Mamdani’s decisive victory, with over 50% of the votes cast makes him New York’s first South Asian and Muslim mayor of a city of 8.5 million. As Nathan Gusdorf, the Director of the Fiscal Policy Institute, observes, he may well be ‘the most important American socialist to ever hold executive office’. Mamdani isn’t however the first socialist mayor of New York City, nor is he the first to be endorsed by the DSA.

The DSA in 1989 endorsed David Dinkins who became New York’s first African American socialist mayor (1990-1993), in the wake of the great but short-lived political momentum built up by Jesse Jackson’s famous 1988 Rainbow coalition. But the DSA that endorsed Dinkins in the 1990s also supported Israel; it was only in the second decade of the 21st Century that the DSA became an outspoken critic of Israel and denounced it as an apartheid and racist state.

Mamdani is also a strong critic of the racial state of Israel, in a way Dinkins never was. There is, moreover, a qualitative difference in the times to which the two socialist mayors belong. David Dinkins served as mayor when the Soviet Union was collapsing, when the US was celebrating its unipolar geopolitical moment, and when establishment liberals like American political scientist Francis Fukuyama were declaring ‘the end of history’.

Mamdani’s tenure, by contrast, unfolds at a time when US world hegemony is finished; Russia has resurged as a Great Power; and a majority of Americans (those within the Republican Party included) are not only critical of Israeli humanitarian crimes committed in Gaza; they are also questioning the unconditional financial and military support that the US offers Israel. A formidable legitimacy crisis confronts US power and prestige on world-scale, worsened by Trump’s tariff wars on Europe and Asia and his blatant disregard for norms of international law.

Inside the nation, creeping inflation fuels a profound cost of living crisis while violent raids on immigrant neighbourhoods spread fear and anxiety among the labouring masses. Within this conjuncture, Mamdani’s anti-racist politics combines well with his affordability agenda to strike a powerful chord with the working-class majority in the city and in the nation.

WORLD-HISTORICAL FOUNDATIONS OF MAMDANI’S POLITICAL VICTORY

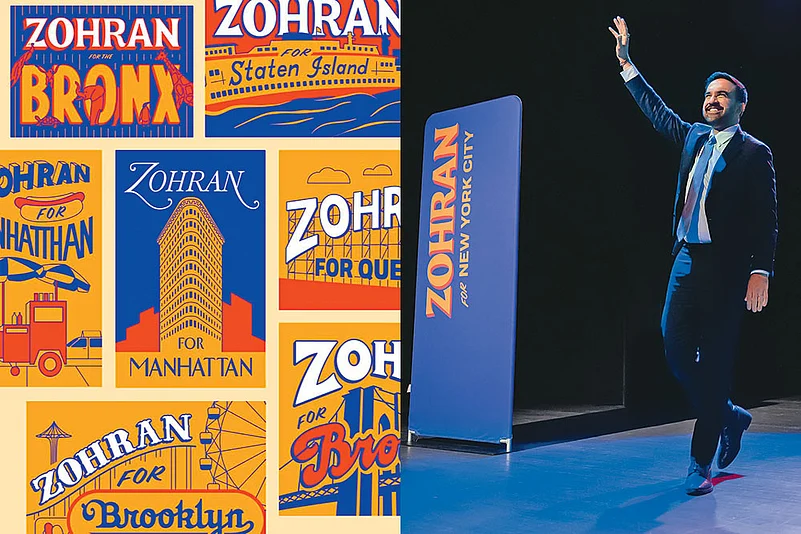

To explain the phenomenal political victory of Zohran Mamdani – first in the June primary and again in the November 2025 general elections – to understand how and why a South Asian socialist secured a mandate from over a million voters, it is best to begin by noting that the city in which the masses elected him to be their mayor, is a city of violent extremes.

Those who visit New York for the first time are dazzled instantly by its tremendous vitality. It is a city that never sleeps – thanks to its fleet of taxi drivers and a subway system that remains accessible through the night. The city’s aura of restless, inexhaustible energy is powered by dreams of upward mobility. These dreams make New York’s working class stretch itself beyond the limits of the working day, working late into the night. The wealthy in the city also work hard, to transform the enormous productive surplus generated by the city’s workers into astronomical profits, much of which concentrates in the towering superstructures of lower Manhattan.

