has been said about Republic Day and its significance, a truth we carried with us long before we learned to grasp its meaning. This year marks India’s 77th Republic Day, commemorating the day the Constitution of India came into force on January 26, 1950, formally establishing the nation as a ‘Sovereign Democratic Republic’.

BR Ambedkar led a key seven-member committee tasked with drafting one of the world’s lengthiest constitutional documents, comprising 395 provisions.

Between India’s independence and the coming into force of the Constitution, a 299-member Constituent Assembly laboured through the upheavals of Partition, communal violence, and the immense task of an ancient civilisation remaking itself into a young, emerging democracy.

Related Content

The Invisibles: Outlook Chronicles How Caste Shapes India

Minimum Marxism: Reclaiming Class Politics

Left’s Caste Blind Spot: Ambedkar And His Criticism of The Circle Of 'Brahmin Boys'

Are We There Yet? Reflections On International Day Of Democracy

The final version of the Constitution was signed by members of the Assembly on January 24, 1950 and came into force two days later with a 21-gun salute and the unfurling of the Indian National Flag by Dr Rajendra Prasad.

The Constitution now lays the foundation of democracy in the country. Yet, the journey from Independence to becoming a Republic was long, shaped by defining national moments and urgent calls for momentum, before it finally found expression in the opening words of the Preamble: “We, the People of India.”

The road to the Republic began with a decisive shift in political demands. In 1929, the Indian National Congress, meeting at its historic Lahore session, adopted the call for Purna Swaraj, or complete independence. This came after negotiations between Indian leaders and the British collapsed over the question of granting India dominion status.

The immediate backdrop was the Irwin Declaration of October 31, 1929, issued by Lord Irwin, then Viceroy of India. Framed as a conciliatory gesture, the declaration sought to reassure Indian nationalists that Britain intended, at some point, to help India attain dominion status within the British Empire. However, conveniently, it offered no clear timeline.

Earlier, the Nehru Report of 1928 had articulated the demand for dominion status, stating that India should enjoy the same constitutional position within the British Empire as Canada or Australia. While such demands had surfaced intermittently in the early decades of the 20th century, they gained wider acceptance only after the Government of India Act, 1919, which reshaped India’s constitutional framework without granting real self-rule.

The Irwin Declaration itself was a brief, five-line statement written in simple, non-legal language. Its vagueness, lack of concrete actions and backlash in England frustrated Indian leaders.

Dr. Ambedkar, The Architect Of Inclusive Indian Nationalism

With only half-promises on the table, the nationalist leadership abandoned the demand for dominion status and instead raised the call for Purna Swaraj—complete and uncompromising independence. January 26, 1930, was declared the first Independence (Swarajya) Day and was to be observed across the country.

At midnight on New Year’s Eve, Jawaharlal Nehru, then President of the Indian National Congress, hoisted the tricolour on the banks of the Ravi in Lahore, marking a turn in India’s freedom struggle that eventually led to its independence and declaration of a Republic almost two decades later, however, not without its contradictions.

Ambedkar, Chairman of the Drafting Committee, himself stated how with India becoming a Republic, “we are going to enter into a life of contradictions. In politics we will have equality, and in social and economic life, we will have inequality.”

In his historic November 25, 1949, speech to the Constituent Assembly, Ambedkar said that the real credit for preparing the draft of the Constitution should first go to B.N. Rao and then to the main draftsman, S.N. Mukherji.

Ambedkar, an advocate of revolutionary state socialism in the Constitution, said: How long shall we continue to deny equality in our social and economic life? If we continue to deny it for long, we will do so only by putting our political democracy in peril.

Another major debate centred on federalism. The Cabinet Mission Plan of 1946 proposed a “federal union” in which the Centre would control only three subjects — defence, external affairs and communication — while the provinces retained all remaining powers. However, Partition in 1947 and its violent aftermath forced a rethinking of this model, leading to the idea of “a federation with a strong Centre”.

This shift was reflected in the Constituent Assembly debates. Veteran Bihar leader Brajeshwar Prasad warned against excessive provincial autonomy, stating, “I am opposed to federalism because I fear that with the setting up of semi-sovereign part-states, centrifugal tendencies will break up Indian unity.”