As the epicentre of world-spanning financial networks that converge on Wall Street, New York is home to billionaires who celebrate capitalist ‘creative destruction’ as their destiny, which they identify with that of the city. Alongside its glittering skyscrapers, world-class universities, and first-rate public libraries, New York is also home to an artistic and cultural avant-garde who frequent its majestic museums and vibrant theatres. The city’s green spaces and public parks are urban oases in the hot summer, places to recuperate vital life lost in endless work; and its innumerable bars and high-class restaurants serve global cuisine that charms travelers.

The Statute of Liberty, the global symbol of the American Dream to immigrants from all over the world, remains irresistible to tourists. New York is also headquarters of the United Nations (UN), the symbol of world-government, the place where representatives of the world’s nation-states assemble to uphold norms of international law.

New York is at the same time a city of destructive creation that harshly regulates its poor. It is the most expensive city to live in the world. For working class New Yorkers, whose inexhaustible productivity throws off that tremendous energy that defines the aura of the city, New York is often a nightmare. As it is for the large population of poor households who toil in a twilight zone of existence. Many of the homeless in New York are people with mental illness, criminalised by New York’s police department. The city’s poorest neighborhoods are constantly targets of severe police surveillance. Aggressive policing of African American and Latinx people and their neighbourhoods enforces deep-seated ethno-racial status inequalities.

New York also reflects extraordinary economic inequalities of income and wealth, much more than the US does. Insofar as the Gini coefficient is a reliable index of economic inequality, for the US as a whole, the Gini was 0.486 in 2022; for New York City in the same year, it was 0.555. Among the 10 largest cities in the US, New York City alone holds the dubious distinction of displaying a statistically significant increase, between 2010 and 2022, in the Gini index of inequality.

These inequalities began during the neoliberal turn of the 1970s and widened and deepened during the 1980s and beyond. During those decades the US ruling class responded to its squeeze on profitability – an outcome of competitive catching up by Germany and a Japan-led East Asian region – by actively promoting deregulation and deindustrialisation; by shutting down industrial plants; by downsizing and layoffs; by offshoring and outsourcing production; but, above all, by redirecting itself toward producing and reproducing a speculative financial expansion on world scale, centered on New York City.

Fiscal and monetary policies were deployed to redistribute incomes and wealth toward the top 1% of the city’s financial elite. In the first decade of the 21st century, unregulated financial speculation created the conditions for the great crash of 2007-09 in Wall Street, which was swiftly followed by an equally great bailout (amounting to $750 billion) of the bankers and financiers – by the newly elected Democratic President Barack Obama – responsible for the meltdown in the heartland of global capitalism. The argument for these bailouts was that the banks were ‘too big to fail’. No such bailouts were offered to the working class or the middle class.

The tremendous resentment against bailouts of the capitalist elite birthed the Occupy Wall Street (OWS) movement in New York in September 2011. The movement that began with the occupation of Zuccotti Park – renamed Liberty Park by its occupiers – in the heart of Wall Street, spread like wildfire throughout the US and soon most of the world. Grounded in the deep disaffection of working class and middle class New Yorkers who identified the top 1% as their target, this movement became for three long months, the global symbol of resistance to the neoliberal dogma that ‘there is no alternative’.

From general assemblies in the five boroughs to insurgent rallies and rowdy marches that swept through Wall Street with slogans – ‘no war but class war’; ‘they got bailed out; we got sold out’; ‘they say cutback, we say fight back’ – directed against the ruling elite, the movement was ultimately subject to violent police repression and arrests. If the occupiers of Liberty Park were evicted in December 2011, the movement lived on throughout the city in different social centres.

The restless, irrepressible energy of the Occupy Movement also contributed directly and indirectly to the political expansion of the DSA, which campaigned for Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and identified with the dissenting position within the Democratic party of Bernie Sanders, the Senator from Vermont, whose commitment to working class values in 2016 inspired Mamdani’s campaign.

There are understated overlaps, despite the differences, between the OWS movement and the DSA campaign. Both came out strongly in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement; both demonstrated against arbitrary police violence in the rebellion that followed the murder of George Floyd in 2020, with Mamdani supporting anarchist calls to defund the police. Both were linked, directly or indirectly, with the 2016 Bernie Sander’s campaign against revolting economic inequality. If Sander’s denunciations of the oligarchs who rule America divided Democratic party politics, it was nevertheless unable to sway the Democrats to change course, to abandon the party’s commitments to the ruling political class.

It was left to the Republican candidate Donald Trump to champion the great resentment of a large part of the working-class majority in America (63% of the labour force, according to Michael Zweig) and win the 2016 elections on the promise to ‘drain the swamp’ of corruption that infected national political institutions. Although Trump lost to Joe Biden in part because of his failure to govern the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, the Democratic party that won elections in 2020 under Biden, did little to address key issues of affordability that mattered most to the working- class majority.

Trump won again in the 2024 elections, in large part because of Biden’s blindness on issues of affordability. Biden chose to offer unlimited financial support for Ukraine following the Russian invasion in February 2022; and he committed the nation’s taxpayers to finance unconditional military support for Israel’s relentless bombardment of Palestinians when Hamas broke out of its concentration camp in Gaza on October 7, 2023, killing at least a thousand Israeli civilians and taking hundreds hostage.

As Israel unleashed full-scale military assault on Gaza, the huge casualties that immediately followed turned public opinion against Israel. It compelled South Africa in late December 2023, to launch a case at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) accusing Israel of committing genocide.

By the time Mamdani announced he was running for mayor of New York late in October 2024, massive worldwide demonstrations against Israeli State-terrorism routinely dominated global social media. By September 16, 2025, a report published by the UN Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian Territory, claimed that Israel committed genocide against Palestinians in Gaza. In fact, several human rights organisations explicitly condemned the Israeli State for committing genocide – these include Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, Oxfam, Genocide Watch, as well as B’Tselem (the Israeli Human Rights organisation).

Mamdani’s criticisms of the Israeli State remain grounded in harsh empirical reality; he rejected the charge of anti-semitism leveled against him and is supported by at least 30% of Jews in New York, including organisations like Jewish Voice for Peace.

Along with issues of political and corporate corruption in the city, Palestine and Islamophobia became controversial watchwords of the Mamdani campaign against lacklustre mainstream rivals in the summer primary and in the general elections in November. Noteworthy is Zohran Mamadani’s use of multiple forms of social media (on YouTube, on Instagram) to connect directly with the younger generation in multiethnic languages, working class concerns. These short savvy media messages repeatedly conveyed the image of an uncompromising ally of working families.

Mamdani’s road to victory was built on exemplary focus on what mattered most to millions of New Yorkers: integrity instead of dishonesty, corruption, and complicity in genocide; a working class politics that emphasised respect for the dignity of all working families instead of corporate welfare handouts (tax cuts and subsidies for big businesses); and an affordable city for its multitudes rather than a city for sale to a small clique of billionaires.

MAMDANI’S CROSS-CLASS COALITION

In two insightful articles the historian Adam Tooze identifies the core of Mamdani’s new coalition as belonging to a “middle income band” that stretches from $60,000 to $150,000; while Cuomo did best in the income band that stretches over $150,000 and beyond. Does this mean that Mamdani rode to power on the backs of a middle-class coalition? This is, of course, partly true. However, as the working-class theorist Michael Zweig (The Working Class Majority: America’s Best-Kept Secret, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY) argues, class is best seen not in terms of income or consumption or lifestyle, but in terms of power, defined by the extent of autonomy and authority at the workplace. Income is, of course, associated with class; but it is workplace-power that determines class-belonging.

The middle class of small business owners, foremen and supervisors, managers and professionals, shares some common ground with both the capitalist class and the working class. Although the middle class enjoys relatively greater autonomy and authority at the workplace compared with the working class, its relative power dwindled during the neoliberal decades of austerity and cutbacks. Lower-level managers in big businesses experienced layoffs and downsizing during the 1990s and beyond, even as small business owners in working class neighborhoods lost market share to big businesses.

As capitalist restructuring reshaped lower and higher levels of the educational institution, it also reshaped the lives of teachers in middle and high schools, and of faculty in the City University of New York (CUNY), where the the majority of teaching responsibilities are outsourced to strongly qualified but poorly paid adjunct intellectual workers. All these professional groups – lower-level managers, teachers, adjunct professors, as well as doctors serving in working class neighborhoods, and the majority of nurses – tend to be more closely associated with the working class: most of them have experienced long-term downward social mobility.