At the same time, concerns were raised about excessive centralisation. Congress leader T T Krishnamachari urged to outline a three criteria test for states: “states must exercise compulsive power in the enforcement of a given political order”; that “these powers must be regularly exercised over all the inhabitants of a given territory”; and, most importantly, “that the activity of the State must not be completely circumscribed by orders handed down for execution by the superior unit.”

Ambedkar clarified that the “basic principle of federalism” lay in the division of “legislative and executive authority” between the Centre and the states, a division made “not by any law to be made by the Centre but the constitution itself.”

Article 1 of the Constitution describes India as a “Union of States”, notably avoiding the word ‘federal’. Powers are clearly distributed through the Union, State and Concurrent Lists. Yet this arrangement has drawn criticism, particularly because the Centre can dominate the Concurrent List and, under certain conditions, legislate on State List subjects.

Ambedkar cautioned against over-centralisation, warning during the debates, “We must resist the tendency to make it (Centre) strong. It cannot chew more than it can digest. Its strength must be commensurable to its weight.”

These issues acquire even greater relevance in the present context, with the government at the Centre also ruling a majority of states, and with the use of provisions such as Article 359. In an era of superseding political mandates and governments that seem to conveniently amend the Constitution, it becomes important to ask who “we”, as a Republic, truly are — the “we” who give voice to the opening words of the Preamble of India.

9

9Politics of Petals: When A Secular Festival Becomes Inconvenient

At Outlook Magazine, we've asked the question: How far have we come and which are the challenges before the Repubic?

In our issue dated February 28, 2022, we examined the debates on federalism and sought to understand how this struggle has been shaped in recent times.

In 'Renegotiating India’s Federal Compact’, Yamini Aiyar wrote how this model of federalism, with a strong Union and intergovernmental dependence, served India well, despite routine misuse of its powers by the Union.

However, “the emergence of BJP as a single party majority in 2014 has fundamentally changed that federal bargain, both because it has put a pause to the increased presence of regional parties in national politics, but also because the BJP’s penchant for centralisation has opened new sites of contestation in India’s federal bargain. Thus, federalism today is both more vulnerable and unexpectedly more resilient.”

In Right In The Centre, Harish Khare notes the historicity of India's Constitution and its implementation in varying socio-political realities; alongside workability of the States and the Centre.

“As a primary covenant, the Constitution prescribed as well as proscribed working of a few basic relationships: The Union and the States, the Centre and the Periphery, the State and the Citizens, the Majority and the Minorities; and, the Executive-Judiciary; each relationship is defined by limits, to be observed by all constitutional players. The framers had aimed for a dynamic equilibrium as we would undertake the task of cobbling together a modern state and a vibrant political community.”

Another debate revolved around the inclusion of the word secularism. In Outlook Magazine’s November 21, 2022 issue, The Secularism Question, Abhik Bhattacharya writes about the beginning of the debate, with discussions on concepts of secularism to God to Power Politics as A Test Of Indian Secularism.

H.V. Kamath started the discussion by moving an amendment that proposed to start the Preamble with ‘In the name of God’. Following Kamath, Shibban Lal Saksena and Pandit Govind Malviya also moved similar amendments and said that it was under no circumstances ‘anti-secular’ and of ‘narrow, sectarian spirit’ as termed by Pandit H.N. Kunzru. Rather, citing the use of the word ‘God’ in the Preamble of the Irish Constitution, Malviya said that by invoking phrases like “By the grace of the Supreme Being, lord of the universe, called by different names by different peoples of the world”, they were not sanctifying God of any particular religion and hence must not be considered contrary to the spirit of secularism.

SY Quraishi speaks of the viability of the India’s secular tradition and its commitment to diversity in ‘A Walk Through The Several Decades Of Indian Secularism’.

“Constitutional secularism is of immense import to our notions of citizenship, nationality and civic freedom. Apart from the obvious effects that a crisis in secularism is registering in the electoral realm, we must also pay attention to how that crisis is creeping into other sectors of our nation’s life, ranging from our national media to education to the everyday life of a citizen.”

The questions of secularism, its inclusion in the Preamble through a constitutional amendment, and the rise of right-wing politics in India have deeply shaped the functioning of the Republic. These shifts have had tangible consequences, with minorities and marginalised communities often finding themselves struggling to access the Justice, Liberty, Equality and Fraternity promised by the Constitution.

Published At: 26 January 2026