Other middle-class groups more closely associated with the capitalist class prospered dramatically – like corporate lawyers, tax accountants, financial professionals – in large part because their work the top 1-2% of the owners and directors of big businesses to make huge fortunes. There is probably no clear answer, as author-activist Barbara Ehrenreich argues, to the question of whether the middle class is an extension of the working class or an elite group more closely aligned with the interests of the capitalist class. (Barbara Ehrenreich (1989) Fear of Falling: The Inner Life of the Middle Class: Pantheon, NY)

The political inclinations of the middle class may or may not be inclined to the Left, or to the Right. Historical circumstances determine the choice. Inequalities in the US distribution of income worsened between 1968 and 2009. If polarisation was moderate at the national level since 2010, it steeply increased in New York City where the earnings of those in the top 3% or 10% saw sharp upward spikes in incomes and wealth, while the rest saw real wage increases that barely kept up with rising costs of living.

The neoliberal austerity decades of the1980s and beyond, thus not only damaged the lives of the working class; it also downgraded the middle class to the status of skilled workers. In New York City, during the Occupy movement, the middle class made its political choice by joining the great class war against big businesses. In 2025, the middle class again made its political choice by strongly supporting Mamdani’s campaign platform that ‘New York is not for sale’ to the billionaires who poured millions into Andrew Cuomo’s campaign even after Cuomo lost the summer primary. The larger point is that the middle class was most certainly not alone in backing Mamdani. It made its choice to combine with the deeper and more powerful working-class currents that swept Mamdani to power.

MAMDANI AND THE LABOUR MOVEMENT

These multiple class currents cannot be contained in the unions that claim to represent the working class. The labour movement is far bigger than the unions that claim to represent the city’s hugely diverse working class. The divisions within unions make the future of American working-class politics so unpredictable!

As early as December 2024, well before the summer primary in June 2025, the United Auto Workers (UAW Region 9A) with its 20,000 members was outstanding in its principled endorsement of Mamdani. The same may be said of the City University of New York (CUNY) and its Professional Staff Congress (PSC-CUNY); as well as of the largest public sector union representing 150,000 city workers, AFSCME District Council 37. But these were still exceptions. The UAW and the New York’s Taxi Workers Alliance deserve special mention because what they ultimately endorsed was Mamdani’s unimpeachable integrity, his deep respect for the dignity of working-class families, so rare among politicians. The UAW’s appreciation for Mamdani’s personal involvement in auto workers’ livelihood struggles was expressed by its director Brandon Mancilla: “He's been front and centre at every single one of our fights, whether it’s in higher education at Columbia or at the Mercedes-Benz first contract rally.”

But Mamdani was also front and centre of the 15-day hunger strike for debt relief waged by New York City’s taxicab drivers in 2021. His participation in that strike earned him the loyalty, affection, and abiding trust of the city’s 50,000 multiethnic taxi workers – Algerian, Bangladeshi, Senegalese and South Asian workers – who make New York a city that never sleeps. As Bhairavi Desai, president of the New York Taxi Workers Alliance explains, “Members witnessed this humble state assembly member insist on being the last in line behind them to be checked by physicians during the hunger strike”. Taxi workers and their families became Mamdani’s campaign guides and foot soldiers, who along with DSA’s volunteers, knocked on millions of doors in solidarity with a new type of city politics. Bhairavi observes that taxi drivers identified completely with Mamdani’s focus on immigrants and workers: “they see Mamdani carrying the working class with him in every step he takes toward power”.

If the UAW lobbied hard for support for Mamdani among other labour unions before the summer primary, these efforts were in vain! Most unions backed the corrupt Cuomo, perhaps in part because Mamdani was a political nonentity before February 2025, polling in the 1-5% range. New York City’s Central Labor Council (NYC-CLC) of the AFL-CIO with its million workers belonging to 300 unions did not endorse Mamdani until he had decisively defeated Andrew Cuomo in June, winning 56% of the votes to become the Democratic party’s candidate in the general elections in November. It was only then that previously neutral unions like the United Federation of Teachers, as well as former Cuomo endorsers like the largest healthcare union in the northeast (SEIU-1199) and SEIU-32BJ (representing doormen and building workers), stepped up to endorse him.

Mamdani had to prove capable of defeating Cuomo with whatever support he could mobilise with his radically different vision for the future of the labour movement. NYC-CLC President Vincent Alvarez seems to have realised Mamdani’s authenticity only at the end of June 2025, when he admitted that “Zohran Mamdani shares the… Labor Movement’s vision for a city where working people have power, dignity, and opportunity…. We look forward to partnering with him to advance a pro-worker agenda and … to fight for policies that protect the right to organise, invest in union jobs, and ensure economic growth doesn’t come at the expense of workers”. For his part, Mamdani accepted the NYC-CLC endorsement, as ‘a profound honor that confers a solemn responsibility to deliver on our shared vision’, and he promised to stand with organised labour and deliver a city everyone can afford.

MAMDANI AND MINORITY GROUPS

One reason for Mamdani’s success was his willingness to listen attentively to voters’ concerns. Many African American and Latinx voters who voted for Trump in the 2024 general elections, voted for Mamdani because the core issues of unaffordability resurfaced strongly despite Trump’s victory. Although Mamdani did less well in predominantly lower-income African American neighborhoods of the city in the June primary, he did far better in the November general elections in those same minority neighborhoods, as his working-class and middle-class volunteers extended their campaign into the city’s lower-income precincts. Younger voters, irrespective of race and gender, turned out in unprecedented numbers to vote for Mamdani.

Mamdani has often been accused of anti-semitism by his opponents because of his criticisms of Israel. Critics of Israel are branded as Hamas supporters. To equate anti-semitism with criticism of Israel is highly questionable. Mamdani denies the charge, and a non-trivial slice of Jewish New Yorkers back him. At least 30% of Jewish New Yorkers voted for Mamdani; and 68% percent of American Jews have negative views of Israel’s current government.

If Americans should not discount the resurgence of anti-semitism in the US, neither should they dismiss Islamophobia. Since the terrorist attacks on Manhattan’s twin towers, Islamophobia became embedded in the nation. Political policing of Muslims became part of the US War on Terror and ‘Black Identity Extremists’, and as part of the effort to undermine the Black Lives Matter Movement. There was no attempt in mainstream media to ask if US foreign policy in Afghanistan and West Asia were connected to international terrorism.

Mahmood Mamdani (the mayor-elect’s world-renowned father who teaches at Columbia University) observed in 2004 that stereotypical media constructions of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ Muslim in American minds, are simplistically associated with support for or criticism of US foreign policy in West Asia and US endorsement of Israeli state terrorism.

As for the anti-Jewish threat in the nation, it comes largely from the right. As journalist Ed Luce (“Don’t blame the left for US antisemitism”, Financial Times, November 4, 2025) observed in the Financial Times, “Trump has built his appeal on licensing every prejudice under the sun. In nativist social media, and especially on Musk’s X, Nazi admiration is no longer in hiding. Now it threatens to enter America’s bloodstream”, as “a constellation of figures – from JD Vance, the US vice-president, to Elon Musk, the world’s richest man – are, wittingly or otherwise, making antisemitism respectable again.”

CAN MAMDANI’S AGENDA SUCCEED?

For young Mamdani, governing a sprawling municipal bureaucracy of 300,000 city workers serving 8.5 million New Yorkers will be a big challenge. He has begun the process of selecting an expert administrative team. Can they implement his progressive agenda of rent freeze, free buses, free childcare, and 200,000 new affordable housing units, all paid for by taxes on billionaires and millionaires?

Mamdani took the bold step of meeting with President Trump in Washington in late November. To everyone’s surprise, the meeting was not a ‘showdown’ between two diametrically opposite personalities, perhaps because both agreed to reaffirm their common affordability agenda on which both won their elections. It is not clear whether Trump will deploy ICE on New York’s streets to pursue his anti-immigrant politics. For the moment, we may want to trust on Mamdani’s resourcefulness.

That still leaves Governor Hochul in Albany, a centrist Democrat, who endorsed Mamdani’s campaign, supports his universal childcare agenda (New Yorkers currently spend $22,500/year on childcare for one child), but remains opposed to increasing taxes by 2% on millionaires. Freezing the rent (2.5 million New Yorkers live in rent-stabilised buildings) can be done without Albany’s assistance. The other parts of his agenda will depend on Mamdani’s relationship with Albany. Free buses will deprive New York’s Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) of over $700 million/year. What alternative sources of revenue will Mamdani’s administration provide to the MTA? Will he able to fund free childcare?

Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBA) cuts federal taxes by $4.5 trillion over the next 10 years, paid for through higher deficits on the one hand; and $1.1 trillion in cuts to Medicaid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) on the other. These Federal funding cuts, however, will not directly impact the $7 billion in annual Federal funding that New York City receives. These Federal funding cuts, however, will impact New York’s State-budget by about $4.5 billion per year in lost federal funding, in large part through Trump’s elimination of Obamacare subsidies for legal resident immigrants. They may thus impact the $19 billion in annual funding that NY State channels to New York City, putting pressure on the city’s budget of $116 billion/year. Mamdani’s new administration will have to demand that the state government in Albany manage OBBBA impacts without implementing spending cuts.

Nathan Gusdorf’s instructive appraisal of the fiscal challenges confronting Mamdani’s administration underlines the importance of resisting the anti-tax movement in New York. “The idea that taxing a handful of billionaires is sufficient to achieve social democracy remains a progressive fantasy”. Trump’s OBBA tax cuts are not only skewed towards the top 1%; it is the top 20% of households who earn over $120,000 annually that will receive 70% of the benefits from OBBA tax cuts (= $3.15 trillion). New York can successfully surmount the fiscal challenges it will confront, because “the state and the city are both in a sound economic position to raise taxes given the stock of upper-middle- and high-income earners”. All of the costs of implementing the mayor-elect’s affordability agenda could be effectively covered by his proposed tax increases, which are designed to raise $10 billion annually.

The future of American politics struggles to be rewritten in the aftermath of Mamdani’s stunning victory. Some of the recent electoral turns may be signs of the future. Katie Wilson, a Democratic Socialist, became Seattle’s new Mayor-elect after campaigning on affordability issues. New Jersey’s new Governor-elect, Mikie Sherrill, also won an affordability campaign as a Democratic party candidate. In Virginia, Abigail Spanberger become Virginia’s new Democrat Governor-elect. If these wins bode well for the Democrats’ immediate future in the midterms, it is unclear whether the party machine can muster the will to radically shift course. After all, neither Obama nor the Clintons endorsed Mamdani. The NY Senator Chuck Schumer did nothing for Mamdani.

Divided by loyalty to the Israel lobby, and committed to oligarchical interests, the party of the Democrats seems unable to see into the future. Alongside this myopia it retains an enormous condescension for subaltern groups. If Mamdani represents a different life and symbol, the party to which he belongs is far from forging a vision adequate to the challenges ahead.

Ganesh Trichur teaches historical sociology and political economy at the City University of New York. The views are personal.

Dhoom Macha Le: How Zohran Mamdani’s NYC Mayoral Victory Challenges Authoritarian Trends

Zohran Mamdani’s victory will have reverberations beyond New York and beyond America

Harish Khare

Updated on: 10 November 2025

OUTLOOK. INDIA

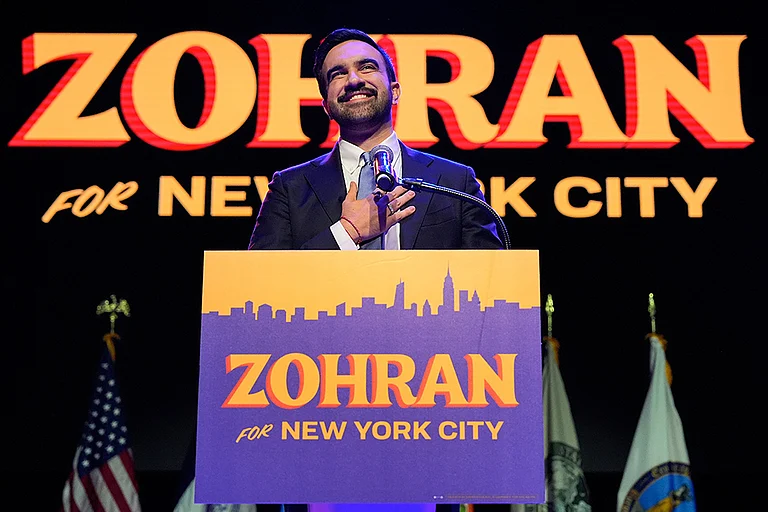

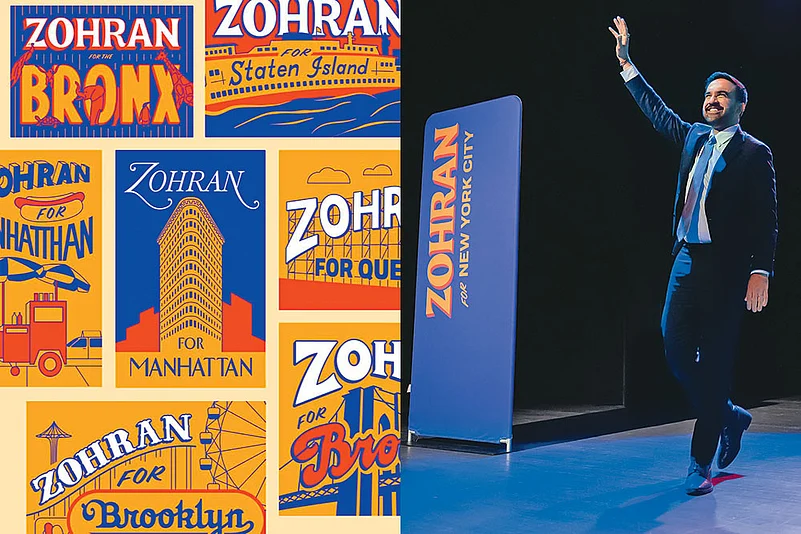

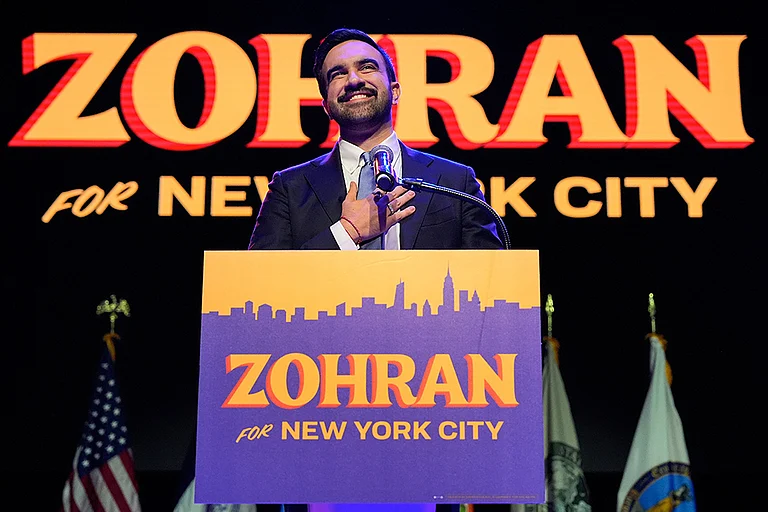

Questioning the Status Quo: (Left) Campaign posters of Zohran Mamdani; (right) Mamdani at an election party in New York

Summary of this article

Zohran Mamdani’s election as NYC mayor marks a major rejection of divisive, Trump-era politics and reaffirms faith in democratic, inclusive ideals.

His victory symbolises a new political movement that challenges entrenched power and prioritizes ordinary citizens over oligarchic interests.

The outcome resonates globally, inspiring democratic voices beyond the US by proving that course correction in a democracy is still possible.

Just when we were being made to believe that the future belongs to autocrats and authoritarian demagogues, there is cheerful news from New York City: democracy has not exhausted its potential for enlightened change and for moral refurbishing.

Democrats and otherwise sober men and women across the world have every reason to be humming Liza Minnelli’s ode to that city:

Start spreading the news,

I’m leaving today,

I want to be a part of it,

New York, New York

Just a little over two decades ago, the city was the site of a horrendous terrorist act; the iconic Twin Towers got gutted as evil men drove two hijacked aeroplanes into them; thousands died; “9/11” changed the way the world thought about its values and beliefs and priorities; warmongers manufactured a narrative that took us away from basic democratic principles; that cataclysmic event set the stage for over-use of military power, state terror, Islamophobia, and the eruption of a very ugly nationalism. Legitimacy and acceptability accrued to any demagogue who could use the pulpit to talk the language of bigotry and hate. Religious fanaticism all over the world found new voices and new adherents and partisans.

Now the same city has elected a 34-year-old man with a Muslim name as its mayor. His rivals sought to make much of his religion and his ethnic background, but the city voters refused to be scared into favouring those who prosper by mongering distrust and divisiveness. Instead, the voters chose to back a man who was offering hope and togetherness.

Zohran Mamdani’s victory has been cheered across the world because it was as much a triumph of a new kind of politics as it is a rebuff to President Donald Trump and his politics of intimidation and invective, at home and abroad. Trump had, needlessly but unsurprisingly, injected himself into the New York mayoral contest by backroom quarterbacking of Mamdani’s rivals, as also by threatening to slash federal funds for the city should this challenger of status quo got elected.

It is necessary to note that both Mamdani and Trump are quintessential products of that great city. A town of hustlers, swindlers, conmen, creative geniuses, ethnic vibrancy; a city that favours men and women of elegance, style, fashion, wit, imagination, optimism, and sheer perseverance. It refuses to be a settled down place; always willing to engage with one more experiment in social arrangements. Both Trump and Mamdani are New Yorkers at the core. On November 4, the city created a new narrative for itself and it will be decoded and deciphered around the world—for inspiration and for replication. Just as Liza Minnelli sang: “If I can make it there, I’ll make it anywhere.”

Indian Reaction To Indian-Origin Mamdani's Win In NYC Somewhat Mixed

Since his second presidential innings began in January, 2025, Trump has relentlessly devalued the idea of American democracy in the eyes of millions and millions of Americans, and, in the process, has sent out an unhappy message to the world that looked upon the US as an ideal democracy, worthy of emulation. The maximalist interpretation that Trump has put on his presidential powers—and has been allowed to get away with it—has given heart to all the “strongmen” across the world who use the paraphernalia of elective democracy to hollow out the very concept of democracy. In the Trumpian theocracy, authority is not to be questioned; ‘obedience must be rendered to the Caesar’. The very idea of dissent has been reduced to a dirty concept.

Now, a Mamdani victory has not only dented the Trump Supremacy, it has also proved that there is nothing inevitable about Trump and Trumpism. A veritable bonfire of the Trumpian vanities has become the most pleasing spectacle. For one shining moment, New York City has reaffirmed its romantic streak and has given hope to millions and millions, way beyond that exotic metropolitan.

Mamdani was wilfully not a part of the establishment; he wormed his way into the affection of the New Yorkers by questioning the status quo, challenging the political priorities, and the governing protocol of an establishment that is firmly in the grip of oligarchs and other power brokers. Mamdani reminded the city’s voters of the harshness of life behind all the glitter and the shimmer of the Manhattan skyline. And then, he promised to make life for the average voter less harsh and less dehumanising. He invoked the curative power of inclusion, without brandishing the animosities of politics of exclusion that has cast a mesmerising spell on so many Americans. He invited opposition and hostility from every established site of traditional power.

The Mamdani victory will have reverberations beyond New York and beyond America. Because this man, with a very un-American name, has shown how a politician can rekindle a society’s conscience and how he or she can summon the faithful and the hopeful to defiance and resistance to callous authority, and, can enthuse a community to reach out to its inner resources and resilience to forge a higher collective nobility. A seductive moment in history.

The world will watch with attention how Mamdani will defuse and defang the entrenched interests in America’s greatest city and how he will cope with militant non-cooperation, even hostility, from the Trump White House. And, as the older Cuomo, Mario, once remarked that while “you campaign in poetry, you govern in prose”. Governance is a tricky affair; it requires competence, passion, commitment, and conviction to exhort citizens and followers to rise above personal and petty interests. Aspirant political leaders across the world would very much want a Mamdani City Hall to set an example as to how to govern in prose without losing the imagination of a poet.

It is not easy to pigeonhole Mamdani and his fellow-travellers in any recognised political category, but they do constitute a “new” urge and a “new” insistence that the operating principles of governance must be aligned with the needs and requirements and hopes of a majority, rather than being the handmaiden of the dozen-odd billionaires and political honchos.

The progressive, liberal, and other democratic souls around the world would observe how creative and adept Mamdani turns out in using the mandate of the crowds through the existing political institutions; how he would avoid the pitfalls of impatience and righteousness; and, how he would not let his rivals’ viciousness define him. A Mamdani mayoralty in the world’s most global city has a tantalising cachet to it. From the dark days of “9/11” New York moved back, on “11/4” to its old zeitgeist. All is not lost.

Many in India would feel entitled to think of Mamdani’s triumph as a reaffirmation of the intrinsic validity of our own democratic values. That his mother is an Indian, that he would quote Jawaharlal Nehru in his victory oration, that he did not shy away from his Muslim identity are enormously satisfying to our liberal and republican votaries. More than the elevation of a Rishi Sunak as the prime minister of England, a Zohan Mamdani as the Mayor of New York somehow is a pleasing development. In this age of inter-connectedness, a Mamdani victory in New York will give hope to the dispirited democrats call over the world. India will not remain untouched. Some would hope for a similar de-contamination. Never underestimate a democracy’s potential for undertaking course-correction and other similar miracles.

(Views expressed are personal)